Ostsiedlung

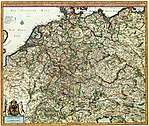

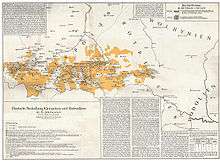

Ostsiedlung (German pronunciation: [ˈɔstˌziːdlʊŋ], literally Eastern settlement) is the term for the process of eastward migration and chartering of settlement structures by ethnic Germans of the Holy Roman Empire into less-populated territories, however, already inhabited by Slavs and Balts east of the Saale and Elbe rivers, primarily the southern and western regions of Eastern Europe and the Baltics. The area of colonization stretched from Estonia at the Baltic coast in the north, via the territories that conform to modern Poland and Silesia, further into Bohemia and Slovenia, Hungary and extended south-east into Transylvania (today in Romania). The Ostsiedlung took place along the roughly 1,000 km (620 mi) long eastern territorial border of the Empire and the State of the Teutonic Order.[1][2] The old term Deutsche Ostkolonisation (German Colonization of the East), which was often used in the past, has been discontinued since the middle of the 20th century due to its linguistic proximity to modern colonialism.[3]

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Germany | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Topics | ||||||||||

| Early history | ||||||||||

| Middle Ages | ||||||||||

| Early Modern period | ||||||||||

| Unification | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| German Reich | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Contemporary Germany | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

Central and Eastern European societies underwent various changes in culture, religion, law and administration, agriculture, demography (settlement numbers and structures) during the period of German eastward expansion. Starting in the 1980s, modern historians have iinterpreted the Ostsiedlung as an element of the process, called Hochmittelalterlicher Landesausbau (High Middle Age Land Consolidation), a pan-European intensification process from the Carolingian-Anglo-Saxon core countries to the periphery of the continent. Contemporary documents do not contain ideas of long-term imperial policies towards organized colonization, neither was there a discernible linear settlement process as immigration took place in many individual efforts and stages, often settlers were encouraged by the Slavic regional lords.[4][5]

Numerous scholars have written extensively on the interaction between the German settlers and local Slav inhabitants. Inevitable ethnic conflicts and local population displacement have been variously interpreted.[6] Some authors claim to have detected systematic expulsion strategies of native populations and in certain areas the existing population was discriminated against and denied participation in administration.[7][8] Modern researchers, however, have concluded that the ethnic patchwork of 12th and 13th century Central and Eastern Europe was far more complex than the ubiquitous Slav-German duality suggests.[9] As total numbers of settlers were rather low and, depending on who locally held a numerical majority, populations usually assimilated into each other.[10]

The migration movement originated in the early Middle Ages. Substantial, yet hardly quantifiable, contingents of immigrants are first documented during the High Middle Ages in the mid 12th century. The purely political and military imperial campaigns during the 11th and 12th centuries are not at all attributable to the eastward expansion, as these actions resulted in not a single noteworthy settlement establishment east of the Elbe and Saale rivers. The Eastern settlement period is considered to have been a purely medieval event as it ended in the beginning of the 14th century. The ethnic, cultural, linguistic and religious as well as economic changes caused by the German Eastern settlement had a profound influence on the history of Eastern Central Europe between the Baltic Sea and the Carpathians until the 20th century.[11]

Background

Central Europe before Eastern expansion

The Carolingian Empire, under which most of Western and Central continental Europe had been united during the 9th century, was partitioned into three parts in 843 as a result of dissent among emperor Charlemagne's three grandsons over the continuation of the custom of partible inheritance or the introduction of primogeniture.[12] Louis the German became sovereign of the Eastern section, East Francia, that included all lands east of the Rhine river and to the north of Italy, which roughly corresponded with the territories of the German stem duchies, that formed a federation under the first king Henry the Fowler (919 to 936).[13]. The Carolingian kings have introduced the establishment of marches (military borderlands) at the periphery of the empire, a tradition that the East Francish and German kings would continue.

Eastern Marches of the Frankish and Holy Roman Empires

The Slavs living within the reach of East Francia (later the Holy Roman Empire) were collectively called Wends or "Elbe Slavs". They seldom formed larger political entities, but rather constituted various small tribes, dwelling as far west as to a line from the Eastern Alps and Bohemia to the Saale and Elbe rivers. As the Frankish Empire expanded, various Wendish tribes were conquered or allied with the Franks, such as the Obotrites, who aided the Franks in defeating the West Germanic Saxons. The conquered Wendish areas were organized by the Franks into marches (German: Marken, meaning "border" or "border lands" in German), which were administered by an entrusted noble who collected the tribute, reinforced by military units. The establishing of marches was also accompanied by missionary efforts.

Marches set up by Charlemagne in the territory where the Ostsiedlung would later take place included, from north to south:

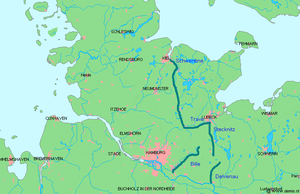

- the Danish march (south of the Danish Danevirke fortifications, between the Eider and Schlei), against the Danes and the Jutes

- the Saxon Eastern March or Nordalbingen March between the Eider and Elbe in what is now Holstein against the Obotrites

- the Thuringian or Sorbian March on the Saale, against the Sorbs dwelling behind the limes sorabicus

- the Franconian march in what is now Upper Franconia, against the Czechs

- the Avar March between the Enns and the Vienna Woods (the later Austrian March), against the Avars

- the March of Pannonia east of Vienna (divided into Upper and Lower)

- the Carantanian march

- the Friaul march

In most cases, the tribes of the marches were not stable allies of the empire. Frankish kings initiated numerous, yet not always successful, military campaigns to maintain their authority.

Later kings and emperors such as Otto I, Holy Roman Emperor, restructured and expanded the marches, creating (from north to south):

- the Billung March on the Baltic Sea, stretching approximately from Groswin to Schleswig

- Marca Geronis (march of Gero), a precursor of the Saxon Eastern March, later divided into smaller marches (the Northern March, which later was re-established as Margraviate of Brandenburg; the March of Lusatia and the Margravate of Meissen in what is now Saxony; the Zeitz March; the Merseburg March; the Milzener March around Bautzen)

- Austrian March (marcha Orientalis, the "Eastern March" or "Bavarian Eastern March" (German: Ostmark) in what is now lower Austria)

- the Carantania or March of Styria

- the Drau March (Maribor and Ptuj)

- the Sann March (Celje)

- the Krain or Carniola march, also Windic March and White Carniola (White March), in what is now Slovenia

Under the rule of King Louis the German of East Francia and of Arnulf of Carinthia, the first waves of settlement were led by Franks and Bavarii, and reached the area of what is today Slovakia and what was then Pannonia (present-day Burgenland, Hungary, and Slovenia). These pioneering settlers were Catholics.

Although the first settlements led by the Franks and Bavarii followed the conquest of the Sorbs and other Wends in the early 10th century, and other campaigns by Holy Roman Emperors made migration possible, the beginning of a continuous Ostsiedlung is usually dated to around the 12th century.

Slavic revolt of 983

In 983, the Polabian Slavs in the Billung and Northern Marches stretching from the Elbe to the Baltic Sea succeeded in a rebellion against the political rule and Christian mission of the Empire. In spite of their new-won independence, the Obotrites, Rani, Liutizian and Hevelli tribes were soon faced with internal struggles and warfare as well as raids from the newly constituted and expanding Piast dynasty (early Polish) state from the east, Denmark from the north and the Empire from the west, eager to reestablish her marches.[14]

Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and Brandenburg

Weakened by ongoing internal conflicts and constant warfare, the independent Wendish territories finally lost the capacity to provide effective military resistance. From 1119 to 1123, Pomerania invaded and subdued the northeastern parts of the Liutizian lands. In 1124 and 1128, Wartislaw I, Duke of Pomerania, at that time a vassal of Poland, invited bishop Otto of Bamberg to Christianize the Pomeranians and Liutizians of his duchy. In 1147, as a campaign of the Northern Crusades, the Wendish Crusade was mounted in the Duchy of Saxony to retake the marches lost in 983. The crusaders also headed for Pomeranian Demmin and Szczecin (Stettin), despite these areas having already been successfully Christianized.

After the Wendish crusade, Albert the Bear was able to establish the Brandenburg march on approximately the territory of former Northern March, which since 983 had been controlled by the Hevelli and Liutizian tribes, and to expand it. The Havelberg bishopric was set up again to Christianize the Wends.

In 1164, after Saxon duke Henry the Lion finally defeated rebellious Obotrites and Pomeranian dukes in the Battle of Verchen, the Pomeranian duchies of Demmin and Stettin became Saxon fiefs, as did the Obodrite territory, which became known as Mecklenburg after its main "burg", fortified settlement. After Henry the Lion lost an internal struggle with Emperor Frederick I, Mecklenburg and Pomerania became part of the Holy Roman Empire in 1181.

Terra Mariana (Livonian Confederation)

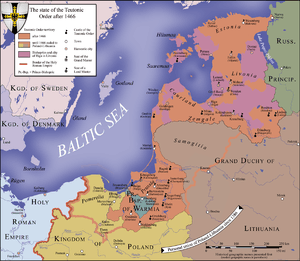

Terra Mariana (Land of Mary) was the official name[15] for Medieval Livonia[16] or Old Livonia [17] (German: Alt-Livland) which was formed in the aftermath of the Livonian Crusade in the territories comprising present day Estonia and Latvia. It was established on February 2, 1207 [18] as a principality of the Holy Roman Empire[19] and proclaimed by Pope Innocent III in 1215 as a subject to the Holy See.[20]

Medieval Livonia was intermittently ruled first by the Livonian Brothers of the Sword, since 1237 by the semi-autonomous Teutonic Order called the Livonian Order and the Catholic Church. The nominal head of Terra Mariana as well as the city of Riga was the Archbishop of Riga as the apex of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.[21]

In 1561, during the Livonian War, Terra Mariana ceased to exist.[15] Its northern parts were ceded to the Swedish Empire and formed into the Duchy of Estonia, its southern territories became part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania — and thus eventually of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth as the Duchy of Livonia and Duchy of Courland and Semigallia. The island of Saaremaa became part of Denmark.

State of the Teutonic Order

From 997, the newly established Piast state in Poland had made attempts to conquer the lands of her northeastern neighbours, the Baltic Old Prussians and Yotvingians. In the early 13th century Konrad of Masovia and Daniel of Halych invited the Teutonic Order to join in Christianizing the Baltic Prussians, who were threatening their lands. During the Northern Crusades the Teutonic Knights conquered the Baltic Prussians and granted themselves the region of Prussia (Altpreussenland) establishing the monastic state there in 1224. With the merger of Livonian Brothers of the Sword in 1237 the Livonian territories were incorporated with the Teutonic Order. In 1308, with the takeover of Danzig (Gdańsk), this state expanded into Pomerelia. In 1346, the Duchy of Estonia was sold by king of Denmark to the Teutonic Order.[22]

Though settlement had to a lower degree occurred in the Frankish marches already, massive settlement did not start until the 12th century (e.g. in East Holstein, West Mecklenburg, Central and Southeastern marches), and in the early 13th century (e.g. in Pomerania, Rügen), following the reassertion of Saxon authority over Wendish areas (the Holstein area by Holstein Count Adolf II, Brandenburg by Albert the Bear, Mecklenburg and Pomerania by Henry the Lion) in the 1150s). The Teutonic monastic state of the Teutonic Order encouraged German settlement of the largely depopulated Prussian lands.

During the Ostsiedlung, German speakers settled east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, regions largely inhabited by Polabian Slavs. Likewise, in Styria and Carinthia, German-speaking communities took form in areas inhabited by Slovenes.

The emigration of inhabitants of the Valais valley in Switzerland to areas that had been settled before by the Romans had to some extent the same preconditions as the colonisation of the East. These so-called Wallisser founded villages in the upper zones of Alp valleys, departing from their valley of origin, throughout the north of Italy, Graubünden (Grisons) and Tyrol.

Rural development

Medieval West European agriculture saw some advances that were carried eastward in the course of the Ostsiedlung.[23] These included:

- the three-field crop rotation, which replaced the ley farming previously common in East Central Europe.[23] According to estimates by Henryk Łowmiański, as cited by Jan Maria Piskorski, this reduced the area of cultivated land needed to feed a family from 35 to 100 hectares (86 to 247 acres) (lay farming) to 4 to 8 hectares (9.9 to 19.8 acres) (three-field system); furthermore the growth of both warm- and cool-season grain increased the likelihood of a good harvest.[23]

- the mouldboard plough with an iron blade, which replaced the scratch plough.[23] While this is stated by Jan Maria Piskorski in a 1997 essay summarizing the state of research, Paweł Zaremba in 1961 said that the mouldboard plough existed already on these territories before the German arrival.[24] However, scratch ploughs remained in use in Livonia until the 19th century and were used in France until that century as well.

- iron spades, scythes and axes[23]

- increased use of horses[23]

- land amelioration techniques such as drainage and dike or levee construction. Sporadic use of fertilizers was likewise introduced.[23]

With the introduction of these techniques, cereals became the primary nutrition, making up for an average 70% of the peoples' calorie intake.[23] As a consequence, an abundance of barns and mills were built.[25] Channels dug for the numerous new watermills marked the first large-scale human interference with the previously untouched water bodies in this area.[25]

The amount of cultivated land also increased, especially through the clearance of forests.[26] The extent of this increase differed by region: while for example in Poland, the area of arable land had doubled (16% of the total area by the beginning of the 11th century and 30% in the 16th century, with the highest increase rates in the 14th century), the area of arable land increased 7- to 20-fold in many Silesian regions during the Ostsiedlung.[26]

The changes in agriculture went along with changes in farm layout and settlement structure based on the Hufenverfassung, a system to divide and classify land.[27] Farmland was divided into Hufen (also Huben, mansi), much like English hides, with one Hufe (25 to 40 hectares depending on the region) plentifully supplying one farm. This led to new types of larger villages, replacing the previously dominant type of small villages consisting of four to eight farms.[25] According to Piskorski (1999), this led to "a complete transformation of the previous settlement structure. The cultural landscape of East Central Europe formed by the medieval settlement processes essentially prevails until today."[25]

Ostsiedlung also led to a rapid population growth throughout East Central Europe.[26] During the 12th and 13th centuries, the population density in persons per square kilometre increased, for example, from two to 20–25 in the area of present-day Saxony, from 6 to 14 in Bohemia, and from 5 to 8.5 in Poland (30 in the Cracow region).[26] In his 1999 essay summarizing the state of research, Piskorski said that the increase was due to the influx of settlers on the one hand and an increase in indigenous populations after the colonization on the other hand: settlement was the primary reason for the increase e.g. in the areas east of the Oder, the Duchy of Pomerania, western Greater Poland, Silesia, Austria, Moravia, Prussia and Transylvania (Siebenbürgen), while in the larger part of Central and Eastern Europe indigenous populations were responsible for the growth.[26] In an essay of 2007, the same Piskorski said that "insofar as it is possible to draw conclusions from the less than rich medieval source material, it appears that at least in some East Central European territories the population increased significantly. It is however possible to contest to what extent this was a direct result of migration and how far it was due to increased agricultural productivity and the gathering pace of urbanization."[28] In contrast to Western Europe, this increased population was largely spared by the 14th-century Black Death pandemic.[26]

With the speakers of a variety of different German dialects also came new systems of taxation. While the Wendish tithe was a fixed tax depending on village size, the German tithe depended on the actual crop, leading to higher taxes being collected from settlers than from the Wends, even though settlers were at least in part exempted from taxes in the first years after the settlement was established. This was a major reason for local rulers' keenness to invite settlers.

Urban development

.jpg)

In the Slavic areas, cities already existed before the Ostsiedlung. Initially craftsmen and merchants formed suburbs of fortified strongholds (grads) or the Wendish-Scandinavian merchants' settlements (emporia) of the Baltic coast. Large cities included Szczecin which reached 9,000 inhabitants and had several temples, Kraków which was the capital of the state of Piast Poland), or Wrocław which already existed with an extensive state administration and church presence. In Poland, the largest cities like Kraków, Gniezno, Wrocław, Wolin counted on average 4,000-5,000 inhabitants each in the beginning of the 12th century.[31] Previous theories that urban development was brought to areas such as Pomerania, Mecklenburg or Poland by Germans during the Ostsiedlung are now discarded, and studies show that towns existed as market places long before arrival of any German colonists, housing Poles and other numerous nationalities.[32][33] Ostsiedlung narrowed the meaning of *gordъ to denote castles only, while towns were thence termed *město (originally "site", compare Polish miast; in areas not affected by Ostsiedlung, the term for town remained a variant of *gordъ, compare Russian город).[34]

The type of town introduced during the Ostsiedlung was called "free town" (civitates liberae) or "new town" by its contemporaries.[25] The rapid increase in the number of towns led, per Piskorski, to an "urbanization of East Central Europe."[25] The new towns differed from their predecessors in:

- The introduction of German town law, resulting in far-reaching administrative and judicial rights for the towns. The townspeople were personally free, enjoyed far-reaching property rights and were subject to the town's own jurisdiction.[25] The privileges granted to the towns were copied, sometimes with minor changes, from the legal charters of Lübeck (Lübeck Law in 33 towns[35] at the southern coast of the Baltic Sea): Magdeburg Law in Brandenburg, areas of modern Saxony, Lusatia, Silesia, northern Bohemia, northern Moravia, Teutonic Order state; Nuremberg Law in southwestern Bohemia; Brünn Law (Brno) in Moravia, based on the charter of Vienna); and Iglau Law (Jihlava) in Bohemian and Moravian mining areas.[36] Besides these basic town laws, several adapted town charters.[36]

- The introduction of permanent markets.[25] While previously, markets were held only periodically, townspeople were now permanently free to trade[25] and marketplaces were a central feature of the new towns.

- Layout: The new towns were planned towns, with their layout often resembling a checkerboard.

- Location: Where towns were not founded on previously empty soil (ex cruda radice, ex nihilo, e.g. Neubrandenburg,[30]), they were—with few exceptions—built a certain distance from a pre-existing castle or early town.[25] Sometimes, as in the case of Brandenburg, the nuclei of the new towns were merchant settlements (usually with a St. Nicholas church) adjacent to Slavic settlements;[36] in other cases, such as Kolberg (now Kołobrzeg), the new town was founded several kilometers away from its predecessor.[25] Where new towns were built in the vicinity of Slavic settlements, the latter continued to exist—its inhabitants usually remained there, or sometimes lived in the new town where they were kept under the force and law of the prince or bishop (both were true for Posen, now Poznań).[37] That way, the princes and bishops kept the services and taxes from the older settlements' inhabitants and did not have to put up with the intricate property rights there.[37] In the few cases where an older settlement was included in the new town, it was, per Piskorski, "surveyed again and built anew" (e.g. Stettin (now Szczecin)).[37]

The corresponding acts of locatio were defined for Poland by Benedykt Zientara as either the actual foundation of a new town, the regularization of a town's layout, and/or the chartering with German town law.[38] Like its rural equivalent, the urban locatio was usually realized by immigrant contractors.[39] These locatores marked out and divided the settlement area, recruited the settlers and assigned them their plots.[39]

Soon after town law was granted and the town area settled, many towns came to care for their own interests much more than for those of the local ruler, and gained partial or full economic and military independence. Many of them joined the Hanseatic League.

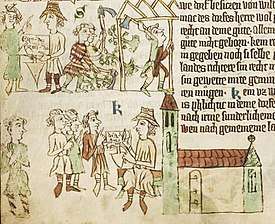

The settlers

The majority of the settlers were speakers of a variety of German dialects. In the northern zones Low German was dominant, in the central zones speakers of Thuringian en Upper-Saxonian participated. In the southern zones speakers of East Frankish and Bavarian dialects were dominant. Significant numbers of Dutch participated, particularly in the early 12th century in the area surrounding the Middle Elbe River.[40] To a lesser extent Danes, Scots or local Wends and (French speaking) Walloons participated as well. The settlers were mostly landless younger children of noble families who could not inherit property. Entrepreneur-adventurers, often from lower-noble descent, called locators, played a recruiting, negotiating and co-ordinating role and established new villages, juridically and geo-physically. Of course, outlaws took the opportunity to escape but they were not appreciated because success depended upon discipline and solidarity.[41]

Settlers were invited by local secular rulers, such as dukes, counts, margraves, princes and (only in a few cases due to the weakening central power) the king. Among them the Slavic dukes (piasts) and kings. Also, settlers were invited by religious institutions such as monasteries and bishops, who had become mighty land-owners in the course of Christian mission. Often, a local secular ruler would grant vast woodlands and wilderness and a few villages to an order like the Cistercian monks, who would erect an abbey, call in settlers and cultivate the land.

The settlers were granted estates and privileges. Settlement was usually organised by a so-called Lokator (allocator of land), who was granted an important position such as the inheritable position of the village elder (Schulte or Schulze). Towns were founded and granted German town law. The agricultural, legal, administrative, and technical methods of the immigrants, as well as their successful proselytising of the native inhabitants, led to a gradual transformation of the settlement areas, as former linguistically and culturally Slavic areas became Germanised.

Besides the marches, which were adjacent to the Empire, German settlement occurred in areas farther away, such as the Carpathians, Transylvania, and along the Gulf of Riga. German cultural and linguistic influence lasted in some of these areas right up to the present day. The rulers of Hungary, Bohemia, Silesia, Pomerania, Mecklenburg, and Poland encouraged German settlement in order to promote the development of the less populated portions of their realms. To provide an incentive to immigrate, the Transylvanian Saxons and Baltic Germans were corporately combined and privileged.

In the middle of the 14th century, the settling progress slowed as a result of the Black Death. Probably the population halved by that time and in addition economically marginal settlements were left, in particular on the sandy soil of Pomerania and Western Prussia. Only after more than a century, local Slavic leaders in late Medieval Pomerania, Western Prussia and Silesia continued inviting German settlers to their territories.

The Thirty Years' War reduced the population of some largely German-speaking lands by a third; e.g., prior to the war, 2.6 million people inhabited the Kingdom of Bohemia; afterwards, there remained only approximately 1.55 million in the kingdom. Nevertheless, as late as the 18th century, some Germans accepted invitations to settle as far away as the southern Ukraine and the slopes of the Volga River. When, in the 17th and 18th centuries, the eastern and southern parts of East Prussia were depopulated by wars and epidemics, colonizers from Germany were no longer available and the Prussian dukes, later on kings, invited Lutheran Austrians, Poles (Mazurians) and Lithuanians to settle in the empty regions. These colonizers largely adopted German customs and language in the 19th and the first half of the 20th century and in this way became associated with the Ostsiedlung.

Assimilation

Colonization was the pretext for assimilation processes that went on for centuries. Assimilation occurred in both directions – depending on the region, either the German speakers, or the local non-Germanic population, was assimilated.

Assimilation of Germans

The Polonization process of Germans who had settled since the 13th century in Poland, in towns like Kraków (Krakau, Cracow) and Poznań (Posen) in the midst of Polish lands, lasted about two centuries. They constituted a patriciate which was not able to continue its isolated position without a continuation of newcomers from German lands. The Sorbs over time also assimilated German settlers in their midst, yet at the same time other Sorbs were themselves assimilated by the surrounding German-speaking population. Many Central and Eastern European towns remained for some centuries multi-ethnic melting pots.[42]

Assimilation, treatment, involvement and traces of the Wends

Although in many areas Slavic population density was not very high compared to the Empire and had even further declined as a result of the extensive warfare during the 10th to 12th centuries, some of the densely settled areas kept their Wendish populations to a varying degree, resisting germanization for a long time.

In the territories of Pomerania and Silesia, German settlers left aside old Wendish villages and built their own new ones on grounds allotted to them by the Slavic nobility and the monasteries. But in the regions west of the Oder, conquered by German nobility or dominated by Slavic nobles who made themselves dependent upon German (Saxon) dukes, there are also documented cases where the Wends were driven out in order to rebuild the village with settlers. In such a case, the new village would nevertheless keep its former Slavic name. As an example, in the case of the village Böbelin in Mecklenburg it is documented that driven-out Wendish inhabitants repeatedly invaded their former village, hindering a resettlement.

In today's Saxony (not to be confused with the old Saxons), the situation was again different as the area and in particular Upper Lusatia was geographically close to Bohemia which itself was ruled by a Slavic dynasty who was a loyal and powerful member of the Roman-German Empire. In this environment, German feudal lords often cooperated with the Slavic inhabitants. A leading figure in early German eastward-migration, Wiprecht of Groitzsch, e.g., only rose to local power by the backing of the Bohemian king and by marriage into Slavic nobility. Thus, the German-Slavic relations there remained largely peaceful. On the other hand, the relation between Slavic-governed Bohemia and Slavic-governed Poland remained one of constant struggle.

Thus, discrimination against the Wends should not be mistaken as part of the general concept of Ostsiedlung. Rather, local Wends were subject to a different taxation level and thus not as profitable as new settlers. This was i.a. the result of the local migration policy which granted tax exemptions as an incentive to those who made land arable and founded new settlements. After such a village had become established, however, standardised German taxes were levied. (See above.) Wends also participated in the development of the area along with German settlers, for new settlers were not sought out just because of their ethnicity, a concept unknown in the Middle Ages, but because of their manpower and agricultural and technical know-how. Thus, they could profit from privileges just the same way as German settlers could do. Even though the majority of the settlers were Germans (Franks and Bavarians in the South, and Saxons and Flemings in the North), Wends and others also participated in the settlement.

Over time, most of the Wends (the general German term for Slavs) were gradually Germanized. However, in isolated rural areas where Wends formed a substantial part of the population, they continued to use Slavic tongues and kept elements of local Wendish culture despite a strong Germanic influx. These were the Drawehnopolaben of the Wendland east of the Lüneburg Heath, the Jabelheide of southern Mecklenburg, the Slovincians and Kashubs of Eastern Pomerania, and the Sorbs of Lusatia. Lusatia was inhabited, from Berlin to Görlitz, by a compact mass of Sorbs until the end of the 19th century. Linguistic assimilation went on in a relatively short time; starting from some 200,000 only a few thousands have remained until today.

Placenames

Where Germans settled and expanded an already existing Slavic settlement, they either kept the Slavic name, translated it, renamed it or assigned a mixed German-Slavic name.[43] In most cases, the Slavic name was kept.[43] Sometimes, the Wends continued to live in a distinct small portion of the village, the Kiez. Where Germans founded a village in the vicinity of an existing Slavic settlement, which decayed afterwards, the new settlement was often named after the nearby Slavic one; seldom was a new name assigned.[43] If the Slavic settlement in the vicinity of the new German one did not decay, the German and Slavic settlements were distinguished by the attributes Deutsch- for the German and Wendisch- for the Slavic one,[43] or Klein- ("little") for the old settlement and Groß- ("large") for the new one. If the German settlement was founded with no Slavic settlement in the vicinity (aus wilder Wurzel, literally "wild rooted"), the name could either be German, the Slavic toponym for the area, or mixed.[43] Slavic-rooted German placenames are not an indicator of preceding Slavic settlements.[44] In some cases, as was shown for some Sudetenland villages, a German and a Slavic placename describing the same settlement co-existed for several centuries.[44]

Where German names were introduced, they usually ended with -dorf or -hagen in the North, and -rode or -hain in the South.[45] Often, the Lokator's name or the region where the settlers originated was made part of the name, too.

Because former Slavic place names were used to name newly established or expanded settlements, many (in many areas even the majority) towns and villages in modern East Germany and the "Former eastern territories of Germany" carried, and in present-day Germany still carry, names with Slavic roots. Most obvious are those names ending with -ow, -vitz or -witz and in many cases -in, including Berlin itself. In the case of the former eastern territories of Germany, these names were Polonized or replaced by new Polish or Russian names after 1945. In Bohemia, Czechoslovakia (re)czechized the German geographical names in the Sudetenland. If possible the former German names were reshaped in a modern linguistic Polish and Czech way. Only originally pure German names are translated or replaced by Polish or Czech counterparts. In the section of East Prussia annexed by the Sovjet Union place names were russified in a drastic way, to start with Kaliningrad as successor of Königsberg, in order to deny any connection with the historical landscape and inhabitants.

In German-speaking areas most inherited surnames were formed only after the Ostsiedlung period, and many surnames derive from the home village or home town of an ancestor, but many German surnames are in fact Germanized Wendish placenames.

The former ethnic difference in German (Deutsch-) and Slavic (Wendisch-, Böhmisch-, Polnisch-) placenames disappeared in the after war Polish and Czech republics. Villages and towns got new or reconstructed Slavic names because the remembrance of the history of colonization and the historical presence of Germans was no longer appreciated by national correctness.

Marches and regions affected

Nordalbingen

The Nordalbingen March, the territory between Hedeby and the Danish fortress of Danevirke in the north and the Elbe river in the south, was part of the empire during the reign of Charlemagne. The border was later fixed at the Eider river.

Saxon Eastern March

While the Franks had already established a Sorbian March east of the Saale river in the 9th century, King Otto I designated a much-larger area the Saxon Eastern March in 937, roughly the territory between the Elbe, the Oder and the Peene rivers. Ruled by Margrave Gero I, it is also referred to as Marca Geronis. After Gero's death in 965, the march was divided in smaller districts: Northern March, Lusatian March, Meissen March, and Zeitz March.

The march was settled by various West Slavic tribes, the most important being Polabian Slavs tribes in the north and Sorbian tribes in the south.

March of the Billungs and the Northern March

The March of the Billungs was constituted simultaneously with the Saxon Eastern March by Otto I in 936. It covered the areas south of the Baltic Sea not in the Eastern March and was put under the rule of Hermann Billung.

The area was inhabited by Obodrites in the West, Rani in the Northeast and Polabian Slavs tribes in the South east.

Due to the great Slavic uprising in 983, both the Billung March and the Northern March were lost for the Empire except for a small area in the West. No substantial Saxon settlement had taken place in the short existence of the marches.

Various efforts were made to re-establish Saxon rule in the territories, the most prominent being the Rethra raiding in 1068 and the Wendish crusade in 1147. Also, there were campaigns of Piast Poland and Denmark into the eastern and northern parts of the area, respectively. Also, local rulers campaigned against each other. Until the final defeat of the Slavs in the 12th century, no Ostsiedlung could take place.

The Northern March was in part re-established as Brandenburg march during the next centuries.

In the 1164 Battle of Verchen the last Obotrite army was defeated by Saxon Henry the Lion. In 1168, the Rani were defeated by the Danes. Mecklenburg, Pomerania and Rügen from now on were under German and Danish overlordship, governed as fiefs by local dynasties of Slavic origin. These dukes called in many German gentry and settlers, adopted Salic law and the Low German language. This is also called the "Second Ostsiedlung", due to the break of some two centuries.

Mecklenburg, Principality of Rügen and Pomerania

After Henry the Lion's defeat, Mecklenburg and Pomerania were turned from Saxon fiefs into direct parts of the Holy Roman Empire by Kaiser Frederick I Barbarossa, while the duchy of Rügen still was Danish. During the next half century, the Empire and Denmark struggled for overlordship in Mecklenburg, Rügen and Pomerania. Most fell to Denmark. Also, the local gentry raised troops to expand their territories. When Denmark lost in the battle of Bornhöved in 1227, all Pomeranian and Mecklenburg areas were again controlled by the Holy Roman Empire.

Despite ongoing border conflicts between the dukes of Pomerania, Mecklenburg, Rügen and Brandenburg, the numbers of German-speaking settlers increased rapidly. Existing and deserted villages and farms were settled up, and new villages were founded, especially by turning the vast woodlands into farmland. Large new German speaking towns replaced the settlements around former Slavic castles, or were founded on unpopulated land. Germans, especially Saxons and Flemings, were attracted by low taxes, cheap or free land, and other privileges. The settlements were organised by locators, often lower nobleman and merchants, who were assigned by the Slavic nobility to plan and settle sites, and in turn, were privileged by public authority as Schulze (burgomasters, aldermen and local judges).

The adoption of Salic law and Germanic culture and the large numbers of settlers as well as replacement or intermarriage of the former Slavic gentry resulted in a completely new organisation and administration of settlements and agriculture. The local Slavic population only in part participated, other parts did not enjoy any benefits and were to settle in separate "Wendish villages", "Wendish streets" or "Wendish quarters". Most of these disappeared in course of the 15th century when these Wends (c.q. Poles and Czechs) were integrated in the (German) mass of the population.

Most of Mecklenburg and Western Pomerania, the northern parts of Farther Pomerania and the mainland section of the duchy of Rügen, were settled by German speakers in the 12th and the beginning of 13th centuries, the other regions of Rügen and Farther Pomerania were settled from 1220 on. In some enclaves, especially in the East of Pomerania, there was only a minor influx of German settlers, so Slavic populations such as the Slovincians, Kashubs persisted.

In Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and Rügen, Ostsiedlung started after the Saxon conquest of 1164. Yet there are only few records of Germans from the 1170s; a large influx of settlers occurred in Eastern Mecklenburg from 1210 on behalf of Duke Heinrich Borwin, in Pomerania after 1220 on behalf of the dukes Wartislaw III (Pomerania-Demmin) and Barnim I (Pomerania-Stettin) as well as the Bishop of Cammin Herrmann von der Gleichen. In the same period, massive settlement began in the mainland section of the Principality of Rügen. The island of Rügen, which was a Slavic stronghold, was settled only in the 14th century.[42]

Hohenkrug near Stettin is the first village clearly recorded as German (villa teutonicorum) in 1173. At the same time, there are records about Germans in the duke's court. Settlement in urban centers is likely to have occurred even earlier (since the 1150s). Stettin's German community had its own church (St. James') erected in 1187.[42]

In Mecklenburg, the first settlers from Holstein and Dithmarschen arrived on the isle of Poel. Since 1220, Ostsiedlung was coordinated by the German knights rather than the Slavic duke. German settlement in its early period focussed on the coastal region with its large woods and only few Slavic settlements. Especially towards the Southeast of Mecklenburg, settlements were established not only by Low German, but also Slavic locators. Here, local Slavs were heavily involved in the settlement process, Germans started to move in since the second half of the 13th century. The settlers originated in the areas west of Mecklenburg (Holstein, Friesland, Lower Saxony, Westphalia), except for the terra Land Stargard, that since 1236 was a part of the Margraviate of Brandenburg and settled by Germans from the Brandenburgian Altmark region.[42]

Pomerania was settled from two directions. The West and the North, including the Principality of Rügen, were settled by people primarily from Mecklenburg, Holstein and Friesland, whereas the South (Stettin area) and the East (parts of Farther Pomerania) were settled primarily by people from the Magdeburg area and Brandenburg. The origins of the Usedom settlers resemble this pattern: Most came from Mecklenburg, the Hanover region and Brandenburg, the others came from Westphalia, Holstein, Friesland, Rhineland, and even Prussia and Poland.[42]

Ostsiedlung in Pomerania and Rügen differed from other settlements by the high proportion of Scandinavians, especially Danes (incl. Scanians). The highest Danish influence was on the Ostsiedlung of the Rugian principality. In the possessions of the Rugian Eldena Abbey, settlers who opened a tavern would respectively be treated according to Danish, German and Wendish law.[42] Wampen and Ladebow and other villages near Greifswald are of Danish origin.[46] Yet, many Scandinavian settlers in the Pomeranian towns were of German origin, moving from the German merchants' settlements in Sweden to the newly founded towns at the Southern Baltic shore.[47]

The evolving large towns of the area—Lübeck, Wismar, Stralsund, Greifswald, Stettin—attracted settlers primarily from Westphalia, Eastphalia, the Low Countries and the Lower Rhine area.[42]

Assimilation and treatment of the Wends varied according to the region and differed between urban and rural areas. In the towns, Wends took part in the settlement, yet were administered separately. In Rostock, Stralsund and Friedland, the Wends were governed by their own Vogt. On the other hand, there are a few records of Wendish patricians, e.g. mentions of a Wendish Ratsherr in Ueckermünde (1284) and Gollnow (1328). The Wends were concentrated in the suburbs, that in some cases were pre-Ostsiedlung Slavic settlements (e.g. in Stettin, where the pre-German town evolved in a Wendish suburb, in which a Wendish public bath is recorded as late as 1350), in other cases newly built settlements (e.g. Greifenhagen-Wiek). In the towns, Wends were subsequently pushed into low-skill professions like dock workers, but there are also records about better situated Wends, who for example dominated pork-and-beef trade in Rostock or ran a bakery in Stettin.[42]

In most of Mecklenburg, Rügen and Pomerania, the Wends were assimilated by the beginning of the 15th century. In the Principality of Rügen, the last Wendish-speaking woman died in 1404 on the Jasmund peninsula. In rural parts of Mecklenburg and Farther Pomerania (east of Köslin) however, Wends are still recorded in the 16th century. Most of the Wends were fishermen, peasants or shepherds, also there were a few Wendish craftsmen.[42]

Brandenburg March

At the time of Albert I, Margrave of Brandenburg (Albrecht "the Bear" von Ballenstedt), the Northern March stretched from the territory of the Askanier (Ascanians, see also Anhalt) to the Markgrafschaft Brandenburg and therefore became part of the Empire. In 1147, Heinrich the Lion conquered the March of the Billungs, the later Mecklenburg as a seignory and in 1164 Pomerania, that lay further to the east of the Baltic Sea. In 1181, Mecklenburg and Pomerania officially became parts of the Holy Roman Empire.

Poland

Rather, the phenomenon involved internal colonization, associated with rural-urban migration by natives, in which many of the Polish cities adopted laws based on those of the German towns of Lubeck and Magdeburg. Some economic methods were likewise imported from Germany.[48][under discussion]

Since the beginning of the 14/15th centuries, the Polish-Silesian Piast dynasty – (Władysław Opolczyk), reinforced German settlers on the land, who in decades founded more than 150 towns and villages under German town law, particularly under the law of the town Magdeburg (Magdeburg law). Ethnic Germans, along with German-speaking Ashkenazi Jews from the Rhineland, also formed a large part of the town population of Kraków.

Concurrent with the change in the structure of the Polish State and sovereignty was an economic and social impoverishment of the country. Harassed by civil strife and foreign invasions, like the Mongol invasion in 1241, the small principalities became enfeebled and depopulated. The incomes of the Princes began to decrease materially. This led them to take steps toward encouraging immigration from foreign countries. A great number of German peasants, who, during the interregnum following the death of Frederick II, suffered great oppression at the hands of their lords, were induced to settle in Poland under very favorable conditions. German immigration into Poland had started spontaneously earlier, about the end of the 11th century, and was the result of overpopulation in the central provinces of the Empire. Advantage of the existing tendency had already been taken by the Polish Princes in the 12th century for the development of cities and crafts. Now the movement became intensified.

Some of studies of the development of the German settlements in Poland indicate that they sprang up along the wide belt which the Mongols laid waste in 1241. It was a stretch of land comprising present Galicia and southern Silesia. Before the Mongol invasion these two provinces were thickly settled and highly developed. Through them ran the commercial highways from the East and the Levant to the Baltic and the west of Europe. Kraków and Wrocław (Breslau) were large and prosperous towns. Some historians, mostly those stressing the scale of German settlements, claim that after the Mongol armies retired the country was in ruins and the population scattered or exterminated. The archaeologist Sebastian Brather claims that the majority of the citizens in Polish and Bohemian towns were of German origin.[49] The theory that newly arrived settlers can be named German has been disputed; for example, Norman Davies in his study on Wrocław, states that such term for people in that era is misleading, as German identity wasn't formed yet.[50] Others, minimizing the effect of German colonisation, minimize the effect of the Mongol invasion, stressing that the destruction was limited mainly to Lesser Poland and mainly the third Mongol invasion. The refugees from this invasion went north and helped to colonize the sparsely inhabited areas and to clear the forests to the east of the Vistula in Mazovia.

The 1257 foundation decree issued by Bolesław V the Chaste for Kraków was unusual insofar that it explicitly separated the local Polish population that already lived in the city,[51] in order to avoid depopulation of already existing settlements that would lead to loss of taxes.[52] Often, the Ostsiedlung settlement was founded near a pre-existing fortress that was within the already existing town, as for example with Poznań (Posen) and Kraków.[53] in order to avoid depopulation of already existing settlements that would lead to loss of taxes.[54]

Pomerelia

In Pomerelia, Ostsiedlung was started by the Pomerelian dukes[55] and focussed on the towns, whereas much of the countryside remained Slavic (Kashubians).[42] An exception was the German settled Vistula delta[42] (Vistula Germans), the coastal regions,[55] and the Vistula valley.[55]

Mestwin II in 1271 referred to the inhabitants of the civitas (town) of Danzig (now Gdańsk) as burgensibus theutonicis fidelibus (to the faithful German burghers).[56]

The settlers came from Low German areas like Holstein, the Low Countries, Flandres, Lower Saxony, Westphalia and Mecklenburg, but a few also from the Middle German Thuringia region.[42]

Silesia

Germans first came to Silesia during the Late Medieval Ostsiedlung.[57] Duchy of Silesia was ruled by the local Piast dynasty. The country at this time was sparsely populated with small hamlets and altogether not more than 150,000 people. Castles with adjacent suburbias were the centre of commerce, administration, crafts and the church. The most important of these cities, most often the seat of a duke, were Wrocław, Legnica, Opole and Racibórz. The country was fortified by the so-called Preseka, a system of dense forests.

The Ostsiedlung in Silesia was initiated by Bolesław I, who spent a part of his life in Germany, and especially by his son Henry I and the latter's wife Hedwig in the late 12th century. They became the first Slavic sovereigns outside of the Holy Roman Empire to promote German settlements on a wide base. Both began to invite German settlers in order to develop their realm economically and to extend their rule. Already in 1175 Bolesław I founded Lubensis abbey and staffed the monastery with German monks from Pforta Abbey in Saxony. Before 1163, the abbey had been inhabited by German Benedictines. The Cistercian abbey, its domain and the German settlers were excluded from local legislation and subsequently the monks founded several German villages on their soil. During Henry I reign the systematic settlement began. In a complex system a network of towns was founded in the western and southwestern parts of Silesia. These towns, economic and judicial centers, were surrounded by standardized built villages which were often constructed on a cleared spot in the forests. The earliest German land clearing area in Silesia appeared from 1147 until 1200 in the area of Złotoryja (Goldberg) and Lwówek Śląski (Löwenberg), two settlements founded by German miners. Goldberg and Löwenberg were also the first Silesian cities to receive German town law in 1211 and 1217. This pattern of colonization was soon adopted in all other, already populated, parts of Silesia, were cities with German town law were often founded beside Slavic settlements.

In the early 14th century Silesia possessed around 150 towns and the population more than quintupled. The townspeople were Germans, which now formed the majority of the overall population, while the Slavs usually lived outside of the cities. In a process of peaceful assimilation Lower and Middle Silesia became organically Germanized on the West bank of Oder while Upper Silesia retained a Slavic majority, although also there German villages, German towns and increasing German agricultural cultivation of barren lands came into existence.

Drang nach Osten

In the 19th century, recognition of this complex phenomenon coupled with the rise of nationalism. This led to a largely unhistoric ethnically inspired nationalist reinterpretation of the medieval process. In Germany and some Slavic countries, most notably Poland, Ostsiedlung was perceived in nationalist circles as a prelude to contemporary expansionism and Germanisation efforts, the slogan used for this perception was Drang nach Osten (Urge to the East).

The German settlement processes in Pomerania did not follow any kind of ideology, nor did the other migratory movements. Rather, the German settlement in Pomerania was shaped exclusively by practical requirements...The national historiography that established itself around the middle of the 19th century retrospectively constructed a Slavic-Germanic contrast in the Ostsiedlung process of the High Middle Ages. However, that was the ideology of the 19th century, not the Middle Ages...Settlement was to be "cuiuscunque gentis et cuiuscunque artis homines" (people of whatever origin and whatever craft,) which was recorded in numerous documents issued by Pomeranian dukes and Rügish princes. -Buchholz[58]

20th century

Economic reasons led to a westward migration of Germans from eastern Prussia in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Ostflucht) (Flight from the East).

Legacy

The 20th century wars and nationalist policies severely altered the ethnic and cultural composition of Central and Eastern Europe. After World War I, Germans in reconstituted Poland were set under pressure to leave the Polish Corridor, the eastern part of Upper Silesia and Poznań. Before World War II, the Nazis initiated the Nazi-Soviet population transfers, wiping out the old settlement areas of the Baltic Germans, the Germans in Bessarabia and others, to resettle them in occupied Poland. Room for them was made during World War II, in line with the Generalplan Ost by expulsion of Poles and enslaving these and other Slavs according to the Nazi's Lebensraum concept. While further realization of this mega plan, aiming at a total reconstitution of Central and Eastern Europe as a German colony, was prevented by the war's turn, the beginning of the expulsion of 2 million Poles and settlement of Volksdeutsche in the annexed territories yet was implied by 1944.

The Potsdam Conference – the meeting between the leaders of the United States, Great Britain, and the Soviet Union – sanctioned the expulsion of Germans from Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary. With the Red Army's advance and Nazi Germany's defeat in 1945, the ethnic make-up of Central and Eastern and East Central Europe was radically changed, as nearly all Germans were expelled not only from all Soviet conquered German settlement areas across Central and Eastern Europe, but also from former territories of the Reich east of the Oder-Neisse line, mainly, the provinces of Silesia, East Prussia, East Brandenburg, and Pomerania. The Soviet-established People's Republic of Poland annexed the majority of the lands while the northern half of East Prussia was taken by the Soviets, becoming the Kaliningrad Oblast, an exclave of the Russian SFSR. The former German settlement areas were resettled by ethnic citizens of the respective succeeding state, (Czechs, Slovaks and Roma in the former Sudetenland and Poles, Lemkos, ethnic Ukrainians in Silesia and Pomerania). However, some areas settled and Germanised in the course of the Ostsiedlung still form the northeastern part of modern Germany, such as the Bundesländer of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Brandenburg, Saxony and east of the limes Saxoniae in Holstein (part of Schleswig-Holstein).

The mediaeval colonization areas, in modern times constituted as the eastern provinces of the German Empire and the Austrian Empire, were inhabited by some 30 million Germans by the beginning of the 20th century. The westward withdrawal of the political boundaries of Germany, partly in 1919, but substantially in 1945, was followed by the removal of some 15 million, to be concentrated within the borders of present-day Germany and Austria. Only the first 12th-century and partially 13th-century colonization areas remained German in language and culture, and this concerns, in a modern political concept, the territory of the pre-1990 German Democratic Republic, and of the eastern part of Austria.

In recent times, dispersed spots and larger concentrations of German colonies throughout all Central and Eastern European states are largely removed by expulsion, assimilation, and emigration.

See also

- Cultural assimilation

- German diaspora

- Drang nach Osten

- Limes Saxoniae

- Barbarian invasions

- Wends

- Wendish Crusade

- Northern Crusades

- Medieval demography

- German exonyms

- Germanisation

- Germanisation of Poles during Partitions

- History of Germans in Russia and the Soviet Union

- Historical migration

- Josephine colonization

- Population transfer in the Soviet Union

- Polonization

- Expulsion of Germans after World War II

References

- Alan V. Murray (15 May 2017). The North-Eastern Frontiers of Medieval Europe: The Expansion of Latin Christendom in the Baltic Lands. Taylor & Francis. pp. 23–. ISBN 978-1-351-88483-9.

- Nora Berend (15 May 2017). The Expansion of Central Europe in the Middle Ages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 194–. ISBN 978-1-351-89008-3.

- CHRISTIAN LÜBKE. "Ostkolonisation, Ostsiedlung, Landesausbau im Mittelalter" (PDF). MGH-Archive. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- "Ostsiedlung – ein gesamteuropäisches Phänomen". GRIN Verlag. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Charles W. Ingrao; Franz A. J. Szabo (2008). The Germans and the East - p.9. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-55753-443-9.

- Paul Milliman (11 January 2013). ‘The Slippery Memory of Men’: The Place of Pomerania in the Medieval Kingdom of Poland - p.2. BRILL. ISBN 90-04-18274-8.

- Tadeusz Białecki, Historia Szczecina: zarys dziejów miasta od czasów najdawniejszych do 1980 r, Ossolineum, 1992

- Pomorze słowiańskie, Pomorze germańskie, Biuletyn Ministra Nauki i Szkolnictwa Wyższego

- Sébastien Rossignol (September 1, 2014). "Bilingualism in Medieval Europe". Cambridge University Press. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- Enno Bünz (2008). Ostsiedlung und Landesausbau in Sachsen: die Kührener Urkunde von 1154 und ihr historisches Umfeld. Leipziger Universitätsverlag. pp. 17–. ISBN 978-3-86583-165-1.

- Bartlett 1998, p. 14.

- Jenny Benham. "Treaty of Verdun (843)". Researchgate. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Schulman 2002, pp. 325–27.

- Wolfgang H. Fritze (1984). Der slawische Aufstand von 983: eine Schicksalswende in der Geschichte Mitteleuropas.

- "Terra Mariana". The Encyclopedia Americana. Americana Corp. 1967.

- Medieval Livonia @ google books

- referred to by historians as Medieval Livonia or Old LivoniaOld Livonia @ google books to distinguish it from the rump-Livonia (Duchy of Livonia) and the Governorate of Livonia that was formed from part of its territories after its breakup.

- Bilmanis, Alfreds (1944). Latvian-Russian relations: documents. The Latvian legation.

- Herbermann, Charles George (1907). The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company.

- Bilmanis, Alfreds (1945). The Church in Latvia. Drauga vēsts.

- Plakans, Andrejs. The Latvians: A Short History. Hoover Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-8179-9303-0.

- Skyum-Nielsen, Niels (1981). Danish Medieval History & Saxo Grammaticus. Museum Tusculanum Press. p. 129. ISBN 87-88073-30-0.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). "The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research". In Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell (eds.). The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak. Budapest. pp. 654–667, here p. 659. ISBN 963-9116-67-X.

- Paweł Zaremba, Historia Polski: od zarania Front Paweł Zaremba, page 163, 1961

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). "The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research". In Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell (eds.). The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak. Budapest. pp. 654–667, here p. 660. ISBN 963-9116-67-X.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). "The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research". In Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell (eds.). The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak. Budapest. pp. 654–667, here p. 658. ISBN 963-9116-67-X.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). "The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research". In Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell (eds.). The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak. Budapest. pp. 654–667, here p. 659–60. ISBN 963-9116-67-X.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (2007). "Medieval Colonization in Europe". In Charles W. Ingrao; Franz A. J. Szabo (eds.). The Germans and the East. Purdue University Press. pp. 27–37, here p. 29.

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 156, 159. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. p. 156. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Anna Paner, Jan Iluk: Historia Polski Virtual Library of Polish Literature, Katedra Kulturoznawstwa, Wydział Filologiczny, Uniwersytet Gdański..

- The German Hansa P. Dollinger, page 16, Routledge 1999

- Francis W. Carter, Trade and urban development in Poland: an economic geography of Cracow, from its origins to 1795, Cambridge University Press, 1994, pg. 381, quote: "Some German historians are inclined to regard Polish medieval towns as a result of municipal German colonization in the East, or even as East German towns. Towns, however, existed in Poland long before German colonists came, and the urban centres contained numerous nationalities as well as Poles."

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. de Gruyter. pp. 141f., 148, 154–155. ISBN 3-11-017061-2. Medieval Latin lacked a dedicated term for the Burgstadt settlements, contemporary documents refer to them as civitates, oppida or urbes Brachmann, Hansjürgen (1995). "Von der Burg zur Stadt. Die Frühstadt in Ostmitteleuropa". Archaeologia historica. 20: 315–321, 315. Schich (2007) rejected a proposal of Stoob (1986) to discontinue the use of compound words including "town" for these places, such as Protostadt (lit. "proto town"), Burgstadt, Frühstadt and Stoob's own, earlier proposal Grodstadt (lit. "grod town"). Stoob says that this would suggests, unjustified, a relation to the high medieval towns. Schich says that "if — despite the undisputable break in the 'urban' development in this area — terms like Burgstadt and Frühstadt are used here, then this is based on a broader ... understanding of the term 'town.' Frühstadt then denotes an early form of town-like settlements preceding the high medieval towns, without insinuating an evolution from Burgstadt or Frühstadt to the communal town." Schich, Winfried (2007). Schich, Winfried; Neumeister, Peter (eds.). Wirtschaft und Kulturlandschaft. BWV Verlag. p. 266. ISBN 3-8305-0378-4. Cf. also Benl, R, in Buchholz (1999): Pommern. Siedler, p. 75; also Rădvan, Laurențiu (2010). At Europe's Borders. Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. p. 5. ISBN 90-04-18010-9., quote: "This work will often make use of the phrase "pre-urban settlement." This type of early urban settlement was often the subject of scholarly debate, since the terminology at work was not entirely consistent. Some preferred the phrase we have adopted, while others relied on 'proto-towns,' 'embryonic-towns,' or 'incipient towns.'"

- Knefelkamp, Ulrich (2002). Das Mittelalter. Geschichte im Überblick. UTB Uni-Taschenbücher (in German). 2105 (2 ed.). UTB. p. 242. ISBN 3-8252-2105-9.

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. p. 155. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Piskorski, Jan Maria (1999). "The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research". In Nagy, Balázs; Sebők, Marcell (eds.). The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak. Budapest. pp. 654–667, here p. 661. ISBN 963-9116-67-X.

- Rădvan, Laurențiu (2010). At Europe's Borders. Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. pp. 31–32. ISBN 90-04-18010-9.

- Rădvan, Laurențiu (2010). At Europe's Borders. Medieval Towns in the Romanian Principalities. BRILL. p. 32. ISBN 90-04-18010-9.

- Enno Bünz: Die Rolle der Niederländer in der Ostsiedlung, in: Ostsiedlung und Landesausbau in Sachsen, 2008.

- K. Gündisch, Transylvania and the Transylvanian Saxons, Langen-Müller, München. ISBN 3784426859

- Klaus Herbers, Nikolas Jaspert, Grenzräume und Grenzüberschreitungen im Vergleich: Der Osten und der Westen des mittelalterlichen Lateineuropa, 2007, pp. 76ff, ISBN 3-05-004155-2, ISBN 978-3-05-004155-1

- Schich, Winfried; Neumeister, Peter (2007). Bibliothek der brandenburgischen und preussischen Geschichte. Volume 12. Wirtschaft und Kulturlandschaft: Gesammelte Beiträge 1977 bis 1999 zur Geschichte der Zisterzienser und der "Germania Slavica". BWV Verlag. pp. 217–218. ISBN 3-8305-0378-4. Retrieved 2009-08-25.

- Schwarz, Gabriele (1989). Lehrbuch der allgemeinen Geographie. Volume 6. Allgemeine Siedlungsgeographie I (4 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 189. ISBN 3-11-007895-3.

- Schwarz, Gabriele (1989). Lehrbuch der allgemeinen Geographie. Volume 6. Allgemeine Siedlungsgeographie I (4 ed.). Walter de Gruyter. p. 190. ISBN 3-11-007895-3.

- Horst Wernicke, Greifswald:Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.25, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- Horst Wernicke, Greifswald:Geschichte der Stadt, Helms, 2000, p.34, ISBN 3-931185-56-7

- Oskar Halecki, W: F. Reddaway, J. H. Penson, The Cambridge History of Poland, Cambridge University Press, 1971, pg. 125

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. p. 87. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

Das städtische Bürgertum war — auch in Polen und Böhmen, zunächst überwiegend deutscher Herkunft.

- Norman Davies, Roger Moorhouse (2002). Znak. ed. Mikrokosmos. Kraków. pp. :110. ISBN 83-240-0172-7.

- Kancelaria miasta Krakowa w średniowieczu Uniwersytet Jagielloński, 1995, page 15

- The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research, w: B. Nagy, M. Sebők (red.), The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak, Budapest 1999, s. 654-667

- Brather, Sebastian (2001). Archäologie der westlichen Slawen. Siedlung, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft im früh- und hochmittelalterlichen Ostmitteleuropa. Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde (in German). 30. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 156, 158. ISBN 3-11-017061-2.

- Jan Maria Piskorski: The Historiography of the So-called "East Colonisation" and the Current State of Research, in: B. Nagy, M. Sebők (red.), The Man of Many Devices, Who Wandered Full Many Ways... Festschrift in Honour of Janos Bak, Budapest 1999, pages 654–667

- Hartmut Boockmann, Ostpreussen und Westpreussen, Siedler 2002, p. 161,ISBN 3-88680-212-4

- Howard B. Clarke, Anngret Simms, The Comparative History of Urban Origins in Non-Roman Europe: Ireland, Wales, Denmark, Germany, Poland, and Russia from the Ninth to the Thirteenth Century B.A.R., p.690, 1985

- Weinhold, Karl (1887). Die Verbreitung und die Herkunft der Deutschen in Schlesien [The Spread and the Origin of Germans in Silesia] (in German). Stuttgart: J. Engelhorn.

- Werner Buchholz (1999). Pommern. Siedler. p. 17. ISBN 3-88680-272-8.

Die deutschen Siedlungsvorgänge in Pommern folgten ebensowenig wie die übrigen Wanderungsbewegungen einer wie auch immer gearteten Ideologie. Vielmehr war die deutsche Siedlung in Pommern ausschließlich von praktischen Erfordernissen geprägt. ... Erst die um die Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts sich durchsetzende nationale Geschichtsschreibung konstruierte rückblickend einen slawisch-germanischen Gegensatz in die deutsche Ostsiedlung des Hochmittelalters hinein. Aber das war die Ideologie des 19. Jahrhunderts, nicht des Mittelalters. ... Angesiedelt werden sollten "cuiuscunque gentis et cuiuscunque artis homines" (Menschen welcher Herkunft und welchen Handwerks auch immer), so steht es in zahlreichen von pommerschen Herzögen und rügischen Fürsten ausgestellten Urkunden.

Sources

- Bartlett, Robert (1998). Die Geburt Europas aus dem Geist der Gewalt. Eroberung, Kolonisation und kultureller Wandel von 950 bis 1350. Knaur München. ISBN 3-426-60639-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kleineberg, A; Marx Chr.; Knobloch E.; Lelgemann D.: Germania und die Insel Thule. Die Entschlüsselung von Ptolemaios' "Atlas der Oikumene". WBG 2010. ISBN 978-3-534-23757-9.

- Horst Gründer, Peter Johanek, Kolonialstädte, europäische Enklaven oder Schmelztiegel der Kulturen?: Europäische Enklaven oder Schmelztiegel der Kulturen?, 2001, ISBN 3-8258-3601-0, ISBN 978-3-8258-3601-6

- Paul Reuber, Anke Strüver, Günter Wolkersdorfer, Politische Geographien Europas — Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt: Annäherungen an ein umstrittenes Konstrukt, 2005, ISBN 3-8258-6523-1, ISBN 978-3-8258-6523-8

- Alain Demurger, Wolfgang Kaiser, Die Ritter des Herrn: Geschichte der Geistlichen Ritterorden, 2003, ISBN 3-406-50282-2, ISBN 978-3-406-50282-8

- Herrmann, Die Slawen in Deutschland

- Ulrich Knefelkamp, M. Stolpe, Zisterzienser: Norm, Kultur, Reform — 900 Jahre Zisterzienser, 2001, ISBN 3-540-64816-X, 9783540648161

- Werner Rösener, Agrarwirtschaft, Agrarverfassung und ländliche Gesellschaft im Mittelalter, 1988, ISBN 3-486-55024-1, ISBN 978-3-486-55024-5

- Schulman, Jana K. (2002). The Rise of the Medieval World, 500–1300: A Biographical Dictionary. Greenwood Press.

- Wilhelm von Sommerfeld, Geschichte der Germanisierung des Herzogtums Pommern oder Slavien bis zum Ablauf des 13. Jahrhunderts, Adamant Media Corporation, U.S.A. (unabridged facsimile of the edition published by Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1896), 2005, ISBN 1-4212-3832-2

Further reading

- Charles Higounet (1911–1988) Les allemands en Europe centrale et oriental au moyen age

- German translation: Die deutsche Ostsiedlung im Mittelalter

- Japanese translation: ドイツ植民と東欧世界の形成, 彩流社, by Naoki Miyajima

- Bielfeldt et al., Die Slawen in Deutschland. Ein Handbuch, Hg. Joachim Herrmann, Akademie-Verlag Berlin, 1985