Virginia Beach, Virginia

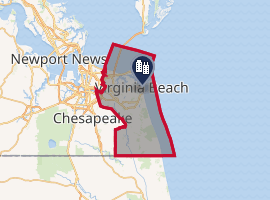

Virginia Beach is an independent city located on the southeastern coast of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 437,994;[5] in 2019, it was estimated to be 449,974.[2] Although mostly suburban in character, it is the most populous city in Virginia and the 44th most populous city in the nation.[6] Located on the Atlantic Ocean at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, Virginia Beach is included in the Hampton Roads metropolitan area. This area, known as "America's First Region", also includes the independent cities of Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, and Suffolk, as well as other smaller cities, counties, and towns of Hampton Roads.

Virginia Beach, Virginia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City of Virginia Beach | |||

Virginia Beach from the pier | |||

Flag  Seal | |||

| Nickname(s): "The Resort City", "Neptune City" | |||

| Motto(s): Landmarks of Our Nation's Beginning | |||

Virginia Beach, Virginia  Virginia Beach, Virginia | |||

| Coordinates: 36°51′00″N 75°58′40″W | |||

| Country | |||

| State | |||

| County | None (Independent city) | ||

| Incorporated (as town) | 1906 | ||

| Incorporated (as city) | 1952 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Council-manager | ||

| • Mayor | Bobby Dyer (R) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Independent city | 497.50 sq mi (1,288.52 km2) | ||

| • Land | 244.72 sq mi (633.83 km2) | ||

| • Water | 252.78 sq mi (654.69 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 10 ft (3 m) | ||

| Population (2010) | |||

| • Independent city | 437,994 | ||

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 449,974 | ||

| • Rank | US: 44th VA: 1st | ||

| • Density | 1,838.71/sq mi (709.93/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 1,212,000 | ||

| • Metro | 1,725,246 (37th) | ||

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (EST) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) | ||

| Area code(s) | 757, 948 (planned) | ||

| FIPS code | 51-82000[3] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1500261[4] | ||

| Website | Official website | ||

| |||

Virginia Beach is a resort city with miles of beaches and hundreds of hotels, motels, and restaurants along its oceanfront. Every year the city hosts the East Coast Surfing Championships as well as the North American Sand Soccer Championship, a beach soccer tournament. It is also home to several state parks, several long-protected beach areas, three military bases, a number of large corporations, Virginia Wesleyan University and Regent University, the international headquarters and site of the television broadcast studios for Pat Robertson's Christian Broadcasting Network (CBN), Edgar Cayce's Association for Research and Enlightenment, and numerous historic sites. Near the point where the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean meet, Cape Henry was the site of the first landing of the English colonists, who eventually settled in Jamestown, on April 26, 1607.

The city is listed in the Guinness Book of Records as having the longest pleasure beach in the world. It is located at the southern end of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel, the longest bridge-tunnel complex in the world.[7]

History

The Chesepian were the historic indigenous people of the area now known as Tidewater in Virginia at the time of European encounter. Little is known about them[8] but archeological evidence suggests they may have been related to the Carolina Algonquian, or Pamlico people. They would have spoken one of the Algonquian languages. These were common among the numerous tribes of the coastal area, who made up the loose Powhatan Confederacy, numbering in the tens of thousands in population. The Chesepian occupied an area which is now defined as the independent cities of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Chesapeake, and Virginia Beach.[9]

In 1607, after a voyage of 144 days, three ships headed by Captain Christopher Newport, and carrying 105 men and boys, made their first landfall in the New World on the mainland, where the southern mouth of the Chesapeake Bay meets the Atlantic Ocean. They named it Cape Henry, after Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King James I of England. These English colonists of the Virginia Company of London moved on from this area, as they were under orders to seek a site further inland, which would be more sheltered from ships of competing European countries. They created their first permanent settlement on the north side of the James River at Jamestown.[10]

Adam Thoroughgood (1604–1640) of King's Lynn, Norfolk, England is one of the earliest Englishmen to settle in this area, which was developed as Virginia Beach. At the age of 18, he had contracted as an indentured servant to pay for passage to the Virginia Colony in the hopes of bettering his life. He earned his freedom after several years and became a leading citizen of the area. In 1629, he was elected to the House of Burgesses for Elizabeth Cittie [sic], one of four "citties" (or incorporations) which were subdivided areas established in 1619.[11]

In 1634, the Colony was divided into the original eight shires of Virginia, soon renamed as counties. Thoroughgood is credited with using the name of his home in England when helping name "New Norfolk County" in 1637. The following year, New Norfolk County was split into Upper Norfolk County (soon renamed Nansemond County) and Lower Norfolk County. Thoroughgood resided after 1634 was along the Lynnhaven River, named for his home in England.

Lower Norfolk County was large when first organized, defined as from the Atlantic Ocean west past the Elizabeth River, encompassing the entire area now within the modern cities of Portsmouth, Norfolk, Chesapeake, and Virginia Beach.[11] It attracted many entrepreneurs, including William Moseley with his family in 1648. Belonging to the Merchant Adventurers Guild of London, he immigrated from Rotterdam of the Netherlands, where he had been in the international trade. He settled on land on the north side of the Elizabeth River, east of what developed as Norfolk.

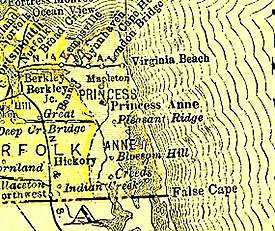

Following increased settlement, in 1691 Lower Norfolk County was divided to form Norfolk and Princess Anne counties. Princess Anne, the easternmost county in South Hampton Roads, extended from Cape Henry at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, south to what became the border of the North Carolina colony. It included all of the area fronting the Atlantic Ocean. Princess Anne County was known as a jurisdiction from 1691 to 1963, over 250 years.[12]

In the early centuries, this area was rural and developed for plantation agriculture. In the late 19th century, the small resort area of Virginia Beach developed in Princess Anne County after the 1883 arrival of rail service to the coast. The Virginia Beach Hotel was opened and operated by the Norfolk and Virginia Beach Railroad and Improvement Company at the oceanfront, near the tiny community of Seatack. The hotel was foreclosed and the railroad reorganized in 1887. The hotel was upgraded and reopened in 1888 as the Princess Anne Hotel.[13]

In 1891, guests at the new hotel watched the wreck and rescue efforts of the United States Life-Saving Service for the Norwegian bark Dictator. The ship's figurehead, which washed up on the beach several days later, was erected as a monument to the victims and rescuers. It stood along the oceanfront for more than 50 years. In the 21st century, it inspired the pair of matching Norwegian Lady Monuments, sculpted by Ørnulf Bast and installed in Virginia Beach and Moss, Norway.[14]

The resort initially depended on railroad and electric trolley service. The completion of Virginia Beach Boulevard in 1922, which extended from Norfolk to the oceanfront, opened the route for automobiles, buses, and trucks. The passenger rail service to the oceanfront was eventually discontinued as traffic increased by vehicle. The growing resort of Virginia Beach became an incorporated town in 1906. Over the next 45 years, Virginia Beach continued to grow in popularity as a seasonal vacation spot. The casinos were replaced by amusement parks and family-oriented attractions. In 1927 The Cavalier Hotel opened and became a popular vacation spot.

Virginia Beach gained status as an independent city in 1952, although ties remained between it and Princess Anne County. In 1963, after voters in the two jurisdictions passed a supporting referendum, and with the approval of the Virginia General Assembly, the two political subdivisions were consolidated as a new, much larger independent city, retaining the better-known name of the Virginia Beach resort.[15]

The Alan B. Shepard Civic Center ("The Dome"), a significant building in the city's history, was constructed in 1958,[16] and was dedicated to the career of former Virginia Beach resident and astronaut Alan Shepard.[17] As the area changed, the Dome was frequently used as a bingo hall. The building was razed in 1994[16] to make room for a municipal parking lot and potential future development.

Recent history

Real estate, defense, and tourism are major sectors of the Virginia Beach economy. Local public and private groups have maintained a vested interest in real-estate redevelopment, resulting in a number of joint public-private projects, such as commercial parks. Examples of the public-private development include the Virginia Beach Convention Center, the Oceanfront Hilton Hotel, and the Virginia Beach Town Center. The city assisted in financing the project through the use of tax increment financing: creating special tax districts and constructing associated street and infrastructure to support the developments. The Town Center opened in 2003, with related construction continuing. The Convention Center opened in 2005.[18][19]

The city has begun to run out of clear land available for new construction north of the Green Line, an urban growth boundary dividing the urban northern and rural southern sections of the city.[20] Infill and development of residential neighborhoods has placed a number of operating constraints on Naval Air Station Oceana, a major fighter jet base for the U.S. Navy. While the airbase enjoys wide support from Virginia Beach at large, the Pentagon Base Realignment and Closure commission has proposed closure of Oceana within the next decade.[21]

This land crunch led to floodplain development. During Hurricane Matthew, the heavy rainfall flooded over 2000 homes and left some neighborhoods with standing water for days. Given the rising risks of flooding due to climate change and the impetus of the hurricane damage, the city rejected several further development proposals. This rejection was significant from two perspectives. First, cities reject building very rarely, demonstrating the shift in public perception. Second, these rejections led to lawsuits by the developers. The rejection of these lawsuits in the courts provides precedent for other sorts of local climate change adaptation efforts in the future. Discussing the matter, Mayor Dryer noted, "It’s a confrontation with reality. Not everybody’s going to be happy.”[22]

On May 31, 2019, a mass shooting occurred at a municipal government building in Virginia Beach. A former employee entered the building and shot indiscriminately, killing 12 people and injuring 4 before dying from a gunshot wound from the police.[23]

Geography

Virginia Beach is located at 36.8506°N 75.9779°W.[24]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 497 square miles (1,290 km2), of which 249 square miles (640 km2) is land and 248 square miles (640 km2) (49.9%) is water.[24] It is the largest city in Virginia by total area and third-largest city land area. The average elevation is 12 feet (3.7 m) above sea level. A major portion of the city drains to the Chesapeake Bay by way of the Lynnhaven River and its tributaries.

The city is located at the southeastern corner of Virginia in the Hampton Roads area bordering the Atlantic Ocean. The Hampton Roads Metropolitan Statistical Area (officially known as the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA) is the 37th largest in the United States, with a total population of 1,707,639. The area includes the Virginia cities of Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Poquoson, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Williamsburg, and the counties of Gloucester, Isle of Wight, James City, Mathews, Surry, and York, as well as the North Carolina county of Currituck. While Virginia Beach is the most populated city within the MSA, it actually currently functions more as a suburb. The city of Norfolk is recognized as the central business district, while the Virginia Beach oceanside resort district and Williamsburg are primarily centers of tourism.

Neighborhoods

When the modern city of Virginia Beach was created in 1963, by the consolidation of the 253 square miles (660 km2) Princess Anne County with the 2 square miles (5.2 km2) City of Virginia Beach, the newly larger city was divided into seven boroughs: Bayside, Blackwater, Kempsville, Lynnhaven, Princess Anne, Pungo, and Virginia Beach.

Virginia Beach has many distinctive communities and neighborhoods within its boundaries, including: Alanton, Aragona Village, the largest sub-division in Tidewater when completed, Bay Colony, Bayside, Cape Henry, Chesapeake Beach, Croatan Beach, Great Neck Point, Green Run, Kempsville, Lago Mar, London Bridge, Lynnhaven, Newtown, The North End, Oceana, Ocean Park, Pembroke Manor, Princess Anne, Pungo, Red Mill Commons, Sandbridge, Thalia, and Thoroughgood.[25]

Climate

| Virginia Beach, VA[26] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The climate of Virginia Beach is humid subtropical (Köppen: Cfa). For the Trewartha update system the climate is the northern limit of Cf (subtropical) which corresponds to the ecology of the area, which struggles to withstand the cooler temperatures further north or inland.[27][28]

Winters are cool and snowfall is light. Summers are hot and humid. The official weather statistics are recorded at Norfolk International Airport on the extreme northwestern border of Virginia Beach. The mean annual temperature is 59.6 °F (15.3 °C), with an average annual snowfall of 5.8 inches (150 mm) at the airport to around 3.0 inches (76 mm) in the southeastern corner around Back Bay.[29] Average annual precipitation (the large majority rainfall) is high, ranging between 47 inches (1,200 mm) at the airport to over 50 inches (1,300 mm) per year at Back Bay. The wettest season is summer, specifically July to early September, with August the single wettest month, averaging over 5.5 inches of rain. From October to June, average monthly precipitation is remarkably consistent, ranging between 3.1 and 3.7 inches. The highest recorded temperature to date was 105 °F (41 °C) in July 2010, and the lowest recorded temperature was −3 °F (−19 °C) in January 1985, both being recorded at Norfolk International Airport.[30]

Additionally, the geographic location of the city, with respect to the principal storm tracks, is especially favorable which is why it has earned the reputation as a vacation destination. It is south of the average path of storms originating in the higher latitudes, and north of the usual tracks of hurricanes and other major tropical storms, with the exception of Hurricane Isabel in 2003.[31] Because of the moderating effects of the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean, Virginia Beach is the northernmost location on the east coast in which many species of plants (both subtropical and tropical) will reliably grow. Spanish moss, for example is near the northernmost limit of its natural range at First Landing State Park, and is the most northerly location where it is widespread. Other plants like Sabal minor, Sabal palmetto, Pindo Palm (in protected locations), and Oleander are successfully grown here while they succumb to the colder winter temperatures to the north and inland to the west.

| Climate data for Norfolk International Airport, Virginia (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1874–present[lower-alpha 2]) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 84 (29) |

82 (28) |

92 (33) |

97 (36) |

100 (38) |

102 (39) |

105 (41) |

105 (41) |

100 (38) |

95 (35) |

86 (30) |

82 (28) |

105 (41) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 71.1 (21.7) |

73.2 (22.9) |

80.2 (26.8) |

86.4 (30.2) |

91.4 (33.0) |

95.5 (35.3) |

97.8 (36.6) |

95.8 (35.4) |

92.1 (33.4) |

85.6 (29.8) |

78.7 (25.9) |

72.5 (22.5) |

98.8 (37.1) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 48.1 (8.9) |

50.9 (10.5) |

58.2 (14.6) |

67.6 (19.8) |

75.4 (24.1) |

83.5 (28.6) |

87.4 (30.8) |

85.1 (29.5) |

79.3 (26.3) |

70.1 (21.2) |

61.1 (16.2) |

52.1 (11.2) |

68.3 (20.2) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 32.7 (0.4) |

34.4 (1.3) |

40.5 (4.7) |

48.9 (9.4) |

57.9 (14.4) |

67.1 (19.5) |

71.9 (22.2) |

70.7 (21.5) |

65.3 (18.5) |

54.0 (12.2) |

44.6 (7.0) |

36.1 (2.3) |

52.1 (11.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 17.6 (−8.0) |

21.2 (−6.0) |

27.2 (−2.7) |

35.7 (2.1) |

45.7 (7.6) |

55.5 (13.1) |

63.1 (17.3) |

61.6 (16.4) |

53.7 (12.1) |

39.7 (4.3) |

30.5 (−0.8) |

21.7 (−5.7) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −3 (−19) |

2 (−17) |

14 (−10) |

23 (−5) |

36 (2) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

49 (9) |

40 (4) |

27 (−3) |

17 (−8) |

5 (−15) |

−3 (−19) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.40 (86) |

3.12 (79) |

3.68 (93) |

3.41 (87) |

3.41 (87) |

4.26 (108) |

5.14 (131) |

5.52 (140) |

4.76 (121) |

3.42 (87) |

3.15 (80) |

3.26 (83) |

46.53 (1,182) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 2.4 (6.1) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

trace | 1.2 (3.0) |

5.8 (15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 10.4 | 9.5 | 10.6 | 10.1 | 10.6 | 9.9 | 11.1 | 10.1 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 117.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 1.6 | 1.3 | 0.4 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 4.0 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66.3 | 65.6 | 64.6 | 62.8 | 68.8 | 70.6 | 73.3 | 75.2 | 74.4 | 72.1 | 68.5 | 67.0 | 69.1 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 27.9 (−2.3) |

28.9 (−1.7) |

35.8 (2.1) |

43.2 (6.2) |

54.5 (12.5) |

63.1 (17.3) |

68.2 (20.1) |

68.0 (20.0) |

62.4 (16.9) |

51.3 (10.7) |

41.7 (5.4) |

32.7 (0.4) |

48.1 (9.0) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 171.5 | 175.2 | 229.3 | 252.8 | 271.7 | 280.1 | 278.3 | 260.4 | 231.4 | 208.3 | 175.7 | 160.4 | 2,695.1 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 56 | 58 | 62 | 64 | 62 | 64 | 62 | 62 | 62 | 60 | 57 | 53 | 61 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 4 | 5 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[30][32][33] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas[34] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

.png)

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1910 | 320 | — | |

| 1920 | 846 | 164.4% | |

| 1930 | 1,719 | 103.2% | |

| 1940 | 2,600 | 51.3% | |

| 1950 | 5,390 | 107.3% | |

| 1960 | 8,091 | 50.1% | |

| 1970 | 172,106 | 2,027.1% | |

| 1980 | 262,199 | 52.3% | |

| 1990 | 393,069 | 49.9% | |

| 2000 | 425,257 | 8.2% | |

| 2010 | 437,994 | 3.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 449,974 | [2] | 2.7% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[35] 1790-1960[36] 1900-1990[37] 1990-2000[38] | |||

| Racial composition | 2010[39] | 1990[40] | 1970[40] | 1950[40] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 67.7% | 80.5% | 90.0% | 95.5% |

| —Non-Hispanic Whites | 64.5% | 78.8% | 88.9%[41] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 19.6% | 13.9% | 9.1% | 4.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 6.6% | 3.1% | 1.3%[41] | (X) |

| Asian | 6.1% | 4.3% | 0.7% | − |

According to the 2010 Census, the racial composition of Virginia Beach was as follows:[39]

- White or Caucasian: 67.7% (Non-Hispanic White: 64.5%)

- Black or African American: 19.6%

- Native American: 0.4%

- Asian: 6.1% (4.0% Filipino, 0.5% Chinese, 0.4% Indian, 0.4% Vietnamese, 0.3% Korean, 0.2% Japanese)

- Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander: 0.1%

- Some other race: 2.0%

- Two or more races: 4.0%

- Hispanic or Latino (of any race): 6.6% (2.2% Puerto Rican, 1.9% Mexican, 0.3% Dominican, 0.2% Panamanian, 0.2% Salvadoran, 0.2% Cuban, 0.2% Colombian)

As of the 2000 Census,[3] there were 425,257 people, 154,455 households, and 110,898 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,712.7 people per square mile (661.3/km²). There were 162,277 housing units at an average density of 653.6 per square mile (252.3/km²).

There were 154,455 households out of which 38.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 55.7% were married couples living together, 12.4% had a female householder with no husband present, and 28.2% were non-families. 20.4% of all households were made up of individuals and 5.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.70 and the average family size was 3.14.

The age distribution was 27.5% under the age of 18, 10.0% from 18 to 24, 34.3% from 25 to 44, 19.8% from 45 to 64, and 8.4% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females, there were 98.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 95.8 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $48,705, and the median income for a family was $53,242. Virginia Beach had the 5th highest median family income among large cities in 2003.[42] The per capita income for the city was $22,365. About 5.1% of families and 8.2%[43][44] of the population were below the poverty line, including 8.6% of those under age 18 and 4.7% of those age 65 or over.

7.1% of the people under the age of 65 years are disabled while 8.6% people don't have health insurance.[44]

The city of Virginia Beach has a lower crime rate than the other regional cities of Hampton Roads, Newport News, Norfolk, and Portsmouth, which all exceed national average crime rates. In 1999 Virginia Beach experienced 12 murders giving the city a murder rate of 2.7 per 100,000 people. For 2007, Virginia Beach had 16 murders, for a murder rate of 3.7 per 100,000 people. That was lower than the national average that year of 6.9. The city's total crime index rate for 2007 was 221.2 per 100,000 people, lower than the national average of 320.9.[45] According to the Congressional Quarterly Press '2008 City Crime Rankings: Crime in Metropolitan America, Virginia Beach, Virginia ranks 311th in violent crime among 385 cities containing more than 75,000 inhabitants.[46]

| Crime | Virginia Beach (2009) | National Average |

|---|---|---|

| Murder | 3.7 | 6.9 |

| Rape | 20.2 | 32.2 |

| Robbery | 127.3 | 195.4 |

| Assault | 98.6 | 340.1 |

| Burglary | 495.2 | 814.5 |

| Automobile Theft | 134.4 | 526.5 |

Religion

34.4% of the city's population is affiliated with religious congregations, compared to the 50.2% nationwide figure. There are 146,402 adherents and 184 different religious congregations in the city.[47]

- 28% Catholic Church

- 14% Southern Baptist Convention

- 13% United Methodist Church

- 12% Charismatic Churches Independent

- 33% Others

Economy

Virginia Beach is composed of a variety of industries, including national and international corporate headquarters, advanced manufacturers, defense contractors and locally-owned businesses. The city's location and business climate have made it a hub of international commerce, as nearly 200 foreign firms have established a presence, an office location or their North American headquarters in Hampton Roads. Twenty internationally-based firms have their U.S. or North American headquarters in Virginia Beach, including companies like Stihl, Busch, IMS Gear, and Sanjo Corte Fino. Other major companies headquartered in Virginia Beach include Amerigroup, the Christian Broadcasting Network and Operation Blessing International. Other major employers include GEICO, VT and Navy Exchange Service Command.[48] Virginia Beach was ranked at number 45 on Forbes list of best places for business and careers.

Tourism produces a large share of Virginia Beach's economy. With an estimated $857 million spent in tourism related industries, 14,900 jobs cater to 2.75 million visitors. City coffers benefit as visitors provide $73 million in revenue. Virginia Beach opened a Convention Center in 2005 which caters to large group meetings and events. Hotels not only line the oceanfront but also cluster around Virginia Beach Town Center and other parts of the city. Restaurants and entertainment industries also directly benefit from Virginia Beach's tourism.[48]

Virginia Beach has a large agribusiness sector which produces $80 million for the city economy. One hundred-seventy-two farms exist in Virginia Beach, mostly below the greenline in the southern portion of the city. Farmers are able to sell their goods and products at the city's Farmer's Market.[49][50]

Virginia Beach is home to several United States Military bases. These include the United States Navy's NAS Oceana and Training Support Center Hampton Roads, and the Joint Expeditionary Base East located at Cape Henry. Additionally, NAB Little Creek is located mostly within the city of Virginia Beach but carries a Norfolk address.[51]

NAS Oceana is the largest employer in Virginia Beach; it was decreed by the 2005 BRAC Commission that NAS Oceana must close unless the city of Virginia Beach condemns houses in areas designated as "Accident Potential Zones." This action has never been the position of the United States Navy; indeed, the Navy had not recommended NAS Oceana to the BRAC Commission for potential closure. The issue of closure of NAS Oceana remains unresolved as of May 2008 [21]

Both NAS Oceana and Training Support Center Hampton Roads are considered to be the largest of their respective kind in the world. Furthermore, located in nearby Norfolk is the central hub of the United States Navy's Atlantic Fleet, Norfolk Navy Base.[52][53]

54% of the 171,000 people working in Virginia Beach live in the city, 12% live in Chesapeake, and 10% live in Norfolk. An additional 99,600 people commute from Virginia Beach, with 35% going to Norfolk and 23% going to Chesapeake. Unemployment has been cut almost in half over the past two years going from a high of 4.2% in January 2017 to 2.8% in June 2019.[54]

Culture

The city is home to several points of interest in the historical, scientific, and visual/performing arts areas, and has become a popular tourist destination in recent years. The Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art features regularly changing exhibitions in a variety of media. Exhibitions feature painting, sculpture, photography, glass, video and other visual media from internationally acclaimed artists as well as artists of national and regional renown. MOCA was born from the annual Boardwalk Art Show, which began in 1952 and is now the museum's largest fundraiser.

The Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center (formerly the Virginia Marine Science Museum) is a popular aquarium near the oceanfront that features various sharks, sting rays, sea turtles, jellyfish, and octopuses.[55]

One of the world's largest collections of World War I and World War II aircraft is located at the Military Aviation Museum in the Pungo area of Virginia Beach.[56]

The Virginia Beach Amphitheater, built in 1996, features a wide variety of popular shows and concerts. The Sandler Center, a 1200-seat performing arts theatre, opened in the Virginia Beach Town Center in November 2007.[57]

Virginia Beach is home to many sites of historical importance and has 18 sites on the National Register of Historic Places. Such sites include the Adam Thoroughgood House (one of the oldest surviving colonial homes in Virginia), the Francis Land House (a 200-year-old plantation), the Cape Henry Lights and nearby Cape Henry Light Station (a second tower), De Witt Cottage, Adam Keeling House, and others.[58]

The Edgar Cayce Hospital for Research and Enlightenment was established in Virginia Beach in 1928 with 60 beds. The 67th street facility features a large private library of books on psychic matters, and is open to the public. The traditional beach-architecture headquarters building features massage therapy by appointment. Cayce opened Atlantic University in 1930; it closed two years later but was re-opened in 1985. Atlantic University was originally intended for study of Cayce's readings and research on spiritual subjects.[59]

The city's largest festival, the Neptune Festival, attracts 500,000 visitors to the oceanfront and 350,000 visitors to the air show at NAS Oceana. Celebrating the city's heritage link with Norway, events are held in September in the oceanfront and Town Center areas.[60] Every August, the American Music Festival provides festival attendees with live music performed on stages all over the oceanfront, including the beach on Fifth Street. The festival ends with the Rock 'n' Roll Half Marathon.[61]

Sports

| Club | League | Venue | Established |

|---|---|---|---|

| Virginia Beach City FC | NPSL Soccer | Virginia Beach Sportsplex | 2014 |

Since Norfolk contains the central business district of Hampton Roads, most of the major spectator sports are located there. While the Hampton Roads area has been recently considered as a viable prospect for major-league professional sports, and regional leaders have attempted to obtain Major League Baseball, NBA and NHL franchises in the recent past, no team has yet relocated to the area.[62] Hampton Roads is the second largest metropolitan area in the United States without a club in a major professional sports league, after the Austin, Texas metropolitan area.

The Norfolk Admirals won the AHL Calder Cup in 2012.

The Virginia Destroyers, a UFL franchise, played at the Virginia Beach Sportsplex until the league's collapse in 2012. Virginia Beach Professional Baseball, LLC, was awarded an Atlantic League franchise in April 2013, the Virginia Beach Neptunes; however it has yet to play a game due to delays in building Wheeler Field. Two soccer teams, the Virginia Beach Piranhas, a men's team in the USL Premier Development League, and the Hampton Roads Piranhas, a women's team in the W-League play at the Virginia Beach Sportsplex. The Virginia Beach Sportsplex contains the central training site for the U.S. women's national field hockey team.

The city is also home to the East Coast Surfing Championships, an annual contest of more than 100 of the world's top professional surfers and an estimated 400 amateur surfers. This is North America's oldest surfing contest.

There are eleven golf courses open to the public in the city, as well as four country club layouts and 36 military holes at NAS Oceana's Aeropines course. Among the best-known public courses are Hell's Point Golf Club and Virginia Beach National, the latter of which hosted the Virginia Beach Open, a Nationwide Tour event from 2000 to 2006.[63] Also, the Kingsmill Resort hosts the Kingsmill Championship, an annual LPGA Tour tournament.

Virginia Beach is host to a Rock 'n' Roll Half Marathon each year on Labor Day weekend in conjunction with the American Music Festival. It is one of the largest Half Marathons in the world. The final 3 miles (4.8 km) are on the boardwalk.[64] Virginia Beach also hosts the Yuengling Shamrock Marathon, founded in 1973 with over 24,000 participants. It is an annual race over St. Patrick’s Day weekend and was recognized by Runner’s World as one of the Top 20 marathons in the country in 1992.[65]

Parks and recreation

Virginia Beach is home to 210 city parks, encompassing over 4,000 acres (1,600 ha), including neighborhood parks, community parks, district parks, and other open spaces.[66]

Mount Trashmore Park is clearly visible from I-264 when traveling to the oceanfront. The hill measures 60 ft (18 m) high and is the highest point in Virginia Beach.[67]

One of the major parks is Red Wing Park, a 97 acres (39 ha) park in east-central part of the city, very close to Oceana Naval Air Station. This land became a park in 1966. A unique feature of this park is the Miyazaki Japanese Garden, which is a result of its interactions with its sister city Miyazaki, Japan.[68]

The Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1938, is an 8,000-acre (32 km2) fresh water refuge that borders the Atlantic Ocean on the east and Back Bay on the west. It is managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.[69]

First Landing State Park and False Cape State Park are both located in coastal areas within the city's corporate limits as well.[70][71]

Pleasure House Point is an 118 acres (48 hectares) park of undeveloped land on the shore of the Lynnhaven River. It is also the location of the Brock Environmental Center.[72]

Virginia Beach's extensive park system is recognized as one of the best in the United States. In its 2013 ParkScore ranking, The Trust for Public Land reported that Virginia Beach had the 8th best park system among the 50 most populous U.S. cities.[73]

Government

Unlike most large independent cities in Virginia, Virginia Beach has consistently backed Republican Party presidential candidates since 1968. However, their margins of victory have diminished in recent years. John McCain and Donald Trump only managed to win a plurality of the city's votes in 2008 and 2016, winning the city despite losing statewide.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third Parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 48.4% 98,224 | 44.8% 91,032 | 6.8% 13,763 |

| 2012 | 50.5% 99,291 | 48.0% 94,299 | 1.6% 3,051 |

| 2008 | 49.9% 100,319 | 49.1% 98,885 | 1.0% 2,045 |

| 2004 | 59.1% 103,752 | 40.2% 70,666 | 0.7% 1,269 |

| 2000 | 55.9% 83,674 | 41.6% 62,268 | 2.6% 3,829 |

| 1996 | 50.6% 63,741 | 41.4% 52,142 | 8.0% 10,060 |

| 1992 | 50.0% 68,936 | 32.2% 44,294 | 17.8% 24,555 |

| 1988 | 68.9% 76,481 | 30.4% 33,780 | 0.7% 757 |

| 1984 | 74.4% 72,571 | 25.3% 24,703 | 0.3% 320 |

| 1980 | 60.5% 47,936 | 31.4% 24,895 | 8.1% 6,404 |

| 1976 | 54.5% 34,593 | 40.7% 25,824 | 4.9% 3,101 |

| 1972 | 76.6% 38,074 | 20.9% 10,373 | 2.6% 1,286 |

| 1968 | 43.2% 16,316 | 26.8% 10,101 | 30.0% 11,325 |

| 1964 | 44.9% 10,529 | 55.0% 12,892 | 0.1% 21 |

| 1960 | 42.5% 986 | 56.1% 1,301 | 1.5% 34 |

| 1956 | 53.3% 1,355 | 43.7% 1,111 | 3.0% 77 |

| 1952 | 59.8% 1,310 | 40.2% 881 |

Virginia Beach was chartered as a municipal corporation by the General Assembly of Virginia on January 1, 1963. The city currently operates under the council–manager form of government.[75] The city does not fall under the jurisdiction of a county government, due to state law. Rather, it functions as an independent city and operates as a political subdivision of the state.

The city's legislative body consists of an eleven-member city council. The city manager is appointed by the council and acts as the chief executive officer. Through his staff, he implements policies established by the council.[76]

Members of the city council normally serve four-year terms and are elected on a staggered basis in non-partisan elections. Beginning in 2008, general elections are held the first Tuesday in November in even-numbered years. In previous years, elections were held the first Tuesday in May in even-numbered years. All registered voters are eligible to vote for all council members. Three council members and the mayor serve on an at-large basis. All others are elected by district (and must live in the district they represent): Bayside, Beach, Centerville, Kempsville, Lynnhaven, Princess Anne, and Rose Hall.[75]

The mayor is elected to a four-year term through direct election. The mayor presides over city council meetings, and serves as the ceremonial head and spokesperson of the city. A vice mayor is also elected by the city council at the first meeting following a council election.[76]

Citizens of Virginia Beach also elect five constitutional officers, and candidates for these offices are permitted to run with an affiliated political party. Three of these offices deal substantially with public safety and justice: the sheriff, commonwealth's attorney, and the clerk of the circuit court. The two other offices are concerned with fiscal policy: the city treasurer and the commissioner of the revenue.

Virginia Beach is located entirely in the Virginia's 2nd congressional district, served by U.S. Representative Elaine Luria (Democrat).

Education

According to the U.S. Census, 28.1% of the population over twenty-five (vs. a national average of 24%) hold a bachelor's degree or higher, and 90.4% (vs. 80% nationally) have a high school diploma or equivalent.

Prior to 1969, separate schools were maintained for black and white students. Before 1938, black students who wished to attend school past seventh grade had to travel to Norfolk, and pay tuition to attend Booker T. Washington High School. In 1938, the first high school for blacks, the Princess Anne County Training School was built. In 1961, in order to avoid the stigma of the term "training school", the school was renamed Union Kempsville High School at the request of the black community. When the public schools integrated in 1969, Union Kempsville was closed.[77][78][79]

The city of Virginia Beach is home to Virginia Beach City Public Schools, one of the largest school systems in the state (based on student enrollment). Virginia Beach City Public Schools currently serves 69,735 students, and includes 56 elementary schools, 14 middle schools, 12 high schools which include Landstown, Princess Anne, Green Run, Green Run Collegiate, Cox, Tallwood, Salem, First Colonial, Kellam, Kempsville, Bayside, and Ocean Lakes High Schools as well as a number of secondary/post-secondary specialty schools and centers such as the Advanced Technology Center (ATC).

There are also a number of private, independent schools in the city, including Norfolk Academy, Our Lady of Mount Carmel Catholic School and Parish, The Hebrew Academy of Tidewater, Cape Henry Collegiate School, Catholic High School (formerly Bishop Sullivan Catholic and, before that, Norfolk Catholic), Baylake Pines School, and Virginia Beach Friends School.[80]

Virginia Beach is home to several universities. Regent University, a private university founded by Christian evangelist and leader Pat Robertson, has historically focused on graduate education but has recently established an undergraduate program as well.[81] Atlantic University is located in Virginia Beach as well. [59] Old Dominion University and Norfolk State University are in nearby Norfolk and both the University of Virginia and Virginia Tech operate satellite campuses in Virginia Beach.[82][83][84][85] Tidewater Community College, a major junior college, also has its largest campus located in the city.[86] Virginia Wesleyan University, a private liberal arts college, is located on the border with Norfolk with the physical address of the school being in Norfolk, but the majority of the campus being in Virginia Beach.[87] ECPI University's main campus is located here as well. Additional institutions of higher education are located in other communities of greater Hampton Roads.[88]

The Virginia Beach Public Library System provides free access to accurate and current information and materials to all individuals, and promotes reading as a critical life skill. The Library system has a collection of more than 1 million items including special subject collections.[89]

Media

The Virginian-Pilot, based in Norfolk, is the daily newspaper for Virginia Beach. Other papers include Veer and the New Journal and Guide. Inside Business focuses on local business news.[90]

Virginia Wesleyan College publishes its own newspaper, The Marlin Chronicle.[90]

The Norfolk-Virginia Beach area is served by a variety of radio stations on the FM and AM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area.[91]

Virginia Beach is also served by several television stations. The Norfolk-Portsmouth-Newport News designated market area (DMA) is the 42nd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[92] The major network television affiliates are WTKR 3 (CBS), WAVY-TV 10 (NBC), WVEC 13 (ABC), WTPC-TV 21 (Trinity Broadcasting Network), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ-TV 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (Fox), and WPXV 49 (ION Television). The Public Broadcasting Service station is WHRO-TV 15. Virginia Beach residents also can receive independent station WSKY broadcasting on channel 4 from Camden County, North Carolina. Some can also receive PBS affiliate WUND 2 (UNC-TV), Home Shopping Network affiliate W14DC-D from Portsmouth, Daystar Network religious television station WVAD-LD TV 25 from Chesapeake and RTV affiliate WGBS-LD broadcasting on channel 7 from Hampton. Virginia Beach is served by Cox Cable. DirecTV and Dish Network are also popular as an alternative to cable television in Virginia Beach. In addition a large portion of the city is served by Verizon FIOS.

Virginia Beach serves as the headquarters for the Christian Broadcasting Network, located adjacent to Regent University. CBN's most notable program, The 700 Club originates from the Virginia Beach studios.[93][94] In 2008, Virginia Beach became the home to the Reel Dreams Film Festival.

Infrastructure

Transportation

Virginia Beach is primarily served by the Norfolk International Airport (IATA: ORF, ICAO: KORF, FAA LID: ORF), which is now the region's major commercial airport. The airport is located near Chesapeake Bay, along the city limits straddling neighboring Norfolk.[95] Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport also provides commercial air service for the Hampton Roads area.[96] The Chesapeake Regional Airport provides general aviation services and is located five miles (8 km) outside the city limits.[97]

Virginia Beach Airport is a small, grass runway facility catering to private aircraft owners.

Rail-wise, Virginia Beach is served by Amtrak through the Norfolk and Newport News stations, via connecting buses. A high-speed rail connection at Richmond to both the Northeast Corridor and the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor are also under study.[98]

Greyhound/Trailways provides service from a central bus terminal in adjacent Norfolk. The Greyhound station in Virginia Beach is located on Laskin Road, about a mile west of the oceanfront. Bus services to New York City via the Chinatown bus, Today's Bus, is located on Newtown Road.[99]

The city is connected to I-64 via I-264, which runs from the oceanfront, intersects with I-64 on the east side of Norfolk, and continues through downtown Norfolk and Portsmouth until rejoining I-64 at the terminus of both roads in Chesapeake where Interstate 664 completes the loop which forms the Hampton Roads Beltway. Other major roads include Virginia Beach Boulevard (U.S. Route 58), Shore Drive (U.S. Route 60), which connects to Atlantic Avenue at the oceanfront, Northampton Blvd (U.S. Route 13), Princess Anne Road (State Route 165), Indian River Road (former State Route 603), Lynnhaven Parkway, Independence Boulevard, General Booth Boulevard, and Nimmo Parkway.

The city is also connected to Virginia's Eastern Shore region via the Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel (CBBT), which is the longest bridge-tunnel complex in the world and known as one of the Seven Engineering Wonders of the Modern World. The CBBT, a tolled facility carries U.S. Route 13.[100]

Transportation within the city, as well as the rest of Hampton Roads is served by a regional bus service, Hampton Roads Transit.[101] An extension of The Tide light rail system from Norfolk to the oceanfront is currently being studied.[102]

Walkability

A 2011 study by Walk Score ranked Virginia Beach 39th most walkable of fifty largest U.S. cities.[103]

Utilities

Water and sewer services are provided by the City's Department of Utilities. Virginia Beach receives its electricity from Dominion Virginia Power which has local sources including the Chesapeake Energy Center (a gas power plant), coal-fired plants in Chesapeake and Southampton County, and the Surry Nuclear Power Plant. Norfolk headquartered Virginia Natural Gas, a subsidiary of AGL Resources, distributes natural gas to the city from storage plants in James City County and Chesapeake.

Currently, water for the Tidewater area is pumped from Lake Gaston, which straddles the Virginia-North Carolina border along with the Blackwater and Nottoway rivers.

The city provides wastewater services for residents and transports wastewater to the regional Hampton Roads Sanitation District treatment plants.[104]

Healthcare

Virginia Beach is served by Sentara Virginia Beach General Hospital and Sentara Princess Anne Hospital. The former Sentara Bayside Hospital, now known as Sentara Independence, has been modified to a stand alone Emergency Department and outpatient treatment center. Sentara Leigh Hospital is just across the city line in Norfolk.[105] Beach Health clinic offers basic medical services for uninsured residents of Virginia Beach.

Notable people

- Felicia Barton, semi-finalist on American Idol

- Rudy Boesch, retired Navy SEAL and contestant on Survivor

- Jamelle Bouie, journalist, New York Times columnist, and political analyst

- Bill Bray, MLB player[106]

- Curtis Bush, kickboxer

- Gabby Douglas, Olympic gymnastics gold medalist

- Jason Dubois, MLB player[107]

- Genesis the Greykid, artist, creative, poet, writer

- Herman Goldner, mayor of St. Petersburg, Florida[108]

- Percy Harvin, NFL player

- Michael Hearst, author, musician, and composer

- Daniel Hudson, MLB player[109]

- Bubba Jenkins, NCAA Division I wrestling national champion and MMA fighter[110]

- BJ Leiderman, composer of themes for NPR shows

- Marc Leishman, professional golfer

- Evan Marriott, actor in Joe Millionaire[111]

- Bob McDonnell, former Governor of Virginia[112][113][114]

- Ryan McGinness, artist

- Shawn Morimando, MLB player[115]

- Lenda Murray, IFBB professional bodybuilder[116]

- Juice Newton, singer, songwriter

- Derrick Nnadi, NFL defensive tackle

- Pusha T, rapper

- Neil Ramírez, MLB player[117]

- J.R. Reid, NBA player

- Pat Robertson, television preacher

- Mark Ruffalo, Oscar-nominated actor; raised in Virginia Beach

- Todd Schnitt, radio personality

- Rhea Seehorn, actress known for role as Kim Wexler in Better Call Saul

- Scott Sizemore, MLB player[118]

- Chris Taylor, MLB player

- Ian Thomas, MLB player[119]

- Timbaland, music producer[120]

- Lil Tracy, rapper, singer and songwriter

- Travis Wall, choreographer and contestant on So You Think You Can Dance

- Matthew E. White, songwriter and producer

- Matt Williams, MLB player[121]

- Pharrell Williams, rapper, singer, record producer, composer and fashion designer

- Victoria Fuller (television personality), contestant on The Bachelor (season 24)

- Ryan Zimmerman, MLB player[122]

Sister cities

Virginia Beach's Sister Cities are:[123]

Virginia Beach has two Friendship City:[123]

In popular culture

The Monopoly Here and Now: The US edition (2015) of the game, released in honor of the game's 80th birthday, included Virginia Beach as a property that could be bought, sold and traded. The city was included after Hasbro held an online vote in order to determine which cities would make it into an updated version of the game. Virginia Beach received the fourth highest number of votes in the online contest, earning it a green spot on the board. The top Boardwalk spot went to Pierre, South Dakota.[124]

In the television series, The Man in the High Castle (2015–2019), which is set in an alternate 1960s, Virginia Beach is mentioned as being the site of a D-Day style invasion by Nazi Germany, which led to the defeat of the United States and its occupation.

See also

Notes

- Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1981 to 2010.

- Official records for Norfolk kept January 1874 to December 1945 at the Weather Bureau Office in downtown, and at Norfolk Int'l since January 1946. For more information, see Threadex.

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 7, 2014. Retrieved January 6, 2014.

- List of United States cities by population

- Melissa Jones (March 15, 2005). Superlatives USA: The Largest, Smallest, Longest, Shortest, and Wackiest Sites in America. Capital Books. pp. 137–. ISBN 978-1-931868-85-3. Retrieved October 12, 2012.

- "Virginia Beach History Timeline". Princess Anne County/Virginia Beach Historical Society. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- "Cape Henry Memorial". U.S. National Park System. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- Moon, Shep. "400 Years of Change". Virginia Department of Environmental Quality. Archived from the original on July 3, 2009. Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- "The Origins of Norfolk's Name". Norfolk Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 18, 2001. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- "Norfolk Becomes a Borough". Norfolk Historical Society. Archived from the original on April 21, 2001. Retrieved October 9, 2007.

- Jonathan Mark Souther, "Twixt Ocean and Pines: The Seaside Resort at Virginia Beach, 1880-1930." M.A. thesis, University of Richmond, 1996.

- Foss, William O., The Norwegian Lady and the Wreck of the Dictator. Virginia Beach, Virginia: Noreg Books, 2002. ISBN 0-9721989-0-3

- "Virginia Beach History". VirginiaBeach.com. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- "Va. Beach getting serious again about Dome site development". HamptonRoads. Hampton Roads.com, Bill Reed, November 14, 2007. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008.

- "Dome's memory will linger as a monument several activities are planned to honor the beach's now-razed former civic center". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved February 23, 2008 – via scholar.lib.vt.edu.

- "Town Center". City of Virginia Beach. Archived from the original on November 20, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- Barbara L. Brewer. "Phase I of Virginia Beach Convention Center Set to Open in June". Meetingsnet. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved March 21, 2008.

- "VIRGINIA BEACH'S GREEN LINE: SHOULD THE LINE HOLD?". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved March 21, 2008 – via scholar.lib.vt.edu.

- Fernandes, Deirdre (January 9, 2008). "Beach council tightens rules on building around Oceana". The Virginian-Pilot. Virginia Beach – via PilotOnline.com.

- Flavelle, Christopher; Schwartz, John (November 19, 2019). "As Climate Risk Grows, Cities Test a Tough Strategy: Saying 'No' to Developers". New York Times. Retrieved December 12, 2019.

- "At least 12 dead after disgruntled employee opens fire at Virginia Beach municipal center". CNN. May 31, 2019. Retrieved May 31, 2019.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- Virginia Beach Neighborhood History . Retrieved on March 20, 2008.

- "Virginia Beach City County, VA Weather - USA.com™". www.usa.com.

- "Trewartha maps". kkh.ltrr.arizona.edu. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "Chapter 47. Global mapping". www.fao.org. Retrieved January 30, 2019.

- "Climate Summary".

- "NowData - NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- Information from NOAA.

- "Station Name: VA NORFOLK INTL AP". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- "WMO Climate Normals for NORFOLK/INTL, VA 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- "Norfolk, Virginia, USA - Monthly weather forecast and Climate data". Weather Atlas. Retrieved July 3, 2019.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. U.S. Department of Commerce.

- "Virginia – Race and Hispanic Origin for Selected Cities and Other Places: Earliest Census to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on August 12, 2012. Retrieved May 4, 2012.

- From 15% sample

- "Median Family Income (In 2003 Inflation-adjusted Dollars)". Census.gov. Archived from the original on October 13, 2004. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- Bureau, U.S. Census. "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- "U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Virginia Beach city, Virginia (County)". Census Bureau QuickFacts. Retrieved September 25, 2018.

- "Virginia Beach, Virginia (VA) profile". City-data.com. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "CQ Press: City Crime Rankings 2008". Os.cqpress.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Virginia Beach city, Virginia". City-data.com. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Economic Profile". Virginia Beach Economic Development Community. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- "Agribusiness". Virginia Beach Economic Development Community. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- "Farmers Market". City of Virginia Beach. Archived from the original on September 16, 2007. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- "Economic Profile — Military". Virginia Beach Economic Development Community. Archived from the original on December 5, 2008. Retrieved March 8, 2007.

- Worldwide Space – A Travel Handbook and RV, Camping Guide: CONUS and Abroad (14 ed.). Spaceatravel.com. 2004. ISBN 1-881341-14-3. ISBN 978-1-881341-14-7

- "Welcome to Joint Expeditionary Base Little Creek-Fort Story". CNIC. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Virginia Beach city" (PDF). Virginia Employment Commission. May 12, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 17, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- "Virginia Aquarium & Marine Science Center". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- "Military Aviation Museum – Historic WWI & WWII Hangars, Aircraft, Airshows, and Adventure!". militaryaviationmuseum.org. Retrieved February 26, 2018.

- "Sandler Center for the Performing Arts". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- "National Register of Historic Places – Virginia Beach". Retrieved March 18, 2008.

- "Atlantic University". Archived from the original on February 7, 2011. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "The Neptune Festival". The Neptune Festival. June 25, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Verizon Wireless American Music Festival". Archived from the original on July 2, 2008.

- Minium, Harry (March 11, 2007). "Big-league sports not on the horizon for Norfolk". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved June 22, 2019 – via PilotOnline.com.

- "Virginia Beach Golf Courses". Thegolfcourses.net. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- "Rock and Roll Half Marathon". Elite Racing. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "Shamrock Marathon". shamrockmarathon.com. Retrieved October 8, 2019.

- "Virginia Beach Parks". Virginia Beach Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- "Mt. Trashmore Park". Virginia Beach Department of Parks and Recreation. Archived from the original on January 1, 2007. Retrieved October 5, 2007.

- "Red Wing Park". City of Virginia Beach. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- "Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge". U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, Back Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Archived from the original on December 16, 2005. Retrieved March 20, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "First Landing State Park". First Landing State Park. Retrieved March 20, 2008. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "False Cape State Park". False Cape State Park. Retrieved March 20, 2008.

- Hieatt, Kathy (November 15, 2014). "Environmental center opens at Pleasure House Point". The Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved June 22, 2019 – via PilotOnline.com.

- "Virginia Beach's Park System Ranks Eighth in the Nation". City of Virginia Beach. June 6, 2013. Retrieved July 18, 2013.

- "United States presidential election results". David Leip. 2016.

- "Virginia Beach City Manager: Form of Government". Virginia Beach City Manager. September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "Virginia Beach City Council: About Us". Virginia Beach City Council. September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on January 2, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Harki, Gary A (September 22, 2018). "Eighty years later, students from Virginia Beach's first black high school remember". The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on September 22, 2018. Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- Lucas, Joanne Harris (April 27, 2013). "The History of Princess Anne County Training School and Union Kempsville High School Princess Anne County/Virginia Beach, Virginia 1925-1969". Retrieved December 20, 2018. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "princess anne county training school union kempsville high school alumni and friends association, inc". Retrieved December 20, 2018.

- "State Recognized Accredited Schools". VIRGINIA COUNCIL FOR PRIVATE EDUCATION. Virginia Council for Private Education. September 30, 2007. Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "About Regent University". Regent University. Retrieved December 11, 2007.

- "About Norfolk State". Archived from the original on December 30, 2007. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "About Old Dominion". Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "VT Hampton Roads Center". Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "UVa. Hampton Roads Center". Archived from the original on January 2, 2008. Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "Tidewater Community College". Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "About Virginia Wesleyan". Archived from the original on April 4, 2008. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "About ECPI". Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- "Virginia Beach Public Library". Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- "Hampton Roads News Links". abyznewslinks.com. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- "Hampton Roads Radio Links". ontheradio.net. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- Holmes, Gary (September 23, 2006). "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006–2007 Season". Nielsen Media Research. Archived from the original on July 5, 2009. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- "About The 700 Club". Christian Broadcasting Network. July 30, 2014. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- "Titles with locations including Virginia Beach, Virginia, USA." IMDb. Retrieved on March 7, 2008.

- "Norfolk International Airport Mission and History". Norfolk International Airport. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- "Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport". Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport. Archived from the original on December 4, 2000. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- "Chesapeake Regional Airport". Retrieved January 12, 2008.

- "Southeast High Speed Rail". Southeast High Speed Rail. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved October 15, 2007.

- "Today's Bus". Today's Bus. Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved October 10, 2007.

- "Chesapeake Bay Bridge-Tunnel Facts". Chesapeake Bay Bridge and Tunnel Commission. Archived from the original on April 28, 2015. Retrieved November 23, 2006.

- "Hampton Roads Transit". Hrtransit.org. Archived from the original on January 23, 2000. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "Virginia Beach Transit Extension Study | Hampton Roads Transit". Gohrt.com. Archived from the original on July 3, 2010. Retrieved July 2, 2010.

- "2011 City and Neighborhood Rankings". Walk Score. 2011. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- "Hampton Roads Sanitation District". Hampton Roads Sanitation District. Archived from the original on December 12, 1998. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- "Virginia Hospitals and Medical Centers". The Agape Center. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=41288. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=5178. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Andrew Meacham, "Mayor packed ideas, pipe tobacco in rich public life," September 15, 2010". Tampa Bay Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved June 1, 2014.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=124152. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- https://thesundevils.com/news/2013/4/17/208248340.aspx. Arizona State University Official Athletic Site. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- Holtzclaw, Mike (September 5, 2015). "Evan Marriott's life interrupted by unexpected TV stardom on 'Joe Millionaire'". Daily Press. Retrieved June 8, 2017.

- "Governor Robert F. McDonnell's bio". Governor.virginia.gov. Archived from the original on March 4, 2010. Retrieved March 4, 2010.

- "Session 2005; McDonnell, Robert F. (Bob)". Virginia House of Delegates. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- "Session 2003; McDonnell, Robert F. (Bob)". Virginia House of Delegates. Retrieved November 26, 2008.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=165391. The Baseball Cube. retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Lenda Murray - Facebook".

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=128933. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Scott Sizemore Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=144094. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Timbaland's visit includes grant for Beach school". The Virginian-Pilot. May 30, 2008. Archived from the original on June 1, 2008. Retrieved January 11, 2013.

- http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=19720. The Baseball Cube. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

- "Ryan Zimmerman Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved December 10, 2012.

- "About". Sister City Association of Virginia Beach. 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2018.

- "Monopoly – Here & Now". BuzzFeed, Inc. 2015. Archived from the original on December 30, 2015.