Package cushioning

Package cushioning is used to protect items during shipment. Vibration and impact shock during shipment and loading/unloading are controlled by cushioning to reduce the chance of product damage.

Cushioning is usually inside a shipping container such as a corrugated box. It is designed to absorb shock by crushing and deforming, and to dampen vibration, rather than transmitting the shock and vibration to the protected item. Depending on the specific situation, package cushioning is often between 50 and 75 millimeters (two to three inches) thick.

Internal packaging materials are also used for functions other than cushioning, such as to immobilize the products in the box and lock them in place, or to fill a void.

Design factors

When designing packaging the choice of cushioning depends on many factors, including but not limited to:

- effective protection of product from shock and vibration

- resilience (whether it performs for multiple impacts)

- resistance to creep – cushion deformation under static load

- material costs

- labor costs and productivity

- effects of temperature,[1] humidity, and air pressure on cushioning

- cleanliness of cushioning (dust, insects, etc.)

- effect on size of external shipping container

- environmental and recycling issues

- sensitivity of product to static electricity

Common types of cushioning

Loose fill – Some cushion products are flowable and are packed loosely around the items in the box. The box is closed to tighten the pack. This includes expanded polystyrene foam pieces (Foam peanuts), similar pieces made of starch-based foams, and common popcorn. The amount of loose fill material required and the transmitted shock levels vary with the specific type of material.[2]

Paper – Paper can be manually or mechanically wadded up and used as a cushioning material. Heavier grades of paper provide more weight-bearing ability than old newspapers. Creped cellulose wadding is also available. (Movers often wrap objects with several layers of Kraft paper or embossed pulp before putting them into boxes.)

Corrugated fiberboard pads – Multi-layer or cut-and-folded shapes of corrugated board can be used as cushions.[3] These structures are designed to crush and deform under shock stress and provide some degree of cushioning. Paperboard composite honeycomb structures are also used for cushioning.[4]

Foam structures – Several types of polymeric foams are used for cushioning. The most common are: Expanded Polystyrene (also Styrofoam), polypropylene, polyethylene, and polyurethane. These can be molded engineered shapes or sheets which are cut and glued into cushion structures. Convoluted (or finger) foams sometimes used [5]. Some degradable foams are also available.[6]

Foam-in-place is another method of using polyurethane foams. These fill the box, fully encapsulating the product to immobilize it. It is also used to form engineered structures.

Molded pulp – Pulp can be molded into shapes suitable for cushioning and for immobilizing products in a package. Molded pulp is made from recycled newsprint and is recyclable.

Inflated products – Bubble wrap consists of sheets of plastic film with enclosed “bubbles” of air. These sheets can be layered or wrapped around items to be shipped. A variety of engineered inflatable air cushions are also available. Note that inflated air pillows used for void-fill are not suited for cushioning.

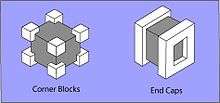

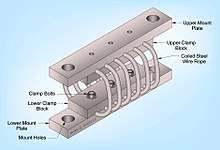

Other – Several other types of cushioning are available including suspension cushions, thermoformed end caps[7] [8] , and various types of shock mounts.

Design for shock protection

Proper performance of cushioning is dependent on its proper design and use. It is often best to use a trained packaging engineer, reputable vendor, consultant, or independent laboratory. An engineer needs to know the severity of shock (drop height, etc.) to protect against. This can be based on an existing specification, published industry standards and publications, field studies, etc.

Knowledge of the product to be packaged is critical. Field experience may indicate the types of damage previously experienced. Laboratory analysis can help quantify the fragility[9] of the item, often reported in g's. Engineering judgment can also be an excellent starting point. Sometimes a product can be made more rugged or can be supported to make it less susceptible to breakage.

The amount of shock transmitted by a particular cushioning material is largely dependent on the thickness of the cushion, the drop height, and the load-bearing area of the cushion (static loading). A cushion must deform under shock for it to function. If a product is on a large load-bearing area, the cushion may not deform and will not cushion the shock. If the load-bearing area is too small, the product may “bottom out” during a shock; the shock is not cushioned. Engineers use “cushion curves” to choose the best thickness and load-bearing area for a cushioning material. Often two to three inches (50 – 75 mm) of cushioning are needed to protect fragile items.

Computer simulations and finite element analysis are also being used. Some correlations to laboratory drop tests have been successful. [10]

Cushion design requires care to prevent shock amplification caused by the cushioned shock pulse duration being close to the natural frequency of the cushioned item.[11]

Design for vibration protection

The process for vibration protection (or isolation) involves similar considerations as that for shock. Cushions can be thought of as performing like springs. Depending on cushion thickness and load-bearing area and on the forcing vibration frequency, the cushion may 1) not have any influence on input vibration, 2) amplify the input vibration at resonance, or 3) isolate the product from the vibration. Proper design is critical for cushion performance.

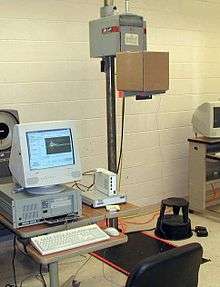

Evaluation of finished package

Verification and validation of prototype designs are required. The design of a package and its cushioning is often an iterative process involving several designs, evaluations, redesigns, etc. Several (ASTM, ISTA, and others) published package testing protocols are available to evaluate the performance of a proposed package. Field performance should be monitored for feedback into the design process.

ASTM Standards

- D1596 Standard Test Method for Dynamic Shock Cushioning Characteristics of Packaging Material

- D2221 Standard Test Method for Creep Properties of Package Cushioning Materials

- D3332 Standard Test Methods for Mechanical-Shock Fragility of Products, Using Shock Machines

- D3580 Standard Test Methods for Vibration (Vertical Linear Motion) Test of Products

- D4168 Standard Test Methods for Transmitted Shock Characteristics of Foam-in-Place Cushioning Materials

- D4169 Standard Practice for Performance Testing of Shipping Containers and Systems

- D6198 Standard Guide for Transport Packaging Design

- D6537 Standard Practice for Instrumented Package Shock Testing For Determination of Package Performance

- and others

See also

- Impact force

- Packaging and labeling

- Shock

- Shock absorber

- Shock response spectrum

- Vibration

- Vibration isolation

- Buffer (disambiguation)

- Damped wave

- Damping

- Damper (disambiguation)

- Betagel, utilizes gel and silicone to absorb violent shocks

Notes

- Hatton, Kayo Okubo (July 1998). Effect of temperature on the cushioning properties of some foamed plastic materials (Thesis). Retrieved 18 Feb 2016.

- Singh, S. P.; Chonhenchob and Burges (1994). "Comparison of Various Loose Fill Cushioning Materials Based on Protective and Environmental Performance". Packaging Technology and Science. 7 (5): 229–241. doi:10.1002/pts.2770070504.

- Stern, R. K.; Jordan, C.A. (1973). "Shock cushioning by corrugated fiberboard pads to centrally applied loading" (PDF). Forest Products Laboratory Research Paper, FPL-RP-184. Retrieved 12 December 2011. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Wang, Dong-Mei; Wang, Zhi-Wei (October 2008). "Experimental investigation into the cushioning properties of honeycomb paperboard". Packaging Technology and Science. 21 (6): 309–373. doi:10.1002/pts.808.

- Burgess, G (1999). "Cushioning properties of convoluted foam". Packaging Technology and Science. 12 (3): 101–104. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1099-1522(199905/06)12:3<101::AID-PTS457>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Mojzes, Akos; Folders, Borocz (2012). "Define Cushion Curves for Environmentally Friendly Foams" (PDF). ANNALS OF FACULTY ENGINEERING HUNEDOARA – International Journal of Engineering: 113–118. Retrieved 8 Mar 2012.

- Khangaldy, Pal; Scheumeman, Herb (2000), Design Parameters for Deformable Cushion Systems (PDF), IoPP, Transpack 2000, retrieved 8 Mar 2012

- US5515976A, Moran, "Packaging for fragile articles within container", published 1996

- Burgess, G (March 2000). "Extensnion and Evaluation of fatigue Model for Product Shock Fragility Used in Package Design". J. Testing and Evaluation. 28 (2).

- Neumayer, Dan (2006), Drop Test Simulation of a Cooker Including Foam, Packaging and Pre-stressed Plastic Foil Wrapping (PDF), 9th International LS-DYNA Users Conference , Simulation Technology (4), retrieved 7 April 2020

- Morris, S A (2011), "Transportation, Distribution, and Product Damage", Food and Package Engineering, Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 367–369, ISBN 978-0-8138-1479-7, retrieved 13 Feb 2015

Further reading

- MIL-HDBK 304C, “Package Cushioning Design”, 1997,

- Russel, P G, and Daum, M P, "Product Protection Test Book", Institute of Packaging Professionals

- Root, D, “Six-Step Method for Cushioned Package Development”, Lansmont, 1997, http://www.lansmont.com/

- Yam, K. L., "Encyclopedia of Packaging Technology", John Wiley & Sons, 2009, ISBN 978-0-470-08704-6

- Singh, J., Ignatova, L., Olsen, E. and Singh, P., "Evaluation of the Stress-Energy Methodology to Predict Transmitted Shock through Expanded Foam Cushions", ASTM Journal of Testing and Evaluation, Volume 38, Issue 6, November 2010