Juan Domínguez de Mendoza

Juan Domínguez de Mendoza (born 1631) was a Spanish soldier who played an important role in suppressing the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and who made two major expeditions from New Mexico into Texas.

Juan Domínguez de Mendoza | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1631 |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Occupation | Soldier, Explorer, Politician |

| Known for | Texas explorations |

Early career

Juan Domínguez de Mendoza was born in 1631.[1] He was a member of the wealthiest family in New Mexico.[2] He had, at least, two siblings (between them, the governor of New Mexico Tomé Dominguez de Mendoza[3]). At the age of twelve he went to New Mexico, and he was to accompany several expeditions into what is now Texas.[4]

He was a member of the Diego de Guadalajara expedition of 1654 from Santa Fe to what is now San Angelo, Texas, where the three main tributaries of the Concho River converge. Domínguez rose in rank to lieutenant general and was appointed Maestro de Campo in New Mexico - second in command to the Governor.[1] He was an able administrator, and by the time of the Pueblo Revolt in 1680 was one of the most experienced and capable of the New Mexico militia leaders. When the Pueblo Revolt broke out, Domínguez advanced north from Isleta Pueblo to Cochiti, to the southwest of Santa Fe. However, he was then forced to retreat to El Paso del Norte (now Cuidad Juarez).[2] Later he was criticized for not being sufficiently aggressive in his action against the Pueblos.[2]

Second Texas expedition

In 1680, a major uprising of Native American tribes later termed as the Pueblo Revolt, completely uprooted the vast majority of the Spanish colonies in the New Mexico region. The Europeans were forced to retreat to the site of present day El Paso, Texas where they were reinforced by a large supply of munitions and manpower. Rather than risking a full scale counter attack against the Natives, New Mexican governor, Antonio de Otermin, decided to establish a fort and refuge camp at the Paso del Norte with the intent to organize a stronger military campaign at a later time.

Between 1681 and 1683, Governor Otermin had launched several unsuccessful attacks against the Native American forces that still occupied New Mexico. But by the end of the summer of 1683, Otermin’s ill health and military failures had led the Spanish government to appoint a successor.

On August 28, 1683, Jironza Petriz de Cruzate took command of the New Mexican governorship. Stepping into a quagmire mess, Cruzate faced the difficult challenge of having to re-conquer New Mexico and to prevent a social upheaval in the newer settlements along the Rio Grande. The Spanish colonists either wanted their old homes back, or for new ones to be found.

With winter rapidly approaching, Cruzate was understandably overwhelmed during the early autumn months of 1683. But on October 20, a potential lifeline came riding into El Paso.

A delegation of the Jumano tribe, a culture of Native Americans that had been close allies with the Spaniards since the 1520s, arrived in El Paso. The head leader of the delegation was a man named Juan Sabeata who was an ardent supporter of the Catholic faith and well versed in several languages which included: Spanish, Castilian (a form of Spanish that was frequently spoken in high society), and numerous Native languages from all across present day Texas.

Juan Sabeata requested an audience with Governor Cruzate to present aid to the current situation that the Spanish colonists were currently facing. In exchange for a permanent mission to be established with the Jumanoes near the La Junta de los Rios region (present day Presidio, Texas), Sabeata agreed to personally guide a Spanish expedition into the eastern interior of the Jumano homelands where he stated the Spaniards could find immeasurable amounts of aid from the smaller tribes of Natives in establishing a new settlement.

To add further incentives, Sabeata related a number of divine experiences that he stated he had personally witnessed from God while waging war against the encroaching Apache tribe. In one such instance, Sabeata stated that the Jumanoes were on the verge of losing a fiercely contested battle against the Apaches when a cross appeared in the skies above the battlefield, took a physical form, and dropped from the clouds directly into his hands. With the cross held high, Sabeata claimed, that he led the Jumanoes to a glorious victory that day. Later, he claimed that a multi-colored cross had appeared above La Junta de los Ríos, at the junction of the Rio Conchos and Rio Grande near modern-day Presidio, Texas. (See La Junta Indians) He also talked of wooden houses floating on the sea, which the Spanish took to refer to French ships. Three friars left at once for La Junta, where they started missionary work.[5]

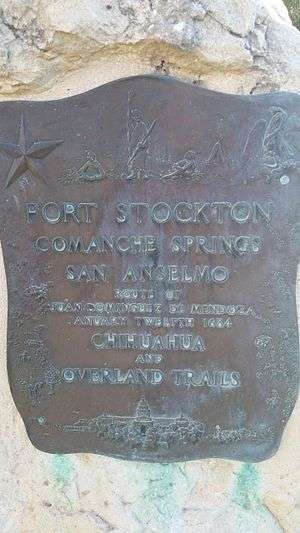

Inspired by Sabeata’s stories, and with a sudden sense of possibly adding an entirely new kingdom to Spain’s domain, Governor Domingo Jironza Petriz de Cruzate agreed to establish the mission the Jumanoes desired and to organize a major exploration of the eastern Jumano homelands. On November 29, 1683, Governor Cruzate appointed Juan Domínguez de Mendoza as the head commander of what would become known as the Mendoza-López Expedition of 1683-84.[1]

Mendoza was given a long list of expectations and duties that he was to make certain were abided by and accomplished at all times. These requirements included: 1) Making sure that the priests who were to accompany him were treated with respect, politeness, and good courtesy by all the members (Natives and Spaniards) of the expedition. 2) To accurately record, in writing, the amount of leagues traveled from camp to camp, the route taken, the natural resources of the wilderness encountered, and any trails he was guided upon. 3) To make certain that, at every camp or village, the Spaniards were to be completely separated from the main abodes of the Native people and to publicly punish any Spaniard who was caught fraternizing with local Native women or bartering with Native craftsmen. 4) He was to reconnoiter the Rio de los Nueces (present day Concho River in San Angelo, Texas) and to both document and bring back examples of the natural amenities that could be found there.[2]

The expedition, often called the Mendoza Expedition, set off from El Paso on 15 December 1683, going down the Rio Grande to La Junta. Fray Antonio de Acevedo was left there in charge of new missions. The rest of the expedition, joined by many Indians, followed Indian trails north to the Pecos River, then followed the Concho River downstream to its junction with the Colorado River. They spent six weeks on what Domínguez called the "glorious San Clemente" river, building a fort, probably near the location of present-day Ballinger, Texas as defense against Apaches and hunting buffalo for hides and food. They fed and baptized many of the friendly local people who visited their camp.[1]

Dominguez de Mendoza and the Jumano leader, Juan Sabeata, clashed early in the expedition. Sabeata, Dominguez said, was untruthful and spread false rumors of hostile Apaches to bring the expedition to a halt.[6] Sabeata apparently believed that the Spaniards were more interested in hunting buffalo than fighting Apache. Sabeata abandoned the expedition as did most of the Indians. A grand council of Indians envisioned by the Spanish never took place and the Spaniards returned to El Paso having collected 5,000 valuable buffalo hides.[7]

Later career

On returning to La Junta de los Ríos, Domínguez took possession of the north bank of the Rio Grande in the name of Spain. Domínguez and López returned to El Paso, and then went on to Mexico City in 1685, where they made a strong case for sending soldiers and missionaries to the Jumano country.[2] Domínguez and López were initially optimistic about the potential for setting up missions among the Jumanos. However, Governor Jironza was unable to help since his forces were tied up combating local insurrections by the Suma and the Manso Indians. The incursion into eastern Texas by Frenchman René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle in 1685 caused another distraction, so there was no immediate follow-up to Dominguez de Mendoza's expedition.[1]

References

- Citations

- Weddle 2012.

- Chipman & Joseph 2010, p. 64.

- Simmons, Marc & Esquibel, José 2008.

- Kessel & Wooster 2005, p. 116.

- Folsom 2008, p. 73-74.

- Mapp 2011, p. 50.

- Bolton 1917, p. 338-343.

- Sources

- Bolton, Herbert Eugene (1917). Spanish Exploration in the Southwest, 1541-1706. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chipman, Donald E.; Joseph, Harriett Denise (2010-01-15). Spanish Texas, 1519-1821. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72180-7. Retrieved 2012-07-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Simmons, Marc; Esquibel, José (2012). Juan Domínguez de Mendoza: Soldier and Frontiersman of the Spanish Southwest, 1627-1696. University of New Mexico Press. Retrieved 2012. Check date values in:

|accessdate=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - Chipman, Donald E.; Joseph, Harriett Denise (2010-01-15). Spanish Texas, 1519-1821. University of Texas Press. ISBN 978-0-292-72180-7. Retrieved 2012-07-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Folsom, Bradley (2008). Spanish La Junta de Los Rios: The Institutional Hispanicization of an Indian Community Along New Spain's Northern Frontier, 1535--1821. ProQuest. ISBN 978-1-109-09348-3. Retrieved 2012-07-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kessel, William B.; Wooster, Robert (2005-03-01). "Domínguez de Mendoza, Juan". Encyclopedia Of Native American Wars And Warfare. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8160-3337-9. Retrieved 2012-07-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mapp, Paul W. (2011-02-01). The Elusive West and the Contest for Empire, 1713-1763. UNC Press Books. ISBN 978-0-8078-3395-7. Retrieved 2012-07-22.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Weddle, Robert S. (2012). "DOMINGUEZ DE MENDOZA, JUAN". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved July 22, 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Further reading

- Mendoza, Juan Domínguez de (2002-07-01). The diary of Juan Domínguez de Mendoza's expedition into Texas (1683-1684): a critical edition of the Spanish text with facsimile reproductions. William P. Clements Center for Southwest Studies, Southern Methodist University. p. 259. ISBN 978-1-929531-05-9. Retrieved 2012-07-22.

- Scholes, France V.; Simmons, Marc; Esquibel, José Antonio (2012-05-15). Juan Domínguez de Mendoza: Soldier and Frontiersman of the Spanish Southwest, 1627-1693. University of New Mexico Press. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-8263-5115-9. Retrieved 2012-07-22.