Premiership of Boris Johnson

The premiership of Boris Johnson began on 24 July 2019 when Johnson accepted Queen Elizabeth II's invitation, at her prerogative, to form a government. It followed the resignation of Theresa May, who stood down as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party following Parliament's repeated rejection of her Brexit withdrawal agreement.[1]

| |

| Premiership of Boris Johnson | |

|---|---|

| 24 July 2019 – present | |

| Premier | Boris Johnson |

| Cabinet | 1st Johnson ministry 2nd Johnson ministry |

| Party | Conservative |

| Election | 2019 |

| Appointer | Elizabeth II |

| Seat | 10 Downing Street |

← Theresa May • | |

.svg.png) | |

| Royal Arms of HM Government | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Mayor of London

European Union referendum

Foreign Secretary

Party leadership campaign Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

First ministry and term

Second ministry and term

|

||

The results of the leadership election were announced at an event in Westminster on 23 July 2019. Johnson was declared leader with 92,153 votes, 66.4% of the total ballot, while his competitor Jeremy Hunt received 46,656 votes. In a snap general election in December 2019, Johnson led the Conservative Party to their biggest victory since 1987 (under Margaret Thatcher). Following the election, Parliament ratified Johnson's Brexit withdrawal agreement, and the UK left the European Union on 31 January 2020, beginning an eleven-month transition period.

The global pandemic of COVID-19 emerged as a serious crisis within the country in early 2020, a disease particularly dangerous to the elderly and those with underlying health conditions.[2] In late March, it was announced that Johnson himself had tested positive for the disease.[3]

Bid for Conservative leadership

Theresa May, after failing to pass her Brexit withdrawal agreement through parliament three times, announced her resignation as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom on 24 May 2019 amidst calls for her to be ousted.[4][5] Boris Johnson had already confirmed at a business event in Manchester days earlier that he would run for Conservative Party leader if May were to resign.[6]

Prior to his state visit to the United Kingdom, US president Donald Trump endorsed Johnson for party leader in an interview with The Sun, opining that he thought he "would do a very good job."[7] Johnson won all five rounds of voting by MPs,[1] and entered the final vote by Conservative Party members as the clear favourite to be elected PM.[8] On 23 July, he emerged victorious over his rival Jeremy Hunt with 92,153 votes, 66.4% of the total ballot, while Hunt received 46,656 votes.[9] These results were announced an event in the Queen Elizabeth II Centre in Westminster. In his first speech as Prime Minister Johnson pledged that Britain would leave the European Union (EU) by 31 October 2019, "no ifs or buts".[10]

Appointments

On the day of his announcement as Prime Minister Johnson handed the role of Chief Whip to "relative unknown" Sherwood MP Mark Spencer.[11] Spencer served under the additional title Parliamentary Secretary to the Treasury.

Andrew Griffith, an executive at the media conglomerate Sky, was appointed chief business adviser to Number 10. Munira Mirza, who was a deputy mayor for Johnson throughout his mayoralty of London, was appointed director of the Number 10 Policy Unit.[12] Dominic Cummings, former chief of the Vote Leave campaign, was appointed a role as a senior advisor to Johnson.[13]

Johnson's key cabinet appointments were Sajid Javid as Chancellor of the Exchequer, Dominic Raab as Foreign Secretary and First Secretary of State, and Priti Patel as Home Secretary. Michael Gove moved to become the Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster and was replaced as Environment Secretary by pro-Brexit MP Theresa Villiers. Gavin Williamson became Education Secretary, Andrea Leadsom became Business Secretary, Liz Truss became International Trade Secretary and Grant Shapps became Transport Secretary. Stephen Barclay, Matt Hancock, Amber Rudd and Alun Cairns retained their previous cabinet roles, whilst Julian Smith, Alister Jack and Nicky Morgan took on new roles. Entering cabinet for the first time were Ben Wallace, Robert Jenrick, James Cleverly, Rishi Sunak and Robert Buckland.[14]

First 100 days

.jpg)

Johnson focused on strengthening the Union within his first few days in office, creating a Minister for the Union position and visiting Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Loss of working majority, Conservative MPs and ministerial resignations

On 29 August 2019, Johnson suffered the first ministerial resignation of his premiership, when Lord Young of Cookham resigned as a government whip in the House of Lords.[15]

On 3 September 2019, Phillip Lee crossed the floor and defected to the Liberal Democrats following disagreement with Johnson's Brexit policy. This left the government with no working majority in the House of Commons.[16] Later that day, 21 Conservative MPs including former Chancellors Kenneth Clarke, Philip Hammond and Nicholas Soames, the grandson of former Conservative Party Leader Winston Churchill, had the party whip withdrawn for defying party orders and supporting an opposition motion.[17] Johnson saw his working majority reduced from 1 to minus 43.

On 5 September 2019, Johnson's brother Jo Johnson resigned from the government and announced that he would step down as an MP, describing his position as "torn between family and national interest."[18]

On 7 September 2019, Amber Rudd resigned as Secretary of State for Work and Pensions and from the Conservative Party, describing the withdrawal of the party whip from MPs on 3 September as an "assault on decency and democracy".[19][20]

Prorogation of parliament

On 28 August 2019, Johnson advised the Queen to prorogue parliament between 12 September 2019 and 14 October 2019, which was given ceremonial approval by the Queen at a Privy Council meeting.[21] The prorogation spurred requests for a judicial review of the advice given by Johnson as the order itself, under royal prerogative powers, cannot be challenged in court.[22] As of 29 August, three court proceedings had been lodged, and one European legal proceeding had begun:

- In the Court of Session, Edinburgh, for breach of the Northern Ireland (Executive Formation etc) Act 2019 and the European Union (Withdrawal) Act 2018, by 75 MPs led by Joanna Cherry;[23]

- In the High Court of Justice, Westminster, for an urgent judicial review on the legality of the use of the royal prerogative, by Gina Miller;[24]

- In the High Court, Northern Ireland, for breach of the Good Friday Agreement, by Raymond McCord;[25]

- In the European Parliament, for breach of Article 2 of the Treaty on European Union, under the process outlined under Article 7 of the Treaty on European Union.[26]

On 24 September 2019 the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom found that Johnson's attempt to prorogue Parliament for five weeks "had the effect of frustrating or preventing the constitutional role of Parliament in holding the government to account", that the matter was justiciable, and therefore that the attempted prorogation was unlawful.[27][28] It accordingly declared that the prorogation was void ab initio.[27] Parliament returned the following day and the record was made to show that Parliament was not in fact prorogued but rather "adjourned".[29] On 2 October 2019, Johnson announced his plans to prorogue Parliament on 8 October and hold a new State Opening of Parliament on 14 October.[30]

Brexit plan publication

On 2 October 2019, the government delivered its Brexit proposals to the EU in a seven-page document, including plans to replace the Irish backstop. The proposals would see Northern Ireland stay in the European single market for goods, but leave the customs union, resulting in new customs checks.[31]

Jeremy Corbyn, the leader of the Labour Party, said he did not think Johnson's Brexit plan would get EU support, claiming it was worse than the deal negotiated by former Prime Minister Theresa May. He also said the proposal was "very unspecific on how the Good Friday Agreement can be upheld."[32]

On 4 October, government papers submitted to the Scottish court indicated that Johnson would ask the EU for an extension to the Article 50 process if a deal was not reached by 19 October. However, later the same day Johnson reiterated his earlier statement that the UK would be leaving the EU on 31 October, regardless of whether or not a deal had been reached.[33]

Revised withdrawal agreement

Following negotiations between the UK and EU, a revised withdrawal agreement was reached on 17 October.[34] A special Saturday sitting of Parliament was held two days later to debate the new agreement.[35][36][37] MPs passed an amendment, introduced by Sir Oliver Letwin by 322 votes to 306, withholding Parliament's approval until legislation implementing the deal was passed, and intending to force the government to request a delay from the EU for the exit until 31 January 2020.[38] Later that evening, 10 Downing Street confirmed that Johnson would send a letter to the EU requesting an extension, but would not sign it.[39] EU Council President Donald Tusk subsequently confirmed receipt of the letter, which Johnson had described as "Parliament's letter, not my letter". In addition, Johnson sent a second letter expressing the view that any further delay to Brexit would be a mistake.[39]

On 21 October, the government published the withdrawal agreement bill and proposed three days of debate for opposition MPs to scrutinise it.[40] The Speaker of the House of Commons John Bercow refused a government request to hold a vote on the Brexit deal, citing their previous decision to withdraw it.[41]

The government brought the recently revised EU Withdrawal Bill to the House of Commons for debate on the evening of 22 October 2019.[42] MPs voted on the Bill itself, which was passed by 329 votes to 299, and the timetable for debating the Bill, which was defeated by 322 votes to 308. Prior to the votes, Johnson had stated that if his timetable failed to generate the support needed to pass in parliament he would abandon attempts to get the deal approved and would seek a general election. Following the vote, however, Johnson announced that the legislation would be paused while he consulted with other EU leaders.[42][43]

On 30 October, Johnson took part in a one-hour and eleven minute long session of Prime Minister's Questions – the longest on record. He led tributes to parliamentarian John Bercow who stood down the following day after ten years as Speaker of the House of Commons.[44]

2019 general election

Calls for early election

On 3 September 2019, Johnson threatened to call a general election after opposition and rebel Conservative MPs successfully voted against the government to take control of the order of business with a view to preventing a no-deal exit.[45]

Despite government opposition, the bill to block a no-deal exit passed the Commons on 4 September 2019, causing Johnson to call for a general election on 15 October.[46] However, this motion was unsuccessful as it failed to command the support of two-thirds of the House as required by the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (FTPA).[47] A second attempt at a motion for an early general election failed on 9 September.[48]

After the programme motion for the withdrawal agreement bill failed to pass on 22 October, Johnson once again submitted a motion for an early general election under the FTPA. After the motion failed, the government put forward a short bill to hold another election – a method which needed only a simple majority and not a two thirds majority as required by the FTPA.[49] Opposition MPs submitted an amendment to change the date of the election to 9 December rather than 12 December, but the amendment failed. On 29 October, MPs approved the election for 12 December in a second vote.[50] The date of the election became law when royal assent was given on 31 October.[51]

Campaign

Campaigning for the election began officially on 6 November.[52] Johnson participated in a television debate with Jeremy Corbyn hosted by ITV on 19 November, and one hosted by the BBC on 6 December.[53][54] He worked with Brett O'Donnell, a US Republican strategist, in preparation for the debates,[55] whilst his campaign was managed by Isaac Levido, an Australian strategist.

The Brexit Party leader Nigel Farage had suggested the Brexit and Conservative parties could form an electoral pact to maximise the seats taken by Brexit-supporting MPs, but this was rejected by Johnson.[56]

During the floods which hit parts of England in November, Johnson was criticised for what some saw as his late response to the flooding[57][58] after he said they were not a national emergency.[59]

The Conservatives banned Daily Mirror reporters from Johnson's campaign bus.[60][61]

On 27 November, the Labour Party announced it had obtained leaked government documents; they claimed these showed that, despite claims otherwise, the Conservatives were in trade negotiations with the US over the NHS. The Conservatives said Labour were peddling "conspiracy theories".[62]

Whilst campaigning in his constituency on 29 November, Johnson returned to Downing Street after news of a stabbing on London Bridge. Five people were stabbed and two died from their injuries; Johnson declared the incident an act of terrorism.

Results

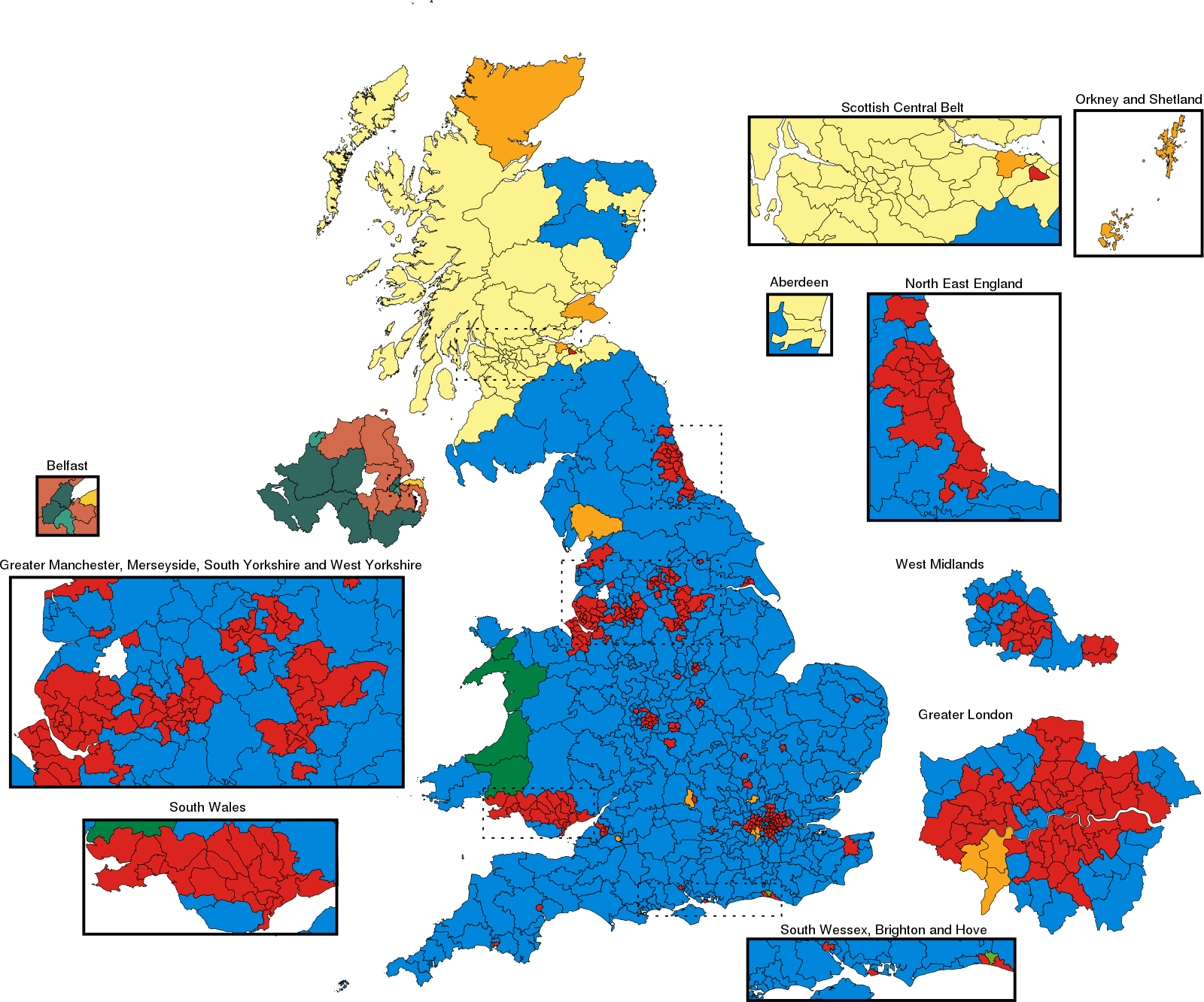

Under Johnson's leadership, the Conservative Party polled their largest share of votes since 1979 and won their largest number of seats since 1987. Their total of 13.9 million votes was the largest number of votes won by any party since 1992. Their victory in the final contest of the election – the seat of St Ives, in Cornwall – took their total number of MPs to 365, giving them a majority of 80.

On the morning of 13 December, after the results of the election were announced, Johnson asked the Queen's permission to form a new government, beginning his second term and organising his second ministry.[63] This remained the same as his first, aside from a new Secretary of State for Wales, to replace Alun Cairns, who resigned after claims that he had known about a former aide's role in the 'sabotage' of a rape trial. Nicky Morgan, who had not stood in the election, and Zac Goldsmith, who lost his seat, were made life peers to allow them to remain in the government.

Brexit Day to transition period

On 18 January 2020, Johnson revealed plans for the Brexit Day celebrations in Downing Street, and the commemorative coin which entered circulation on that day.[64]

On 20 January, in its first defeat since the general election, Johnson's government lost three votes in the House of Lords over its Brexit legislation.[65] However, two days later, he said the UK had "crossed the Brexit finish line" after parliament passed the EU bill for implementing the withdrawal agreement.[66] On 23 January, the bill was given royal assent and the next day it was signed by European leaders in Brussels and by Johnson in Downing Street. The signing in Downing Street was witnessed by both British and European officials, including the Prime Minister's Europe advisor David Frost. There was a vote on the bill in the European Parliament on 29 January where it was ratified by 621 votes to 49.[67][68]

The Department for Exiting the European Union was closed down at 11.01pm on 31 January, a minute after the United Kingdom officially left the European Union.[69]

The Brexit transition period will last until 31 December 2020, an end date that was included in Theresa May's withdrawal agreement. Under an article of the agreement, the UK-EU Joint Committee can decide to extend the transition period by 'up to two years',[70] though Johnson plans to have signed a free-trade deal with the EU by the end of December. During this time the UK remains in the Single Market and Customs Union.

The UK and EU trade negotiations were affected by the COVID-19 pandemic in that videoconferencing was employed by the two sides.[71]

2020 cabinet reshuffle

Johnson conducted a cabinet reshuffle on 13 February 2020 when a number of senior ministers were sacked, including Northern Ireland Secretary Julian Smith, Business Secretary Andrea Leadsom, Environment Secretary Theresa Villiers and Attorney General Geoffrey Cox. Others leaving included Nicky Morgan and James Cleverly. In a surprise move, Sajid Javid resigned as Chancellor and was succeeded by Rishi Sunak. Javid's departure came from a refusal to comply with an order by Johnson to sack his advisory team and replace them with aides from Johnson's office.[72]

Stephen Barclay, Alok Sharma, Brandon Lewis and Oliver Dowden changed their portfolios whilst Anne-Marie Trevelyan, Suella Braverman, George Eustice and Amanda Milling newly joined the cabinet.

Foreign affairs

On 3 January 2020, a US airstrike in Iraq killed the Iranian general Qasem Soleimani. Johnson was not told about the attack by US President Donald Trump prior to it happening. He was criticised for not returning from his holiday in Mustique as tensions between Iran and the west rose.[73]

In a review in 2020, Johnson outlined a review in the UK's approach to foreign policy, the last of which had been carried out in 2015. It included looking at:[74]

- Her Majesty's Diplomatic Service

- Organised crime in the UK

- Military procurement

- The use of technology

It came after the Conservative Party's 2019 general election manifesto said that the UK would spend 0.7% of its gross national income on overseas aid and more than 2% of its gross national product on defence, exceeding the defence spending target set by NATO.[74]

On 16 June 2020, Johnson announced that the Department for International Development would merge with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, to create a new department named the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. The move is expected to be carried out in early September,[75] but has been criticised by the Labour Party and by former Prime Ministers David Cameron, Gordon Brown and Tony Blair.[76]

During the Hong Kong–Mainland China conflict, Johnson's government offered up to three million Hong Kong citizens the opportunity to live in the UK with a "route to citizenship" if they held British National (Overseas) passports.[77]

Foreign trips

Johnson's first overseas trip as Prime Minister was when he travelled to Berlin to meet German Chancellor Angela Merkel on 21 August 2019. He visited France to hold meetings with French President Emmanuel Macron the next day.

Domestic affairs

Johnson welcomed a decision by political parties in Northern Ireland to restore the Northern Ireland Assembly on the basis of negotiations between the British and Irish governments. Talks succeeded under Northern Ireland Secretary Julian Smith to create a 6th Northern Ireland Assembly, which resumed meeting on 11 January 2020. It followed a three-year hiatus with a new power sharing agreement between Sinn Féin and the DUP.

Early spending commitments

On 5 September 2019, Johnson launched a national campaign to recruit 20,000 new police officers.[78]

He also pledged to build 40 new hospitals by 2030.[79]

Transport

On 27 July 2019, Johnson gave a speech at the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester where he promised to build a high-speed rail route connecting the city to Leeds. He said the project would bring "colossal" benefits and "turbo-charge the economy".[80]

Johnson came under pressure to "pay back the trust of Northern voters" after his victory in the 2019 general election. This was a factor in him giving the go-ahead to the High Speed 2 (HS2) project on 11 February 2020.[81] The rail line, capable of speeds above 186 mph, is scheduled to open in phases between 2028 and 2040. It has been criticised for its projected costs and impact on the environment.

Downing Street said that work was underway "by a range of government officials" to look into the prospects of building a bridge from Scotland to Northern Ireland. Johnson has also promoted the idea of an airport in the Thames Estuary, nicknamed "Boris Island".

On 27 February, a court ruling deemed a third runway at Heathrow Airport "unlawful". Johnson said he was not planning to appeal against the ruling. However, the court said that a third runway could be built in the future if it worked in line with the UK's commitments in the Paris Agreement.[82]

5G and Huawei

On 28 January 2020, the UK government decided to let Huawei have a limited role in building its new 5G network and supplying new high-speed network equipment to wireless carriers, whilst ignoring the US government's warnings that it would sever intelligence sharing if they did not exclude the company. The UK government stated that they deemed Huawei as a high-risk vendor but decided against banning the company from its 5G network, and said instead that they had decided to "use Huawei in a limited way so we can collectively manage the risk".[83][84] Several Conservative Party members, on their part, warned against using Huawei.

However, in July 2020, due in part to pressure from the US government, Johnson's government decided not to buy any of Huawei's equipment, and told mobile providers to remove the firm's 5G technology from their networks by 2027.[85][86]

George Floyd protests

Johnson stated that he was "appalled and sickened" by the killing of George Floyd, which lead to protests being held across the UK.[87] He urged people to protest peacefully and said that the protesters who "attack[ed] public property or the police" would "face the full force of the law".[88]

Intelligence and Security Committee Russia report

In July 2020 the newly reconstituted Intelligence and Security Committee report on Russia was released. It stated that the British government and intelligence agencies had failed to conduct any proper assessment of attempts by the Russian government to interfere with the 2016 EU membership referendum. It stated that the government "had not seen or sought evidence of successful interference in UK democratic processes". The committee's Stewart Hosie, an SNP MP, said "The report reveals that no one in government knew if Russia interfered in or sought to influence the referendum because they did not want to know". Yet, the report stated that committee members had said that no firm conclusion could be ascertained on whether the Russian government had or had not successfully interfered in the referendum.[89]

COVID-19 pandemic

By 1 March 2020, cases of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) had reached every nation of the UK. Johnson unveiled the Coronavirus Action Plan and declared the outbreak a 'level 4 incident'. On 6 March he announced £46 million in funding for research into a coronavirus vaccine and rapid diagnostic tests.

On 12 March Johnson said the outbreak represented the "worst public health crisis in a generation" after chairing an emergency COBR meeting. Johnson, and his team of advisers, including Chief Medical Officer Chris Whitty and Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance, held daily press briefings from Downing Street to update the public on developments. The press briefings, which were also chaired by other cabinet ministers, ended on 23 June.[90]

The government advised on measures such as social distancing and advised people in the UK against "non-essential" travel and contact with others, as well as suggesting people should avoid pubs, clubs and theatres, and work from home if possible. Pregnant women, people over the age of 70 and those with certain health conditions were urged to consider the advice "particularly important", and would be asked to self-isolate. Johnson announced that the UK would close the majority of its schools beginning on 20 March.[91] That year's summer exams were cancelled across the UK.[92][93] On 20 March, during the daily 5 pm press conference, Johnson requested the closure of pubs, restaurants, gyms, entertainment venues, museums and galleries that evening, though with some regret, saying "We're taking away the ancient, inalienable right of free-born people of the United Kingdom to go to the pub".[94][95]

On 23 March, in a televised broadcast, Johnson announced wide-ranging restrictions on freedom of movement in the UK, enforceable in law for a period of up to 2 years.[96] The UK had been amongst the last major European states to progressively encourage social distancing, close schools, ban public events and order a lockdown.[97][98]

On 27 March it was announced that Johnson had tested positive for coronavirus.[3] On 5 April he was taken to St Thomas' Hospital in London for tests due to him displaying "persistent symptoms".[99] He was moved to the hospital's intensive care unit the next day as his condition had worsened. First Secretary of State, Dominic Raab began deputising for him "where necessary".[100] After receiving "standard oxygen treatment" in hospital, he was moved out of intensive care on 9 April.[101] He left hospital on 12 April after a week of treatment, and was moved to his country residence, Chequers, to recuperate.[102] After a fortnight at Chequers, he returned to Downing Street on the evening of 26 April and was said to be chairing a government coronavirus "war cabinet" meeting.[103] During the pandemic Johnson also reached a divorce settlement with his estranged wife Marina Wheeler, before giving birth to a son with his partner Carrie Symonds.[104]

On 30 April Johnson said that the country was "past the peak" of the outbreak and spoke about the importance of mask-wearing. He said that to avoid a second peak of infections, it was important to keep the R number below one (the number of cases directly generated by one case).[105] On 10 May he asked those who could not work from home to go to work, avoiding public transport if possible, encouraged the taking of "unlimited amounts" of outdoor exercise, and allowed driving to outdoor destinations within England. The slogan previously used by the government, "Stay at Home", was newly changed to "Stay Alert".[106]

Regarding a controversy about Dominic Cummings' travelling during the lockdown, Johnson used the televised coronavirus update on 24 May to say that he believed he had acted "responsibly, legally and with integrity".[107] There was media pressure for Cummings to resign, or for Johnson to dismiss him.[108]

References

- Stewart, Heather (23 July 2019). "Boris Johnson elected new Tory leader". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Guidance on social distancing for everyone in the UK". GOV.UK. 20 March 2020. Retrieved 20 March 2020.

- "PM Boris Johnson tests positive for coronavirus". BBC News. 27 March 2020. Retrieved 27 March 2020.

- Picheta, Rob (25 May 2019). "Theresa May to resign as UK Prime Minister". CNN. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Theresa May resigns over Brexit: What happened?". BBC News. 24 May 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Boris Johnson confirms bid for Tory leadership". BBC News. 16 May 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Donald Trump says Boris Johnson would be 'excellent' Tory leader". BBC News. 1 June 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- Mason, Rowena (23 July 2019). "Johnson on course to win Tory leadership contest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Boris Johnson wins race to be Tory leader and PM". BBC News. 23 July 2019. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- "Johnson's first 100 days: broken promises and an unlawful prorogation". The Guardian. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Elgot, Jessica (23 July 2019). "Relative unknown Mark Spencer becomes chief whip". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- Syal, Rajeev; Mason, Rowena; O'Carroll, Lisa (23 July 2019). "Sky executive among Johnson's first appointments". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 23 July 2019.

- "Who is 'career psychopath' Dominic Cummings set to join Johnson's team?". Sky News. Retrieved 24 July 2019.

- Sparrow, Andrew; Badshah, Nadeem; Busby, Mattha; O'Carroll, Lisa (24 July 2019). "Boris Johnson cabinet: Sajid Javid, Priti Patel and Dominic Raab given top jobs – as it happened". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "Lord Young quits Tory whip over Boris Johnson's prorogue stance". Metro. 29 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "Boris Johnson loses majority after Tory MP defects during speech". The Independent. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 3 September 2019.

- "Twenty-one Tory rebels lose party whip after backing bid to block no-deal Brexit". PoliticsHome.com. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- "PM's brother quits as Tory MP and minister". BBC News. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 5 September 2019.

- Shipman, Tim (7 September 2019). "Exclusive: Amber Rudd resigns from cabinet and quits Tories". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0140-0460. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- "Amber Rudd quits cabinet and Conservative party". 7 September 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Young, Vicki (28 August 2019). "It's donepic.twitter.com/YGdB0WX4zk". @BBCVickiYoung. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- "How do you suspend Parliament?". 28 August 2019. Retrieved 28 August 2019.

- Carrell, Severin (13 August 2019). "Brexit: judge fast-tracks challenge to stop Johnson forcing no deal". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- O'Carroll, Lisa; Carrell, Severin (28 August 2019). "Gina Miller's lawyers apply to challenge Boris Johnson plan". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- O'Carroll, Lisa (29 August 2019). "Boris Johnson faces third legal battle over prorogation". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "MEPs plan to trigger EU rule of law investigation into Boris Johnson's government over suspension of parliament". The Independent. 28 August 2019. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- "JUDGMENT- R v The Prime Minister [2019] UKSC 41" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United Kingdom. 24 September 2019.

- "Supreme Court: Suspending Parliament was unlawful, judges rule". BBC News. 24 September 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Parliament: MPs and peers return after court rules suspension unlawful". BBC News. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "Parliament to be prorogued next Tuesday". BBC News. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Government publishes new Brexit proposals". 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "Boris Johnson says his Brexit plan will not have checks at Irish border". edition.cnn.com. 2 October 2019. Retrieved 2 October 2019.

- "PM will send Brexit extension letter, court told". BBC News. 4 October 2019.

- Ellyatt, Holly (17 October 2019). "UK and EU agree on new Brexit deal, Boris Johnson says". CNBC. NBC. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Brexit: Special sitting for MPs to decide UK's future". BBC News. 9 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- Murphy, Simon (9 October 2019). "Parliament set for Brexit showdown on 19 October". The Guardian. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

- "Brexit 'super Saturday': your guide to the big day". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. 19 October 2019. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- Stewart, Heather; Proctor, Kate (19 October 2019). "MPs put brakes on Boris Johnson's Brexit deal with rebel amendment". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 19 October 2019.

- "Brexit: PM sends letter to Brussels seeking further delay". BBC News. BBC. 20 October 2019. Retrieved 20 October 2019.

- "Government publishes Brexit bill". BBC News. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "MPs' vote on Brexit deal ruled out by Speaker". BBC News. 21 October 2019. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "MPs reject Brexit bill timetable". BBC News. 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- James, William; MacLellan, Kylie; Piper, Elizabeth (22 October 2019). "Brexit in chaos after parliament defeats Johnson's ratification timetable". Reuters.com. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- Honeycombe-Foster, Matt (30 October 2019). "Boris Johnson leads tributes to 'tennis ball machine' John Bercow as outgoing Speaker chairs longest ever PMQs". PoliticsHome.com. Retrieved 30 October 2019.

- Rayner, Gordon; Sheridan, Danielle (3 September 2019). "Brexit vote result: Boris Johnson demands general election after rebel MPs seize control of Commons agenda" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- "MPs back bill aimed at blocking no-deal Brexit". 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- "Johnson's call for general election rejected by MPs". 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.

- Mason, Rowena (10 September 2019). "Boris Johnson loses sixth vote in six days as election bid fails" – via www.theguardian.com.

- "Early Parliamentary General Election Act 2019". Parliament.uk. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "UK set for 12 December general election after MPs' vote". BBC News. 29 October 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- McGuinness, Alan (31 October 2019). "General election: Legislation to hold early poll becomes law". Sky News. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- "General election 2019: Conservative Party launches campaign". BBC News. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "General election 2019: Lib Dems lodge complaint over ITV leaders' debate". BBC News. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 7 November 2019.

- "General election 2019: Boris Johnson and Jeremy Corbyn to face off in live BBC debate". BBC News. 8 November 2019. Retrieved 11 November 2019.

- "Bush guru prepares Boris Johnson for election debate". The Times. 18 November 2019. Retrieved 19 November 2019.

- Colson, Thomas (2 November 2019). "Boris Johnson will reject Nigel Farage's election offer of a Brexit alliance pact". Business Insider France. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Vinter, Robyn (14 November 2019). "Johnson's slow response to flooding here in Yorkshire could cost him the election". The Guardian.

- "PM Boris Johnson heckled in flood-hit South Yorkshire". BBC News. 13 November 2019.

- Thornton, Lucy (14 November 2019). "Flood victim tells 'little man' Boris Johnson to 'get on his bike' after photo op". Daily Mirror.

- Mayhew, Freddy (21 November 2019). "Mirror barred from Boris Johnson campaign battle bus". Press Gazette.

- Dunt, Ian (22 November 2019). "Week in Review: Tory disinformation campaign intensifies". politics.co.uk.

- Woodcock, Andrew; Kentish, Benjamin (27 November 2019). "Corbyn reveals secret documents that 'confirm Tory plot to sell off NHS in US trade talks with Trump". The Independent.

- "Election results 2019: Boris Johnson hails 'new dawn' after historic victory". BBC News. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Merrick, Rob (18 January 2020). "Boris Johnson announces Brexit day celebrations to distract from failure to make Big Ben bong". The Independent. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Brexit: Government loses first parliamentary votes since election". BBC News. 20 January 2020. Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- "Brexit: UK has 'crossed Brexit finish line', says Boris Johnson". BBC News. 22 January 2020. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "Brexit: Boris Johnson signs withdrawal agreement in Downing Street". BBC News. 24 January 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2020.

- "Brexit: European Parliament overwhelmingly backs terms of UK's exit". BBC News. 29 January 2020. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Duffy, Nick (1 February 2020). "Brexit Secretary Steve Barclay exits cabinet as Boris Johnson shutters department". inews. Retrieved 1 February 2020.

- "Brexit transition period". The Institute for Government. 2 January 2020. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Stone, Jon (11 May 2020). "'They can effectively blame Covid for everything': What coronavirus means for Brexit talks". The Independent. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- Castle, Stephen (13 February 2020). "Sajid Javid, U.K. Finance Chief, Quits as Boris Johnson Shuffles Team". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- "Boris Johnson mocked for 'still being holiday' as tensions between Iran and the west soar". indy100. 4 January 2020. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "Johnson promises 'overhaul' of post-Brexit foreign policy as he launches review". BBC News. 26 February 2020. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "Prime Minister announces merger of Department for International Development and Foreign Office" (Press release). GOV.UK. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "International development and Foreign Office to merge". BBC News. 16 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Ford, Jonathan; Hughes, Laura (14 July 2020). "UK-China relations: from 'golden era' to the deep freeze". Financial Times. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- "National campaign to recruit 20,000 police officers launches today" (Press release). GOV.UK. 5 September 2019. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Campbell, Denis (8 December 2019). "Johnson's '40 new hospitals' pledge costed at up to £24bn". The Guardian. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "PM pledges new northern high-speed rail route". 27 July 2019. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Merrick, Rob; Cowburn, Ashley (27 February 2020). "Heathrow expansion abandoned by government as Boris Johnson spokesman says it will not appeal court ruling". The Independent. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "U.K. Will Allow Huawei To Build Part Of Its 5G Network, Despite U.S. Pressure". NPR. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Press, Associated. "In Snub to US, UK Will Allow China's Huawei in 5G Networks". thediplomat.com. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Corera, Gordon (14 July 2020). "Huawei: UK prepares to change course on 5G kit supplier". BBC News. Retrieved 14 July 2020.

- Scott, Jennifer (24 July 2020). "Boris Johnson: The prime minister's year in No 10". BBC News. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "UK's Johnson 'appalled and sickened' by George Floyd's death". Reuters. 3 June 2020. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Braddick, Imogen (8 June 2020). "Boris Johnson speaks out on George Floyd protests and urges demonstrators to work peacefully to defeat racism". Evening Standard. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Sabbagh, Dan; Harding, Luke; Roth, Andrew (21 July 2020). "Russia report reveals UK government failed to investigate Kremlin interference". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 July 2020.

- Woodcock, Andrew (23 June 2020). "Coronavirus daily briefings to end after today, No 10 announces as lockdown eased". The Independent. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Coronavirus: UK schools, colleges and nurseries to close from Friday". BBC News. 18 March 2020. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- "Exam cancellations to spark 'almighty scramble' in UK admissions". Times Higher Education (THE). 20 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- Sellgren, Katherine; Richardson, Hannah (19 March 2020). "School closures: What will happen now?". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Mendick, Robert (20 March 2020). "Boris Johnson announces 'extraordinary' closure of UK's pubs and restaurants in coronavirus shutdown". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- O'Toole, Fintan (11 April 2020). "Coronavirus has exposed the myth of British exceptionalism". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- "PM announces strict new curbs on life in UK". BBC News. 23 March 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2020.

- "Coronavirus: What are the lockdown measures across Europe?". Deutsche Welle. 1 April 2020. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- Estimating the number of infections and the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in 11 European countries (PDF). Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology (Report). Imperial College London. 30 March 2020. p. 5. doi:10.25561/77731. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Boris Johnson in 'good spirits' in hospital". BBC News. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Boris Johnson moved to intensive care as symptoms worsen". BBC News. 6 April 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

- "PM out of intensive care but remains in hospital". BBC News. 9 April 2020. Retrieved 9 April 2020.

- Mason, Rowena (12 April 2020). "Boris Johnson leaves hospital as he continues recovery from coronavirus". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Boris Johnson's return to work 'a boost for the country'". BBC News. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 27 April 2020.

- O'Flynn, Patrick (23 July 2020). "Boris Johnson's 1st year in Downing Street has been an epic motion picture". The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 July 2020.

- "Coronavirus: Boris Johnson says UK is past the peak of outbreak". BBC News. 30 April 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Prime Minister's statement on coronavirus (COVID-19): 10 May 2020". GOV.UK. 10 May 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- "Coronavirus latest news: Boris Johnson backs Cummings and says he acted 'responsibly, legally and with integrity'". The Telegraph. 24 May 2020. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- "Newspaper headlines: No 10 'chaos' as 'defiant' PM defends Cummings". BBC News. 25 May 2020. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

| British Premierships | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by May |

Johnson Premiership 2019–present |

Incumbent |

.jpg)