Waterville, Maine

Waterville is a city in Kennebec County, Maine, United States, on the west bank of the Kennebec River. The city is home to Colby College and Thomas College. As of the 2010 census the population was 15,722,[4] and in 2019 the estimated population was 16,558.[5] Along with Augusta, Waterville is one of the principal cities of the Augusta-Waterville, ME Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Waterville, Maine | |

|---|---|

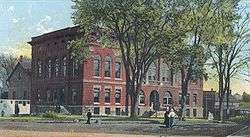

City Hall and Opera House in 1905 | |

Seal | |

| Nickname(s): Elm City | |

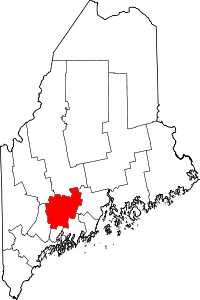

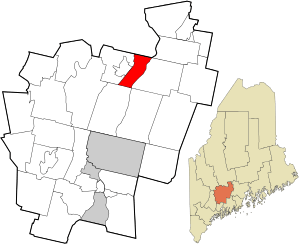

Location in Kennebec County and the state of Maine. | |

Waterville, Maine Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 44°33′7″N 69°38′45″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Maine |

| County | Kennebec |

| Incorporated (town) | June 23, 1802 |

| Incorporated | January 12, 1888 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor and council-manager |

| • Body | Waterville City Council |

| • Mayor | Nick Isgro |

| • City Manager | Mike Roy |

| Area | |

| • Total | 14.01 sq mi (36.28 km2) |

| • Land | 13.53 sq mi (35.05 km2) |

| • Water | 0.47 sq mi (1.23 km2) |

| Elevation | 108 ft (33 m) |

| Population | 15,722 |

| • Estimate (2019)[3] | 16,558 |

| • Density | 1,223.62/sq mi (472.43/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Code | 04901 |

| Area code(s) | 207 |

| FIPS code | 23-80740 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0577893 |

| Website | www |

History

The area now known as Waterville was once inhabited by the Canibas tribe of the Abenaki people. Called "Taconnet" after Chief Taconnet, the main village was located on the east bank of the Kennebec River at its confluence with the Sebasticook River at what is now Winslow. Known as "Ticonic" by English settlers, it was burned in 1692 during King William's War, after which the Canibas tribe abandoned the area. Fort Halifax was built by General John Winslow in 1754, and the last skirmish with indigenous peoples occurred on May 18, 1757.[6]

The township would be organized as Kingfield Plantation, then incorporated as Winslow in 1771. When residents on the west side of the Kennebec found themselves unable to cross the river to attend town meetings, Waterville was founded from the western parts of Winslow and incorporated on June 23, 1802. In 1824 a bridge was built joining the communities. Early industries included fishing, lumbering, agriculture and ship building, with larger boats launched in spring during freshets. By the early 1900s, there were five shipyards in the community.[7]

Ticonic Falls blocked navigation farther upriver, so Waterville developed as the terminus for trade and shipping. The Kennebec River and Messalonskee Stream provided water power for mills, including several sawmills, a gristmill, a sash and blind factory, a furniture factory, and a shovel handle factory. There was also a carriage and sleigh factory, boot shop, brickyard, and tannery. On September 27, 1849, the Androscoggin and Kennebec Railroad opened to Waterville. It would become part of the Maine Central Railroad, which in 1870 established locomotive and car repair shops in the thriving mill town. West Waterville (renamed Oakland) was set off as a town in 1873. Waterville was incorporated as a city on January 12, 1888.[8]

The Ticonic Water Power & Manufacturing Company was formed in 1866 and soon built a dam across the Kennebec. After a change of ownership in 1873, the company began construction on what would become the Lockwood Manufacturing Company, a cotton textile plant. A second mill was added, and by 1900 the firm dominated the riverfront and employed 1,300 workers. Lockwood Mills survived until the mid-1950s. The iron Waterville-Winslow Footbridge opened in 1901, as a means for Waterville residents to commute to Winslow for work in the Hollingsworth & Whitney Co. and Wyandotte Worsted Co. mills, but in less than a year was carried away by the highest river level since 1832. Rebuilt in 1903, it would be called the Two Cent Bridge because of its toll.[9] In 1902, the Beaux-Arts style City Hall and Opera House designed by George Gilman Adams was dedicated. In 2002, the C.F. Hathaway Company, one of the last remaining factories in the United States producing high-end dress shirts, was purchased by Warren Buffett's Berkshire Hathaway company and was closed after over 160 years of operation in the city.[9]

Waterville also developed as an educational center. In 1813, the Maine Literary and Theological Institution was established. It would be renamed Waterville College in 1821, then Colby College in 1867. Thomas College was established in 1894. The Latin School was founded in 1820 to prepare students to attend Colby and other colleges, and was subsequently named Waterville Academy, Waterville Classical Institute, and Coburn Classical Institute; the Institute merged with the Oak Grove School in Vassalboro in 1970, and remained open until 1989. The first public high school was built in 1877, while the current Waterville Senior High School was built in 1961.[6]

Geography

Waterville is located in northern Kennebec County at 44°33′07″N 69°38′45″W.[10] Its northern boundary is the Somerset County line.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 14.05 square miles (36.39 km2), of which 13.58 square miles (35.17 km2) are land and 0.47 square miles (1.22 km2), or 3.36%, are water.[11] Situated beside the Kennebec River, Waterville is drained by the Messalonskee Stream.

Waterville is served by Interstate 95, U.S. Route 201, and Maine State Routes 137 and 104. It is bordered by Fairfield on the north in Somerset County, Winslow on the east, Sidney on the south and Oakland on the west.

Climate

This climatic region is typified by large seasonal temperature differences, with warm to hot (and often humid) summers and cold (sometimes severely cold) winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Waterville has a humid continental climate, abbreviated "Dfb" on climate maps.[12]

| Climate data for Waterville, Maine | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 58 (14) |

61 (16) |

84 (29) |

91 (33) |

98 (37) |

96 (36) |

96 (36) |

101 (38) |

96 (36) |

84 (29) |

73 (23) |

67 (19) |

101 (38) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 29.8 (−1.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

42.5 (5.8) |

55.2 (12.9) |

67.9 (19.9) |

76.4 (24.7) |

81.3 (27.4) |

80.1 (26.7) |

71.8 (22.1) |

59.8 (15.4) |

46.7 (8.2) |

34.3 (1.3) |

56.6 (13.7) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 7.8 (−13.4) |

9.7 (−12.4) |

20.8 (−6.2) |

31.7 (−0.2) |

42.3 (5.7) |

52.1 (11.2) |

57.6 (14.2) |

56.1 (13.4) |

47.9 (8.8) |

37.5 (3.1) |

28.7 (−1.8) |

15.2 (−9.3) |

33.9 (1.1) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −32 (−36) |

−31 (−35) |

−17 (−27) |

8 (−13) |

21 (−6) |

34 (1) |

39 (4) |

35 (2) |

23 (−5) |

17 (−8) |

−1 (−18) |

−27 (−33) |

−32 (−36) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 2.87 (73) |

2.54 (65) |

3.23 (82) |

3.49 (89) |

3.51 (89) |

3.65 (93) |

3.45 (88) |

3.53 (90) |

3.57 (91) |

4.21 (107) |

4.17 (106) |

3.58 (91) |

41.8 (1,064) |

| Source: [13] | |||||||||||||

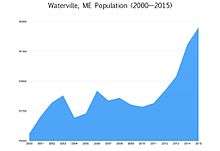

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1810 | 1,314 | — | |

| 1820 | 1,719 | 30.8% | |

| 1830 | 2,216 | 28.9% | |

| 1840 | 2,971 | 34.1% | |

| 1850 | 3,964 | 33.4% | |

| 1860 | 4,390 | 10.7% | |

| 1870 | 4,852 | 10.5% | |

| 1880 | 4,672 | −3.7% | |

| 1890 | 7,107 | 52.1% | |

| 1900 | 9,477 | 33.3% | |

| 1910 | 11,458 | 20.9% | |

| 1920 | 13,351 | 16.5% | |

| 1930 | 15,454 | 15.8% | |

| 1940 | 16,688 | 8.0% | |

| 1950 | 18,287 | 9.6% | |

| 1960 | 18,695 | 2.2% | |

| 1970 | 18,192 | −2.7% | |

| 1980 | 17,779 | −2.3% | |

| 1990 | 17,173 | −3.4% | |

| 2000 | 15,605 | −9.1% | |

| 2010 | 15,722 | 0.7% | |

| Est. 2019 | 16,558 | [3] | 5.3% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[14] | |||

2010 census

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 15,722 people, 6,370 households, and 3,274 families living in the city. The population density was 1,157.7 inhabitants per square mile (447.0/km2). There were 7,065 housing units at an average density of 520.3 per square mile (200.9/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 93.9% White, 1.1% African American, 0.6% Native American, 1.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 0.8% from other races, and 2.4% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 2.4% of the population.

There were 6,370 households, of which 24.8% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 32.9% were married couples living together, 13.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.8% had a male householder with no wife present, and 48.6% were non-families. Of all households 38.9% were made up of individuals, and 15.5% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.80.

The median age in the city was 36.8 years. 17.9% of residents were under the age of 18; 18.9% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 21.7% were from 25 to 44; 24.7% were from 45 to 64; and 16.7% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 46.8% male and 53.2% female.

2000 census

As of the census[15] of 2000, there were 15,605 people, 6,218 households, and 3,370 families living in the city. The population density was 1,148.7 people per square mile (443.3/km2). There were 6,819 housing units at an average density of 501.9 per square mile (193.7/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 95.81% White, 0.78% African American, 0.56% Native American, 1.03% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 0.42% from other races, and 1.36% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.10% of the population. 32% reported French and French Canadian ancestry, 18% English, 11% Irish, and 6% German.

There were 6,218 households, out of which 26.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.2% were married couples living together, 12.1% had a female householder with no husband present, and 45.8% were non-families. Of all households 38.6% were made up of individuals, and 16.2% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.13 and the average family size was 2.84.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 19.7% under the age of 18, 18.5% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 19.5% from 45 to 64, and 18.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 85.0 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 81.7 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $26,816, and the median income for a family was $38,052. Males had a median income of $30,086 versus $22,037 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,430. 19.2% of the population and 15.1% of families were below the federal poverty level. Statewide, 10.9% of the population was below the poverty level.[16] In Kennebec County, 11.1% of the population was below the federal poverty level. Thus, although the county poverty rate was close to the state poverty rate, the poverty rate for Waterville was higher—typical for a regional center whose suburbs had grown in population.

Out of the total population, 29.7% of those under the age of 18 and 14.7% of those 65 and older were living below the poverty line.

Economy and Redevelopment

Like many other towns in Maine and in the United States, Waterville has seen development in the suburbs and the decline of the downtown area.[17] There have been new businesses and new facilities built by Inland Hospital on Kennedy Memorial Drive. Walmart, Home Depot, and a small strip mall of other stores have been built in the northern part of the city as part of an open-air shopping center. Because of this growth, the existing and now-neighboring Elm Plaza shopping center has recently had its exterior renovated and filled most or all of its previous vacancies.

In contrast, the downtown area has had its share of hardships due to chain store growth in the city. Stores that had a long history in the downtown area have closed in recent decades, including Levine's, Butlers, Sterns, Dunhams, Alvina and Delias, and LaVerdieres. The large vacancy in The Concourse shopping center that once housed the Ames, Zayre department store, as well as Brooks Pharmacy is struggling to find tenants; as is the now vacant Main Street location of a CVS pharmacy (it moved to a brand new building on Kennedy Memorial Drive).[18] Organizations like Waterville Main St continue their efforts to revitalize downtown.

Developer Paul Boghossian has converted the old Hathaway Mill to retail, office, and residential use.[19] MaineGeneral Health agreed at the end of June 2007 to become the first tenant.[20]

Waterville's top employers include MaineGeneral Medical Center, Colby College, HealthReach Network, Northern Light Inland Hospital, Hannaford Supermarket, LL Bean, Central Maine Railroad, Shaw's Supermarket, Wal-Mart, Affiliated Healthcare Systems, Mount St. Joseph Nursing Home, Kennebec Valley Community Action Program, Care & Comfort Healthcare Temps, Thomas College, City of Waterville, The Woodlands Residential Care, and Central Maine Newspapers.[21]

Government

Local government

Waterville has a mayor and council-manager form of government, led by a mayor and a seven-member city council. The city council is the governing board, and the city manager is the chief administrative officer of the city, responsible for the management of all city affairs.

Waterville adopted a city charter in the 1970s.[22] For some 40 years, the city had a "strong mayor" system in which the mayor enjoyed broad executive powers, including the power to veto measures passed by the city council and to line-item veto budget items passed by the council.[23] In 2005, the charter was substantially revised, changing the city government to a "weak mayor" council-manager system.[23][24] Under the present system, the city manager is the chief executive.[23] The charter revision was approved by city voters by a 4-1 margin.[23] The city is currently divided into seven geographic wards, each of which elects one member of the Waterville City Council and one member of the Waterville School Board.[22]

Since 1970, the following people have served as mayor of Waterville: Richard "Spike" Carey (1970-1978), Paul Laverdiere (Republican, 1978-1982); Ann Gilbride Hill (Democrat, 1982-1986); Thomas Nale (1986-1987); Judy C. Kany (Democrat, 1988-1989); David E. Bernier (1990-1993); Thomas J. Brazier (1994-1995); Nelson Megna (1995-1996); Ruth Joseph (Democrat, 1996-1998); Nelson Madore (Democrat, 1999-2004); Paul R. LePage (Republican, 2004-2011); Dana W. Sennett (Democrat, 2011); Karen Heck (independent, 2012-2014); Nicholas Isgro (Republican, 2015–present).[25]

In 2018, Isgro faced a recall election after he made a Twitter post mocking David Hogg, a survivor of the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida. The recall effort was backed by former Mayor Karen Heck, a Democrat who had previously endorsed Isgro. Isgro later made his Twitter feed private and said that he had deleted the post.[26][27] During the recall effort, Isgro asserted that outside interests and the City Council were plotting to oust him over disputes over the city budget and taxation.[28][29] After an acrimonious recall campaign,[30][31] Waterville voters narrowly defeated the recall attempt, with 1,563 "no" votes (51%) to 1,472 "yes" votes (49%).[32]

Political makeup

Waterville is considered a Democratic stronghold in Maine's 1st congressional district.[33][34] Barack Obama received 70% of Waterville's votes in the 2008 presidential election.[35]

Voter registration

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of June 2014[36] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 4,562 | 41.25% | |||

| Unenrolled | 4,200 | 37.98% | |||

| Republican | 1,940 | 17.54% | |||

| Green Independent | 356 | 3.21% | |||

| Total | 11,058 | 100% | |||

Transportation

- Robert LaFleur Airport

- Interstate 95

- US Route 201

- State Route 100A

- State Route 137

- State Route 32

- State Route 137 Business

- State Route 11

- State Route 104

- Pan Am Railways: Waterville Intermodal Facility[37][38]

Education

Waterville Public Schools provides the city primary and secondary education. It was a part of Kennebec Valley Consolidated Schools (AOS92) from 2009 to 2018.[39]

Kennebec Valley Community College in Fairfield is the local public community college. Colby College and Thomas College are private 4-year colleges located in the city. Colby is the second highest ranked liberal arts college in Maine, according to U.S. News.[40]

In popular culture

Waterville is the set location of Camp Firewood in the Netflix show Wet Hot American Summer: First Day of Camp.

Media

Waterville is home to one daily newspaper, the Morning Sentinel and a weekly college newspaper, The Colby Echo.[41] The city is also home to Fox affiliate WPFO and Daystar rebroadcaster WFYW-LP, both serving the Portland market, and to several radio stations, including Colby's WMHB, country WEBB, adult standards WTVL and MPBN on 91.3 FM.

Sister cities

Sites of interest

- Colby College

- Colby College Museum of Art[42]

- Thomas College[43]

- Atlantic Music Festival[44]

- Maine International Film Festival

- Old Waterville High School

- Old Waterville Post Office

- Perkins Arboretum

- Waterville Historical Society - Redington Museum[45]

- Waterville Public Library

- Waterville Opera House[46]

- Waterville Main Street[47]

- Waterville - Winslow Footbridge (Two Cent Bridge)

Notable people

See also

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Census Summary File 1 (G001), Waterville city, Maine". American FactFinder. U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2019.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". Retrieved May 21, 2020.

- "History in Waterville, Maine -". Watervillemaine.net. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Coolidge, Austin J.; John B. Mansfield (1859). A History and Description of New England. Boston, Massachusetts. pp. 344–345.

- Varney, George J. (1886), Gazetteer of the state of Maine. Waterville, Boston: Russell

- Stephen Plocher. ""A Short History of Waterville, Maine" (2007)" (PDF). Waterville-me.gov. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- "US Gazetteer files 2010". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on 2012-01-25. Retrieved 2012-11-23.

- "Waterville, Maine Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase.

- "Waterville Pump Stn, Maine - Climate Summary".

- "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "2005 Report Card on Poverty" (PDF). Maine.gov. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- "Maine.gov". Main.gov. Retrieved 4 July 2018.

- Marketing the Concourse

Waterville's downtown center faces growing challenges Archived 2009-05-20 at the Wayback Machine - Hathaway center plans to be unveiled tonight at council meeting Archived 2009-05-20 at the Wayback Machine

- Urban renewal spurred project Archived 2009-05-19 at the Wayback Machine

- "Industry". Mid-Maine Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved 2020-01-28.

- Rachel Ohm, Waterville city manager responds to criticism about idea of eliminating wards, Morning Sentinel (December 13, 2018).

- Kenneth T. Palmer, Maine Politics and Government (University of Nebraska Press, 2009), p. 205.

- Amy Calder, Waterville city political partisanship, ward system likely charter commission targets, Kennebec Journal (November 29, 2012).

- History of Mayors: Waterville, Maine, 1888 — Present, City of Waterville (revised June 2017).

- "Mayor faces recall vote over tweet mocking shooting survivor". Associated Press. 2018-05-04.

- Anapol, Avery (4 May 2018). "GOP Maine mayor facing recall vote over tweet mocking Parkland survivor". The Hill.

- Rachel Ohm (May 12, 2018). "Waterville mayor says council wants 13 percent tax hike". Morning Sentinel.

- Rachel Ohm & Amy Calder (June 8, 2018). "Mayor Isgro's promise to veto budget challenged by Waterville officials, councilors". Morning Sentinel.

- Rachel Ohm (May 5, 2018). "Waterville Mayor Nick Isgro questions integrity of recall petition". Morning Sentinel.

- Rachel Ohm (May 17, 2018). "Waterville mayor attempts to frame recall election as a tax issue". Central Maine Morning Sentinel.

- Rachel Ohm (June 14, 2018). "Waterville mayor asks for apology, reimbursement after surviving recall vote". Morning Sentinel.

- "National Republican, Democratic party leaders come to Maine". Central Maine.

- "New numbers, old story in 2nd District Congressional race". Central Maine.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-05-25. Retrieved 2012-10-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Registered & Enrolled Voters - Statewide" (PDF). June 10, 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2014.

- Central Maine Growth Council Archived November 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- "Appendix E – Waterville, Maine Intermodal Facility - Review of Environmental Factors - FHWA Freight Management and Operations". Federal Highway Administration. 28 October 2009. Retrieved 18 September 2011.

- Home. Kennebec Valley Consolidated Schools. Retrieved on September 5, 2018. "Waterville Central Office Office of the Superintendent 25 Messalonskee Avenue Waterville, Maine 04901-5437 [...] Winslow Central Office 20 Dean Street Winslow, Maine 04901-5437"

- "Colby College". U.S. News. Archived from the original on 2017-02-27.

- The Colby Echo

- Colby College Museum of Art

- Thomas College

- Atlantic Music Festival

- Waterville Historical Society - Redington Museum

- Waterville Opera House

- Waterville Main Street

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Waterville, Maine. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Waterville. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Waterville (Maine). |

- City of Waterville official website

- Waterville Public Library

- Waterville Main Street

- Morning Sentinel, Waterville's newspaper

- Maine Public Broadcasting Network featured Waterville in its Hometown Economies. The video of that show is available here.