Texas blackland prairies

The Texas Blackland Prairies are a temperate grassland ecoregion located in Texas that runs roughly 300 miles (480 km) from the Red River in North Texas to San Antonio in the south. The prairie was named after its rich, dark soil.[3]

| Texas Blackland Prairies | |

|---|---|

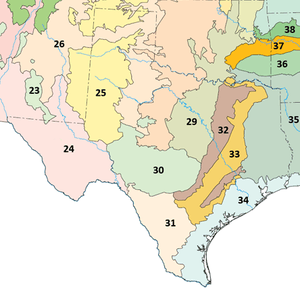

Texas blackland prairies (area 32 on the map) | |

| Ecology | |

| Realm | Nearctic |

| Biome | Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands |

| Borders | East Central Texas forests (area 33 on the map)[1], Edwards Plateau (area 30 on the map)[1] and Cross Timbers (area 29 on the map)[1] |

| Bird species | 216[2] |

| Mammal species | 61[2] |

| Geography | |

| Area | 50,300 km2 (19,400 sq mi) |

| Country | United States |

| State | Texas |

| Conservation | |

| Habitat loss | 76.458%[2] |

| Protected | 0.64%[2] |

Setting

The Texas Blackland Prairies ecoregion covers an area of 50,300 km2 (19,400 sq mi), consisting of a main belt of 43,000 km2 (17,000 sq mi) and two islands of tallgrass prairie grasslands southeast of the main Blackland Prairie belt; both the main belt and the islands extend northeast/southwest.

The main belt consists of oaklands and savannas and runs from just south of the Red River on the Texas-Oklahoma border through the Dallas–Fort Worth metropolitan area and into southwestern Texas. The central forest-grasslands transition lies to the north and northwest, and the Edwards Plateau savanna and the Tamaulipan mezquital to the southwest.

The larger of the two islands is the Fayette Prairie, encompassing 17,000 km2 (6,600 sq mi), and the smaller is the San Antonio Prairie with an area of 7,000 km2 (2,700 sq mi). The two islands are separated from the main belt by the oak woodlands of the East Central Texas forests, which surround the islands on all sides but the northeast, where the Fayette Prairie meets the East Texas Piney Woods.

Formation

This area was shaped by frequent wildfires and visits by plains bison. Large fires ignited by lightning frequently swept the area, clearing shrubs and stimulating forbs and grasses. Large herds of bison also grazed on the grasses, and they trampled and fertilized the soil, stimulating the growth of the tallgrass ecosystem.[4] Hunter-gatherers contributed to the formation and expansion of the prairie through controlled burns to make more land suitable for hunting bison and other game. Hunter-gatherers continually inhabited the prairie since pre-Clovis times over 15,000 years ago. In historic times, they included the Wichita, Waco, Tonkawa, and Comanche, each of whom were gradually replaced by settled agrarian society. The advent of large-scale irrigated farming and ranching in the area ended the expansionary period in the prairie's formation and quickly led to widespread habitat loss.

Conservation

Because of the soil and climate, this ecoregion is ideally suited to crop agriculture. This has led to most of the Blackland Prairie ecosystem being converted to crop production, leaving less than one percent remaining (and some groups estimate less than 0.5% to less than 0.1% remaining) and making the tallgrass the most-endangered large ecosystem in North America. Small remnants are conserved at sites such as The Nature Conservancy's 800-acre Clymer Meadow Preserve near Celeste, TX.

Ecology

Important prairie plants included little bluestem, yellow indiangrass, big bluestem, tall dropseed, and a variety of wildflowers including gayfeathers, asters, Maximilian sunflower, wild indigos and compass plant. The fauna of the Blackland Prairies includes foxes, frogs, lizards, rattlesnakes, opossums, coyotes, white-tailed deer, and striped skunks. The prairie was formerly home to animals such as American bison, wolves, and jaguars before overhunting and the destruction of most tallgrass ecosystems.

The soil of the Blackland Prairies, from which the "blackland" get its name, contains black or deep dark-gray, alkaline clay which is further blackened by char from wildfires and controlled burns. "Black gumbo" and "black velvet" are local names for this soil. In dry weather, deep cracks form in the clay, which can cause serious damage to buildings and infrastructure. Soil management problems also include water erosion, cotton root rot, soil tilth, and brush control.[5]

Texas blackland prairies gallery

%2C_Washington_County%2C_Texas%2C_USA_(30_March_2012).jpg) Ranchland in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas with Texas bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), Washington County, Texas, USA (30 March 2012).

Ranchland in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas with Texas bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis), Washington County, Texas, USA (30 March 2012)..jpg) Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site, Washington County, Texas, USA (30 March 2012).

Washington-on-the-Brazos State Historic Site, Washington County, Texas, USA (30 March 2012)..jpg) Riparian zone of East Mill Creek in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas, Washington County, Texas, USA (26 March 2016).

Riparian zone of East Mill Creek in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas, Washington County, Texas, USA (26 March 2016)._in_the_Blackland_Prairie_eco-region._Highway_532_east_of_Gonzalez%2C_Gonzalez_County%2C_Texas%2C_USA_(19_April_2014).jpg) Texas bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis) in the Blackland Prairie eco-region, Highway 532 east of Gonzales, Gonzales County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014).

Texas bluebonnets (Lupinus texensis) in the Blackland Prairie eco-region, Highway 532 east of Gonzales, Gonzales County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014)..jpg) Ranch and pastureland with wildflowers in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas. County Road 268, Lavaca County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014).

Ranch and pastureland with wildflowers in the Blackland Prairie eco-region of Texas. County Road 268, Lavaca County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014)._on_ranchland_in_the_Blackland_Prairie_eco-region._County_Road_269%2C_Lavaca_County%2C_Texas%2C_USA_(19_April_2014).jpg) Fox Glove (Penstemon cobaea) on ranchland in the Blackland Prairie eco-region. County Road 269, Lavaca County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014).

Fox Glove (Penstemon cobaea) on ranchland in the Blackland Prairie eco-region. County Road 269, Lavaca County, Texas, USA (19 April 2014).

References

- "Ecoregions of Texas" (PDF). U.S. EPA. Retrieved 2016-02-06.

- Hoekstra, J. M.; Molnar, J. L.; Jennings, M.; Revenga, C.; Spalding, M. D.; Boucher, T. M.; Robertson, J. C.; Heibel, T. J.; Ellison, K. (2010). Molnar, J. L. (ed.). The Atlas of Global Conservation: Changes, Challenges, and Opportunities to Make a Difference. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26256-0.

- "Blackland Prairies". Invasives 101. Texas Invasives. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- "Post Oak Savannah and Blackland Prairie Wildlife Management: Historical Perspective". Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Retrieved 2008-08-15.

- "Soils of Texas". Texas Almanac. Texas Historical Society. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- Ricketts, Taylor H., Eric Dinerstein, David M. Olson, Colby J. Loucks, et al. (1999). Terrestrial Ecoregions of North America: a Conservation Assessment. Island Press, Washington DC.

External links

- Native Prairies Association of Texas (NPAT)

- NPAT protected prairies

- The Nature Conservancy (TNC)

- Texas Parks and Wildlife

- "Texas blackland prairie". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Connemara Conservancy

- Soil Physics at Oklahoma State

- Weeds of the Blackland Prairie

- Prairie Time: A Blackland Portrait

- Texas counties map showing the ecoregion

- Weeds of the Blackland Prairie