Carl Orff

Carl Orff (German: [ˈɔɐ̯f]; 10 July 1895 – 29 March 1982)[1] was a German composer and music educator,[2] best known for his cantata Carmina Burana (1937).[3] The concepts of his Schulwerk were influential for children's music education.

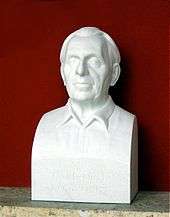

Carl Orff | |

|---|---|

Carl Orff, c. 1970 | |

| Born | 10 July 1895 Munich, Germany |

| Died | 29 March 1982 (aged 86) Munich, Germany |

Works | List of compositions |

Life

Early life

Carl Orff was born in Munich on 10 July 1895,[1] the son of Paula (Köstler) and Heinrich Orff. His family was Bavarian and was active in the Imperial German Army; his father was an army officer with strong musical interests.[4][5] His paternal grandmother was Catholic of Jewish descent.[6] At age five, Orff began to play piano, organ, and cello, and composed a few songs and music for puppet plays.[2][lower-alpha 1]

In 1911, at age 16, some of Orff's music was published.[7] Many of his youthful works were songs, often settings of German poetry. They fell into the style of Richard Strauss and other German composers of the day, but with hints of what would become Orff's distinctive musical language.

In 1911/12, Orff wrote Zarathustra, Op. 14, an unfinished large work for baritone voice, three male choruses and orchestra, based on a passage from Friedrich Nietzsche's philosophical novel Also sprach Zarathustra.[8][9] The following year, he composed an opera, Gisei, das Opfer (Gisei, the Sacrifice). Influenced by the French Impressionist composer Claude Debussy, he began to use colorful, unusual combinations of instruments in his orchestration.[10]

World War I

Moser's Musik-Lexikon states that Orff studied at the Munich Academy of Music (from 1912) until 1914.[8][11] He then served in the German Army during World War I, when he was severely injured and nearly killed when a trench caved in. Afterwards, he held various positions at opera houses in Mannheim and Darmstadt, later returning to Munich to pursue his music studies.

The 1920s

In the mid-1920s, Orff began to formulate a concept he called elementare Musik, or elemental music, which was based on the unity of the arts symbolized by the ancient Greek Muses, and involved tone, dance, poetry, image, design, and theatrical gesture. Like many other composers of the time, he was influenced by the Russian-French émigré Igor Stravinsky. But while others followed the cool, balanced neoclassic works of Stravinsky, it was works such as Les noces (The Wedding), an earthy, quasi-folkloric depiction of Russian peasant wedding rites, that appealed to Orff. He also began adapting musical works of earlier eras for contemporary theatrical presentation, including Claudio Monteverdi's opera L'Orfeo (1607). Orff's German version, Orpheus, was staged under his direction in 1925 in Mannheim, using some of the instruments that had been used in the original 1607 performance. The passionately declaimed opera of Monteverdi's era was almost unknown in the 1920s, however, and Orff's production met with reactions ranging from incomprehension to ridicule.

In 1924 Dorothee Günther and Orff founded the Günther School for gymnastics, music, and dance in Munich. Orff was there as the head of a department from 1925 until the end of his life, and he worked with musical beginners. There he developed his theories of music education, having constant contact with children. In 1930, Orff published a manual titled Schulwerk, in which he shares his method of conducting. Before writing Carmina Burana, he also edited 17th-century operas. However, these various activities brought him very little money.

Nazi era

Orff's relationship with German national-socialism and the Nazi Party has been a matter of considerable debate and analysis. His Carmina Burana was hugely popular in Nazi Germany after its premiere in Frankfurt in 1937. Given Orff's previous lack of commercial success, the monetary factor of Carmina Burana's acclaim was significant to him. But the composition, with its unfamiliar rhythms, was also denounced with racist taunts.[12] He was one of the few German composers under the Nazi regime who responded to the official call to write new incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream after the music of Felix Mendelssohn had been banned.[13] Defenders of Orff note that he had already composed music for this play as early as 1917 and 1927, long before this was a favor for the Nazi regime.

Orff was a friend of Kurt Huber, one of the founders of the resistance movement Weiße Rose (the White Rose), who was condemned to death by the Volksgerichtshof and executed by the Nazis in 1943. Orff by happenstance called at Huber's house on the day after his arrest. Huber's distraught wife, Clara, begged Orff to use his influence to help her husband, but he declined her request. If his friendship with Huber was ever discovered, he told her, he would be "ruined". On 19 January 1946 Orff wrote a letter to the deceased Huber. Later that month, he met with Clara Huber, who asked him to contribute to a memorial volume for her husband. Orff's letter was published in that collection the following year.[14] In it, Orff implored him for forgiveness.[15]

He had a long friendship with German-Jewish musicologist, composer and refugee Erich Katz,[16] who fled Nazi Germany in 1939.

Denazification

According to Canadian historian Michael H. Kater, during Orff's denazification process in Bad Homburg, Orff claimed that he had helped establish the White Rose resistance movement in Germany. There was no evidence for this other than his own word, and other sources dispute his claim. Kater also made a particularly strong case that Orff collaborated with Nazi German authorities.[17]

However, in Orff's denazification file, discovered by Viennese historian Oliver Rathkolb in 1999, no remark on the White Rose is recorded;[18] and in Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits (2000) Kater recanted his earlier accusations to some extent.[19]

In any case, Orff's assertion that he had been anti-Nazi during the war was accepted by the American denazification authorities, who changed his previous category of "gray unacceptable" to "gray acceptable", enabling him to continue to compose for public presentation, and to enjoy the royalties that the popularity of Carmina Burana had earned for him.[20]

After World War II

Most of Orff's later works – Antigonae (1949), Oedipus der Tyrann (Oedipus the Tyrant, 1958), Prometheus (1968), and De temporum fine comoedia (Play on the End of Times, 1971) – were based on texts or topics from antiquity. They extend the language of Carmina Burana in interesting ways, but they are expensive to stage and (on Orff's own admission) are not operas in the conventional sense. Live performances of them have been few, even in Germany.

Personal life

Orff was a Roman Catholic.[1][21] He was married four times: to Alice Solscher (m. 1920, div. 1925), Gertrud Willert (m. 1939, div. 1953), Luise Rinser (m. 1954, div. 1959) and Liselotte Schmitz (m. 1960). His only child Godela (1921–2013) was from his first marriage.[22] She has described her relationship with her father as having been difficult at times. "He had his life and that was that," she tells Tony Palmer in the documentary O Fortuna.[23]

Death

Orff died of cancer in Munich in 1982 at the age of 86.[3] He had lived through four epochs: the German Empire, the Weimar Republic, Nazi Germany and the post World War II West German Bundesrepublik. Orff was buried in the Baroque church of the beer-brewing Benedictine priory of Andechs, southwest of Munich. His tombstone bears his name, his dates of birth and death, and the Latin inscription Summus Finis (the Ultimate End), which is taken from the end of De temporum fine comoedia.

Works

Musical works

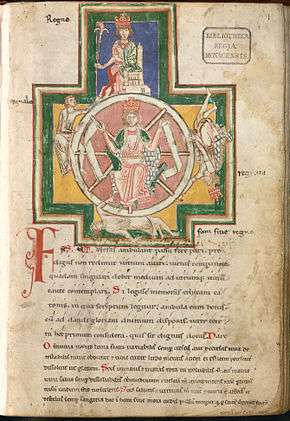

Orff is best known for Carmina Burana (1936), a "scenic cantata". It is the first part of a trilogy that also includes Catulli Carmina and Trionfo di Afrodite. Carmina Burana reflected his interest in medieval German poetry. The trilogy as a whole is called Trionfi, or "Triumphs". The composer described it as the celebration of the triumph of the human spirit through sexual and holistic balance. The work was based on thirteenth-century poetry found in a manuscript dubbed the Codex latinus monacensis found in the Benedictine monastery of Benediktbeuern in 1803 and written by the Goliards; this collection is also known as Carmina Burana. While "modern" in some of his compositional techniques, Orff was able to capture the spirit of the medieval period in this trilogy, with infectious rhythms and simple harmonies. The medieval poems, written in Latin and an early form of German, are often racy, but without descending into smut. "Fortuna Imperatrix Mundi", commonly known as "O Fortuna", from Carmina Burana, is often used to denote primal forces, for example in the Oliver Stone film The Doors.[24] The work's association with fascism also led Pier Paolo Pasolini to use the movement "Veris leta facies" to accompany the concluding scenes of torture and murder in his final film Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom.[25]

With the success of Carmina Burana, Orff disowned all of his previous works except for Catulli Carmina and the Entrata (an orchestration of "The Bells" by William Byrd (1539–1623)), which he rewrote. Later on, however, many of these earlier works were released (some even with Orff's approval). Carmina Burana was so popular that Orff received a commission in Frankfurt to compose incidental music for A Midsummer Night's Dream, which was supposed to replace the banned music by Mendelssohn. After several performances of this music, he claimed not to be satisfied with it, and reworked it into the final version that was first performed in 1964.

About his Antigonae (1949), Orff said specifically that it was not an opera but rather a Vertonung, a "musical setting", of the ancient tragedy. The text is a German translation by Friedrich Hölderlin of the Sophocles play of the same name. The orchestration relies heavily on the percussion section and is otherwise fairly simple. It has been labelled by some as minimalistic, a term which is most pertinent in terms of the melodic line.

Orff's last work, De temporum fine comoedia (Play on the End of Times), had its premiere at the Salzburg Festival on August 20, 1973, and was performed by Herbert von Karajan and the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne and Chorus. In this highly personal work, Orff presented a mystery play, sung in Greek, German, and Latin, in which he summarized his view of the end of time.

Gassenhauer, Hexeneinmaleins, and Passion, which Orff composed with Gunild Keetman, were used as theme music for Terrence Malick's film Badlands (1973).

Pedagogic works

In pedagogical circles he is probably best remembered for his Schulwerk ("School Work"). Originally a set of pieces composed and published for the Güntherschule (which had students ranging from 12 to 22),[26] this title was also used for his books based on radio broadcasts in Bavaria in 1949. These pieces are collectively called Musik für Kinder (Music for Children), and also use the term Schulwerk, and were written in collaboration with his former pupil, composer and educator Gunild Keetman, who actually wrote most of the settings and arrangements in the "Musik für Kinder" ("Music for Children") volumes.

The Music for Children volumes were not designed to be performance pieces for the average child. Many of the parts are challenging for teachers to play. They were designed as examples of pieces that show the use of ostinati, bordun, and appropriate texts for children. Teachers using the volumes are encouraged to simplify the pieces, to write original texts for the pieces and to modify the instrumentation to adapt to the teacher's classroom situation.

Orff's ideas were developed, together with Gunild Keetman, into a very innovative approach to music education for children, known as the Orff Schulwerk. The music is elemental and combines movement, singing, playing, and improvisation.

List of compositions

- Lamenti

- Orpheus (1924, reworked 1939)

- Klage der Ariadne (1925, reworked 1940)

- Tanz der Spröden (1925, reworked 1940)

- Entrata for orchestra, after "The Bells" by William Byrd (1539–1623) (1928, reworked 1941)

- Orff Schulwerk

- Musik für Kinder (with Gunild Keetman) (1930–35, reworked 1950–54)

- Tanzstück (1933)

- Gassenhauer

- Trionfi

- Carmina Burana (1937)

- Catulli Carmina (1943)

- Trionfo di Afrodite (1953)

- Märchenstücke (Fairy tales)

- Bairisches Welttheater (Bavarian world theatre)

- Die Bernauerin (1947)

- Astutuli (1953)

- Comoedia de Christi Resurrectione (1956) – Easter Play

- Ludus de Nato Infante Mirificus (1961) – Nativity play

- Theatrum Mundi

- Antigonae (1949)

- Oedipus der Tyrann (1959)

- Prometheus (1968)

- De temporum fine comoedia (1973, reworked 1977)

Notes

- Fanny von Kraft (1833–1919).[1] Her parents were baptized catholic.

References

- Dangel-Hofmann 1999.

- Randel, Don. Harvard Dictionary of Music.

- Rothstein, Edward (31 March 1982). "Carl Orff, teacher and composer Of Carmina Burana, dead at 86". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

Carl Orff, the German composer and music educator best known for his 1937 work Carmina Burana, died of cancer Monday night in a Munich, West Germany, clinic. He was 86 years old.

- "Music and History: Carl Orff". www.musicandhistory.com. Retrieved 2019-03-05.

- "Personentreffer: Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften". badw.de. Retrieved 2019-01-14.

- Kater 1995, p. 30.

- e.g. Early Songs published by Schott Music and Songs and Chants recorded by WERGO

- "Chronology". Carl Orff Center. Munich. 2018. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Fassone, Alberto (2001). "Orff, Carl". Grove Music Online (8th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Buening, Eleonore (7 July 1995). "Die Musik ist schuld". Die Zeit (in German). Hamburg. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Moser, Hans Joachim (1943). "Orff, Carl". Musiklexikon (2nd ed.). Berlin: Max Hesses Verlag. pp. 650–651.

- "Carl Orff: Carmina Burana" Ev. Emmaus-Ölberg-Kirchengemeinde Berlin Kreuzberg. Retrieved June 26, 2011 (in German)

- Rockwell, John (December 5, 2003). "Reverberations; Going Beyond 'Carmina Burana,' and Beyond Orff's Stigma". The New York Times. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Kater 1995, pp. 28–29, Orff's letter is printed in Kurt Huber zum Gedächtnis. Bildnis eines Menschen, Denkers und Forschers, dargestellt von seinen Freunden, edited by Clara Huber (Regensburg: Josef Habbel, 1947): 166–68.

- Duchen, Jessica (4 December 2008). "Dark heart of a masterpiece: Carmina Burana's famous chorus hides a murky Nazi past". The Independent. UK. Archived from the original on January 18, 2009. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- List of items in Erich Katz Collection Archive (PDF) Regis University. p. 6. Retrieved November 1, 2011

- Review of "Carl Orff im Dritten Reich" Archive, by David B. Dennis, Loyola University Chicago (January 25, 1996)

- Schleusener, Jan (11 February 1999). "Komponist sein in einer bösen Zeit". Die Welt (in German). Berlin. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- Kater 2000.

- Kater 1995.

- "Carl Orff", Classical.net

- "Godela Orff (1921–2013)", geni.com

- Kettle, Martin (2 January 2009). "Secret of the White Rose". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

- IMDb entry for soundtrack of Oliver Stone's film The Doors (scroll to bottom)

- "Pasolini's Salo", review

- Carl Orff Documentation trans. Margaret Murray, published by Schott Music, 1978

Sources

- Dangel-Hofmann, Frohmut (1999), "Orff, Carl", Neue Deutsche Biographie (NDB) (in German), 19, Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 588–591; (full text online)

- Kater, Michael H. (1995). "Carl Orff im Dritten Reich" [Carl Orff in the Third Reich] (PDF, 1.6 MB). Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte (in German). 43 (1): 1–35. ISSN 0042-5702.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kater, Michael H. (2000). Composers of the Nazi Era: Eight Portraits. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195152869.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Dangel-Hofmann, Frohmut (1990). Carl Orff – Michel Hofmann. Briefe zur Entstehung der Carmina burana. Tutzing: Hans Schneider. ISBN 3-7952-0639-1.

- Edelmann, Bernd (2011). "Carl Orff". In Weigand, Katharina (ed.). Große Gestalten der bayerischen Geschichte. Munich: Herbert Utz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8316-0949-9.

- Fassone, Alberto (2009). Carl Orff (2nd revised and enlarged ed.). Lucca: Libreria Musicale Italiana. ISBN 978-887096-580-3.

- Gersdorf, Lilo (2002). Carl Orff. Reinbek: Rowohlt. ISBN 3-499-50293-3.

- Kaufmann, Harald (1993). "Carl Orff als Schauspieler". In Grünzweig, Werner; Krieger, Gottfried (eds.). Von innen und außen. Schriften über Musik, Musikleben und Ästhetik. Hofheim: Wolke. pp. 35–40.

- Kugler, Michael, ed. (2002). Elementarer Tanz – Elementare Musik: Die Günther-Schule München 1924 bis 1944. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 3-7957-0449-9.

- Liess, Andreas (1980). Carl Orff. Idee und Werk (revised ed.). Munich: Goldmann. ISBN 3-442-33038-6.

- Massa, Pietro (2006). Carl Orffs Antikendramen und die Hölderlin-Rezeption im Deutschland der Nachkriegszeit. Bern/Frankfurt/New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-631-55143-6.

- Orff, Godela (1995). Mein Vater und ich. Munich: Piper. ISBN 3-492-18332-8.

- Carl Orff und sein Werk. Dokumentation. 8 voll. Schneider, Tutzing 1975–1983, ISBN 3-7952-0154-3, ISBN 3-7952-0162-4, ISBN 3-7952-0202-7, ISBN 3-7952-0257-4, ISBN 3-7952-0294-9, ISBN 3-7952-0308-2, ISBN 3-7952-0308-2, ISBN 3-7952-0373-2.

- Rösch, Thomas (2003). Die Musik in den griechischen Tragödien von Carl Orff. Tutzing: Hans Schneider. ISBN 3-7952-0976-5.

- Rösch, Thomas (2009). Carl Orff – Musik zu Skakespeares "Ein Sommernachtstraum". Entstehung und Deutung. Munich: Orff-Zentrum.

- Rösch, Thomas, ed. (2015). Text, Musik, Szene – Das Musiktheater von Carl Orff. Symposium Orff-Zentrum München 2007. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 978-3-7957-0672-2.

- Thomas, Werner (1990). Das Rad der Fortuna – Ausgewählte Aufsätze zu Werk und Wirkung Carl Orffs. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 978-3-7957-0209-0.

- Thomas, Werner (1994). Orffs Märchenstücke. Der Mond – Die Kluge. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 978-3-7957-0266-3.

- Thomas, Werner (1997). Dem unbekannten Gott. Ein nicht ausgeführtes Chorwerk von Carl Orff. Mainz: Schott. ISBN 978-3-7957-0323-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Carl Orff. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Carl Orff |

- Carl Orff Foundation

- Orff Center, Munich

- Discography

- Profile, works, discography, Archive Schott Music

- Carl Orff at Schott Music

- Carl Orff on IMDb

- Interview with conductor Ferdinand Leitner by Bruce Duffie. Leitner was a close friend of Orff and conducted many of his works, including several premieres.