Bosnian Church

The Bosnian Church (Bosnian: Crkva bosanska/Црква босанска) was a Christian church in medieval Bosnia that was independent of and considered heretical by both the Roman Catholic and the Eastern Orthodox hierarchies.

| Bosnian Church Crkva bosanska/Црква босанска | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governance | |

| Origin | 11th century |

| Separated from | Roman Catholic Diocese of Bosnia[1] |

| Other name(s) | Crkva bosansko-humskih krstjana |

Historians have traditionally connected the church with the Bogomils, although this has been challenged and is now rejected by most scholars. Adherents of the church called themselves simply krstjani ("Christians") or dobri Bošnjani ("Good Bosnians"). The church's organization and beliefs are poorly understood, because few if any records were left by church members and the church is mostly known from the writings of outside sources - primarily Roman Catholic ones.

The monumental tombstones called Stećak that appeared in medieval Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well Croatia, Serbia and Montenegro, are sometime identified with the Bosnian Church.

Background

Schism

Christian missions emanating from Rome and Constantinople started pushing into the Balkans in the 9th century, Christianizing the South Slavs and establishing boundaries between the ecclesiastical jurisdictions of the See of Rome and the See of Constantinople. The East–West Schism then led to the establishment of Roman Catholicism in Croatia and most of Dalmatia, while Eastern Orthodoxy came to prevail in Serbia.[2] Lying in-between, the mountainous Bosnia was nominally under Rome,[2] but Catholicism never became firmly established due to a weak church organization[2] and poor communications.[3] Medieval Bosnia thus remained a "no-man's land between faiths" rather than a meeting ground between the two Churches,[3] leading to a unique religious history and the emergence of an "independent and somewhat heretical church".[2]

Roman Catholicism and Eastern Orthodoxy predominated in different parts of what is today Bosnia and Herzegovina; the followers of the former formed a majority in the west, the north and in the center of Bosnia, while those of the latter were a majority in most of Zachlumia (present-day Herzegovina) and along Bosnia's eastern border. This changed in the mid-13th century, when the Bosnian Church began eclipsing the Roman.[4] While Bosnia remained nominally Catholic in the High Middle Ages, the Bishop of Bosnia was a local cleric chosen by Bosnians and then sent to the Archbishop of Ragusa solely for ordination. Although the Papacy already insisted on using Latin as the liturgical language, Bosnian Catholics retained Church Slavonic language.[4]

Abjuration and crusade

Vukan, ruler of Dioclea, wrote to Pope Innocent III in 1199 that Kulin, ruler of Bosnia, had become a heretic, along with his wife, sister, other relatives and 10,000 other Bosnians. The Archbishop of Spalato, vying for control over Bosnia, joined Vukan and accused the Archbishop of Ragusa of neglecting his suffragan diocese in Bosnia. Emeric, King of Hungary and supporter of Spalato, also seized this opportunity to try to extend his influence over Bosnia.[5] Further accusations against Kulin, such as harbouring heretics, ensued until 1202. In 1203, Kulin moved to defuse the threat of foreign intervention. A synod was held at his instigation on 6 April. Following the Abjuration of Bilino Polje, Kulin succeeded in keeping the Bosnian Diocese under the Ragusan Archdiocese, thus limiting Hungarian influence. The errors abjured by the Bosnians in Bilino Polje seem to have been errors of practice, stemming from ignorance, rather than heretical doctrines.[6]

History

The bid to consolidate Roman Catholic rule in Bosnia in the 12th to 13th centuries proved difficult. The Banate of Bosnia held strict trade relations with the Republic of Ragusa, and Bosnia's Bishop was under the jurisdiction of Ragusa. This was disputed by the Hungarians, who tried to achieve their jurisdiction over Bosnia's bishops, but Bosnia's first Ban Kulin averted that. In order to conduct a crusade against him, the Hungarians turned to Rome, complaining to Pope Innocent III that the Kingdom of Bosnia was a centre of heresy, based on the refuge that some Cathars (also known as Bogomils or patarenes) had found there. To avert the Hungarian attack, Ban Kulin held a public assembly on 8 April 1203 and affirmed his loyalty to Rome in the presence of an envoy of the Pope, while the faithful abjured their mistakes and committed to following the Roman Catholic doctrine.[7] Yet, in practice this was ignored. On the death of Kulin in 1216 a mission was sent to convert Bosnia to Rome but failed.[8]

On 15 May 1225 Pope Honorius III spurred the Hungarians to undertake the Bosnian Crusade. That expedition, like the previous ones, turned into a defeat, and the Hungarians had to retreat when the Mongols invaded their territories. In 1234, the Catholic Bishop of Bosnia was removed by Pope Gregory IX for allowing supposedly heretical practices.[8] In addition, Gregory called on the Hungarian king to crusade against the heretics in Bosnia.[9] However, Bosnian nobles were able to expel the Hungarians once again.[10]

In 1252, Pope Innocent IV decided to put Bosnia's Bishop under the Hungarian Kalocsa jurisdiction. This decision provoked the schism of the Bosnian Christians, who refused to submit to the Hungarians and broke off their relations with Rome.[11] In that way, an autonomous Bosnian Church came into being, in which many scholars later saw a Bogomil or Cathar church, whilst more recent scholars such as Noel Malcolm and John Fine maintain that no trace of Bogomilism, Catharism or other dualism can be found in the original documents of the Bosnian Christians.[12]

It was not until Pope Nicholas' Bull Prae Cunctis in 1291 that the Franciscan-led inquisition was imposed on Bosnia.[13] Bogomilism was eradicated in Bulgaria and Byzantium in the 13th century, but survived in Bosnia and Herzegovina until the Ottoman Empire gained control of the region in 1463.

The Bosnian Church coexisted with the Catholic Church (and with the few Bogomil groups) for most of the late Middle Ages, but no accurate figures exist as to the numbers of adherents of the two churches. Several Bosnian rulers were Krstjani, while others adhered to Catholicism for political purposes. Stjepan Kotromanić shortly reconciled Bosnia with Rome, while ensuring at the same time the survival of the Bosnian Church. Notwithstanding the incoming Franciscan missionaries, the Bosnian Church survived, although weaker and weaker, until it disappeared after the Ottoman conquest.[14]

Outsiders accused the Bosnian Church of links to the Bogomils, a stridently dualist sect of dualist-gnostic Christians heavily influenced by the Manichaean Paulician movement and also to the Patarene heresy (itself only a variant of the same belief system of Manichean-influenced dualism). The Bogomil heretics were at one point mainly centered in Bulgaria and are now known by historians as the direct progenitors of the Cathars. The Inquisition reported the existence of a dualist sect in Bosnia in the late 15th century and called them "Bosnian heretics", but this sect was according to some historians most likely not the same as the Bosnian Church. The historian Franjo Rački wrote about this in 1869 based on Latin sources, but the Croatian scholar Dragutin Kniewald in 1949 established the credibility of the Latin documents in which the Bosnian Church is described as heretical.[15] It is thought today that the Bosnian Church's adherents, who were persecuted by both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Churches, were predominantly converted to Islam upon the arrival of the Ottomans, thus adding to the ethnogenesis of the modern-day Bosniaks.[14] According to Bašić, the Bosnian Church was dualist in character, and so was neither a schismatic Catholic nor Orthodox Church.[16] According to Mauro Orbini (d. 1614), the Patarenes and the Manicheans[17] were two Christian religious sects in Bosnia. The Manicheans had a bishop called djed and priests called strojnici (strojniks), the same titles ascribed to the leaders of the Bosnian Church.[18] The church left a few traditions to those who converted to Islam, one of which is having mosques built out of wood because many Bogomilian churches were primarily built of wood.

Some historians reckon that the Bosnian Church had largely disappeared before the Turkish conquest in 1463. Other historians dispute a discrete terminal point.

The religious centre of the Bosnian Church was located in Moštre, near Visoko, where the House of Krstjani was founded.[19]

Organization and characteristics

The Bosnian Church used Slavic language in liturgy, as did the Orthodox.[20]

Djed

The church was headed by a bishop, called djed ("grandfather"), and had a council of twelve men called strojnici. The monk missionaries were known as krstjani or kršćani ("adherents of the cross").[20] Some of the adherents resided in small monasteries, known as hiže (hiža, "house"), while others were wanderers, known as gosti (gost, "guest").[20] It is difficult to ascertain how the theology differed from that of the Orthodox and Catholic.[20] The practices were, however, unacceptable to both.[20]

The Church was mainly composed of monks in scattered monastic houses. It had no territorial organization and it did not deal with any secular matters other than attending people's burials. It did not involve itself in state issues very much. Notable exceptions were when King Stephen Ostoja of Bosnia, a member of the Bosnian Church himself, had a djed as an advisor at the royal court between 1403 and 1405, and an occasional occurrence of a krstjan elder being a mediator or diplomat.

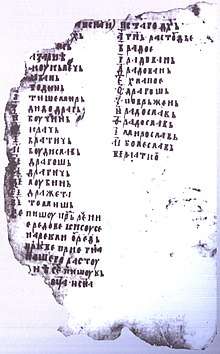

Hval's Codex

Hval's Codex, written in 1404 in Bosnian Cyrillic, is one of the most famous manuscripts belonging to the Bosnian Church in which there are some iconographic elements which are not in concordance with the supposed theological doctrine of Christians (Annunciation, Crucifixion and Ascension). All the important Bosnian Church books (Nikoljsko evandjelje, Sreckovicevo evandelje, the Manuscript of Hval, the Manuscript of Krstyanin Radosav) are based on Glagolitic Church books.

Studies

The phenomenon of Bosnian medieval Christians attracted scholars' attention for centuries, but it was not until the latter half of the 19th century that the most important monograph on the subject, "Bogomili i Patareni" (Bogomils and Patarens), 1870, by eminent Croatian historian Franjo Rački, was published. Rački argued that the Bosnian Church was essentially Gnostic and Manichaean in nature. This interpretation has been accepted, expanded and elaborated upon by a host of later historians, most prominent among them being Dominik Mandić, Sima Ćirković, Vladimir Ćorović, Miroslav Brandt and Franjo Šanjek. However, a number of other historians (Leon Petrović, Jaroslav Šidak, Dragoljub Dragojlović, Dubravko Lovrenović, and Noel Malcolm) stressed the impeccably orthodox theological character of Bosnian Christian writings and claimed the phenomenon can be sufficiently explained by the relative isolation of Bosnian Christianity, which retained many archaic traits predating the East-West Schism in 1054.

Conversely, the American historian of the Balkans, Prof. John Fine, does not believe in the dualism of the Bosnian Church at all.[21] Though he represents his theory as a "new interpretation of the Bosnian Church", his view is very close to J. Šidak's early theory and that of several other scholars before him.[22] He believes that while there could have been heretical groups alongside of the Bosnian Church, the church itself was inspired by Papal overreach.

References

- Lovrenović, Dubravko (2006). "Strast za istinom moćnija od strasti za mitologiziranjem" (pdf available for read/download). STATUS Magazin za političku kulturu i društvena pitanja (in Croatian) (8): 182–189. ISSN 1512-8679. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- Fine 1991, p. 8.

- Fine 1994, p. 17.

- Fine 1994, p. 18.

- Fine 1994, p. 45.

- Fine 1994, p. 47.

- Thierry Mudry, Histoire de la Bosnie-Herzégovine faits et controverses, Éditions Ellipses, 1999 (chapitre 2: La Bosnie médiévale p. 25 à 42 et chapitre 7 : La querelle historiographique p. 255 à 265). Dennis P. Hupchick et Harold E. Cox, Les Balkans Atlas Historique, Éditions Economica, Paris, 2008, p. 34

- Malcolm Lambert, Medieval Heresy:Popular Movements from Bogomil to Hus, (Edward Arnold Ltd, 1977), 143.

- Christian Dualist Heresies in the Byzantine World, C. 650-c. 1450, ed. Janet Hamilton, Bernard Hamilton, Yuri Stoyanov, (Manchester University Press, 1998), 48-49.

- Malcolm Lambert, Medieval Heresy:Popular Movements from Bogomil to Hus, 143.

- Mudry 1999; Hupchick and Cox 2008

- The issue of the Bogomil hypothesis is dealt with by Noel Malcolm (Bosnia. A Short History) as well as by John V.A. Fine (in Mark Pinson, The Bosnian Muslims)

- Mitja Velikonja, Religious Separation and Political Intolerance in Bosnia-Herzegovina, transl. Rang'ichi Ng'inga, (Texas A&M University Press, 2003), 35.

- Davide Denti, L’EVOLUZIONE DELL’ISLAM BOSNIACO NEGLI ANNI ‘90, tesi di laurea in Scienze Internazionali, Università degli Studi di Milano, 2006

- Denis Bašić. The roots of the religious, ethnic, and national identity of the Bosnian-Herzegovinan [sic] Muslims. University of Washington, 2009, 369 pages (p. 194).

- Denis Bašić, p. 186.

- The Paulicians and Bogomils have been confounded with the Manichaeans. L. P. Brockett, The Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia - The Early Protestants of the East. Appendix II, http://www.reformedreader.org/history/brockett/bogomils.htm

- Mauro Orbini. II Regno Degli Slav: Presaro 1601, p.354 and Мавро Орбини, Кралство Словена, p. 146.

- Old town Visoki declared as national monument Archived February 20, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. 2004.

- Stoianovich 2015, p. 145.

- Fine, John. The Bosnian Church: Its Place in State and Society from the Thirteenth to the Fifteenth Century: A New Interpretation. London: SAQI, The Bosnian Institute, 2007. ISBN 0-86356-503-4

- Denis Bašić, p. 196.

Sources

- Stoianovich, Traian (2015). Balkan Worlds: The First and Last Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-47615-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp, Jr. (1991). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472081497.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1975). "The Bosnian Church: a new interpretation: a study of the Bosnian Church and its place in state and society from the 13th to the 15th centuries". East European Quarterly. 10.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp, Jr. (1994). The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08260-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lambert, Malcolm D. (1977). Medieval heresy: popular movements from Bogomil to Hus. Holmes & Meier Publishers.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bosnian Church. |

- Crkva Bosanska - Kršćanska zajednica u BiH

- L. P. Brockett, The Bogomils of Bulgaria and Bosnia - The Early Protestants of the East