Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (often abbreviated KP or KPK) (Pashto: خیبر پښتونخوا ; Urdu: خیبر پختونخوا),[1] formerly known as the North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) (Urdu: صوبہ سرحد), is one of the four provinces of Pakistan, located in the northwestern region of the country along the International border with Afghanistan.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa خیبر پختونخوا خیبر پښتونخوا | |

|---|---|

Top left to right: Bab-e-Khyber, Mohabbat Khan Mosque, Kalam Valley, Bahrain, Swat Valley and Lake Saiful Muluk | |

Flag  Seal | |

.svg.png) Location of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in Pakistan | |

| Coordinates: 34.00°N 71.32°E | |

| Country | |

| Established | 1 July 1970 |

| Capital | Peshawar |

| Largest city | Peshawar |

| Government | |

| • Type | Self-governing Province subject to the Federal Government |

| • Body | Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |

| • Governor | Shah Farman (PTI)[1] |

| • Chief Minister | Mahmood Khan (PTI) |

| • Chief Secretary | Dr. Kazim Niaz[2] |

| • Legislature | Provincial Assembly |

| • High Court | Peshawar High Court |

| Area | |

| • Total | 101,741 km2 (39,282 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 4th |

| Population (2017)[3] | |

| • Total | 35,525,047[lower-alpha 1] |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| Time zone | UTC+05:00 (PST) |

| Area code(s) | 9291 |

| ISO 3166 code | PK-KP |

| Main Language(s) | |

| Notable sports teams | Peshawar Zalmi Peshawar Panthers |

| Seats in National Assembly | 65 |

| HDI (2018) | 0.529 Low |

| Seats in Provincial Assembly | 145 |

| Divisions | 7 |

| Districts | 35 |

| Tehsils | 105 |

| Union Councils | 986 |

| Website | www |

It was previously known as the North-West Frontier Province until 2010 when the name was changed to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa by the 18th Amendment to Pakistan's Constitution and is known colloquially by various other names. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is the third-largest province of Pakistan by the size of both population and economy, though it is geographically the smallest of four.[5] Within Pakistan, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shares a border with Punjab, Balochistan, Azad Kashmir, Gilgit-Baltistan and Islamabad. It is home to 17.9% of Pakistan's total population, with the majority of the province's inhabitants being Pashtuns and Hindko speakers.

The province is the site of the ancient kingdom Gandhara, including the ruins of its capital Pushkalavati near modern-day Charsadda. Once a stronghold of Buddhism, the history of the region was characterized by frequent invasions by various empires due to its geographical proximity to the Khyber Pass.[6]

On 2 March 2017, the Government of Pakistan considered a proposal to merge the Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA) with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and to repeal the Frontier Crimes Regulations, which were applicable to the tribal areas at the time.[7] However, some political parties opposed the merger, and called for the tribal areas to instead become a separate province of Pakistan.[8] On 24 May 2018, the National Assembly of Pakistan voted in favour of an amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan to merge the Federally Administered Tribal Areas with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.[9] The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Assembly then approved the historic FATA-KP merger bill on 28 May 2018 making FATA officially part of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,[10] which was then signed by President Mamnoon Hussain, completing the process of this historic merger.[11][12]

Etymology

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa means the "Khyber side of the land of the Pashtuns,[13] where the word Pakhtunkhwa means "Land of the Pashtuns",[14] while according to some scholars, it refers to "Pashtun culture and society".[15]

When the British established it as a province, they called it "North West Frontier Province" (abbreviated as NWFP) due to its relative location being in north west of their Indian Empire.[16] After the creation of Pakistan, Pakistan continued with this name but a Pashtun nationalist party, Awami National Party demanded that the province name be changed to "Pakhtunkhwa".[17] Their logic behind that demand was that Punjabi people, Sindhi people and Balochi people have their provinces named after their ethnicities but that is not the case for Pashtun people.[18]

Pakistan Muslim League (N) was against that name since it was too similar to Bacha Khan's demand of a separate nation of Pashtunistan.[19] PML-N wanted to name the province something other than which does not carry Pashtun identity in it as they argued that there were other minor ethnicities living in the province especially Hindkowans who spoke Hindko, thus the word Khyber was introduced with the name because it is the name of a major pass which connects Pakistan to Afghanistan.[18]

| Provincial flag | Flag of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |  |

|---|---|---|

| Provincial Insignia | Emblem of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa |  |

| Provincial animal | Straight-horned Markhor |  |

| Provincial bird | White-crested Kalij pheasant | .jpg) |

| Provincial tree | Pine tree | |

| Provincial flower | Lady's tulip |  |

| Provincial sport | Archery | .jpg) |

History

Early history

During the times of Indus Valley Civilization (3300 BCE – 1300 BCE) the modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's Khyber Pass, through Hindu Kush provided a route to other neighboring regions and was used by merchants on trade excursions.[20] From 1500 BCE, Indo-Aryan peoples started to enter in the region(of modern-day Iran, Pakistan, Afghanistan, North India) after having passed Khyber Pass.[21][22]

The Gandharan civilization, which reached its zenith between the sixth and first centuries BCE, and which features prominently in the Hindu epic poem, the Mahabharatha,[23] had one of its cores over the modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province. Vedic texts refer to the area as the province of Pushkalavati. The area was once known to be a great center of learning.[24]

Persian and Greek Invasions

At around 516 BCE., Darius Hystaspes sent Scylax, a Greek seaman from Karyanda, to explore the course of the Indus river. Darius Hystaspes subsequently subdued the races dwelling west of the Indus and north of Kabul. Gandhara was incorporated into the Persian Empire as one of its far easternmost satrapy system of government. The satrapy of Gandhara is recorded to have sent troops for Xerxes' invasion of Greece in 480 BCE.[23]

In the spring of 327 BCE, Alexander the Great crossed the Indian Caucasus (Hindu Kush) and advanced to Nicaea, where Omphis, king of Taxila and other chiefs joined him. Alexander then dispatched part of his force through the valley of the Kabul River, while he himself advanced into modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's Bajaur and Swat regions with his troops.[23] Having defeated the Aspasians, from whom he took 40,000 prisoners and 230,000 oxen, Alexander crossed the Gouraios (Panjkora River) and entered into the territory of the Assakenoi – also in modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Alexander then made Embolima (thought to be the region of Amb in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa) his base. The ancient region of Peukelaotis (modern Hashtnagar, 17 miles (27 km) north-west of Peshawar) submitted to the Greek invasion, leading to Nicanor, a Macedonian, being appointed satrap of the country west of the Indus, which includes the modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.[25]

Pre-Islamic era

After Alexander's death in 323 BCE, Porus obtained possession of the region but was murdered by Eudemus in 317 BCE. Eudemus then left the region, and with his departure, Macedonian power collapsed. Sandrocottus (Chandragupta), the founder of the Mauryan dynasty, then declared himself master of the province. His grandson, Ashoka, made Buddhism the dominant religion in ancient Gandhara.[25]

After Ashoka's death the Mauryan empire collapse, just as in the west the Seleucid power was rising. The Greek princes of neighboring Bactria (in modern Afghanistan) took advantage of the power vacuum to declare their independence. The Bactrian kingdoms were then attacked from the west by the Parthians and from the north (about 139 BCE) by the Sakas, a Central Asian tribe. Local Greek rulers still exercised a feeble and precarious power along the borderland, but the last vestige of Greek dominion was extinguished by the arrival of the Yueh-chi.[25]

The Yueh-Chi were a race of nomads that were themselves forced southwards out of Central Asia by the nomadic Xiongnu people. The Kushan clan of the Yuek Chi seized vast swathes of territory under the rule of Kujula Kadphises. His successors, Vima Takto and Vima Kadphises, conquered the north-western portion of the Indian subcontinent. Vima Kadphises was then succeeded by his son, the legendary Buddhist king Kanishka, who himself was succeeded by Huvishka, and Vasudeva I.[25]

Early Islamic Invasions

After the Saffarids had left in Kabul, the Hindu Shahis had once again been placed into power. The restored Hindu Shahi kingdom was founded by the Brahmin minister Kallar in 843 CE. Kallar had moved the capital into Udabandhapura in modern-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa from Kabul. Trade had flourished and many gems, textiles, perfumes, and other goods had been exported West. Coins minted by the Shahis have been found all over the Indian subcontinent. The Shahis had built Hindu temples with many idols, all of which were later looted by invaders. The ruins of these temples can be found at Nandana, Malot, Siv Ganga, and Ketas, as well as across the west bank of the Indus river.[26][27]

At its height King Jayapala, the rule of the Shahi kingdom had extended to Kabul from the West, Bajaur to the North, Multan to the South, and the present day India-Pakistan border to the East.[26] Jayapala saw a danger from the rise to power of the Ghaznavids and invaded their capital city of Ghazni both in the reign of Sebuktigin and in that of his son Mahmud. This had initiated the Muslim Ghaznavid and Hindu Shahi struggles.[28] Sebuktigin, however, defeated him and forced Jayapala to pay an indemnity.[28] Eventually, Jayapala refused payment and took to war once more. The Shahis were decisively defeated by Mahmud of Ghazni after the defeat of Jayapala at the Battle of Peshawar on 27 November 1001.[29] Over time, Mahmud of Ghazni had pushed further into the subcontinent, as far as east as modern day Agra. During his campaigns, many Hindu temples and Buddhist monasteries had been looted and destroyed, as well as many people being converted to Islam.[30]

Following the collapse of Ghaznavid rule, local Pashtuns of the Delhi Sultanate controlled the region. Several Turkic and Pashtun dynasties ruled from Delhi, having shifted their capital from Lahore to Delhi. Several Muslim dynasties ruled modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa during the Delhi Sultanate period: the Mamluk dynasty (1206–90), the Khalji dynasty (1290–1320), the Tughlaq dynasty (1320–1413), the Sayyid dynasty (1414–51), and the Lodi dynasty (1451–1526).

Tanoli tribe of Ghilji confederation from Ghazni Afghanistan came with Sabuktagin and settled in the mountainous area of Hazara called Tanawal (Amb).[31][32][33]

Yusufzai Pashtun tribes from the Kabul and Jalalabad valleys began migrating to the Valley of Peshawar beginning in the 15th century,[34] and displaced the Swatis of bhittani confederation ( a predominant Pashtun tribe of Hazara div ) and Dilazak Pashtun tribes across the Indus River to Hazara Division.[34]

Mughal

Mughal suzerainty over the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region was partially established after Babar, the founder of the Mughal Empire, invaded the region in 1505 CE via the Khyber Pass. The Mughal Empire noted the importance of the region as a weak point in their empire's defenses,[35] and determined to hold Peshawar and Kabul at all cost against any threats from the Uzbek Shaybanids.[35]

He was forced to retreat westwards to Kabul but returned to defeat the Lodis in July 1526, when he captured Peshawar from Daulat Khan Lodi,[36] though the region was never considered to be fully subjugated to the Mughals.[34]

Under the reign of Babar's son, Humayun, a direct Mughal rule was briefly challenged with the rise of the Pashtun Emperor, Sher Shah Suri, who began construction of the famous Grand Trunk Road – which links Kabul, Afghanistan with Chittagong, Bangladesh over 2000 miles to the east. Later, local rulers once again pledged loyalty to the Mughal emperor.

Yusufzai tribes rose against Mughals during the Yusufzai Revolt of 1667,[35] and engaged in pitched-battles with Mughal battalions in Peshawar and Attock.[35] Afridi tribes resisted Aurangzeb rule during the Afridi Revolt of the 1670s.[35] The Afridis massacred a Mughal battalion in the Khyber Pass in 1672 and shut the pass to lucrative trade routes.[37] Following another massacre in the winter of 1673, Mughal armies led by Emperor Aurangzeb himself regained control of the entire area in 1674,[35] and enticed tribal leaders with various awards in order to end the rebellion.[35]

Referred to as the "Father of Pashto Literature" and hailing from the city of Akora Khattak, the warrior-poet Khushal Khan Khattak actively participated in revolt against the Mughals and became renowned for his poems that celebrated the rebellious Pashtun warriors.[35]

Afsharid

On 18 November 1738, Peshawar was captured from the Mughal governor Nawab Nasir Khan by the Afsharid armies during the Persian invasion of the Mughal Empire under Nader Shah.[38][39]

Durrani Afghans

The area fell subsequently under the rule of Ahmad Shah Durrani, founder of the Afghan Durrani Empire,[40] following a grand nine-day long assembly of leaders, known as the loya jirga.[41] In 1749, the Mughal ruler was induced to cede Sindh, the Punjab region and the important trans Indus River to Ahmad Shah in order to save his capital from Afghan attack.[42] In short order, the powerful army brought under its control the Tajik, Hazara, Uzbek, Turkmen, and other tribes of northern Afghanistan. Ahmad Shah invaded the remnants of the Mughal Empire a third time, and then a fourth, consolidating control over the Kashmir and Punjab regions, with Lahore being governed by Afghans. He sacked Delhi in 1757 but permitted the Mughal dynasty to remain in nominal control of the city as long as the ruler acknowledged Ahmad Shah's suzerainty over Punjab, Sindh, and Kashmir. Leaving his second son Timur Shah to safeguard his interests, Ahmad Shah left India to return to Afghanistan.

Their rule was interrupted by a brief invasion of the Hindu Marathas, ruled over the region following the 1758 Battle of Peshawar for eleven months till early 1759 when the Durrani rule was re-established.[43]

Under the reign of Timur Shah, the Mughal practice of using Kabul as a summer capital and Peshawar as a winter capital was reintroduced,[34][44] Peshawar's Bala Hissar Fort served as the residence of Durrani kings during their winter stay in Peshawar.

Mahmud Shah Durrani became king, and quickly sought to seize Peshawar from his half-brother, Shah Shujah Durrani.[45] Shah Shujah was then himself proclaimed king in 1803, and recaptured Peshawar while Mahmud Shah was imprisoned at Bala Hissar fort until his eventual escape.[45] In 1809, the British sent an emissary to the court of Shah Shujah in Peshawar, marking the first diplomatic meeting between the British and Afghans.[45] Mahmud Shah allied himself with the Barakzai Pashtuns, and amassed an army in 1809, and captured Peshawar from his half-brother, Shah Shujah, establishing Mahmud Shah's second reign,[45] which lasted under 1818.

Sikh

Ranjit Singh invaded Peshawar in 1818 but soon lost it to the Afghans.[46] Following the Sikh victory against Azim Khan, half-brother of Emir Dost Mohammad Khan, at the Battle of Nowshera in March 1823, Ranjit Singh captured the Peshawar Valley.[46][46] An 1835 attempt by Dost Muhammad Khan to re-occupy Peshawar failed when his army declined to engage in combat with the Dal Khalsa.[46] Dost Muhammad Khan's son, Mohammad Akbar Khan engaged with Sikh forces the Battle of Jamrud of 1837, and failed to recapture it.

During Sikh rule, an Italian named Paolo Avitabile was appointed an administrator of Peshawar, and is remembered for having unleashed a reign of fear there. The city's famous Mahabat Khan, built in 1630 in the Jeweler's Bazaar, was badly damaged and desecrated by the Sikhs,[47] who also rebuilt the Bala Hissar fort during their occupation of Peshawar.[45]

British Raj

British East India Company defeated the Sikhs during the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, and incorporated small parts of the region into the Province of Punjab. While Peshawar was the site of a small revolt against British during the Mutiny of 1857, local Pashtun tribes throughout the region generally remained neutral or supportive of the British as they detested the Sikhs,[22] in contrast to other parts of British India which rose up in revolt against the British. However, British control of parts of the region was routinely challenged by Wazir tribesmen in Waziristan and other Pashtun tribes, who resisted any foreign occupation until Pakistan was created. By the late 19th century, the official boundaries of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region still had not been defined as the region was still claimed by the Kingdom of Afghanistan. It was only in 1893 The British demarcated the boundary with Afghanistan under a treaty agreed to by the Afghan king, Abdur Rahman Khan, following the Second Anglo-Afghan War.[48] In 1901, the North-West Frontier Province was formally created by the British administration on the British side of the Durand Line, although the princely states of Swat, Dir, Chitral, and Amb were allowed to maintain their autonomy under the terms of maintaining friendly ties with the British. As the British war effort during World War One demanded the reallocation of resources from British India to the European war fronts, some tribesmen from Afghanistan crossed the Durand Line in 1917 to attack British posts in an attempt to gain territory and weaken the legitimacy of the border. The validity of the Durand Line, however, was re-affirmed in 1919 by the Afghan government with the signing of the Treaty of Rawalpindi,[49] which ended the Third Anglo-Afghan War – a war in which Waziri tribesmen allied themselves with the forces of Afghanistan's King Amanullah in their resistance to British rule. The Wazirs and other tribes, taking advantage of instability on the frontier, continued to resist British occupation until 1920 – even after Afghanistan had signed a peace treaty with the British.

British campaigns to subdue tribesmen along the Durand Line, as well as three Anglo-Afghan wars, made travel between Afghanistan and the densely populated heartlands of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa increasingly difficult. The two regions were largely isolated from one another from the start of the Second Anglo-Afghan War in 1878 until the start of World War II in 1939 when conflict along the Afghan frontier largely dissipated. Concurrently, the British continued their large public works projects in the region, and extended the Great Indian Peninsula Railway into the region, which connected the modern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region to the plains of India to the east. Other projects, such as the Attock Bridge, Islamia College University, Khyber Railway, and establishment of cantonments in Peshawar, Kohat, Mardan, and Nowshera further cemented British rule in the region.[50]

During this period, North-West Frontier Province was a "scene of repeated outrages on Hindus."[51] During the independence period there was a Congress-led ministry in the province, which was led by secular Pashtun leaders, including Bacha Khan, who preferred joining India instead of Pakistan. The secular Pashtun leadership was also of the view that if joining India was not an option then they should espouse the cause of an independent ethnic Pashtun state rather than Pakistan.[52] The secular stance of Bacha Khan had driven a wedge between the ulama of the otherwise pro-Congress (and pro-Indian unity) Jamiat Ulema Hind (JUH) and Bacha Khan's Khudai Khidmatgars. The directives of the ulama in the province began to take on communal tones. The ulama saw the Hindus in the province as a 'threat' to Muslims. Accusations of molesting Muslim women were levelled at Hindu shopkeepers in Nowshera, a town where anti-Hindu sermons were delivered by maulvis.

Tensions also rose in 1936 over the abduction of a Hindu girl in Bannu. British Indian court ruled against the marriage of a Hindu-converted Muslim girl at Bannu, after the girl's family filed a case of abduction and forced conversion. The ruling was based on the fact that the girl was a minor and was asked to make her decision of conversion and marriage after she reaches the age of majority, till then she was asked to live with a third party.[53] The verdict 'enraged' the Muslims - especially the Pashtun tribesmen. The Dawar Maliks and mullahs left the Tochi far the Khaisora Valley to the south to rouse the Torikhel Wazir. The enraged tribesmen mustered two large lashkars 10,000 strong and battled the Bannu Brigade, with heavy casualties on both sides. Widespread lawlessness erupted as tribesmen blocked roads, overran outposts and ambushed convoys. The British retaliated by sending two columns converging in the Khaisora river valley. They suppressed the agitation by imposing fines and by destroying the houses of the ringleaders, including that of Haji Mirzali Khan (Faqir of Ipi). However, the pyrrhic nature of the victory and the subsequent withdrawal of the troops was credited by the Wazirs to be a manifestation of the power of Mirzali Khan. He succeeded in inducing a semblance of tribal unity, as the British noticed with dismay, among various sections of Tori Khel Wazirs, the Mahsud and the Bettani. He cemented his position as a religious leader by declaring a Jihad against the British. This move also helped rally support from Pashtun tribesmen across the border.

Such controversies stirred up anti-Hindu sentiments amongst the province's Muslim population.[54] By 1947 the majority of the ulama in the province began supporting the Muslim League's idea of Pakistan.[55]

Bannu Resolution

In June 1947, Mirzali Khan (Faqir of Ipi), Bacha Khan, and other Khudai Khidmatgars declared the Bannu Resolution, demanding that the Pashtuns be given a choice to have an independent state of Pashtunistan composing all Pashtun majority territories of British India, instead of being made to join the new state of Pakistan. However, the British Raj refused to comply with the demand of this resolution, as their departure from the region required regions under their control to choose either to join India or Pakistan, with no third option.[56][57]

By 1947 Pashtun nationalists were advocating for a united India, and no prominent voices advocated for a union with Afghanistan.[58][59]

1947 NWFP referendum

Immediately prior to the 1947 Partition of India, the British held a referendum in the NWFP to allow voters to choose between joining India or Pakistan. The polling began on 6 July 1947 and the referendum results were made public on 20 July 1947. According to the official results, there were 572,798 registered voters, out of which 289,244 (99.02%) votes were cast in favour of Pakistan, while 2,874 (0.98%) were cast in favour of India. The Muslim League declared the results as valid since over half of all eligible voters backed merger with Pakistan.[60]

The then Chief Minister Dr. Khan Sahib, along with his brother Bacha Khan and the Khudai Khidmatgars, boycotted the referendum, citing that it did not have the options of the NWFP becoming independent or joining Afghanistan.[61][62]

Their appeal for boycott had an effect, as according to an estimate, the total turnout for the referendum was 15% lower than the total turnout in the 1946 elections,[63] although over half of all eligible voters backed merger with Pakistan.[60]

Bacha Khan pledged allegiance to the new state of Pakistan in 1947, and thereafter abandoned his goals of an independent Pashtunistan and a united India in favour of supporting increased autonomy for the NWFP under Pakistani rule.[22] He was subsequently arrested by Pakistan several times for his opposition to strong centralized rule.[64] He later claimed that "Pashtunistan was never a reality". The idea of Pashtunistan never helped Pashtuns and it only caused suffering for them. He further claimed that the "successive governments of Afghanistan only exploited the idea for their own political goals".[65]

After the creation of Pakistan

After the creation of Pakistan in 1947, Afghanistan was the sole member of the United Nations to vote against Pakistan's accession to the UN because of Kabul's claim to the Pashtun territories on the Pakistani side of the Durand Line.[66] Afghanistan's Loya Jirga of 1949 declared the Durand Line invalid, which led to border tensions with Pakistan, and decades of mistrust between the two states. Afghan governments have also periodically refused to recognize Pakistan's inheritance of British treaties regarding the region.[67] As had been agreed to by the Afghan government following the Second Anglo-Afghan War and after the treaty ending Third Anglo-Afghan War, no option was available to cede the territory to the Afghans, even though Afghanistan continued to claim the entire region as it was part of the Durrani Empire prior the conquest of the region by the Sikhs in 1818.

In 1950, Afghan-backed separatists in the Waziristan region declared the independence of Pashtunistan as an independent nation o dr the entirety of the NWFP. A Pashtun tribal jirga, held in Razmak, Waziristan, appointed Mirzali Khan as the President of the National Assembly for Pashtunistan. His popularity among the people of Waziristan declined over the years. He died a natural death in 1960 in Gurwek, Waziristan.[68]

Growing participation of Pashtuns in the Pakistani government, however, resulted in the erosion of the support for the secessionist Pashtunistan movement by the end of the 1960s.[69]

All the princely states within the boundaries of the NWFP were allowed to maintain certain autonomy following independence in 1947, but In 1969, the autonomous princely states of Swat, Dir, Chitral, and Amb were fully merged into the province.

For travelers, the area remained relatively peaceful in the 1960s and '70s. It was the usual route on the Hippie trail overland from Europe to India, with buses running from Kabul to Peshawar.[70] While waiting to cross at the border visitors were however cautioned not to stray from the main road.

As a result of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, over five million Afghan refugees poured into Pakistan, mostly choosing to reside in the NWFP (as of 2007, nearly 3 million remained). The North-West Frontier Province became a base for the Afghan resistance fighters and the Deobandi ulama of the province played a significant role in the Afghan 'jihad', with Madrasa Haqqaniyya becoming a prominent organisational and networking base for the anti-Soviet Afghan fighters.[71] The province remained heavily influenced by events in Afghanistan thereafter. The 1989–1992 Civil war in Afghanistan following the withdrawal of Soviet forces led to the rise of the Afghan Taliban, which had emerged in the border region between Afghanistan, Balochistan, and FATA as a formidable political force.

In 2010, the province was renamed "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa." Protests arose among the local Hindkowan, Chitrali, Kohistani and Kalash populations over the name change, as they began to demand their own provinces. The Hindkowans, Kohistanis and Chitralis are last remains of ancient Gandhari people and they jointly protested for preservation of their culture. Seven people were killed and 100 injured in protests on 11 April 2011.[72] The Awami National Party sought to rename the province "Pakhtunkhwa", which translates to "Land of Pashtuns" in the Pashto language. The name change was largely opposed by non-Pashtuns, and by political parties such as the Pakistan Muslim League-N, who draw much of their support from non-Pashtun regions of the province, and by the Islamist Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal coalition.

War and militancy

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has been a site of militancy and terrorism that started after the attacks of 11 September 2001, and intensified when the Pakistani Taliban began an attempt to seize power in Pakistan starting in 2004. Armed conflict began in 2004, when tensions, rooted in the Pakistan Army's search for al-Qaeda fighters in Pakistan's mountainous Waziristan area (in the Federally Administered Tribal Areas), escalated into armed resistance.[73]

Fighting is ongoing between the Pakistani Army and armed militant groups such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Jundallah, Lashkar-e-Islam (LeI), Tehreek-e-Nafaz-e-Shariat-e-Mohammadi (TNSM), al-Qaeda, and elements of organized crime[74][75][76] have led to the deaths of over 50,000 Pakistanis since the country joined the U.S-led War on Terror,[77] with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa being the site of most of the conflict.

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is also the main theater for Pakistan's Zarb-e-Azb operation – a broad military campaign against militants located in the province, and neighboring FATA. By 2014, casualty rates in the country as a whole dropped by 40% as compared to 2011–2013, with even greater drops noted in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa,[78] despite the province being the site of a large massacre of schoolchildren by terrorists in December 2014.

Geography

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa sits primarily on the Iranian plateau and comprises the junction where the slopes of the Hindu Kush mountains on the Eurasian plate give way to the Indus-watered hills approaching South Asia. This situation has led to seismic activity in the past.[79] The famous Khyber Pass links the province to Afghanistan, while the Kohalla Bridge in Circle Bakote Abbottabad is a major crossing point over the Jhelum River in the east.

Geographically the province could be divided into two zones: the northern one extending from the ranges of the Hindu Kush to the borders of Peshawar basin and the southern one extending from Peshawar to the Derajat basin.

The northern zone is cold and snowy in winters with heavy rainfall and pleasant summers with the exception of Peshawar basin, which is hot in summer and cold in winter. It has moderate rainfall.

The southern zone is arid with hot summers and relatively cold winters and scanty rainfall.[80] The Sheikh Badin Hills, a spur of clay and sandstone hills that stretch east from the Sulaiman Mountains to the Indus River, separates Dera Ismail Khan District from the Marwat plains of the Lakki Marwat. The highest peak in the range is the limestone Sheikh Badin Mountain, which is protected by the Sheikh Badin National Park. Near the Indus River, terminus of the Sheikh Badin Hills is a spur of limestone hills known as the Kafir Kot hills, where the ancient Hindu complex of Kafir Kot is located.[81]

The major rivers that criss-cross the province are the Kabul, Swat, Chitral, Kunar, Siran, Panjkora, Bara, Kurram, Dor, Haroo, Gomal and Zhob.

Its snow-capped peaks and lush green valleys of unusual beauty have enormous potential for tourism.[82]

Climate

The climate of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa varies immensely for a region of its size, encompassing most of the many climate types found in Pakistan. The province stretching southwards from the Baroghil Pass in the Hindu Kush covers almost six degrees of latitude; it is mainly a mountainous region. Dera Ismail Khan is one of the hottest places in South Asia while in the mountains to the north the weather is mild in the summer and intensely cold in the winter. The air is generally very dry; consequently, the daily and annual range of temperature is quite large.[83]

Rainfall also varies widely. Although large parts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are typically dry, the province also contains the wettest parts of Pakistan in its eastern fringe specially in monsoon season from mid June to mid September.

Chitral District

Chitral District lies completely sheltered from the monsoon that controls the weather in eastern Pakistan, owing to its relatively westerly location and the shielding effect of the Nanga Parbat massif. In many ways, Chitral District has more in common regarding climate with Central Asia than South Asia.[84] The winters are generally cold even in the valleys, and heavy snow during the winter blocks passes and isolates the region. In the valleys, however, summers can be hotter than on the windward side of the mountains due to lower cloud cover: Chitral can reach 40 °C (104 °F) frequently during this period.[85] However, the humidity is extremely low during these hot spells and, as a result the summer climate is less torrid than in the rest of the Indian subcontinent.

Most precipitation falls as thunderstorms or snow during winter and spring, so that the climate at the lowest elevations is classed as Mediterranean (Csa), continental Mediterranean (Dsa) or semi-arid (BSk). Summers are extremely dry in the north of Chitral district and receive only a little rain in the south around Drosh.

At elevations above 5,000 metres (16,400 ft), as much as a third of the snow which feeds the large Karakoram and Hindukush glaciers comes from the monsoon since these elevations are too high to be shielded from its moisture.[84]

Central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

| Dir | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On the southern flanks of Nanga Parbat and in Upper and Lower Dir Districts, rainfall is much heavier than further north because moist winds from the Arabian Sea are able to penetrate the region. When they collide with the mountain slopes, winter depressions provide heavy precipitation. The monsoon, although short, is generally powerful. As a result, the southern slopes of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are the wettest part of Pakistan. Annual rainfall ranges from around 500 millimetres (20 in) in the most sheltered areas to as much as 1,750 millimetres (69 in) in parts of Abbottabad and Mansehra Districts.

This region's climate is classed at lower elevations as humid subtropical (Cfa in the west; Cwa in the east); whilst at higher elevations with a southerly aspect, it becomes classed as humid continental (Dfb). However, accurate data for altitudes above 2,000 metres (6,560 ft) are practically nonexistent here, in Chitral, or in the south of the province.

| Dera Ismail Khan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The seasonality of rainfall in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa shows very marked gradients from east to west. At Dir, March remains the wettest month due to frequent frontal cloud-bands, whereas in Hazara more than half the rainfall comes from the monsoon.[88] This creates a unique situation characterized by a bimodal rainfall regime, which extends into the southern part of the province described below.[88]

Since cold air from the Siberian High loses its chilling capacity upon crossing the vast Karakoram and Himalaya ranges, winters in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are somewhat milder than in Chitral. Snow remains very frequent at high altitudes but rarely lasts long on the ground in the major towns and agricultural valleys. Outside of winter, temperatures in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are not so hot as in Chitral.

Significantly higher humidity when the monsoon is active means that heat discomfort can be greater. However, even during the most humid periods the high altitudes typically allow for some relief from the heat overnight.[89]

Southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

As one moves further away from the foothills of the Himalaya and Karakoram ranges, the climate changes from the humid subtropical climate of the foothills to the typically arid climate of Sindh, Balochistan and southern Punjab. As in central Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the seasonality of precipitation shows a very sharp gradient from west to east, but the whole region very rarely receives significant monsoon rainfall. Even at high elevations, annual rainfall is less than 400 millimetres (16 in) and in some places as little as 200 millimetres (8 in).

Temperatures in southern Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are extremely hot: Dera Ismail Khan in the southernmost district of the province is known as one of the hottest places in the world with temperatures known to have reached 50 °C (122 °F). In the cooler months, nights can be cold and frosts remain frequent; snow is very rare, and daytime temperatures remain comfortably warm with abundant sunshine.

National parks

There are about 29 National Parks in Pakistan and about 18 in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa.

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 5,888,550 | — |

| 1961 | 7,578,186 | +2.55% |

| 1972 | 10,879,781 | +3.34% |

| 1981 | 13,259,875 | +2.22% |

| 1998 | 20,919,976 | +2.72% |

| 2017 | 35,525,047 | +2.83% |

| Source: [90] | ||

The province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa had a population of 35.53 million at the time of the 2017 Census of Pakistan. The largest ethnic group is the Pashtun, who historically have been living in the areas for centuries.[91] Around 1.5 million Afghan refugees also remain in the province,[92] the majority of whom are Pashtuns followed by Tajiks, Hazaras, Gujjar and other smaller groups. Despite having lived in the province for over two decades, they are registered as citizens of Afghanistan.[93]

The Pashtuns of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa observe tribal code of conduct called Pakhtunwali which has four high value components called nang (honor), badal (revenge), melmastiya (hospitality) and nanawata (rights to refuge).[5]

Languages

Urdu, being the national and official language, serves as a lingua franca for inter-ethnic communications, and sometime Pashto and Urdu are the second and third languages among communities which speak other ethnic languages.[5] In 2011 the provincial government approved in principle the introduction of the five regional languages of Pashto, Hindko, Saraiki, Khowar and Kohistani as compulsory subjects for the schools in the areas where they are spoken.[95]

Religion

The majority of the residents of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa overwhelmingly follows and professes the Sunni principles of Islam while the small followers of Shia principles of Islam are found among the Isma'ilis in the Chitral district.[26] The tribe of Kalasha in southern Chitral still retain an ancient form of Hinduism mixed with Animism.[26] There are very small numbers of residents who are the adherents of Roman Catholicism denomination of Christianity, Hinduism and Sikhism.[96][97]

Government and politics

- Political leanings and the Legislative branch

The Provincial Assembly is a unicameral legislature, which consists of 145 members elected to serve for a constitutionally bounded term of five years. Historically, the province perceived to be a stronghold of the Awami National Party (ANP); a pro-Russian, by procommunist, left-wing and nationalist party.[98][99] Since the 1970s, the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) also enjoyed considerable support in the province due to its socialist agenda.[98] Khyber Pakhtunkhwa was thought to be another leftist region of the country after Sindh.[99]

After the nationwide general elections held in 2002, a plurality voting swing in the province elected one of Pakistan's only religiously-based provincial governments led by the ultra-conservative Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA) during the administration of President Pervez Musharraf. The American involvement in neighboring Afghanistan contributed towards the electoral victory of the Islamic coalition led by Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan (JeI) whose social policies made the province a ground-swell of anti-Americanism.[100] The electoral victory of MMA was also in context of guided democracy in the Musharraff administration that barred the mainstream political parties, the leftist Pakistan Peoples Party and the centre-right Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML(N)), whose chairmen and presidents having been barred from participation in the elections.[101]

Policy enforcement of a range of social restrictions, though the implementation of strict Shariah was introduced by the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal government but the law was never fully enacted due to objections of the Governor of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa backed by the Musharraff administration.[100] Restrictions on public musical performances were introduced, as well as a ban prohibiting music to be played in public places as part of the "Prohibition of Dancing and Music Bill, 2005" – which led to the creation of a thriving underground music scene in Peshawar.[102] The Islamist government also attempted to enforce compulsory hijab on women,[103] and wished to enforce gender segregation in the province's educational institutions.[103] The coalition further tried to prohibit male doctors from performing ultrasounds on women,[103] and tried to close the province's cinemas.[103] In 2005, the coalition successfully passed the "Prohibition of Use of Women in Photograph Bill, 2005," leading to the removal of all public advertisements that featured women.[104]

At the height of Taliban insurgency in Pakistan, the religious coalition lost its grip in the general elections held in 2008, and the religious coalition was swept out of power by the leftist Awami National Party which also witnessed the resignation of President Musharraf in 2008.[100] The ANP government eventually led the initiatives to repeal the major Islamist's social programs, with the backing of the federal government led by PPP in Islamabad.[105] Public disapproval of ANP's leftist program integrated in civil administration with the sounded allegations of corruption as well as popular opposition against religious program promoted by the MMA swiftly shifted the province's leniency towards the right-wing spectrum led by the PTI in 2012.[98] In 2013, the provincial politics shifted towards the right wing, national conservatism when the PTI, led by Imran Khan, was able to form the minority government in coalition with the JeI; the province now serves as the stronghold of the rightist PTI and is perceived as right-wing spectrum of the country.[106]

In non-Pashtun areas, such as Abbottabad, and Hazara Division, the PML(N), the centre-right party, enjoys considerable public support over economical and public policy issues and has a substantial vote bank.[106]

- Executive Branch

The executive branch of the Kyber Pakhtunkhwa is led by the Chief Minister elected by popular vote in the Provincial assembly[107] while the Governor, a ceremonial figure representing the federal government in Islamabad, is appointed from the necessary advice of the Prime Minister of Pakistan by the President of Pakistan.[108]

The provincial cabinet is then appointed by the Chief Minister who takes the Oath of office from the Governor.[109] In matters of civil administration, the Chief Secretary assists the Chief Minister on executing its right to ensure the writ of the government and the constitution.[26][110]

- Judicial Branch

The Peshawar High Court is the province's highest court of law whose judges are appointed by the approval of the Supreme Judicial Council in Islamabad, interpreting the laws and overturn those they find unconstitutional.

Administrative divisions and districts

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa is divided into seven Divisions – Bannu, Dera Ismail Khan, Hazara, Kohat, Malakand, Mardan, and Peshawar. Each division is split up into anywhere between two and nine districts, and there are 35 districts in the entire province. Below you can find a list showing each district ordered by alphabetical order. A full list showing different characteristics of each district, such as their population, area, and a map showing their location can be found at the main article.

- Abbottabad District

- Bajaur District

- Bannu District

- Batagram District

- Buner District

- Charsadda District

- Dera Ismail Khan District

- Hangu District

- Haripur District

- Karak District

- Khyber District

- Kohat District

- Kolai-Palas District

- Kurram District

- Lakki Marwat District

- Lower Chitral District

- Lower Dir District

- Lower Kohistan District

- Malakand District

- Mansehra District

- Mardan District

- Mohmand District

- North Waziristan District

- Nowshera District

- Orakzai District

- Peshawar District

- South Waziristan District

- Swabi District

- Swat District

- Shangla District

- Tank District

- Tor Ghar District

- Upper Chitral District

- Upper Dir District

- Upper Kohistan District

Major cities

Peshawar is the capital and largest city of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. The city is the most populous and comprises more than one-eighth of the province's population and Bannu NA35 is the largest NA Seat of the province.

Economy

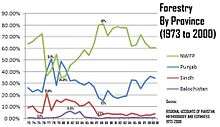

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has the third largest provincial economy in Pakistan. Khyber Pakhtunkhwa's share of Pakistan's GDP has historically comprised 10.5%, although the province accounts for 11.9% of Pakistan's total population. The part of the economy that Khyber Pakhtunkhwa dominates is forestry, where its share has historically ranged from a low of 34.9% to a high of 81%, giving an average of 61.56%.[111] Currently, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa accounts for 10% of Pakistan's GDP,[112] 20% of Pakistan's mining output[113] and, since 1972, it has seen its economy grow in size by 3.6 times.[114]

Agriculture remains important and the main cash crops include wheat, maize, tobacco (in Swabi), rice, sugar beets, as well as fruits are grown in the province.

Some manufacturing and high tech investments in Peshawar has helped improve job prospects for many locals, while trade in the province involves nearly every product. The bazaars in the province are renowned throughout Pakistan. Unemployment has been reduced due to establishment of industrial zones.

Workshops throughout the province support the manufacture of small arms and weapons. The province accounts for at least 78% of the marble production in Pakistan.[115]

Infrastructure

The Sharmai Hydropower Project is a proposed power generation project located in Upper Dir District of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa on the Panjkora River with an installed capacity of 150MW.[116] The project feasibility study was carried out by Japanese consulting company Nippon Koei.

Social issues

The Awami National Party sought to rename the province "Pakhtunkhwa", which translates to "Land of Pakhtuns" in the Pashto language.[117] This was opposed by some of the non-Pashtuns, and especially by parties such as the Pakistan Muslim League-N (PML-N) and Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal (MMA). The PML-N derives its support in the province from primarily non-Pashtun Hazara regions.

In 2010 the announcement that the province would have a new name led to a wave of protests in the Hazara region.[118] On 15 April 2010 Pakistan's senate officially named the province "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa" with 80 senators in favour and 12 opposed.[119] The MMA, who until the elections of 2008 had a majority in the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa government, had proposed "Afghania" as a compromise name.[120]

After the 2008 general election, the Awami National Party formed a coalition provincial government with the Pakistan Peoples Party.[121] The Awami National Party has its strongholds in the Pashtun areas of Pakistan, particularly in the Peshawar valley, while Karachi in Sindh has one of the largest Pashtun populations in the world—around 7 million by some estimates.[122] In the 2008 election, the ANP won two Sindh assembly seats in Karachi. The Awami National Parbeen instrumental in fighting the Taliban. In the 2013 general election Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf won a majority in the provincial assembly and has now formed their government in coalition with Jamaat-e-Islami Pakistan.[123]

Non-government organisations

The following is a list of some of the major NGOs working in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa:[124][125]

- Al-Khidmat Foundation

- Aurat Foundation

- Shaukat Khanum Memorial Cancer Hospital & Research Centre

- Sarhad Rural Support Programme

- Human Rights Commission of Pakistan and

- Global Educational, Economic and Social Empowerment (GEESE)

Folk music and culture

Hindko and Pashto folk music are popular in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and have a rich tradition going back hundreds of years. The main instruments are the rubab, mangey and harmonium. Khowar folk music is popular in Chitral and northern Swat. The tunes of Khowar music are very different from those of Pashto, and the main instrument is the Chitrali sitar. A form of band music composed of clarinets (Surnai) and drums is popular in Chitral. It is played at polo matches and dances. The same form of band music is played in the neighbouring Northern Areas.[126]

Education

| Year | Literacy rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 15.5% |

| 1981 | 16.7% |

| 1998 | 35.41% |

| 2012 | 60.9% |

| 2015 | 88.6% |

This is a chart of the education market of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa estimated[129] by the government in 1998.[130]

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrolment ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Below primary | 413,782 | 3,252,278 | 3,666,060 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 741,035 | 4,646,111 | 5,387,146 | 79.33 |

| Middle | 613,188 | 2,911,563 | 3,524,751 | 48.97 |

| Matriculation | 647,919 | 2,573,798 | 3,221,717 | 29.11 |

| Intermediate | 272,761 | 728,628 | 1,001,389 | 10.95 |

| BA, BSc ... degrees | 20,359 | 42,773 | 63,132 | 5.31 |

| MA, MSc ... degrees | 18,237 | 35,989 | 53,226 | 4.95 |

| Diploma, Certificate ... | 82,037 | 165,195 | 247,232 | 1.92 |

| Other qualifications | 19,766 | 75,226 | 94,992 | 0.53 |

| — | 2,994,084 | 14,749,561 | 17,743,645 | — |

Public Medical colleges

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) province has 9 government medical colleges

- Khyber Medical University, Peshawar

- Bannu Medical College, Bannu

- Khyber Girls Medical College, Peshawar

- Ayub Medical College, Abbottabad

- Bacha Khan Medical College, Mardan

- Gajju Khan Medical College Swabi

- Gomal Medical College, D.I.Khan

- Nowshera Medical College, Nowshera

- Saidu Medical College Swat

Engineering Universities

- CECOS University of Information Technology and Emerging Science, Peshawar

- National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad- College of Aeronautical Engineering, Risalpur Campus

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Islamabad (Abbottabad Campus)

- City University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar

- Gandhara Institute of Science & Technology, PGS Engineering College (University of Engineering & Technology, Peshawar)

- Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences and Technology, Topi-Swabi

- Iqra University Peshawar (Formerly Iqra University, Karachi (Peshawar Campus)

- National University of Sciences and Technology, Islamabad- Military College of Engineering, Risalpur Campus

- National University of Computer & Emerging Sciences, Islamabad (Peshawar Campus)

- University of Engineering & Technology, Peshawar (Main Campus)

- University of Engineering and Technology, Peshawar (Mardan Campus)

- University of Engineering & Technology, Peshawar (Bannu Campus)

- University of Engineering & Technology, Peshawar (Abbottabad Campus)

- University of Engineering & Technology, Peshawar (Kohat Campus)

- Sarhad University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar

- Abasyn University, Peshawar

- University of Science and Technology, Bannu

Major educational establishments

- Cadet College Razmak,NWA

- Abbottabad Public School, Abbottabad

- Akram Khan Durrani College, Bannu

- Cadet College Kohat, Kohat

- Edwardes College, Peshawar

- Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan, Mardan

- Gomal University, Dera Ismail Khan

- Islamia College University, Peshawar

- University of Agriculture, Peshawar

- University of Malakand, Chakdara

- University of Peshawar, Peshawar

Sports

Cricket is the main sport played in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. It has produced world-class sportsmen like Shahid Afridi, Younis Khan, Fakhar Zaman and Umar Gul. Besides producing cricket players, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa has the honour of being the birthplace of many world-class squash players, including greats like Hashim Khan, Qamar Zaman, Jahangir Khan and Jansher Khan.

Tourism

See also

Notes

- Including Population of FATA Which is Merged into Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in 2018.

References

- "Iqbal Zafar Jhagra named new KP governor". DailyTimes. Retrieved 25 February 2016.

- "Dr Niaz made KP chief secretary". TheNation. Retrieved 27 February 2020.

- "PROVISIONAL SUMMARY RESULTS OF 6TH POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS-2017". www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 30 August 2017.

- "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 14 March 2020.

- Claus, Peter J.; Diamond, Sarah; Ann Mills, Margaret (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Taylor & Francis. p. 447. ISBN 9780415939195.

- Rafi U. Samad, The Grandeur of Gandhara: The Ancient Buddhist Civilization of the Swat, Peshawar, Kabul and Indus Valleys. Algora Publishing, 2011. ISBN 0875868592

- "Federal cabinet approves FATA's merger with K-P, repeal of FCR – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 2 March 2017.

- "In Pakistan, Long-Suffering Pashtuns Find Their Voice". The New York Times. 6 February 2018. Retrieved 7 February 2018.

- Wasim, Amir (24 May 2018). "National Assembly green-lights Fata-KP merger by passing 'historic' bill". Dawn. Pakistan Herald Publications. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Hayat, Arif (27 May 2018). "KP Assembly approves landmark bill merging Fata with province". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- "President signs Fata-KP merger bill into law". The Nation. 1 June 2018. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- "Pre=President signs amendment bill, merging FATA with KP". Geo News. Retrieved 15 June 2018.

- U.S. Department of State (2011). Background Notes: South Asia, May, 2011. InfoStrategist.com. ISBN 978-1592431298.

- Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (1997). The evolution and growth of communism in Afghanistan, 1917–79: an appraisal. Royal Book Co. p. XXXV.

- Barnes, Robert Harrison; Gray, Andrew; Kingsbury, Benedict (1995). Indigenous peoples of Asia. Association for Asian Studies. p. 171. ISBN 0924304146.

- Morrison, Cameron (1909). A New Geography of the Indian Empire and Ceylon. T.Nelson and Sons. p. 176.

- Ayers, Alyssa (23 July 2009). Speaking Like a State: Language and Nationalism in Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 61. ISBN 978-0521519311.

- "NWFP in search of a name". pakhtunkhwa.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2016. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- International Centre for Peace Initiatives; Strategic Foresight Group (1 January 2004). Pakistan's provinces. The University of Michigan. p. 53. ISBN 8188262056.

- Roadmap to the Regents: Global History and Geography. Princeton. 2003. p. 80. ISBN 9780375763120.

- Mohiuddin, Yasmeen (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 36. ISBN 9781851098019.

- "KP Historical Overview". Humshehri. Archived from the original on 11 March 2015. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19, page 148 – Imperial Gazetteer of India – Digital South Asia Library". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Bhattacharya, Avijeet. Journeys on the Silk Road Through Ages. Zorba. p. 187.

- "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 19, page 149 – Imperial Gazetteer of India – Digital South Asia Library". Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 52–54.

- Wink, Andre (1991). Al- Hind: The slave kings and the Islamic conquest. E.J Brill. pp. 125.

- P. M. Holt; Ann K. S. Lambton; Bernard Lewis, eds. (1977), The Cambridge history of Islam, Cambridge University Press, p. 3, ISBN 0-521-29137-2,

... Jayapala of Waihind saw danger in the consolidation of the kingdom of Ghazna and decided to destroy it. He therefore invaded Ghazna, but was defeated ...

- "Ameer Nasir-ood-Deen Subooktugeen". Ferishta, History of the Rise of Mohammedan Power in India, Volume 1: Section 15. Packard Humanities Institute. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2012.

- Wynbrandt, James (2009). A Brief History of Pakistan. New York: Infobase Publishing. pp. 52–55.

- Allen, Charles (2012). Soldier Sahibs: The Men Who Made the North-West Frontier. Hachette. p. 96. ISBN 9781848547209.

- Syed Murad Ali,"Tarikh-e-Tanawaliyan"(Urdu), Pub. Lahore, 1975, pp.84

- Ghulam Nabi Khan"Alafghan Tanoli"(Urdu), Pub. Rawalpindi, 2001, pp.244

- Bosworth, Clifford Edmund (2007). Historic Cities of the Islamic World. BRILL. ISBN 9789004153882. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Richards, John F. (1995). The Mughal Empire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521566032. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Henry Miers, Elliot (2013) [1867]. The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108055871.

- Richards, John F. (1996), "Imperial expansion under Aurangzeb 1658–1869. Testing the limits of the empire: the Northwest.", The Mughal Empire, New Cambridge history of India: The Mughals and their contemporaries, 5 (illustrated, reprint ed.), Cambridge University Press, pp. 170–171, ISBN 978-0-521-56603-2

- Sharma, S.R. (1999). Mughal Empire in India: A Systematic Study Including Source Material, Volume 3. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788171568192. Retrieved 24 March 2017.

- Nadiem, Ihsan H. (2007). Peshawar: heritage, history, monuments. Sang-e-Meel. ISBN 9789693519716.

- Alikuzai, Hamid Wahed (October 2013). A Concise History of Afghanistan in 25 Volumes, Volume 14. ISBN 9781490714417. Retrieved 29 December 2014.

- Siddique, Abubakar (2014). The Pashtun Question: The Unresolved Key to the Future of Pakistan and Afghanistan. Hurst. ISBN 9781849044998.

- Meredith L. Runion The History of Afghanistan pp 69 Greenwood Publishing Group, 2007 ISBN 0313337985

- Schofield, Victoria, "Afghan Frontier: Feuding and Fighting in Central Asia", London: Tauris Parke Paperbacks (2003), page 47

- Hanifi, Shah (11 February 2011). Connecting Histories in Afghanistan: Market Relations and State Formation on a Colonial Frontier. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-7777-3. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

Timur Shah transferred the Durrani capital from Qandahar during the period of 1775 and 1776. Kabul and Peshawar then shared time as the dual capital cities of Durrani, the former during the summer and the latter during the winter season.

- Dani, Ahmad Hasan (2003). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: Development in contrast : from the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. UNESCO. ISBN 9789231038761.

- Rai, Jyoti; Singh, Patwant (2008). Empire of the Sikhs: The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. Peter Owen Publishers. ISBN 978-0-7206-1371-1.

- Javed, Asghar (1999–2004). "History of Peshawar". National Fund for Cultural Heritage. National Fund for Cultural Heritage. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- "Country Profile: Afghanistan" (PDF). Library of Congress Country Studies. August 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Robson, Crisis on the Frontier pp. 136–7

- Travel, Culture. "NWFP to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". Travel and culture. Travel and culture. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Elst, Koenraad (2018). "70 (b)". Why I killed the Mahatma: Uncovering Godse's defence. New Delhi : Rupa, 2018.

- Pande, Aparna (2011). Explaining Pakistan's Foreign Policy: Escaping India. Taylor & Francis. p. 66. ISBN 9781136818943.

At Independence there was a Congress-led ministry in the North West Frontier...The Congress-supported government of the North West Frontier led by the secular Pashtun leaders, the Khan brothers, wanted to join India and not Pakistan. If joining India was not an option, then the secular Pashtun leaders espoused the cause of Pashtunistan: an ethnic state for Pashtuns.

- Yousef Aboul-Enein; Basil Aboul-Enein (2013). The Secret War for the Middle East. Naval Institute Press. p. 153. ISBN 978-1612513096.

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 55. JSTOR 27755911.

The stance of the central JUH was pro-Congress, and accordingly the JUS supported the Congressite Khudai Khidmatgars through to the elections of 1937. However the secular stance of Ghaffar Khan, leader of the Khudai Khidmatgars, disparaging the role of religion in government and social leadership, was driving a wedge between the ulama of the JUS and the Khudai Khidmatgars, irrespective of the commitments of mutual support between the JUH and Congress leaderships. In trying to highlight the separateness and vulnerability of Muslims in a religiously diverse public space, the directives of the NWFP ulama began to veer away from simple religious injunctions to take on a communalist tone. The ulama highlighted 'threats' posed by Hindus to Muslims in the province. Accusations of improper behaviour and molestation of Muslim women were levelled against 'Hindu shopkeepers' in Nowshera. Sermons given by two JUS-connected maulvis in Nowshera declared the Hindus the 'enemies' of Islam and Muslims. Posters were distributed in the city warning Muslims not to buy or consume food prepared and sold by Hindus in the bazaars. In 1936, a Hindu girl was abducted by a Muslim in Bannu and then married to him. The government demanded the girl's return, But popular Muslim opinion, supported by a resolution passed by the Jamiyatul Ulama Bannu, demanded that she stay, stating that she had come of her free will, had converted to Islam, and was now lawfully married and had to remain with her husband. Government efforts to retrieve the girl led to accusations of the government being anti-Muslim and of encouraging apostasy, and so stirred up strong anti-Hindu sentiment across the majority Muslim NWFP.

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 57–58. JSTOR 27755911.

By 1947 the majority of NWFP ulama supported the Muslim League idea of Pakistan. Because of the now long-standing relations between JUS ulama and the Muslim League, and the strong communalist tone in the NWFP, the move away from the pro-Congress and anti-Pakistan party line of the central JUH to interest and participation in the creation of Pakistan by the NWFP Deobandis was not a dramatic one.

- Ali Shah, Sayyid Vaqar (1993). Marwat, Fazal-ur-Rahim Khan (ed.). Afghanistan and the Frontier. University of Michigan: Emjay Books International. p. 256.

- H Johnson, Thomas; Zellen, Barry (2014). Culture, Conflict, and Counterinsurgency. Stanford University Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780804789219.

- Harrison, Selig S. "Pakistan: The State of the Union" (PDF). Center for International Policy. pp. 13–14. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Singh, Vipul (2008). The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson. p. 65. ISBN 9788131717530.

- Jeffrey J. Roberts (2003). The Origins of Conflict in Afghanistan. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 108–109. ISBN 9780275978785. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- Karl E. Meyer (5 August 2008). The Dust of Empire: The Race For Mastery In The Asian Heartland. ISBN 9780786724819. Retrieved 25 June 2019.

- "Was Jinnah democratic? — II". Daily Times. 25 December 2011. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Abdul Ghaffar Khan(1958) Pashtun Aw Yoo Unit. Peshawar.

- "Everything in Afghanistan is done in the name of religion: Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan". India Today. Archived from the original on 8 January 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2014.

- "PAKISTAN-AFGHANISTAN RELATIONS IN THE POST-9/11 ERA, October 2006, Frédéric Grare" (PDF). Retrieved 20 November 2013.

- http://www.carnegieendowment.org/files/cp72_grare_final.pdf

- The legendary guerilla Faqir of Ipi unremembered on his 115th anniversary. The Express Tribune. 18 April 2016.

- Rizwan Hussain. Pakistan and the emergence of Islamic militancy in Afghanistan. 2005. p. 74.

- When Afghanistan was just a laid-back highlight on the hippie trail

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 66–67. JSTOR 27755911.

- "Anti-Pakhtunkhwa protest claims 7 lives in Abbottabad". The Statesmen. 13 April 2011. Archived from the original on 24 November 2011. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

- "[Pakistan Primer Pt. 1] The Rise of the Pakistani Taliban Archived 29 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine," Global Bearings, 27 October 2011.

- Varun Vira and Anthony Cordesman "Pakistan: Violence versus Stability: A Net Assessment." Center for Strategic and International Studies, 25 July 2011.

- "The War in Pakistan". The Washington Post. 25 January 2006. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- Zaffar Abbas. "Pakistan's undeclared war". News.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 19 October 2008.

- Shaun Waterman (27 March 2013). "Heavy price: Pakistan says war on terror has cost nearly 50,000 lives there since 9/11". The Washington Times, 2013. Retrieved 16 June 2013.

- "A Small Measure of Progress".

- "Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (province, Pakistan) :: Geography – Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "It's wintertime in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | Newspaper". Dawn.Com. 29 November 2012. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- Tolbort, T (1871). The District of Dera Ismail Khan, Trans-Indus. Retrieved 12 December 2017.

- "Cold weather in upper areas & dry weather observed in almost all parts of the country | PaperPK News about Pakistan". Paperpkads.com. 29 January 2013. Archived from the original on 2 August 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "North-West Frontier Province – Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 19, p. 147". Dsal.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Mock, John and O'Neil, Kimberley; Trekking in the Karakoram and Hindukush; p. 15 ISBN 0-86442-360-8

- Mock and O'Neil; Trekking in the Karakoram and Hindukush; pp. 18–19

- "World Climate Data: Dir, Pakistan". Weatherbase. 2010. Archived from the original on 20 May 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- "World Climate Data: Dera Ismail Khan, Pakistan". Weatherbase. 2010. Archived from the original on 1 January 2011. Retrieved 1 September 2010.

- See Wernsted, Frederick L.; World Climatic Data; published 1972 by Climatic Data Press; 522 pp. 31 cm.

- "Article - Education Resources". www.hko.gov.hk. Retrieved 24 October 2019.

- "Preliminary 2017 census result" (PDF). Pakistan Bureau of Statistics. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- People and culture – Government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

- "Pakistani TV delves into lives of Afghan refugees". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 30 April 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "UNHCR country operations profile – Pakistan". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- Bashir, Elena L. (2016). "Language endangerment and documentation. Pakistan and Afghanistan". In Hock, Hans Henrich; Bashir, Elena L. (eds.). The languages and linguistics of South Asia: a comprehensive guide. World of Linguistics. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. p. 639. ISBN 978-3-11-042715-8.

- "Pakistan Valmiki Sabha". Bhagwanvalmiki.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2004. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- "Sikh refugees demand Indian citizenship". Oneindia News. 24 February 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- Sheikh, Yasir (5 November 2012). "Areas of political influence in Pakistan: right-wing vs left-wing". rugpundits.com. Karachi, Sindh: Rug Pandits, Yasir. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Sheikh, Yasir (9 February 2013). "Political spectrum of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) – Part I: ANP, PPP & MMA". rugpundits.com. Islamabad: Rug Pandits, Yasir Sheikh. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Robinson, Simon (29 February 2008). "Religion's Defeat in Pakistan's Election". Time. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Ali, Kamran Asdar (Summer 2004). "Pakistani Islamists Gamble on the General". Middle East Research and Information Project. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- Tirmizi, Maria; Rizwan-ul-Haq (24 June 2007). "Peshawar underground: It's difficult to be a rock star in the land the epitomises conservatism, yet something shocking is happening. There is a rock scene waiting to burst out of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Rahim Shah was just the beginning, Sajid and Zeeshan were proof that originality can spring out of unlikely places and there are others who are making their riffs and ragas heard... slowly, but surely". The News on Sunday Instep. Archived from the original on 25 August 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- Clarke, Michael E.; Misra, Ashutosh (1 March 2013). Pakistan's Stability Paradox: Domestic, Regional and International Dimensions. Routledge. ISBN 9781136639340. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "PESHAWAR: Advertisers forced to deface billboards". Dawn. 3 May 2006. Retrieved 6 April 2017.

- "Musicians in Pakistan's northwest long for better times". Reuters. 15 March 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2017.

- Sheikh, Yasir. "Rightwing Tsunami: PTI's rise in Pakistani politics". rugpundits.com. rugpundits, Yasir. Archived from the original on 30 May 2015. Retrieved 29 May 2015.

- Article 130(4) in Chapter 3: The Provincial Governments, in Part Part IV: Provinces, of the Constitution of Pakistan

- Article 101(1) in Chapter 1: The Governors, in Part Part IV: Provinces, of the Constitution of Pakistan

- Article 132(2) in Chapter 3: The Provincial Governments, in Part Part IV: Provinces, of the Constitution of Pakistan

- "Government of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa functions". kp.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 10 May 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973–2000" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Roman, David (15 May 2009). "Pakistan's Taliban Fight Threatens Key Economic Zone - WSJ.com". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Pakistan May Need Extra Bailouts as War Hits Economy (Update2)". Bloomberg.com. 15 June 2009. Archived from the original on 13 March 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Pakistan Balochistan Economic Report From Periphery to Core" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "World Bank Pakistan Growth and Export Competitiveness" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- Malik, Arshad Aziz (19 July 2016). "KP govt to face Rs 48.5 bn annual loss due to flawed energy policy". thenews.com.pk. Retrieved 28 January 2017.

- "NWFP to KPK". www.insightonconflict.org.

- "Protest in Hazara continues over renaming of NWFP to Khyber Pakhtunkhwa". App.com.pk. Archived from the original on 9 December 2011. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "NWFP officially renamed as Pakhtun HAZARA". Dawn.com. 15 April 2010. Archived from the original on 18 April 2010. Retrieved 15 April 2010.

- "MMA govt proposes new name for Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (then NWFP)". Dawn. Archived from the original on 13 November 2007.

- Abbas, Hassan. "Peace in FATA: ANP Can Be Counted On." Statesman (Pakistan) (4 February 2007).

- PBS Frontline: Pakistan: Karachi's Invisible Enemy City potent refuge for Taliban fighters. 17 July 2009.

- "Pakistan's 'Gandhi' party takes on Taliban, Al Qaeda". CSMonitor.com. 5 May 2008. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "List of NGOs in KPK- Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (NWFP)". www.ngos.org.pk. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016.

- "Light in dark times: The ABC of empowering women – The Express Tribune". 4 March 2015.

- South Asia: The Indian Subcontinent. (Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 5). Routledge; Har/Com edition (November 1999). ISBN 978-0-8240-4946-1

- "Pakistan: where and who are the world's illiterates?; Background paper for the Education for all global monitoring report 2006: literacy for life; 2005" (PDF). Retrieved 25 May 2010.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 July 2009. Retrieved 13 January 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Population Census Organization, Government of Pakistan". Statpak.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 19 August 2010. Retrieved 25 May 2010.

.jpg)

.jpg)