Portland, Maine

Portland is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maine and the seat of Cumberland County. Portland's population was 66,215 as of 2019.[5] The Greater Portland metropolitan area is home to over half a million people, the 105th-largest metropolitan area in the United States. Portland's economy relies mostly on the service sector and tourism. The Old Port district is known for its 19th-century architecture and nightlife. Marine industry still plays an important role in the city's economy, with an active waterfront that supports fishing and commercial shipping. The Port of Portland is the largest tonnage seaport in New England.[6]

Portland, Maine | |

|---|---|

| City of Portland, Maine | |

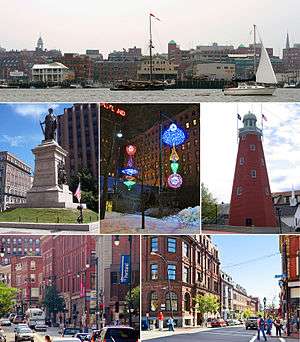

Clockwise: Portland waterfront, the Portland Observatory on Munjoy Hill, the corner of Middle and Exchange Street in the Old Port, Congress Street, the Civil War Memorial in Monument Square, and winter light sculptures in Congress Square Plaza. | |

Flag  Seal | |

| Nickname(s): The Forest City, Portland of the East | |

| Motto(s): Resurgam (Latin) "I Will Rise Again" | |

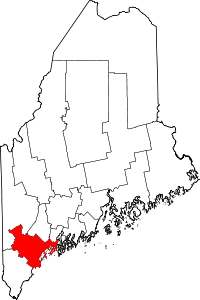

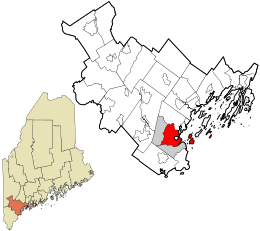

Location within Cumberland County | |

Portland Location within Maine  Portland Location within the United States | |

| Coordinates: 43°40′N 70°16′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Cumberland |

| Settled | 1632 |

| Incorporated | July 4, 1786 |

| Named for | Isle of Portland[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | City council and city manager |

| • City manager | Jon Jennings |

| • Mayor | Kate Snyder |

| • Body | Portland, Maine City Council |

| Area | |

| • City | 69.44 sq mi (179.85 km2) |

| • Land | 21.57 sq mi (55.86 km2) |

| • Water | 47.87 sq mi (123.99 km2) |

| • Urban | 135.91 sq mi (352.0 km2) |

| Elevation | 62 ft (19 m) |

| Population | |

| • City | 66,194 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 66,215 |

| • Rank | US: 519th |

| • Density | 3,069.92/sq mi (1,185.30/km2) |

| • Urban | 243,537 (US: 177th) |

| • Urban density | 1,791/sq mi (692/km2) |

| • Metro | 514,098 (US: 104th) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 04101–04104, 04108–04109, 04112, 04116, 04122–04124 |

| Area code(s) | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-60545 |

| GNIS feature ID | 573692 |

| Website | www |

The city seal depicts a phoenix rising from ashes, a reference to recovery from four devastating fires.[7] Portland was named after the English Isle of Portland, Dorset. In turn, the city of Portland, Oregon was named after Portland, Maine.[8] Portland itself comes from the Old English word Portlanda, which means "land surrounding a harbor".[9]

History

Native Americans, originally called the Portland peninsula Machigonne ("Great Neck").[10] Portland was named for the English Isle of Portland, and the city of Portland, Oregon, was in turn named for Portland, Maine.[11] The first European settler was Capt. Christopher Levett, an English naval captain granted 6,000 acres (2,400 ha) in 1623 to found a settlement in Casco Bay. A member of the Council for New England and agent for Ferdinando Gorges, Levett built a stone house where he left a company of ten men, then returned to England to write a book about his voyage to bolster support for the settlement.[12] Ultimately, the settlement was a failure and the fate of Levett's colonists is unknown. The explorer sailed from England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony to meet John Winthrop in 1630, but never returned to Maine. Fort Levett in the harbor is named for him.

The peninsula was settled in 1632 as a fishing and trading village named Casco.[10] When the Massachusetts Bay Colony took over Casco Bay in 1658, the town's name changed again to Falmouth. In 1676, the village was destroyed by the Abenaki during King Philip's War. It was rebuilt. During King William's War, a raiding party of French and their native allies attacked and largely destroyed it again in the Battle of Fort Loyal (1690).

On October 18, 1775, Falmouth was burned in the Revolution by the Royal Navy under command of Captain Henry Mowat.[13] Following the war, a section of Falmouth called The Neck developed as a commercial port and began to grow rapidly as a shipping center. In 1786, the citizens of Falmouth formed a separate town in Falmouth Neck and named it Portland, after the isle off the coast of Dorset, England.[1] Portland's economy was greatly stressed by the Embargo Act of 1807 (prohibition of trade with the British), which ended in 1809, and the War of 1812, which ended in 1815.

In 1820, Maine was established as a state with Portland as its capital. In 1832, the capital was moved north and East to Augusta. In 1851, Maine led the nation by passing the first state law prohibiting the sale of alcohol except for "medicinal, mechanical or manufacturing purposes." The law subsequently became known as the Maine law, as 18 states quickly followed. On June 2, 1855, the Portland Rum Riot occurred.

In 1853, upon completion of the Grand Trunk Railway to Montreal, Portland became the primary ice-free winter seaport for Canadian exports. The Portland Company manufactured more than 600 19th-century steam locomotives. Portland became a 20th-century rail hub as five additional rail lines merged into Portland Terminal Company in 1911. Following nationalization of the Grand Trunk system in 1923, Canadian export traffic was diverted from Portland to Halifax, Nova Scotia, resulting in marked local economic decline. In the 20th century, icebreakers later enabled ships to reach Montreal in winter, drastically reducing Portland's role as a winter port for Canada.

On June 26, 1863, a Confederate raiding party led by Captain Charles Read entered the harbor at Portland leading to the Battle of Portland Harbor, one of the northernmost battles of the Civil War. The 1866 Great Fire of Portland, Maine, on July 4, 1866, ignited during the Independence Day celebration, destroyed most of the commercial buildings in the city, half the churches and hundreds of homes. More than 10,000 people were left homeless.

By act of the Maine Legislature in 1899, Portland annexed the city of Deering,[14] despite a vote by Deering residents rejecting the annexation, thereby greatly increasing the size of the city and opening areas for development beyond the peninsula.[15]

The construction of The Maine Mall, an indoor shopping center established in the suburb of South Portland, during the 1970s, economically depressed downtown Portland. The trend reversed when tourists and new businesses started revitalizing the old seaport, a part of which is known locally as the Old Port. Since the 1990s, the historically industrial Bayside neighborhood has seen rapid development, including attracting a Whole Foods and Trader Joes supermarkets, as well as Baxter Academy for Technology and Science, an increasingly popular charter school. Other rapidly developing neighborhoods include the India Street neighborhood near the Ocean Gateway and Munjoy Hill, where many modern condos have been built.[16][17][18] The Maine College of Art has been a revitalizing force downtown, attracting students from around the country. The historic Porteous building on Congress Street was restored by the College. Portland is known as a very walkable city, offering many opportunities for walking tours that feature its maritime and architectural history.[19]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 69.44 square miles (179.85 km2), of which 21.31 square miles (55.19 km2) is land and 48.13 square miles (124.66 km2) is water.[20] Portland is situated on a peninsula in Casco Bay on the Gulf of Maine and the Atlantic Ocean.

Portland borders South Portland, Westbrook and Falmouth. The city is located at 43.66713 N, 70.20717 W.

Climate

Portland has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfb), with cold, snowy, and often prolonged winters, and warm, relatively short summers. The monthly average high temperature ranges from roughly 30 °F (−1 °C) in January to around 80 °F (27 °C) in July. Daily high temperatures reach or exceed 90 °F (32 °C) on only 4 days per year on average, while cold-season lows of 0 °F (−18 °C) or below are reached on 10 nights per year on average.[21] The area can be affected by severe nor'easters during winter, with high winds and snowfall totals often measuring over a foot. Annual liquid precipitation (rain) averages 47.2 inches (1,200 mm) and is plentiful year-round, but with a slightly drier summer. Annual frozen precipitation (snow) averages 62 inches (157 cm) in the city. However, neighborhoods away from the immediate coast average slightly more, as the warmer ocean waters and onshore flow can cause snow to transition to sleet or rain along the coast. In Southern Maine, winter-season snowstorms can be intense from November through early April, while warm-season thunderstorms are somewhat less frequent than in the Midwestern, Mid-Atlantic, and Southeastern U.S. Direct strikes by hurricanes or tropical storms are rare, partially due to the normally cooler Atlantic waters off the Maine coast (which usually weaken tropical systems), but primarily because most tropical systems approaching or reaching 40 degrees North latitude recurve (due to the Coriolis force) and track east out to sea well south of the Portland area. Extreme temperatures range from −39 °F (−39 °C) on February 16, 1943, to 103 °F (39 °C) on July 4, 1911, and August 2, 1975.[21]

| Climate data for Portland International Jetport, Maine (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1871–present[lower-alpha 2] precipitation and snowfall records date to 1871 and 1882, respectively.</ref>) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

68 (20) |

88 (31) |

92 (33) |

94 (34) |

98 (37) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

95 (35) |

88 (31) |

74 (23) |

71 (22) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 50.2 (10.1) |

51.4 (10.8) |

61.5 (16.4) |

74.7 (23.7) |

83.8 (28.8) |

88.8 (31.6) |

91.3 (32.9) |

90.1 (32.3) |

85.6 (29.8) |

74.7 (23.7) |

65.3 (18.5) |

55.6 (13.1) |

93.4 (34.1) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 31.2 (−0.4) |

34.6 (1.4) |

42.1 (5.6) |

53.3 (11.8) |

63.5 (17.5) |

73.2 (22.9) |

78.8 (26.0) |

77.7 (25.4) |

70.0 (21.1) |

58.7 (14.8) |

48.0 (8.9) |

37.3 (2.9) |

55.8 (13.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 13.4 (−10.3) |

16.4 (−8.7) |

24.9 (−3.9) |

34.7 (1.5) |

44.2 (6.8) |

53.6 (12.0) |

59.4 (15.2) |

58.2 (14.6) |

50.3 (10.2) |

38.9 (3.8) |

30.9 (−0.6) |

20.4 (−6.4) |

37.2 (2.9) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −7 (−22) |

−3.1 (−19.5) |

5.9 (−14.5) |

23.9 (−4.5) |

32.2 (0.1) |

42.6 (5.9) |

49.9 (9.9) |

46.7 (8.2) |

36.5 (2.5) |

25.6 (−3.6) |

16.1 (−8.8) |

2.1 (−16.6) |

−9.9 (−23.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−39 (−39) |

−21 (−29) |

8 (−13) |

23 (−5) |

33 (1) |

40 (4) |

33 (1) |

23 (−5) |

15 (−9) |

3 (−16) |

−21 (−29) |

−39 (−39) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.38 (86) |

3.25 (83) |

4.24 (108) |

4.32 (110) |

4.01 (102) |

3.79 (96) |

3.61 (92) |

3.14 (80) |

3.69 (94) |

4.87 (124) |

4.93 (125) |

4.02 (102) |

47.25 (1,200) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 19.2 (49) |

12.1 (31) |

12.7 (32) |

2.8 (7.1) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

trace | 1.9 (4.8) |

13.2 (34) |

61.9 (157) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 11.1 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 11.2 | 12.6 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 10.5 | 11.2 | 11.5 | 130.9 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 7.9 | 6.1 | 5.1 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.5 | 6.1 | 27.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.8 | 65.2 | 66.3 | 66.8 | 71.1 | 74.7 | 75.3 | 76.3 | 76.7 | 73.9 | 72.6 | 70.2 | 71.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 164.8 | 172.8 | 205.2 | 213.5 | 243.2 | 259.1 | 282.2 | 267.6 | 229.1 | 195.7 | 138.7 | 140.9 | 2,512.8 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 57 | 59 | 55 | 53 | 53 | 56 | 60 | 62 | 61 | 57 | 48 | 51 | 56 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[21][22][23] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas [24] | |||||||||||||

| Water temperatures | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average sea temperature °F (°C) | 41.3 (5.2) |

38.8 (3.8) |

38.0 (3.3) |

41.6 (5.3) |

46.7 (8.1) |

54.6 (12.6) |

61.3 (16.3) |

63.7 (17.7) |

60.5 (15.8) |

54.9 (12.8) |

49.6 (9.8) |

45.3 (7.4) |

49.7 (9.8) |

| Source: Weather Atlas [24] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

Portland is organized into neighborhoods generally recognized by residents,[25] but they have no legal or political authority. In many cases, city signs identify neighborhoods or intersections (which are often called corners). Most city neighborhoods have a local association[26] which usually maintains ongoing relations of varying degrees with the city government on issues affecting the neighborhood.

On March 8, 1899, Portland annexed the neighboring city of Deering.[27] Deering neighborhoods now comprise the northern and eastern sections of the city before the merger. Portland's Deering High School was formerly the public high school for Deering.

Portland's neighborhoods include the Arts District; Bayside; Bradley's Corner; Cushing's Island; Deering Center; Deering Highlands; Downtown; East Deering; East Bayside; East End; Eastern Cemetery; Great Diamond Island; Highlands; Kennedy Park; Libbytown;[28] Little Diamond Island; Lunt's Corner; Morrill's Corner; Munjoy Hill; Nason's Corner; North Deering; Oakdale; the Old Port; Parkside; Peaks Island; Riverton Park; Rosemont; Stroudwater; West End; and Woodford's Corner.

Starting in the mid-2000s and continuing into the 2010s, many of Portland's neighborhoods have faced gentrification. In 2015, the Portland Press Herald published a series of articles documenting the "super-tight apartment market" and the trauma caused by evictions and steep jumps in monthly rent.[29] Also in that year, city landlords raised rents by an average of 17.4%, which was the second largest jump in the country.[30]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 2,240 | — | |

| 1800 | 3,704 | 65.4% | |

| 1810 | 7,169 | 93.5% | |

| 1820 | 8,581 | 19.7% | |

| 1830 | 12,598 | 46.8% | |

| 1840 | 15,218 | 20.8% | |

| 1850 | 20,815 | 36.8% | |

| 1860 | 26,341 | 26.5% | |

| 1870 | 31,413 | 19.3% | |

| 1880 | 33,810 | 7.6% | |

| 1890 | 36,425 | 7.7% | |

| 1900 | 50,145 | 37.7% | |

| 1910 | 58,571 | 16.8% | |

| 1920 | 69,272 | 18.3% | |

| 1930 | 70,810 | 2.2% | |

| 1940 | 73,643 | 4.0% | |

| 1950 | 77,634 | 5.4% | |

| 1960 | 72,566 | −6.5% | |

| 1970 | 65,116 | −10.3% | |

| 1980 | 61,572 | −5.4% | |

| 1990 | 64,358 | 4.5% | |

| 2000 | 64,249 | −0.2% | |

| 2010 | 66,194 | 3.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 66,215 | [4] | 0.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[31] Raymond H. Fogler Library[32] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[33] of 2010, there were 66,194 people, 30,725 households, and 13,324 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,106.2 inhabitants per square mile (1,199.3/km2). There were 33,836 housing units at an average density of 1,587.8 per square mile (613.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 85.0% White (83.6% non-Hispanic White alone), down from 96.6% in 1990,[34] 7.1% African American, 0.5% Native American, 3.5% Asian, 1.2% from other races, and 2.7% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 3.0% of the population. 40.7% of the population had a bachelor's degree or higher. Men's Health ranked Portland the ninth most educated city in America.[35]

There were 30,725 households, of which 20.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29.7% were married couples living together, 10.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 3.6% had a male householder with no wife present, and 56.6% were non-families. 40.5% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.4% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.07 and the average family size was 2.88.

The median age in the city was 36.7 years. 17.1% of residents were under the age of 18; 11.4% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 33.1% were from 25 to 44; 25.9% were from 45 to 64; and 12.6% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.8% male and 51.2% female.

.jpg)

2000 census

As of the census of 2000, there were 64,250 people, 29,714 households, and 13,549 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,029.2 people per square mile (1,169.6/km2). There were 31,862 housing units at an average density of 1,502.2 per square mile (580.0/km2).

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, Portland's immediate metropolitan area ranked 147th in the nation in 2000 with a population of 243,537, while the Portland/South Portland/Biddeford metropolitan area included 487,568 total inhabitants. This has increased to an estimated 513,102 inhabitants (and the largest metro area in Northern New England) as of 2007.[36] Much of this increase in population has been due to growth in the city's southern and western suburbs.

The racial makeup of the city was 91.27% White, 2.59% African American, 0.47% Native American, 3.08% Asian, 0.06% Pacific Islander, 0.67% from other races, and 1.86% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.52% of the population.

The largest ancestries include: British (including Scottish, Welsh, and English) (21.2%), Irish (19.2%), French (10.8%), Italian (10.5%), and German (6.9%).[37]

There were 29,714 households, out of which 21.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32.1% were married couples living together, 10.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 54.4% were non-families. 40.1% of all households were made up of individuals, and 11.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.08 and the average family size was 2.89.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 18.8% under the age of 18, 10.7% from 18 to 24, 36.1% from 25 to 44, 20.6% from 45 to 64, and 13.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 91.8 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 89.0 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,650, and the median income for a family was $48,763. Males had a median income of $31,828 versus $27,173 for females. The per capita income for the city was $22,698. About 9.7% of families and 14.1% of the population were below the poverty line, including 12.5% of those under age 18 and 11.9% of those age 65 or over.

Race/ethnicity composition

| Race/ethnicity | 2010[38] | 2000[39] | 1990[40] | 1960[40] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 83.6% | 91.27% | 96% | 99.4% |

| African Americans | 7.1% | 2.59% | 1.1% | 0.5% |

| Asian | 3.5% | 3.08% | 1.7% | 0.1% |

| Two or more races | 2.7% | 1.86% | 0.2% | NA |

| Hispanic or Latino | 3.0% | 1.52% | 0.8% | NA |

| Native American | 0.5% | 0.47% | 0.4% | NA |

Economy

Portland has become Maine's economic capital because the city has Maine's largest port, largest population, and is close to Boston (105 miles to the south). Over the years, the local economy has shifted from fishing, manufacturing, and agriculture towards a more service-based economy. Most national financial services organizations such as Bank of America and Key Bank base their Maine operations in Portland. Unum, TruChoice Federal Credit Union, People's United Bank, ImmuCell Corp, and Pioneer Telephone have headquarters here, and Portland's neighboring cities of South Portland, Westbrook and Scarborough, provide homes for other corporations including IDEXX and WEX Inc. Since 1867, Burnham & Morrill Co., maker of B&M Baked Beans, has had its main plant in Portland and is considered a landmark.

The city's port is also undergoing a revival and the first-ever container train departed from the new International Marine Terminal with 15 containers of locally produced bottled water in early 2016.[41]

Americold, a US-based international provider of temperature-controlled storage and distribution, won a bid to develop a state-of-the-art temperature-controlled storage facility adjacent to the port. The facility will support perishable produce, meats, and seafood imports with direct exports but construction has not yet begun.

Portland has a low unemployment rate (3% in June 2017) when compared to national and state averages.[42] The city and its adjacent communities also have higher median incomes than most of the state.

In January 2020 Portland was announced to be the location of a new research institute that will focus on the application of artificial intelligence and machine learning. Northeastern University was selected by technology entrepreneur David Roux to lead the institute that will include programs that will allow graduate student research.[43]

Portland also has a large subsidized housing industry with more than five large real estate companies entirely in the business.

Culture

Portland has a long history of prominence in the arts, peaking the first time in the early nineteenth century, when the city was "a rival, and not a satellite of either Boston or New York."[44] In that period, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow got his start as a young poet and John Neal held a central position in leading American literature toward its great renaissance.[45][46] Other notable literary or artistic figures who got their start or were at their prime in that period include Grenville Mellen, Nathaniel Parker Willis, Seba Smith, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, Benjamin Paul Akers, Charles Codman, Franklin Simmons, John Rollin Tilton, and Harrison Bird Brown. Portland has enjoyed an arts-related revitalization since the late twentieth century.

Sites of interest

The Arts District, centered on Congress Street, is home to the Portland Museum of Art, Portland Stage Company, Maine Historical Society & Museum, Portland Public Library, Maine College of Art, Children's Museum of Maine, Merrill Auditorium, the Kotzschmar Memorial Organ, and Portland Symphony Orchestra, as well as many smaller art galleries and studios.

Baxter Boulevard around Back Cove, Deering Oaks Park, the Eastern Promenade, Western Promenade, Lincoln Park and Riverton Park are all historical parks within the city. Other parks and natural spaces include Payson Park, Post Office Park, Baxter Woods, Evergreen Cemetery, Western Cemetery and the Fore River Sanctuary.

Thompson's Point, in the Libbytown neighborhood, has been a focus of renovation and redevelopment during the 2010s. The location hosts a concert venue, ice rink, hotels, restaurants, wineries, and breweries.[47]

Other sites of interest include:

- Casco Bay Islands

- Cross Insurance Arena

- East End Beach

- Exchange Street (the "Old Port" area)

- Hadlock Field, home of the Portland Sea Dogs

- Portland Exposition Building, home of the Maine Red Claws

- Longfellow Arboretum

- Neal S. Dow House

- Maine Narrow Gauge Railroad Museum

- Martin's Point

- McLellan-Sweat Mansion

- The Portland Club

- Portland Head Light Lighthouse

- Portland Observatory

- Portland Stage Company

- University of New England

- University of Southern Maine (USM)

- Victoria Mansion

- Wadsworth-Longfellow House

Public parks

The city of Portland includes more than 700 acres of open space and public parks. The city and surrounding communities are linked by 70 miles of trails, both urban and wooded, maintained by the nonprofit Portland Trails. The city requires organic land care techniques be used on both public and private property.[48] In 2018, the Portland City Council banned the use of synthetic pesticides.[49]

Well-known and historic parks include:

- Deering Oaks Park

- Eastern Promenade

- Western Promenade

- Baxter Boulevard

- Lincoln Park

- Congress Square Park

- Payson Park

- East End Beach

- Riverside Municipal Golf Course

- Fort Sumner Park

- Baxter Woods

- Fore River Sanctuary

- Quarry Run Dog Park

- Riverton Trolley Park

Notable buildings

The spire of the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception has been a notable feature of the Portland skyline since its completion in 1854. In 1859, Ammi B. Young designed the Marine Hospital, the first of three local works by Supervising Architects of the U.S. Treasury Department. Although the city lost to redevelopment its 1867 Greek Revival post office, which was designed by Alfred B. Mullett of white Vermont marble and featured a Corinthian portico, Portland retains his equally monumental 1872 granite Second Empire–Renaissance Revival custom house.

A more recent building of note is Franklin Towers, a 16-story residential tower completed in 1969. At 175 feet (53 meters),[50] it is Portland's (as well as Maine's) tallest building. It is next to the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception on the city skyline. During the building boom of the 1980s, several new buildings rose on the peninsula, including the 1983 Charles Shipman Payson Building by Henry N. Cobb of Pei, Cobb, Freed & Partners at the Portland Museum of Art complex (a component of which is the 1801 McLellan-Sweat Mansion), and the Back Bay Tower, a 15-story residential building completed in 1990.[51]

477 Congress Street (known locally as the Time and Temperature Building) is situated near Monument Square in the Arts District and is a major landmark: the 14-story building features a large electronic sign on its roof that flashes time and temperature data, as well as parking ban information in the winter. The sign can be seen from nearly all of downtown Portland. The building is home to several radio stations.

The Westin Portland Harborview, completed in 1927, is a prominent hotel located downtown on High Street. Photographer Todd Webb lived in Portland during his later years and took many pictures of the city.[52] Some of Webb's pictures can be found at the Evans Gallery.[53]

Notable people

Media

Portland is home to a concentration of publishing and broadcast companies, advertising agencies, web designers, commercial photography studios, and film makers.

The city is home to two daily newspapers: The Portland Press Herald/Maine Sunday Telegram (founded in 1862) and The Portland Daily Sun. The Press Herald is published Monday through Saturday and The Maine Sunday Telegram is published on Sundays. Both are published by MaineToday Media Inc., which also operates an entertainment website, MaineToday.com and owns papers in Augusta, Waterville, and Bath. The Daily Sun began operations in 2009 and is owned by the Conway Daily Sun of North Conway, New Hampshire.

Portland is also covered by an alternative weekly newspaper, The Portland Phoenix, published by the Phoenix Media/Communications Group, which also produces a New England-wide news, arts, and entertainment website, thephoenix.com, and a twice-annual LGBT issues magazine, Out in Maine.

Other publications include The Portland Forecaster, a weekly newspaper; Mainer, a monthly alternative magazine formerly known as The Bollard; The West End News, The Munjoy Hill Observer, The Baysider, The Waterfront, Portland Magazine, and The Companion, an LGBT publication. Portland is also the home office of The Exception Magazine, an online newspaper that covers Maine.

The Portland broadcast media market is the largest one in Maine in both radio and television. A whole host of radio stations are located in Portland, including WFNK (Classic Hits), WJJB (Sports), WTHT (Country), WBQW (Classical), WHXR (Rock), WHOM (Adult Contemporary), WJBQ (Top 40), WCLZ (Adult Album Alternative), WBLM (Classic Rock), WYNZ ('60s-'70s Hits), and WCYY (Modern rock). WMPG is a local non-commercial radio station run by community members and the University of Southern Maine. The Maine Public Broadcasting Network's (MPBN) radio news operations are based in Portland.

The area is served by local television stations representing most of the television networks. These stations include WCSH 6 (NBC), WMTW 8 (ABC), WGME 13 (CBS), WPFO 23 (Fox), WIPL 35 (ION), and WPXT 51 (The CW; MyNetworkTV on DT3). There is no PBS affiliate licensed to the city of Portland, but the market is served by MPBN outlets WCBB Channel 10 in Augusta and WMEA-TV Channel 26 Biddeford.

| TV Channel Number on Cable | Call Sign | Network | Owner |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 | WCSH | NBC | Tegna Inc. |

| 8 | WMTW | ABC | Hearst Television |

| 10 | WCBB | PBS | Maine Public Broadcasting Network |

| 13 | WGME | CBS | Sinclair Broadcast Group |

| 23 | WPFO | Fox | Cunningham Broadcasting |

| 26 | WMEA-TV | PBS | Maine Public Broadcasting Network |

| 35 | WIPL | Ion Television | Ion Media |

| 51 | WPXT | The CW MyNetworkTV (DT3) |

Hearst Television |

Movies filmed in Portland

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Established | Championships |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Portland Sea Dogs | Eastern League, Baseball | Hadlock Field | 1994 | 1 |

| Maine Mariners | ECHL, Ice hockey | Cross Insurance Arena | 2018 | 0 |

| Maine Red Claws | NBA G League, Basketball | Portland Exposition Building | 2009 | 0 |

| GPS Portland Phoenix | USL League Two, Soccer | Memorial Stadium | 2009 | 0 |

| Portland Rugby Football Club | New England Rugby Football Union, Rugby Union | Fox Street Field | 1969 | 1 |

| Maine Roller Derby | WFTDA, Roller Derby | Portland Exposition Building | 2006 | 0 |

| Portland Lumberjacks | PBA Tour,

Professional Bowling Team |

Bayside Bowl | 2016 | 1 |

| Maine Cats | USAFL, Aussie Rules Football | Dougherty Field | 2018 | 0 |

The city is home to three minor league teams. The Portland Sea Dogs, the Double-A farm team of the Boston Red Sox, play at Hadlock Field. The Maine Red Claws, the NBA G League affiliate of the Boston Celtics, play at the Portland Exposition Building. The GPS Portland Phoenix soccer teams plays in USL League Two.

Previously, Portland was home of several minor league ice hockey teams: the Maine Nordiques (NAHL) from 1973 to 1977, the Maine Mariners (AHL) from 1977 to 1992, and the Portland Pirates (AHL) from 1993 to 2016. The Mariners were three-time Calder Cup winners. In 2018, another Maine Mariners, an ECHL team, returned a minor league hockey team to Portland.

The Maine Mammoths of the National Arena League played in 2018 and were the first indoor football team to call Portland home. The team suspended operations after one season while it negotiated with local ownership groups.

The Portland Sports Complex, located off of Park and Brighton Avenues near I-295 and Deering Oaks park, houses several of the city's stadiums and arenas, including:

- Hadlock Field – baseball (Capacity 7,368)

- Fitzpatrick Stadium – football, soccer, lacrosse, field hockey, and outdoor track (Capacity 6,000+ seated)

- Portland Exposition Building – basketball, indoor track, concerts and trade shows (Capacity 3,000)

- Portland Ice Arena – hockey and figure skating (Capacity 400)

Cross Insurance Arena has 6,733 permanent seats following renovation in 2014.

The Portland area has eleven professional golf courses, 124 tennis courts, and 95 playgrounds. There are also over 100 miles (160 km) of nature trails.

Portland hosts the Maine Marathon each October.

Bayside Bowl was expanded in 2017 to 20 lanes, including a rooftop deck. It hosted the 2017 PBA League and Elias Cup.

Memorial Stadium is the home of the Deering High School sports teams and is located behind the school.

Food and beverage

Number of restaurants

Downtown Portland, including the Arts District and the Old Port, has a high concentration of eating and drinking establishments, with many more to be found throughout the rest of the peninsula, outlying neighborhoods, and neighboring communities.

Portland ranks among the top U.S. cities in restaurants and bars per capita. According to the TripAdvisor, Portland is currently home to about 389 restaurants in 2017.[54] Notable restaurants include Fore Street, Duckfat, Amato's, Becky's Diner, Marcy's Dinner, Green Elephant Vegetarian Bistro, Back Bay Grill,[55] Street & Co., and Công Tū Bôt.[56]

The city is home to numerous food trucks and food carts,[57] which park on the city streets and at festivals, events and breweries. Most operate in the summer; a few operate year round.

Food recognition

Portland has developed a national reputation for the quality of its restaurants, eateries, and food culture. In 2018, Portland was named Restaurant City of the Year by Bon Appétit Magazine, which in 2009 had named Portland the "Foodiest Small Town in America."[58][59] Many local chefs have gained national attention over the past few years.[60][61][62] In 2017, Zagat named Portland one of the "30 Most Exciting Food Cities in America."[63]

In 2015, Portland ranked 14th on Travel + Leisure's end-of-year list, "America's 20 Best Cities for Beer Lovers."[64] In 2016, Portland was ranked "top craft beer city in the world" by Matador Network.[65]

In 2019, Rent.com named Portland #6 on its list of Best Cities in America for Vegans.[66][67] In 2016, VegNews magazine added the city to its list of the 12 Best Towns for Vegan Living.[68] In 2015, The Daily Meal named Portland, Maine one of 10 Great American Cities for Vegans.[69]

Portland has been visited by many food shows including Rachael Ray's Food Network show $40 a Day, the Travel Channel's Man v. Food, and Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations.[70][71][72]

Beverages

Portland is home to numerous juice bars,[73] coffee shops, coffee roasteries,[74] tea houses, distilleries, microbreweries and brewpubs, including the D. L. Geary Brewing Company, Gritty McDuff's Brewing Company, Shipyard Brewing Company, Casco Bay Brewing Co., Bissell Brothers Brewery, Austin Street Brewery, Lone Pine, Foundation Brewing Company, Oxbow Blending and Bottling, and Allagash Brewing Company.

Portland's spirits industry has also grown in recent years. Distilleries include Three of Strong Spirits, New England Distilling Co., Stroudwater Distillery, Maine Craft Distillery, Hardshore Distilling Company, and Liquid Riot Bottling Company.[75][76]

The city is known for its pure tap water. The water comes from Sebago Lake. It is piped to Portland by the Portland Water District. Sebago Lake is one of 50 surface water supplies among 13,000 in the country that the Environmental Protection Agency says do not need filtration.[77]

Farmers markets

The Portland Farmers Market, which has been in continuous operation since 1768, takes place Wednesdays in Monument Square, Saturdays in Deering Oaks Park (from early May to the end of November), and Saturdays at The Maine Girls Academy (from early December to the end of April).

Vegetarian food

In 2020, the Portland Press Herald reported that "Portland has gained a national reputation as a top city for vegans."[78] The city has the state's most vegan and vegetarian restaurants that include the Green Elephant Vegetarian Bistro, which opened in 2007, Nura and Copper Branch. Vegetarian-friendly restaurants number more than 200 in 2020 according to the Maine Sunday Telegram.[79]

In the 1970s and 1980s, The Hollow Reed was a notable vegetarian restaurant on Fore Street.[80] Celebrity chef Toni Fiore first filmed the PBS cooking show Totally Vegetarian in 2002 at the cable access station in Portland.[81] The Portland Press Herald has featured a vegan column by Avery Yale Kamila in its Food & Dining section since 2009.[82][83] In 2011, the Portland Public Schools added a daily vegetarian cold lunch option to its school menus. In 2019, the district changed to a daily hot vegan school meal option.[84]

Food festivals

Portland hosts a number of food and beverage festivals, including:

- Festival of Nations, takes place in July in Deering Oaks Park and organized by group of local organizations[85]

- Greek Festival, three-day event in June at Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church[86]

- Harvest on the Harbor, multi-day event takes place in October[87]

- Italian Street Festival & Bazaar, three-day event in August outside St. Peter's Parish commemorates the Feast of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Feast of Saint Rocco[88]

- Maine Brewers Festival, held multiple times a year by the Maine Brewers' Guild[89]

- Maine VegFest, takes place in October and organized by Maine Animal Coalition since 2005; the event features all vegan food and was originally called Maine Vegetarian Food Festival[90]

- Taste of the Nation, fundraiser for food insecurity that stopped after 2015 but happened again in 2019[91]

- Maine Restaurant Week, takes place over 12 days in March[92]

- Maine Seaweed Week, takes place in the spring[93]

Food history

Portland is where national Prohibition started. Portland mayor and temperance leader Neal Dow led Maine to ban alcohol sales in 1851.[94] The law led to the Portland Rum Riot in 1855. Canned corn was developed in Portland by the N. Winslow company. By 1852 the Winslow's Patent Hermetically Sealed Green Corn was a commercial success and the company became a world leader in the canning industry.[95][96] The city's Amato's Italian delicatessen claims to be the birthplace of the Italian sandwich, called "an Italian" by locals, which Amato's first served in 1903.[97] An historic B&M Baked Beans plant built in 1913 remains in operation on the waterfront.[98]

Government

The city has adopted a council-manager style government that is detailed in the city charter. The citizens of Portland are represented by a nine-member city council which makes policy, passes ordinances, approves appropriations, appoints the city manager and oversees the municipal government. The city council of nine members is elected by the citizens of Portland. The city has five voting districts, with each district electing a city councilor to represent their neighborhood interests for a three-year term. There are also four members of the city council who are elected at-large.[99]

From 1923 until 2011, city councilors chose one of themselves each year to serve as Mayor of Portland, a primarily ceremonial position. On November 2, 2010, Portland voters narrowly approved a measure that allowed them to elect the mayor. On November 8, 2011, former State Senator and candidate for U.S. Congress Michael F. Brennan was elected as mayor. On December 5, 2011, he was sworn in as the first citizen-elected mayor in 88 years (see Portland, Maine mayoral election, 2011). The office of mayor is a four-year position that earns a salary of 150% of the city's median income.[100] The current mayor is Kate Snyder, who defeated incumbent mayor Ethan Strimling in the 2019 Portland, Maine mayoral election.

A city manager is appointed by the city council. The city manager oversees the daily operations of the city government, appoints the heads of city departments, and prepares annual budgets. The city manager directs all city agencies and departments, and is responsible for the executing laws and policies passed by the city council.[99] The current city manager is Jon Jennings.

Aside from the main city council, there is also an elected school board for the Portland Public School system. The school board is made up in the same manner of the city council, with five district members, four at-large members and one chairman.[101] There are also three students from the local high schools elected to serve on the board. There are many other boards and committees such as the Planning Committee, Board of Appeals, and Harbor Commission, etc. These committees and boards have limited power in their respective areas of expertise. Members of boards and committees are appointed by city council members.

On November 5, 2013, Portland voters overwhelmingly approved an ordinance to legalize the possession and private use of cannabis for adults, making the city the first municipality in the Eastern United States to do so.[102]

| Year | Democratic | Republican |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 75.9% 28,534 | 18.1% 6,789 |

| 2012 | 76.3% 27,739 | 20.6% 7,488 |

| 2008 | 76.9% 28,317 | 21.3% 7,844 |

| 2004 | 72.6% 26,800 | 25.6% 9,455 |

| 2000 | 63.4% 20,506 | 27.3% 8,838 |

| 1996 | 64.0% 19,755 | 23.3% 7,178 |

| 1992 | 55.3% 19,510 | 24.6% 8,660 |

Voter registration

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of March 3, 2020[104] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 34,681 | 57.38% | |||

| Unenrolled | 16,205 | 26.81% | |||

| Republican | 6,883 | 11.39% | |||

| Green Independent | 2,674 | 4.42% | |||

| Total | 60,443 | 100% | |||

Infrastructure

Fire department

The Portland Fire Department (PFD) provides fire protection and emergency medical services to the city of Portland 24/7, 365. Established on March 29, 1768, the PFD is made up of over 230 paid, professional firefighters and operates out of 7 Fire Stations, located throughout the city, in addition to Fire Stations staffed by "on-call" firefighters on Peaks Island; Great Diamond Island; Cushing Island; and Cliff Island. The Portland Fire Department also operates an Airport Division Station at 1001 Westbrook St., at the Portland International Jetport, and a Marine Division Station, located at 54 Commercial St.[105][106] The PFD operates a 4 Platoon shift schedule. Each platoon works for 24 hours followed by one day off. They then work another 24 hour shift followed by 5 days off. The cycle then repeats.

The Portland Fire Department operates a fire apparatus fleet of 5 Engine Companies; 4 Ladder Companies (including 3 Quints); 1 Rescue Company; 1 Hazardous Materials (Haz-Mat.) Unit; 1 Confined-Space Rescue Unit; 5 ARFF Crash Rescue Units; 3 Marine Units (Fireboats); 5 MEDCU Units (Ambulances); and numerous special, support, and reserve units. Island "call" firefighters man a total of 4 Engines, 1 Ladder, 4 Water Tank Units, and 3 MEDCU Units (Ambulances).

Each frontline fire company is staffed by 1 Officer and 2 Firefighters each shift. Each MEDCU Unit (Ambulance) is staffed by 2 Firefighters (1 Paramedic and 1 AEMT) each shift. The Marine Division is staffed by 1 Officer and 2 Firefighters each shift, who also cross-staff Engine 37 in the event of a structural fire in the city not requiring a Marine Unit. Each platoon has an on duty Deputy Chief, Car 32, who is responsible for day-to-day operations of the shift.

The firefighters are members of IAFF Local 740.

Police

The Portland Police Department is the largest municipal police department in the state of Maine.

Education

High schools

- Baxter Academy for Technology and Science (charter)

- Casco Bay High School (public-expeditionary)

- Cheverus High School (private)

- Deering High School (public)

- Portland Arts & Technology High School (public-vocational)

- Portland High School (public)

- Waynflete School (private)

Colleges and universities

Hospitals

Maine Medical Center is the state's only Level I trauma center and is the largest hospital in Maine.

Mercy Hospital, a faith-based institution, is the fourth largest in the state. It completed the first phase of its new campus along the Fore River in 2008.[107]

The formerly-independent Brighton Medical Center (once known as the Osteopathic Hospital) is now owned by Maine Medical Center and is operated as a minor care center under the names Brighton First Care and New England Rehab. In 2010, Maine Medical Center's Hannaford Center for Safety, Innovation, and Simulation opened at the Brighton campus.[108] The former Portland General Hospital is now home to the Barron Center nursing facility.

Wastewater management

The city of Portland is strongly linked to the sea and other water sources based on its location and the way the urban environment was mapped out. Therefore, the Water Management of the city has taken great pride in the work they are doing to maintain the cleanliness of the water and the management of storm water.

Currently, Wastewater Management umbrellas several divisions: sewer, environmental, administration, and inspection. These programs manage 200 plus miles of sewer lines and 100 plus miles of storm water lines, all playing a role in maintaining sanitary water throughout the City of Portland. The following image shows the different project locations that are currently happening throughout the city.

One of these projects is named the Bedford Street Sewer Separation, with its goal to "improve the water quality and health of Back Cove by reducing the amount of combined sewer overflows (CSO) that over flow during heavy rain events through the use of sewer separation and water treatment devices."[109]

Combined sewer overflows contain untreated or only partially treated waste, toxic materials and debris from industry and people. CSO's are a priority across the United States for urban areas that have Combined Sewer Systems.[110] Chicago is another example of a city that is looking for solutions to the extreme CSO that occur during surges of storms which in turn contaminates the Chicago River.[111]

In Portland there are two phases to this project that will essentially remove 54 acres of drainage from the combined sewer that will instead become separate. Additionally this project includes a transition from strictly "gray infrastructure" to include the implementation of six new "green infrastructure" rain garden areas. Green infrastructure is a tool that allows urban planners to approach and facilitate a transition to sustainable urban environments.[112] Green infrastructure supports the creation and maintenance of conditions that humans and nature can exist in productive harmony to support the well-being of both the natural world and the urban world.

Transportation

Roads

Portland is accessible from I-95 (the Maine Turnpike), I-295, and US 1. U.S. Route 302, a major travel route and scenic highway between Maine and Vermont, has its eastern terminus in Portland. State Routes include SR 9, SR 22, SR 25, SR 26, SR 77, and SR 100. SR 25 Business goes through southwestern Portland.

Intercity buses and trains

Amtrak's Downeaster service offers five daily trains connecting the city with eight towns and cities to the south, ending at Boston's North Station. Trains, with the exception of one weekend trip, also go north to Freeport and Brunswick.

Concord Coach Lines bus service connects Portland to 14 other communities in Maine as well as to Boston's South Station and Logan Airport. Both the Downeaster and the Concord Coach Lines can be found at the Portland Transportation Center on Thompsons Point Road, in the Libbytown neighborhood.[28] Greyhound Lines on Saint John Street connects to 17 Maine communities and to more than 3,600 U.S. destinations.

A carsharing service provided by Uhaul Car Share is available. Both Uber and Lyft operate here. The city bus service is provided by Greater Portland Metro.[113]

Airports

Commercial air service is available at the Portland International Jetport, located in Stroudwater, west of the city's downtown district. American, Southwest, JetBlue, Delta, and United Airlines service the airport. Direct flights are available to Atlanta, Baltimore, Charlotte, Chicago, Detroit, Philadelphia, New York, Newark, Sarasota, and Washington D.C.[114]

Water transportation

The Port of Portland is the second-largest cruise and passenger destination in the state (next to Bar Harbor) and is served by the Ocean Gateway International Marine Passenger Terminal. Ferry service is available year-round to many destinations in Casco Bay. From 2006 to 2009, Bay Ferries operated a high speed ferry called The Cat featuring a five-hour trip to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, for summer passengers and cars. In years past the Scotia Prince Cruises trip took eleven hours. A proposal to replace the defunct Nova Scotia ferry service was rejected in 2013 by the province. From May 15, 2014, until October 2015, the cruise ship ferry Nova Star made daily trips to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia.[115] Due to poor passenger numbers and financial problems, Nova Scotia selected Bay Ferries, the prior operator of The Cat, to operate the service starting in 2016, citing the company's experience and industry relationships. Nova Star officials pledged a smooth transition to the new operator.[116] The Nova Star was later ordered seized by federal marshals for nonpayment of bills.[117]

Bay Ferries announced on March 24, 2016, the charter of the former Hawaii Superferry boat HST-2 from the US Navy for the Portland-Yarmouth service for two years. Bay Ferries signed a 10-year deal with Nova Scotia to run the ferry route, which will take about five and a half hours each way. They stated that the boat would be renamed The Cat[118] and that service would begin around June 15, after refitting in South Carolina. There is still a dispute as to whether the ferry will be permitted to carry trucks, desired by Nova Scotia businesses but opposed by the City of Portland.[119]

The Casco Bay Lines operate several passenger ferries with dozens of trips every day year-round to the major populated islands of Casco Bay. The service to Peaks Island also provides an auto ferry for most of its schedule.

Honors

Food and drink

- Winner, 2018 Restaurant City of the Year by Bon Appetit magazine.

- Ranked as Bon Appétit magazine's "America's Foodiest Small Town" (2009).[120]

- Ranked fourth on Sperlings Best Places list for America's Foodie Cities.[121]

- Named "Best American City for Food" by the Daily Meal (April 2015).[122]

- Named "No. 1 city in U.S. for beer drinkers" by personal finance technology company, SmartAsset (December 2015).[123]

- Ranked first city in the world (April 2016) for craft beer by the largest independent travel publisher in the world, The Matador Network.[124]

- Ranked number 10 in the "VegNews" 12 Best Towns for Vegan Living.[125]

Lifestyle and travel

- Made Foder's 2020 list for top 52 cities in the world for a travel destination.

- Ranked top city in America to spend the weekend (with population under 90,000) by Thrillist.com (May 2018).

- Ranked twelfth on Frommer's 2007 "Top Travel Destinations".[126]

- Named "Best Adventure Town in the East" by Outside Magazine.[127]

Other

- Ranked as Forbes magazine's "Top City for Empty Nesters" (2012).[128] "Top City for Empty Nesters" (Kiplingers)

- Ranked first on Forbes.com "America's Most Livable Cities" (2009).[129]

- Ranked thirteenth on Men's Health Magazine's list of America's 100 most "car crazed" cities.[130]

- Ranked twentieth on the list of Top 20 Best Small Cities for College Students by the American Institute for Economic Research.[131]

- Named one of the "Coolest Small Cities in America" by GQ magazine.[132]

- Ranked as the third gayest city in the nation by UCLA's Williams Institute.[133]

- Ranked third on Men's Journal's list, "The 10 Best Places to Live Now". (2015)[64]

- Ranked fifth on Jetsetter's list, "America's Coolest Small Towns". (2015)[64]

Sister cities

Portland has four sister cities, as designated by Sister Cities International (SCI):

See also

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Official records for Portland were kept at downtown from March 1871 to 24 November 1940, and at Portland Int'l Jetport (PWM) since 25 November 1940. Temperature records are limited to the period that PWM was the official site (i.e. since 1940) and are based on the Monthly Weather Summary product issued by the NWS office in Gray, Maine.<ref name='NWS Gray/Portland, ME Monthly Weather summaries'> "Observed Weather Reports". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

References

- General

- Specific

- Coolidge, A. J. and J. B. Mansfeld (1859). A History and Description of New England, General and Local. Boston: Austin J. Coolidge, p. 301.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "CPH-T-5. Population Change for Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas in the United States and Puerto Rico (February 2013 Delineations): 2000 to 2010" (PDF). census.gov. United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 25, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "Explore Downtown". Portland Downtown. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "Facts and Links | City of Portland". asp.portlandmaine.gov. Archived from the original on January 16, 2017. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Portland History". www.naosmm.org. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013. Retrieved October 9, 2018.

- "portland". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- History of Portland, Maine, Maine Resource Guide, archived from the original on January 31, 2013

- "Portland: The Town that was Almost Boston". Portland Oregon Visitors Association. Archived from the original on July 27, 2013. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- Baxter, James Phinney (September 10, 1893). Christopher Levett, of York: The Pioneer Colonist in Casco Bay. Gorges Society. Retrieved September 10, 2017 – via Internet Archive.

christopher levett.

- "Jedediah Preble letter on Mowat kidnapping, 1775". Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 1, 2007.

- Maine Secretary of State (1899). Private and Special Laws of the State of Maine. Kennebec Journal Print. pp. 9–13. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- Conforti, Joseph (2007). Creating Portland. UPNE. p. xvii. ISBN 978-1-58465-449-0. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- "Bayside is a journey of many 'next steps'". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). October 16, 2006. Archived from the original on October 22, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- Bouchard, Kelley (October 6, 2006). "Riverwalk: Parking garage due to rise; luxury condos to follow". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). Retrieved November 13, 2006.

- Turkel, Tux (February 6, 2007). "An urban vision rises in Bayside". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved February 27, 2007.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on August 5, 2019. Retrieved May 22, 2020.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 2, 2012. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- "Station Name: ME PORTLAND INTL JETPORT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 12, 2016.

- "NOAA". NOAA.

- "Portland, Maine, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- "Neighborhoods". Portland, Maine. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved January 31, 2018.

- "Neighborhoods Associations - Portland, ME". www.livinginportland.org. Archived from the original on January 5, 2014. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Shall We Tax the Hunters?". Lewiston Evening Journal. February 2, 1899. p. 2.

- Deans, Emma (July 8, 2010). "Welcome to Nowhere | Reconnecting an amputated neighborhood". The Bollard. Archived from the original on July 31, 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- #OnPointListens: Listening To A Changing Portland, And Country Archived August 19, 2019, at the Wayback Machine WBUR, August 4, 2017

- Rental Prices Skyrocketing in Portland, Maine NECN, June 23, 2015

- United States Census Bureau. "Census of Population and Housing". Retrieved November 4, 2014.

- "Minor Civil Division Population Search Results". University of Maine. Archived from the original on September 29, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 23, 2012.

- "Maine - Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012.

- "Where School Is In". September 12, 2011. Archived from the original on October 14, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2012 (CBSA-EST2012-01)". 2012 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. September 18, 2013. Archived from the original (CSV) on April 1, 2013. Retrieved September 18, 2013.

- "Portland, Maine". City Data. 2010. Retrieved April 3, 2010.

- "Population estimates, July 1, 2015, (V2015)". www.census.gov. Archived from the original on October 28, 2016. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Portland, Maine Population: Census 2010". www.census.gov. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970 to 1990, For Large Cities And Other Urban Places In The United States" (PDF). US Census Bureau.

- "Poland Spring to ship water by train to Massachusetts distributors". Press Herald. April 6, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2018.

- Bureau of Labor Statistics, June 2017

- https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/01/28/northeastern-university-launches-100-million-research-center-maine

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 124, quoting Edward C. Kirkland. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- Kayorie, James Stephen Merritt (2019). "John Neal (1793-1876)". In Baumgartner, Jody C. (ed.). American Political Humor: Masters of Satire and Their Impact on U.S. Policy and Culture. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 87. ISBN 9781440854866.

- Sears, Donald A. (1978). John Neal. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. p. 123. ISBN 080-5-7723-08.

- "Thompson's Point - Development in Portland, Maine". Thompson's Point. Retrieved January 30, 2017.

- "Pesticide bans raise question: Can we manage garden pests without chemicals?". June 17, 2018.

- "Portland's tough new ban on synthetic pesticides allows few exceptions". January 4, 2018.

- "Franklin Towers". Emporis.com. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- CB Richard Ellis/The Boulos Company. "Greater Portland Area 2006 Office Market Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on August 22, 2006. Retrieved August 10, 2006.

- Bob Keyes (April 4, 2010). "THAT '70S SHOW: A new photography exhibition offers a look back at a very different Portland". Maine Sunday Telegram. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

"Seeing Portland" focuses on the work of photographers from the 1970s and early '80s, including "Splendid Restaurant, Congress Street, Portland, 8/20/76" by Todd Webb. The show opens Saturday at Zero Station in Portland. ... The exhibition brings together the work of several accomplished photographers. In addition to Graham, photographers with work in the show include Tom Brennan, C.C. Church, Rose Marasco, Joe Muir, Mark Rockwood, Jeff Stevensen, Jay York and Todd Webb.

- Bob Keyes (May 30, 2010). "Photographer's estate updates, improves website". Maine Sunday Telegram. Retrieved October 10, 2010.

The estate of Todd Webb announced a recent refurbishment of its website, toddwebbphotographs.com.

- "The 10 Best Portland Restaurants 2017 - TripAdvisor". www.tripadvisor.com. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Callaghan, Adam H. (February 12, 2015). "Back Bay Grill Owner Larry Matthews Returns to Trenches After Graham Botto's Departure". Eater Maine. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- First, Devra (May 9, 2019). "Where to eat and what to order in Portland, Maine - The Boston Globe". BostonGlobe.com. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- "Snack attack: Where to find food trucks and carts in Greater Portland". Press Herald. May 19, 2019. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Goad, Meredith (September 18, 2009). "A second course of food glory". Portland Press Herald. Archived from the original on September 22, 2009. Retrieved September 25, 2009.

- Knowlton, Andrew. "Portland, Maine: In the Magazine: Bon Appétit". Bonappetit.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- Goad, Meredith (April 5, 2007). "Food could put Portland on the map". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers). Archived from the original on October 9, 2007. Retrieved April 5, 2007.

- Goad, Meredith (April 11, 2007). "Where chefs come to shine". Portland Press Herald (Blethen Maine Newspapers, Inc.). Archived from the original on December 26, 2007. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- First, Devra (February 13, 2008). "James Beard Awards: and the nominees might be". The Boston Globe.

- "Zagat". www.zagat.com. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- "A list of lists praising Portland". The Portland Press Herald. November 15, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- "17 of the world's best cities for craft beer". Matador Network. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (December 22, 2019). "Vegan Kitchen: 2019 saw much vegan progress, globally and locally". Press Herald. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- "The Best Cities for Vegans in America". Rent Blog. November 26, 2019. Archived from the original on December 30, 2019. Retrieved December 30, 2019.

- "12 Best Towns for Vegan Living".

- Field, Hayden (October 23, 2015). "10 Great American Cities for Vegans Slideshow". The Daily Meal. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- "Portland, Maine". Food Network. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Writer, Meredith GoadStaff (July 6, 2010). "Man v. Food eats Maine". Press Herald. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Gavin, Ryan. "Watch: That Time When Anthony Bourdain Traveled to Maine & Loved Vacationland on 'No Reservations'". Q97.9. Retrieved January 2, 2019.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (August 2, 2017). "Explosion of smoothies in Portland looks like healthy trend". Press Herald. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Valigra, Lori (May 30, 2016). "Watch out craft brewing: Maine craft coffee is a multimillion-dollar industry". MaineBiz. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- "Tastings, Beer, Wine & Spirits". Visit Portland.

- "Maine Distillers Guild | Make Mine from Maine". Maine Distillers Guild. Retrieved April 1, 2020.

- Graham, Gillian (November 27, 2019). "Exactly 150 years after Sebago Lake water arrived in Portland, focus is still on keeping it clean". Press Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (July 19, 2020). "Vegan Kitchen: Mirror, mirror on the wall, who's the veganist city of all?". Press Herald. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (January 19, 2020). "Vegan Kitchen: Portland's vegan restaurant scene is red-hot". Press Herald. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- Goad, Meredith (August 7, 2018). "Portland food scene's in the big time now with selection as Bon Appetit's Restaurant City of the Year". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved May 18, 2020.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (June 11, 2014). "'Mashup' back for new season of vegan goodness". Press Herald. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- Fotiades, Anestes (August 19, 2009). "Natural Foodie - General News". Portland Food Map. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- Han, Cindy. "Vegan & Plant-Based Living". www.mainepublic.org. Retrieved January 3, 2020.

- Mills, Lindsey (August 26, 2019). "Portland elementary schools to add vegan hot lunch options". News Center Maine. Retrieved September 6, 2019.

- Writer, Aimsel PontiStaff (July 22, 2019). "On the Cheap: Salsa Dancing, Festival of Nations and 'Stand By Me' screening". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- WGME (June 22, 2018). "Greek festival underway in Portland". WGME. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "A complete guide to the best New England fall food festivals | Boston.com". www.boston.com. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- "Proud traditions to highlight the 94th annual St. Peter's Italian Bazaar in Portland". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Atwell, Tom (July 11, 2013). "What Ales You: Brewers' Guild brings craft beer festival to Portland waterfront". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Kamila, Avery Yale (October 27, 2019). "Vegan Kitchen: Some changes are afoot for this year's VegFest". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Writer, Meredith GoadStaff (February 5, 2019). "Taste of Nation dinner to fight childhood hunger returns to Portland". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Writer, Ray RouthierStaff (February 24, 2020). "Nibble and sip your way through Maine Restaurant Week". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Writer, Meredith GoadStaff (February 26, 2020). "The Wrap: New restaurants in the works, and a peek at Seaweed Week". Press Herald. Retrieved April 22, 2020.

- Eschner, Kat. "Why Was Maine the First State to Try Prohibition?". Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "Maine Memory Network Exhibit - Canning: A Maine Industry". www.mainememory.net. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "Civil War Canning Pioneer Winslow's Cannery / Union Army Contractors". www.mainelegacy.com. Retrieved March 27, 2020.

- "History Hoagie Sandwich, History Submarine Sandwich, History Po' Boys Sandwich, Poor Boy Sandwich, History Dagwood Sandwich, History Italian Sandwich". Whatscookingamerica.net. Retrieved April 28, 2013.

- McCanna, Ben (May 14, 2017). "Take a look inside the 150-year-old B&M Beans factory in Portland". Press Herald. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "City of Portland Code of Ordinances, Charter Rev. 7-01-09" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Portland Elected Mayor Measure Passes". Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Copyrighted" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Koenig, Seth (November 6, 2013). "Portland police chief, Maine attorney general say Portland pot legalization vote won't change enforcement strategies". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- "Elections: Data and Information". Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "REGISTERED & ENROLLED VOTERS - STATEWIDE" (PDF). March 3, 2020.

- "Fire Department - Portland, ME". portlandmaine.gov. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Portland, ME". portlandmaine.gov. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Archived December 23, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Hannaford Center Safety Innovation & Simulation". simulation.mmc.org.

- "Bedford Street Sewer Separation Project | Portland, ME". www.portlandmaine.gov. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- "Combined Sewer Overflows (CSOs)". US EPA. October 13, 2015. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- Hawthorne, Michael. "Chicago River still teems with bacteria flushed from sewers after storms". chicagotribune.com. Retrieved November 20, 2019.

- "Multiple benefits of green infrastructure and role of green infrastructure in sustainability and ecosystem services". Minnesota Stormwater Manual.

- "METRO Bus - Portland, ME". www.portlandmaine.gov. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- http://www.transtats.bts.gov/airports.asp?pn=1&Airport=PWM&Airport_Name=Portland,%20ME:%20Portland%20International%20%20Jetport&carrier=FACTS

- Richardson, Whit (March 5, 2013). "Nova Scotia rejects both proposals to restart ferry service to Maine". Bangor Daily News. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- Fischell, Darren (October 29, 2015). "Province prefers past Cat ferry operator over Nova Star for 2016". Bangordailynews.com. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- Betts, Stephen (October 31, 2015). "Court orders seizure of Nova Star ferry". Bangordailynews.com. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- Murphy, Edward (March 24, 2016). "New ferry expected to make Portland-Yarmouth trip in 51⁄2 hours". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- Fischell, Darren (March 24, 2016). "Ferry operator lands ship, signs 10-year Portland-Nova Scotia deal". Bangordailynews.com. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- "America's Foodiest Small Town". Archived from the original on August 27, 2013.

- Ethridge, Will (January 31, 2011). "America's Top Foodie Cities – Portland is #4!". Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Best American Cities for Food". The Daily Meal. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- "The Best Cities for Beer Drinkers | SmartAsset.com". smartasset.com. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- "17 of the world's best cities for craft beer". Matador Network. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- "12 Best Towns for Vegan Living". Retrieved December 27, 2017.

- "Frommer's Top Travel Destinations for 2007". Frommer's (Wiley Publishing, Inc.). November 21, 2006. Archived from the original on February 27, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2006.

- "Portland, Maine: Best. City. Ever". Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- "Second Act". Archived from the original on November 23, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2012.

- "America's Most Livable Cities". Forbes. April 1, 2009. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2009.

- "America's Most Car-Crazed Cities". Archived from the original on February 3, 2015. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- Quimby, Beth (September 10, 2010). "Portland joins list of top college cities". Portland Press Herald. Retrieved September 10, 2010.

- "The Coolest Small Cities in America". GQ. Retrieved November 6, 2010.

- "Yep, We're Gay! Study Finds Portland (Maine!) Third Gayest City". LiveWorkPortland. July 25, 2010. Archived from the original on May 21, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2011.

- "Japan index of Sister Cities International retrieved on December 9, 2008". Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

Further reading

- John F. Bauman. Gateway to Vacationland: The Making of Portland Maine (University of Massachusetts Press: 2012) 285 pages; Explores the socio-economic, political and cultural history of Portland emphasizing the evolution of the city's built environment after the fire of 1866.

- Michael C. Connolly. Seated by the Sea: The Maritime History of Portland, Maine, and Its Irish Longshoremen (University Press of Florida; 2010) 280 pages; Focuses on the years 1880 to 1923 in a study of how an influx of Irish immigrant workers transformed the city's waterfront.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Portland, Maine. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Portland, Maine. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Portland, Maine. |

- Official website

- Port of Portland

- Portland Public Schools

- Portland Public Library

- Portland's Downtown District

- Greater Portland Casco Bay Convention and Visitors Bureau

- Old USGS maps of Portland Area.

- 1876 Panoramic Birdseye View of Portland by Warner at LOC.

- Guide to the Western Promenade, Portland, Maine, Portlandlandmarks.org