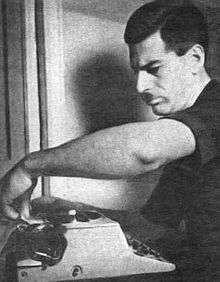

Elio Vittorini

Elio Vittorini (Italian pronunciation: [ˈɛːljo vittoˈriːni] (![]()

Elio Vittorini | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 23 July 1908 Syracuse, Sicily, Italy |

| Died | 12 February 1966 (aged 57) Milan, Italy |

| Occupation | Writer, novelist |

Life

Vittorini was born in Syracuse, Sicily, and throughout his childhood moved around Sicily with his father, a railroad worker. Several times he ran away from home, culminating in his leaving Sicily for good in 1924. For a brief period, he found employment as a construction worker in the Julian March, after which he moved to Florence to work as a type corrector (a line of work he abandoned in 1934 due to lead poisoning). Around 1927 his work began to be published in literary journals. In many cases, separate editions of his novels and short stories from this period, such as The Red Carnation were not published until after World War II, due to fascist censorship. In 1937, he was expelled from the National Fascist Party for writing in support of the Republican side in the Spanish Civil War.

In 1939 he moved, this time to Milan. An anthology of American literature which he edited was, once more, delayed by censorship. Remaining an outspoken critic of Benito Mussolini's regime, Vittorini was arrested and jailed in 1942. He joined the Italian Communist Party and began taking an active role in the Resistance, which provided the basis for his 1945 novel Men and not Men. Also in 1945, he briefly became the editor of the Italian Communist daily L'Unita and weekly Il Politecnico .[1]

After the war, Vittorini chiefly concentrated on his work as editor, helping publish work by young Italians such as Calvino and Fenoglio. His last major published work of fiction during his lifetime was 1956's Erica and her Sisters. The news of the events of the Hungarian Uprising deeply shook his convictions in Communism and made him decide to largely abandon writing, leaving unfinished work which was to be published in unedited form posthumously. For the remainder of his life, Vittorini continued in his post as an editor. In 1959, he co-founded with Calvino Il Menabò, a cultural journal devoted to literature in the modern industrial age. He also ran as a candidate on an Italian Socialist Party list. He died in Milan in 1966. He was an atheist.[2]

Partial bibliography

- Racconti di piccola borghesia (1931)

- Il garofano rosso (Translated as The Red Carnation, 1933)

- Conversazione in Sicilia (Translated as Conversations in Sicily, 1941)

- Uomini e no (Translated as Men and not Men, 1945)

- Le donne di Messina (1949) (Translated by Frances Frenaye, Women of Messina, 1973)

- Erica e suoi fratelli Translated as (Erica, 1956)

He also translated the works of Defoe, Poe, Steinbeck, Faulkner, Lawrence, Maugham and others into Italian.

Biography

- Un padre e un figlio. Biografia famigliare di Elio Vittorini / Demetrio Vittorini. Bellinzona [Switzerland]: Salvioni, 2000. (Demetrio Vittorini is Elio Vittorini's son.)

References

- Herbert Lottman (15 November 1998). The Left Bank: Writers, Artists, and Politics from the Popular Front to the Cold War. University of Chicago Press. p. 252. ISBN 978-0-226-49368-8. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Berti Arnoaldi, Francesco, L'amico cattolico, Edizioni Pendragon, 2005, p. 11