Gonzales County, Texas

Gonzales County is a county in the U.S. state of Texas. As of the 2010 census, its population was 19,807.[1] The county is named for its county seat, the city of Gonzales.[2] The county was created in 1836 and organized the following year.[3][4] As of August 2020, under strict budgetary limitations, the County of Gonzales government-body is unique in that it claims to have no commercial paper, regarding it as "the absence of any county debt."[5]

Gonzales County | |

|---|---|

| |

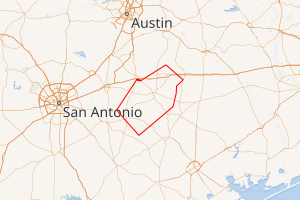

Location within the U.S. state of Texas | |

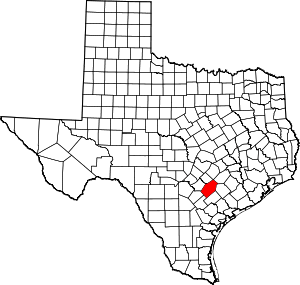

Texas's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 29°27′N 97°29′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | 1837 |

| Named for | City of Gonzales |

| Seat | Gonzales |

| Largest city | Gonzales |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,070 sq mi (2,800 km2) |

| • Land | 1,067 sq mi (2,760 km2) |

| • Water | 3.2 sq mi (8 km2) 0.3%% |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 19,807 |

| • Density | 19/sq mi (7/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| Congressional districts | 27th, 34th |

| Website | www |

According to the census, all areas county-wide had $188,099,000 in total annual payroll (2016), $550,118,900 (±39,442,212; 2018) in aggregate annual income, and $238,574,000 in total annual retail sales (2012). In 2018, the census valued all real estate in the county at an aggregate $795,242,300 (±74,643,103); with an aggregate $29,058,000 of real estate being listed for sale and $173,100 listed for rent. In the same year, approximately, the top 5% of households made an average of $361,318; the top 20% averaged at $188,699; the fourth quintile at $79,601; the third quintile (median income) at $53,317; the second quintile at $31,238; and the lowest at $13,339.[6]

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 1,070 square miles (2,800 km2), of which 1,067 square miles (2,760 km2) is land and 3.2 square miles (8.3 km2) (0.3%) is water.[7]

Major highways

.svg.png)

Adjacent counties

- Fayette County (northeast)

- Lavaca County (east)

- Dewitt County (southeast)

- Karnes County (southwest)

- Wilson County (southwest)

- Guadalupe County (west)

- Caldwell County (northwest)

History

- Paleo-Indians Hunter-gatherers were here thousands of years ago; the later Coahuiltecan, Tonkawa, and Karankawa migrated into the area in the 14th century, but lost much of their population by the 18th century due to new infectious diseases contracted by contact with European explorers. The historic Comanche and Waco tribes later migrated into the area and competed most with European American settlers of the nineteenth century.[8]

- 1519–1685 Hernando Cortez and Alonso Álvarez de Pineda claim Texas for Spain.

- 1685–1690 France plants its flag on Texas soil, but departs after only five years.[9]

- 1821 Mexico won its independence from Spain. Citizens of the United States began to settle in Texas and were granted Mexican citizenship.

- 1825

- Green DeWitt's petition for a land grant to establish a colony in Texas is approved by the Mexican government.

- Gonzales is established and named for Rafael Gonzales, governor of Coahuila y Tejas.

- 1828 When Jean Louis Berlandier visits, he finds settler cabins, a fort-like barricade, agriculture and livestock, as well as nearby villages of Tonkawa and Karankawa.

- 1829, September 15 – Mexican President Vicente Ramon Guerrero, a former slave of Spanish, African and Native American descent, emancipates all slaves within the Republic of Mexico:[10][11]

1st – Slavery is abolished in Mexico.

- 2nd – Consequently, those who have been until now considered slaves are free.

- 3rd – When the circumstances of the treasury may permit, the owners of the slaves will be indemnified in the mode that the laws may provide. And in order that every part of this decree may be fully complied with, let it be printed, published, and circulated.

- Given at the Federal Palace of Mexico, the 15th of September, 1829.

- Vicente Guerrero To José María Bocanegra

- 1831 The Coahuila y Tejas government sends a six-pound cannon to Gonzales for settlers' protection against Indian raids.

- 1835

- The colony sends delegates to conventions (1832–1835) to discuss disagreements with Mexico.

- September – The Mexican government views the conventions as treason. Troops are sent to Gonzales to retrieve the cannon.

- October 2 – The Battle of Gonzales becomes the first shots fired in the Texas Revolution. The colonists put up armed resistance, with the cannon pointed at the Mexican troops, and above it a banner proclaiming, "Come and take it". Commemoration of the event becomes the annual "Come and Take It Festival".[12][13]

- October 13 – December 9 – Siege of Bexar becomes the first major campaign of the Texas Revolution.

- October 2 – The Battle of Gonzales becomes the first shots fired in the Texas Revolution. The colonists put up armed resistance, with the cannon pointed at the Mexican troops, and above it a banner proclaiming, "Come and take it". Commemoration of the event becomes the annual "Come and Take It Festival".[12][13]

- September – The Mexican government views the conventions as treason. Troops are sent to Gonzales to retrieve the cannon.

- 1836

- Gonzales County is established.

- February 23 – Alamo messenger Launcelot Smithers carries to the people of Gonzales, the Colonel William Barret Travis letter stating the enemy is in sight and requesting men and provisions.

- February 24 – Captain Albert Martin delivers to Smithers in Gonzales the infamous "Victory or Death" Travis letter addressed "To the People of Texas and All Americans in the World" stating the direness of the situation. Smithers then takes the letter to San Felipe,[14] site of the provisional Texas government.

- February 27 – The Gonzales Alamo Relief Force of 32 men, led by Lieutenant George C. Kimble, depart to join the 130 fighters already at the Alamo.[15]

- March 1 – The Gonzales "Immortal 32" make their way inside the Alamo.

- March 2 – Texas Declaration of Independence from Mexico establishes the Republic of Texas.

- March 6 – The Alamo falls.

- March 13–14 – Susanna Dickinson, the widow of the Alamo defender Almaron Dickinson, arrives in Gonzales with her daughter Angelina and Colonel Travis' slave Joe. Upon hearing the news of the Alamo, Sam Houston orders the town of Gonzales torched to the ground, and establishes his headquarters under a county oak tree.[16][17]

- April 21–22 – Battle of San Jacinto, Antonio López de Santa Anna captured.

- May 14 – Santa Anna signs the Treaties of Velasco.

- April 21–22 – Battle of San Jacinto, Antonio López de Santa Anna captured.

- March 13–14 – Susanna Dickinson, the widow of the Alamo defender Almaron Dickinson, arrives in Gonzales with her daughter Angelina and Colonel Travis' slave Joe. Upon hearing the news of the Alamo, Sam Houston orders the town of Gonzales torched to the ground, and establishes his headquarters under a county oak tree.[16][17]

- March 6 – The Alamo falls.

- March 2 – Texas Declaration of Independence from Mexico establishes the Republic of Texas.

- March 1 – The Gonzales "Immortal 32" make their way inside the Alamo.

- February 27 – The Gonzales Alamo Relief Force of 32 men, led by Lieutenant George C. Kimble, depart to join the 130 fighters already at the Alamo.[15]

- February 24 – Captain Albert Martin delivers to Smithers in Gonzales the infamous "Victory or Death" Travis letter addressed "To the People of Texas and All Americans in the World" stating the direness of the situation. Smithers then takes the letter to San Felipe,[14] site of the provisional Texas government.

- February 23 – Alamo messenger Launcelot Smithers carries to the people of Gonzales, the Colonel William Barret Travis letter stating the enemy is in sight and requesting men and provisions.

- 1838 Gonzales men found the town of Walnut Springs (later Seguin) in the northwest section of the county.

- 1840 Gonzales men join the Battle of Plum Creek against Buffalo Hump and his Comanches.

- 1845, December 29 – Texas Annexation by the United States

- 1846, May 13 – The United States Congress officially declares war on Mexico.

- 1848, February 2 – Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo officially ends the Mexican–American War.

- 1850 Gonzales College is founded by slave-owning planters, and is the first institution in Texas to confer A.B. degrees on women.

- 1853 The Gonzales Inquirer begins publication.[18]

- 1860 County population is 8,059, including 3,168 slaves.

- 1861

- County votes 802–80 in favor of secession from the Union.

- February 1 – Texas secedes from the Union

- March 2 – Texas joins the Confederate States of America

- February 1 – Texas secedes from the Union

- 1863

- January 1 – Abraham Loncoln announces the Emancipation Proclamation, declaring all slaves in Confederate held territory to be free.[19]

- 1865

- The main Confederate armies east of the Mississippi surrender in April, virtually ending the American Civil War. The Confederate military forces in Texas follow suit in May, as the units either surrender or simply disband. The soldiers return to their homes.

- June 19 – Major General Gordon Granger arrives in Galveston to enforce the emancipation of all slaves. It is the first time African Americans in Texas know of the Emancipation. The date becomes celebrated annually in Texas as Juneteenth, and later as an official state holiday known as Emancipation Day.[22]

- December 6 – The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits slavery.

- June 19 – Major General Gordon Granger arrives in Galveston to enforce the emancipation of all slaves. It is the first time African Americans in Texas know of the Emancipation. The date becomes celebrated annually in Texas as Juneteenth, and later as an official state holiday known as Emancipation Day.[22]

- 1866–1876 The Sutton–Taylor feud, which involves outlaw John Wesley Hardin, and is reportedly the bloodiest and longest in Texas history. Hardin's men are known to have stayed in the community of Pilgrim.[23][24]

- 1870, March 30 – The United States Congress readmits Texas into the Union.

- 1874 The Galveston, Harrisburg and San Antonio Railway is built through the eastern and northern part of the county.

- 1877 The Texas and New Orleans Railway comes to the county.

- 1881 The Gonzales Branch Railroad is chartered.[25]

- 1885 The San Antonio and Aransas Pass Railway runs through the county.

- 1894 John Wesley Hardin is released from prison and returns to Gonzales, where he passes the bar exam and practices law.

- 1898 Twenty-three county men serve, with two casualties, during the Spanish–American War. Three serve with the Rough Riders.

- 1905 The Southern Pacific line bypasses the community of Rancho.

- World War I – 1,106 men from the county serve.

- 1935 – Governor James Allred dedicates a monument in the community of Cost, commemorating the first shot of the Texas Revolution. Sculptress is Waldine A. Tauch.[26][27]

- 1936 Palmetto State Park opens to the public.[28]

- 1939 The Gonzales Warm Springs Foundation opens for the treatment of polio.[29]

- World War II – 3,000 men from Gonzales County serve, with 79 casualties.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 1,492 | — | |

| 1860 | 8,059 | 440.1% | |

| 1870 | 8,951 | 11.1% | |

| 1880 | 14,840 | 65.8% | |

| 1890 | 18,016 | 21.4% | |

| 1900 | 28,882 | 60.3% | |

| 1910 | 28,055 | −2.9% | |

| 1920 | 28,438 | 1.4% | |

| 1930 | 28,337 | −0.4% | |

| 1940 | 26,075 | −8.0% | |

| 1950 | 21,164 | −18.8% | |

| 1960 | 17,845 | −15.7% | |

| 1970 | 16,375 | −8.2% | |

| 1980 | 16,883 | 3.1% | |

| 1990 | 17,205 | 1.9% | |

| 2000 | 18,628 | 8.3% | |

| 2010 | 19,807 | 6.3% | |

| Est. 2019 | 20,837 | [30] | 5.2% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] 1850–2010[32] 2010–2014[1] | |||

As of the census[33] of 2000, there were 18,628 people, 6,782 households, and 4,876 families residing in the county. The population density was 17 people per square mile (7/km²). There were 8,194 housing units at an average density of 8 per square mile (3/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 72.25% White, 8.39% Black or African American, 0.53% Native American, 0.26% Asian, 0.09% Pacific Islander, 16.48% from other races, and 2.01% from two or more races. 39.62% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 6,782 households out of which 34.20% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 54.00% were married couples living together, 12.30% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.10% were non-families. 25.20% of all households were made up of individuals and 14.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.69 and the average family size was 3.21.

In the county, the population was spread out with 28.00% under the age of 18, 8.70% from 18 to 24, 25.70% from 25 to 44, 20.90% from 45 to 64, and 16.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females there were 98.40 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.00 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $28,368, and the median income for a family was $35,218. Males had a median income of $23,439 versus $17,027 for females. The per capita income for the county was $14,269. About 13.80% of families and 18.60% of the population were below the poverty line, including 23.60% of those under age 18 and 19.40% of those age 65 or over.

Communities

Cities

- Gonzales (county seat)

- Nixon (small part in Wilson County)

- Smiley

- Waelder

Unincorporated communities

Ghost towns

Politics

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 72.3% 4,587 | 24.7% 1,571 | 3.0% 191 |

| 2012 | 69.6% 4,216 | 29.3% 1,777 | 1.1% 64 |

| 2008 | 64.8% 4,076 | 34.5% 2,167 | 0.7% 44 |

| 2004 | 71.3% 4,291 | 28.4% 1,709 | 0.4% 22 |

| 2000 | 67.4% 4,092 | 30.9% 1,877 | 1.7% 100 |

| 1996 | 51.9% 2,687 | 40.7% 2,110 | 7.4% 385 |

| 1992 | 45.0% 2,502 | 36.1% 2,006 | 18.9% 1,049 |

| 1988 | 50.4% 2,983 | 49.0% 2,897 | 0.6% 36 |

| 1984 | 64.2% 3,962 | 35.6% 2,196 | 0.2% 14 |

| 1980 | 49.5% 2,931 | 48.9% 2,896 | 1.6% 95 |

| 1976 | 35.6% 1,789 | 64.1% 3,219 | 0.4% 18 |

| 1972 | 69.8% 2,707 | 30.0% 1,164 | 0.1% 5 |

| 1968 | 33.6% 1,476 | 44.0% 1,930 | 22.4% 983 |

| 1964 | 26.2% 1,190 | 73.7% 3,348 | 0.2% 7 |

| 1960 | 36.2% 1,554 | 63.6% 2,730 | 0.2% 7 |

| 1956 | 43.8% 1,767 | 56.0% 2,260 | 0.3% 10 |

| 1952 | 46.7% 2,249 | 53.2% 2,563 | 0.1% 3 |

| 1948 | 18.5% 666 | 72.6% 2,612 | 8.9% 321 |

| 1944 | 21.1% 841 | 70.3% 2,804 | 8.6% 342 |

| 1940 | 19.4% 722 | 80.6% 3,008 | 0.1% 2 |

| 1936 | 11.6% 352 | 88.2% 2,674 | 0.2% 7 |

| 1932 | 9.0% 337 | 90.8% 3,384 | 0.2% 7 |

| 1928 | 45.7% 1,112 | 54.3% 1,319 | |

| 1924 | 14.1% 463 | 76.0% 2,499 | 10.0% 328 |

| 1920 | 30.1% 748 | 52.3% 1,299 | 17.6% 437 |

| 1916 | 27.3% 649 | 70.4% 1,675 | 2.4% 57 |

| 1912 | 17.4% 318 | 72.6% 1,327 | 10.0% 182 |

See also

References

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved December 16, 2013.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on 2011-05-31. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- Dorcas Huff Baumgartner; Genevieve B. Vollentine (June 15, 2010). "Gonzales County". Handbook of Texas Online. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- "Gonzales County". Texas Almanac. Texas State Historical Association. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- Sjoberg, Brooke. "Pay a concern at meeting". The Gonzales Inquirer. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "Gonzales County, Texas". Census Data. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- B., BAUMGARTNER, DORCAS HUFF and VOLLENTINE, GENEVIEVE (2010-06-15). "GONZALES COUNTY". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "A Texas Scrapbook: San Antonio's Military Plaza". www.lsjunction.com. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "The Magnificent Life of Vicente Ramon Guerrero", CWO

- "Chieftains of Mexican Independence" Archived 2007-08-16 at the Wayback Machine, Texas A&M University

- Gonzales C of C Archived 2010-09-24 at the Wayback Machine

- RICKS, LINDLEY, THOMAS (2010-06-15). "GONZALES "COME AND TAKE IT" CANNON". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- CHRISTOPHER, JACKSON, CHARLES (2010-06-15). "SAN FELIPE DE AUSTIN, TX". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Wayback Machine: The DeWitt Colony Alamo Defenders". Internet Archive. 1998-12-02. Archived from the original on 1998-12-02. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Sam Houston Oak, Texas historic tree near Gonzales". www.texasescapes.com. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- Texas Historical Markers, Sam Houston Oak Archived 2011-09-28 at the Wayback Machine

- "The Gonzales Inquirer". www.gonzalesinquirer.com. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Featured Documents: The Emancipation Proclamation". National Archives. 2015-10-06. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- B., MCCRAIN, JAMES (2010-06-12). "FORT WAUL". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- YouTube The Forgotten Fort: Fort Waul, Southern Legacy Films

- Cinnamon Hearts Juneteenth Archived 2010-03-01 at the Wayback Machine

- L., SONNICHSEN, C. (2010-06-15). "SUTTON-TAYLOR FEUD". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "The Sutton-Taylor Feud of DeWitt County, Texas – Legends of America". www.legendsofamerica.com. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- BECK, YOUNG, NANCY (2010-06-15). "GONZALES BRANCH RAILROAD". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Cost, Texas; First Shot of the Texas Revolution Monument". www.texasescapes.com. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- KENDALL, CURLEE (2010-06-15). "TAUCH, WALDINE AMANDA". www.tshaonline.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Palmetto State Park — Texas Parks & Wildlife Department". www.tpwd.state.tx.us. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Gonzales Warm Springs Foundation - Texas Highways". Retrieved 2018-07-24.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- "Texas Almanac: Population History of Counties from 1850–2010" (PDF). Texas Almanac. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-07-24.

External links

- Gonzales County government's website

- Gonzales County from the Handbook of Texas Online