Manitoba

Manitoba (/ˌmænɪˈtoʊbə/ (![]()

Manitoba | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): | |

| Coordinates: 55°00′00″N 97°00′00″W | |

| Country | Canada |

| Confederation | 15 July 1870 (5th) |

| Capital | Winnipeg |

| Largest city | Winnipeg |

| Largest metro | Winnipeg Capital Region |

| Government | |

| • Lieutenant Governor | Janice Filmon |

| • Premier | Brian Pallister (Progressive Conservative) |

| Legislature | Legislative Assembly of Manitoba |

| Federal representation | Parliament of Canada |

| House seats | 14 of 338 (4.1%) |

| Senate seats | 6 of 105 (5.7%) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 649,950 km2 (250,950 sq mi) |

| • Land | 548,360 km2 (211,720 sq mi) |

| • Water | 101,593 km2 (39,225 sq mi) 15.6% |

| Area rank | Ranked 8th |

| 6.5% of Canada | |

| Population | |

| • Total | 1,278,365 [1] |

| • Estimate (2020 Q2) | 1,379,121 [2] |

| • Rank | Ranked 5th |

| • Density | 2.33/km2 (6.0/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Manitoban |

| Official languages | English[3] |

| GDP | |

| • Rank | 6th |

| • Total (2015) | C$65.862 billion[4] |

| • Per capita | C$50,820 (9th) |

| HDI | |

| • HDI (2018) | 0.897[5]—Very high (10th) |

| Time zone | Central: UTC–6 (DST −5) |

| Flower | Prairie crocus |

| Tree | White spruce |

| Bird | Great grey owl |

| Website | www |

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |

Indigenous peoples have inhabited what is now Manitoba for thousands of years. In the early 17th century, fur traders began arriving in the area and establishing settlements along the Nelson, Assiniboine, and Red rivers, and on the Hudson Bay shoreline. The Kingdom of England secured control of the region in 1673, and subsequently created a territory named Rupert's Land which was placed under the administration of the Hudson's Bay Company. Rupert's Land, which covered the entirety of present-day Manitoba, grew and evolved from 1673 until 1869 with significant settlements of Indigenous and Métis people in the Red River Colony. In 1869, negotiations with the Government of Canada for the creation of the province of Manitoba commenced. During the negotiations, several factors led to an armed uprising of the Métis people against the Government of Canada, a conflict known as the Red River Rebellion. The resolution of the rebellion and further negotiations led to Manitoba becoming the fifth province to join Canadian Confederation, when the Parliament of Canada passed the Manitoba Act on July 15, 1870.

Manitoba's capital and largest city, Winnipeg, is the eighth-largest census metropolitan area in Canada. Other census agglomerations in the province are Brandon, Steinbach, Thompson, Portage la Prairie, and Winkler.

Etymology

The name Manitoba is believed to be derived from the Cree, Ojibwe or Assiniboine languages. The name derives from Cree manitou-wapow or Ojibwe manidoobaa, both meaning "straits of Manitou, the Great Spirit", a place referring to what are now called The Narrows in the centre of Lake Manitoba. It may also be from the Assiniboine for "Lake of the Prairie",[6] which is rendered in the language as minnetoba.[7]

The lake was known to French explorers as Lac des Prairies. Thomas Spence chose the name to refer to a new republic he proposed for the area south of the lake. Métis leader Louis Riel also chose the name, and it was accepted in Ottawa under the Manitoba Act of 1870.[8]

Geography

Manitoba is bordered by the provinces of Ontario to the east and Saskatchewan to the west, the territory of Nunavut to the north, and the US states of North Dakota and Minnesota to the south. The province possibly meets the Northwest Territories at the four corners quadripoint to the extreme northwest, though surveys have not been completed and laws are unclear about the exact location of the Nunavut–NWT boundary. Manitoba adjoins Hudson Bay to the northeast, and is the only prairie province to have a saltwater coastline. The Port of Churchill is Canada's only Arctic deep-water port. Lake Winnipeg is the tenth-largest freshwater lake in the world. Hudson Bay is the world's second-largest bay by area. Manitoba is at the heart of the giant Hudson Bay watershed, once known as Rupert's Land. It was a vital area of the Hudson's Bay Company, with many rivers and lakes that provided excellent opportunities for the lucrative fur trade.

Hydrography and terrain

The province has a saltwater coastline bordering Hudson Bay and more than 110,000 lakes,[9] covering approximately 15.6 percent or 101,593 square kilometres (39,225 sq mi) of its surface area.[10] Manitoba's major lakes are Lake Manitoba, Lake Winnipegosis, and Lake Winnipeg, the tenth-largest freshwater lake in the world.[11] 29,000 square kilometres of traditional First Nations lands and boreal forest on Lake Winnipeg's east side were officially designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site known as Pimachiowin Aki in 2018.[12]

Manitoba is at the center of the Hudson Bay drainage basin, with a high volume of the water draining into Lake Winnipeg and then north down the Nelson River into Hudson Bay. This basin's rivers reach far west to the mountains, far south into the United States, and east into Ontario. Major watercourses include the Red, Assiniboine, Nelson, Winnipeg, Hayes, Whiteshell and Churchill rivers. Most of Manitoba's inhabited south has developed in the prehistoric bed of Glacial Lake Agassiz. This region, particularly the Red River Valley, is flat and fertile; receding glaciers left hilly and rocky areas throughout the province.[13]

Baldy Mountain is the province's highest point at 832 metres (2,730 ft) above sea level,[14] and the Hudson Bay coast is the lowest at sea level. Riding Mountain, the Pembina Hills, Sandilands Provincial Forest, and the Canadian Shield are also upland regions. Much of the province's sparsely inhabited north and east lie on the irregular granite Canadian Shield, including Whiteshell, Atikaki, and Nopiming Provincial Parks.[15]

Extensive agriculture is found only in the province's southern areas, although there is grain farming in the Carrot Valley Region (near The Pas). The most common agricultural activity is cattle husbandry (34.6%), followed by assorted grains (19.0%) and oilseed (7.9%).[16] Around 12 percent of Canada's farmland is in Manitoba.[17]

Climate

Manitoba has an extreme continental climate. Temperatures and precipitation generally decrease from south to north and increase from east to west.[18] Manitoba is far from the moderating influences of mountain ranges or large bodies of water. Because of the generally flat landscape, it is exposed to cold Arctic high-pressure air masses from the northwest during January and February. In the summer, air masses sometimes come out of the Southern United States, as warm humid air is drawn northward from the Gulf of Mexico.[19] Temperatures exceed 30 °C (86 °F) numerous times each summer, and the combination of heat and humidity can bring the humidex value to the mid-40s.[20] Carman, Manitoba recorded the second-highest humidex ever in Canada in 2007, with 53.0.[21] According to Environment Canada, Manitoba ranked first for clearest skies year round, and ranked second for clearest skies in the summer and for the sunniest province in the winter and spring.[22]

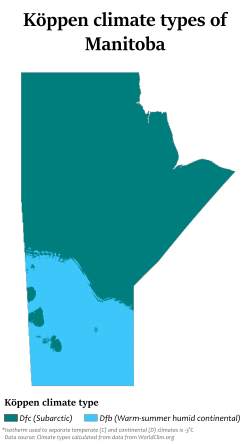

Southern Manitoba (including the city of Winnipeg), falls into the humid continental climate zone (Köppen Dfb). This area is cold and windy in the winter and often has blizzards because of the open landscape. Summers are warm with a moderate length. This region is the most humid area in the prairie provinces, with moderate precipitation. Southwestern Manitoba, though under the same climate classification as the rest of Southern Manitoba, is closer to the semi-arid interior of Palliser's Triangle. The area is drier and more prone to droughts than other parts of southern Manitoba.[23] This area is cold and windy in the winter and has frequent blizzards due to the openness of the Canadian Prairie landscape.[23] Summers are generally warm to hot, with low to moderate humidity.[23]

Southern parts of the province just north of Tornado Alley, experience tornadoes, with 16 confirmed touchdowns in 2016. In 2007, on 22 and 23 June, numerous tornadoes touched down, the largest an F5 tornado that devastated parts of Elie (the strongest recorded tornado in Canada).[24]

The province's northern sections (including the city of Thompson) fall in the subarctic climate zone (Köppen climate classification Dfc). This region features long and extremely cold winters and brief, warm summers with little precipitation.[25] Overnight temperatures as low as −40 °C (−40 °F) occur on several days each winter.[25]

| Community | Region | July daily maximum[26] |

January daily maximum[26] |

Annual precipitation[26] |

Plant hardiness zone[27] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morden | Pembina Valley | 26 °C (79 °F) | −10 °C (14 °F) | 541 mm (21 in) | 3A |

| Winnipeg | Winnipeg | 26 °C (79 °F) | −11 °C (12 °F) | 521 mm (21 in) | 2B |

| Pierson | Westman Region | 27 °C (81 °F) | −9 °C (16 °F) | 457 mm (18 in) | 2B |

| Dauphin | Parkland | 25 °C (77 °F) | −10 °C (14 °F) | 482 mm (19 in) | 2B |

| Steinbach | Eastman | 25 °C (77 °F) | −11 °C (12 °F) | 581 mm (23 in) | 2B |

| Portage la Prairie | Central Plains | 26 °C (79 °F) | −9 °C (16 °F) | 532 mm (21 in) | 3A |

| Brandon | Westman | 25 °C (77 °F) | −11 °C (12 °F) | 474 mm (19 in) | 2B |

| The Pas | Northern | 24 °C (75 °F) | −14 °C (7 °F) | 450 mm (18 in) | 2B |

| Thompson | Northern | 23 °C (73 °F) | −18 °C (0 °F) | 474 mm (19 in) | 2B |

| Churchill | Northern | 18 °C (64 °F) | −22 °C (−8 °F) | 453 mm (18 in) | 0A |

Flora and fauna

Manitoba natural communities may be grouped within five ecozones: boreal plains, prairie, taiga shield, boreal shield and Hudson plains. Three of these—taiga shield, boreal shield and Hudson plain—contain part of the Boreal forest of Canada which covers the province's eastern, southeastern, and northern reaches.[28]

Forests make up about 263,000 square kilometres (102,000 sq mi), or 48 percent, of the province's land area.[29] The forests consist of pines (Jack Pine, Red Pine, Eastern White Pine), spruces (White Spruce, Black Spruce), Balsam Fir, Tamarack (larch), poplars (Trembling Aspen, Balsam Poplar), birches (White Birch, Swamp Birch) and small pockets of Eastern White Cedar.[29]

Two sections of the province are not dominated by forest. The province's northeast corner bordering Hudson Bay is above the treeline and is considered tundra. The tallgrass prairie once dominated the south central and southeastern parts including the Red River Valley. Mixed grass prairie is found in the southwestern region. Agriculture has replaced much of the natural prairie but prairie still can be found in parks and protected areas; some are notable for the presence of the endangered western prairie fringed orchid,.[30][31]

Manitoba is especially noted for its northern polar bear population; Churchill is commonly referred to as the "Polar Bear Capital".[32] Other large animals, including moose, white-tailed deer, black bears, cougars, lynx, and wolves, are common throughout the province, especially in the provincial and national parks. There is a large population of red sided garter snakes near Narcisse; the dens there are home to the world's largest concentration of snakes.[33]

Manitoba's bird diversity is enhanced by its position on two major migration routes, with 392 confirmed identified species; 287 of these nesting within the province.[34] These include the great grey owl, the province's official bird, and the endangered peregrine falcon.[35]

Manitoba's lakes host 18 species of game fish, particularly species of trout, pike, and goldeye, as well as many smaller fish.[36]

History

First Nations Homeland and European settlement

Modern-day Manitoba was inhabited by the First Nations people shortly after the last ice age glaciers retreated in the southwest about 10,000 years ago; the first exposed land was the Turtle Mountain area.[37] The Ojibwe, Cree, Dene, Sioux, Mandan, and Assiniboine peoples founded settlements, and other tribes entered the area to trade. In Northern Manitoba, quartz was mined to make arrowheads. The first farming in Manitoba was along the Red River, where corn and other seed crops were planted before contact with Europeans.[38]

In 1611, Henry Hudson was one of the first Europeans to sail into what is now known as Hudson Bay, where he was abandoned by his crew.[39] The first European to reach present-day central and southern Manitoba was Sir Thomas Button, who travelled upstream along the Nelson River to Lake Winnipeg in 1612 in an unsuccessful attempt to find and rescue Hudson.[40] When the British ship Nonsuch sailed into Hudson Bay in 1668–1669, she became the first trading vessel to reach the area; that voyage led to the formation of the Hudson's Bay Company, to which the British government gave absolute control of the entire Hudson Bay watershed. This watershed was named Rupert's Land, after Prince Rupert, who helped to subsidize the Hudson's Bay Company.[41] York Factory was founded in 1684 after the original fort of the Hudson's Bay Company, Fort Nelson (built in 1682), was destroyed by rival French traders.[42]

Pierre Gaultier de Varennes, sieur de La Vérendrye, visited the Red River Valley in the 1730s to help open the area for French exploration and trade.[43] As French explorers entered the area, a Montreal-based company, the North West Company, began trading with the local Indigenous people. Both the North West Company and the Hudson's Bay Company built fur-trading forts; the two companies competed in southern Manitoba, occasionally resulting in violence, until they merged in 1821 (the Hudson's Bay Company Archives in Winnipeg preserve the history of this era).[41]

Great Britain secured the territory in 1763 after their victory over France in the North American theatre of the Seven Years' War, better known as the French and Indian War in North America; lasting from 1754 to 1763. The founding of the first agricultural community and settlements in 1812 by Lord Selkirk, north of the area which is now downtown Winnipeg, led to conflict between British colonists and the Métis.[44] Twenty colonists, including the governor, and one Métis were killed in the Battle of Seven Oaks in 1816.[45] Thomas Spence attempted to be President of the Republic of Manitobah in 1867, that he and his council named.

Confederation

Rupert's Land was ceded to Canada by the Hudson's Bay Company in 1869 and incorporated into the Northwest Territories; a lack of attention to Métis concerns caused Métis leader Louis Riel to establish a local provisional government which formed into the Convention of Forty and the subsequent elected Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia on 9 March 1870.[46][47] This assembly subsequently sent three delegates to Ottawa to negotiate with the Canadian government. This resulted in the Manitoba Act and that province's entry into the Canadian Confederation. Prime Minister John A. Macdonald introduced the Manitoba Act in the House of Commons of Canada, the bill was given Royal Assent and Manitoba was brought into Canada as a province in 1870.[48] Louis Riel was pursued by British army officer Garnet Wolseley because of the rebellion, and Riel fled into exile.[49] The Canadian government blocked the Métis' attempts to obtain land promised to them as part of Manitoba's entry into confederation. Facing racism from the new flood of white settlers from Ontario, large numbers of Métis moved to what would become Saskatchewan and Alberta.[48]

Numbered Treaties were signed in the late 19th century with the chiefs of First Nations that lived in the area. They made specific promises of land for every family. As a result, a reserve system was established under the jurisdiction of the Federal Government.[50] The prescribed amount of land promised to the native peoples was not always given; this led Indigenous groups to assert rights to the land through land claims, many of which are still ongoing.[51]

The original province of Manitoba was a square one-eighteenth of its current size, and was known colloquially as the "postage stamp province".[52] Its borders were expanded in 1881, taking land from the Northwest Territories and the District of Keewatin, but Ontario claimed a large portion of the land; the disputed portion was awarded to Ontario in 1889. Manitoba grew to its current size in 1912, absorbing land from the Northwest Territories to reach 60°N, uniform with the northern reach of its western neighbours Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia.[52]

The Manitoba Schools Question showed the deep divergence of cultural values in the territory. The Catholic Franco-Manitobans had been guaranteed a state-supported separate school system in the original constitution of Manitoba, but a grassroots political movement among English Protestants from 1888 to 1890 demanded the end of French schools. In 1890, the Manitoba legislature passed a law removing funding for French Catholic schools.[53] The French Catholic minority asked the federal government for support; however, the Orange Order and other anti-Catholic forces mobilized nationwide to oppose them.[54]

The federal Conservatives proposed remedial legislation to override Manitoba, but they were blocked by the Liberals, led by Wilfrid Laurier, who opposed the remedial legislation because of his belief in provincial rights.[53] Once elected Prime Minister in 1896, Laurier implemented a compromise stating Catholics in Manitoba could have their own religious instruction for 30 minutes at the end of the day if there were enough students to warrant it, implemented on a school-by-school basis.[53]

Contemporary era

By 1911, Winnipeg was the third largest city in Canada, and remained so until overtaken by Vancouver in the 1920s.[55] A boomtown, it grew quickly around the start of the 20th century, with outside investors and immigrants contributing to its success.[56] The drop in growth in the second half of the decade was a result of the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, which reduced reliance on transcontinental railways for trade, as well as a decrease in immigration due to the outbreak of the First World War.[57] Over 18,000 Manitoba residents enlisted in the first year of the war; by the end of the war, 14 Manitobans had received the Victoria Cross.[58]

During World War 1, Nellie McClung started the campaign for women's votes. On January 28, 1916, the vote for women was legalized. Manitoba was the first province to allow women to vote, obviously only in provincial elections. This was two years before Canada as a country granted women the right to vote.[59]

After the First World War ended, severe discontent among farmers (over wheat prices) and union members (over wage rates) resulted in an upsurge of radicalism, coupled with a polarization over the rise of Bolshevism in Russia.[60] The most dramatic result was the Winnipeg general strike of 1919. It began on 15 May and collapsed on 25 June 1919; as the workers gradually returned to their jobs, the Central Strike Committee decided to end the movement.[61]

Government efforts to violently crush the strike, including a Royal Northwest Mounted Police charge into a crowd of protesters that resulted in multiple casualties and one death, had led to the arrest of the movement's leaders.[61] In the aftermath, eight leaders went on trial, and most were convicted on charges of seditious conspiracy, illegal combinations, and seditious libel; four were aliens who were deported under the Canadian Immigration Act.[62]

The Great Depression (1929–c. 1939) hit especially hard in Western Canada, including Manitoba. The collapse of the world market combined with a steep drop in agricultural production due to drought led to economic diversification, moving away from a reliance on wheat production.[63] The Manitoba Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, forerunner to the New Democratic Party of Manitoba (NDP), was founded in 1932.[64]

Canada entered the Second World War in 1939. Winnipeg was one of the major commands for the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan to train fighter pilots, and there were air training schools throughout Manitoba. Several Manitoba-based regiments were deployed overseas, including Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. In an effort to raise money for the war effort, the Victory Loan campaign organized "If Day" in 1942. The event featured a simulated Nazi invasion and occupation of Manitoba, and eventually raised over C$65 million.[65]

Winnipeg was inundated during the 1950 Red River Flood and had to be partially evacuated. In that year, the Red River reached its highest level since 1861 and flooded most of the Red River Valley. The damage caused by the flood led then-Premier Duff Roblin to advocate for the construction of the Red River Floodway; it was completed in 1968 after six years of excavation. Permanent dikes were erected in eight towns south of Winnipeg, and clay dikes and diversion dams were built in the Winnipeg area. In 1997, the "Flood of the Century" caused over C$400 million in damages in Manitoba, but the floodway prevented Winnipeg from flooding.[66]

In 1990, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney attempted to pass the Meech Lake Accord, a series of constitutional amendments to persuade Quebec to endorse the Canada Act 1982. Unanimous support in the legislature was needed to bypass public consultation. Manitoba politician Elijah Harper, a Cree, opposed because he did not believe First Nations had been adequately involved in the Accord's process, and thus the Accord failed.[67]

In 2013, Manitoba was the second province to make accessibility legislation law, protecting the rights of persons with disabilities.[68]

Demography

| City | 2016 | 2011 |

|---|---|---|

| Winnipeg | 705,244 | 663,617 |

| Brandon | 48,859 | 46,061 |

| Steinbach | 15,829 | 13,524 |

| Portage la Prairie | 13,304 | 12,996 |

| Thompson | 13,678 | 12,829 |

| Winkler | 12,591 | 10,670 |

| Selkirk | 10,278 | 9,834 |

| Morden | 8,668 | 7,812 |

| Dauphin | 8,457 | 8,251 |

| Table source: Statistics Canada | ||

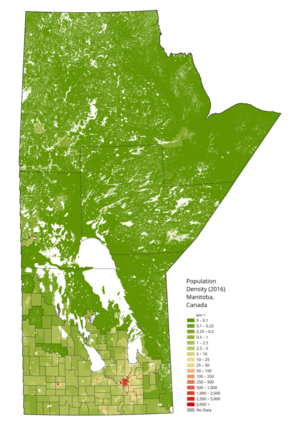

At the 2011 census, Manitoba had a population of 1,208,268, more than half of which is in the Winnipeg Capital Region; Winnipeg is Canada's eighth-largest Census Metropolitan Area, with a population of 730,018 (2011 Census[69]). Although initial colonization of the province revolved mostly around homesteading, the last century has seen a shift towards urbanization; Manitoba is the only Canadian province with over fifty-five percent of its population in a single city.[70]

According to the 2006 Canadian census,[69] the largest ethnic group in Manitoba is English (22.9%), followed by German (19.1%), Scottish (18.5%), Ukrainian (14.7%), Irish (13.4%), North American Indian (10.6%), Polish (7.3%), Métis (6.4%), French (5.6%), Dutch (4.9%), Russian (4.0%), and Icelandic (2.4%). Almost one-fifth of respondents also identified their ethnicity as "Canadian".[71] Indigenous peoples (including Métis) are Manitoba's fastest-growing ethnic group, representing 13.6 percent of Manitoba's population as of 2001 (some reserves refused to allow census-takers to enumerate their populations or were otherwise incompletely counted).[72][73] There is a significant Franco-Manitoban minority (148,370). Gimli, Manitoba is home to the largest Icelandic community outside of Iceland.[74]

Religion

Most Manitobans belong to a Christian denomination: on the 2001 census, 758,760 Manitobans (68.7%) reported being Christian, followed by 13,040 (1.2%) Jewish, 5,745 (0.5%) Buddhist, 5,485 (0.5%) Sikh, 5,095 (0.5%) Muslim, 3,840 (0.3%) Hindu, 3,415 (0.3%) Indigenous spirituality and 995 (0.1%) pagan.[75] 201,825 Manitobans (18.3%) reported no religious affiliation.[75] The largest Christian denominations by number of adherents were the Roman Catholic Church with 292,970 (27%); the United Church of Canada with 176,820 (16%); and the Anglican Church of Canada with 85,890 (8%).[75]

Economy

Manitoba has a moderately strong economy based largely on natural resources. Its Gross Domestic Product was C$50.834 billion in 2008.[76] The province's economy grew 2.4 percent in 2008, the third consecutive year of growth.[77] The average individual income in Manitoba in 2006 was C$25,100 (compared to a national average of C$26,500), ranking fifth-highest among the provinces.[78] As of October 2009, Manitoba's unemployment rate was 5.8 percent.[79]

Manitoba's economy relies heavily on agriculture, tourism, electricity, oil, mining, and forestry. Agriculture is vital and is found mostly in the southern half of the province, although grain farming occurs as far north as The Pas. Around 12 percent of Canadian farmland is in Manitoba.[17] The most common type of farm found in rural areas is cattle farming (34.6%),[16] followed by assorted grains (19.0%) and oilseed (7.9%).[16]

Manitoba is the nation's largest producer of sunflower seed and dry beans,[80] and one of the leading sources of potatoes. Portage la Prairie is a major potato processing centre, and is home to the McCain Foods and Simplot plants, which provide French fries for McDonald's, Wendy's, and other commercial restaurant chains.[81] Richardson International, one of the largest oat mills in the world, also has a plant in the municipality.[82]

Manitoba's largest employers are government and government-funded institutions, including crown corporations and services like hospitals and universities. Major private-sector employers are The Great-West Life Assurance Company, Cargill Ltd., and James Richardson and Sons Ltd.[83] Manitoba also has large manufacturing and tourism sectors. Churchill's Arctic wildlife is a major tourist attraction; the town is a world capital for polar bear and beluga whale watchers.[84] Manitoba is the only province with an Arctic deep-water seaport, at Churchill.[85]

In January 2018, the Canadian Federation of Independent Business claimed Manitoba was the most improved province for tackling red tape.[86]

Economic history

Manitoba's early economy depended on mobility and living off the land. Indigenous Nations (Cree, Ojibwa, Dene, Sioux and Assiniboine) followed herds of bison and congregated to trade among themselves at key meeting places throughout the province. After the arrival of the first European traders in the 17th century, the economy centred on the trade of beaver pelts and other furs.[87] Diversification of the economy came when Lord Selkirk brought the first agricultural settlers in 1811,[88] though the triumph of the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC) over its competitors ensured the primacy of the fur trade over widespread agricultural colonization.[87]

HBC control of Rupert's Land ended in 1868; when Manitoba became a province in 1870, all land became the property of the federal government, with homesteads granted to settlers for farming.[87] Transcontinental railways were constructed to simplify trade. Manitoba's economy depended mainly on farming, which persisted until drought and the Great Depression led to further diversification.[63]

Military bases

CFB Winnipeg is a Canadian Forces Base at the Winnipeg International Airport. The base is home to flight operations support divisions and several training schools, as well as the 1 Canadian Air Division and Canadian NORAD Region Headquarters.[89] 17 Wing of the Canadian Forces is based at CFB Winnipeg; the Wing has three squadrons and six schools.[90] It supports 113 units from Thunder Bay to the Saskatchewan/Alberta border, and from the 49th parallel north to the high Arctic. 17 Wing acts as a deployed operating base for CF-18 Hornet fighter–bombers assigned to the Canadian NORAD Region.[90]

The two 17 Wing squadrons based in the city are: the 402 ("City of Winnipeg" Squadron), which flies the Canadian designed and produced de Havilland Canada CT-142 Dash 8 navigation trainer in support of the 1 Canadian Forces Flight Training School's Air Combat Systems Officer and Airborne Electronic Sensor Operator training programs (which trains all Canadian Air Combat Systems Officer);[91] and the 435 ("Chinthe" Transport and Rescue Squadron), which flies the Lockheed C-130 Hercules tanker/transport in airlift search and rescue roles, and is the only Air Force squadron equipped and trained to conduct air-to-air refuelling of fighter aircraft.[90]

Canadian Forces Base Shilo (CFB Shilo) is an Operations and Training base of the Canadian Forces 35 kilometres (22 mi) east of Brandon. During the 1990s, Canadian Forces Base Shilo was designated as an Area Support Unit, acting as a local base of operations for Southwest Manitoba in times of military and civil emergency.[92] CFB Shilo is the home of the 1st Regiment, Royal Canadian Horse Artillery, both battalions of the 1 Canadian Mechanized Brigade Group, and the Royal Canadian Artillery. The Second Battalion of Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), which was originally stationed in Winnipeg (first at Fort Osborne, then in Kapyong Barracks), has operated out of CFB Shilo since 2004. CFB Shilo hosts a training unit, 3rd Canadian Division Training Centre. It serves as a base for support units of 3rd Canadian Division, also including 3 CDSG Signals Squadron, Shared Services Unit (West), 11 CF Health Services Centre, 1 Dental Unit, 1 Military Police Regiment, and an Integrated Personnel Support Centre. The base houses 1,700 soldiers.[92]

Government and politics

After the control of Rupert's Land was passed from Great Britain to the Government of Canada in 1869, Manitoba attained full-fledged rights and responsibilities of self-government as the first Canadian province carved out of the Northwest Territories.[93] The Legislative Assembly of Manitoba was established on 14 July 1870. Political parties first emerged between 1878 and 1883, with a two-party system (Liberals and Conservatives).[94] The United Farmers of Manitoba appeared in 1922, and later merged with the Liberals in 1932.[94] Other parties, including the Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), appeared during the Great Depression; in the 1950s, Manitoban politics became a three-party system, and the Liberals gradually declined in power.[94] The CCF became the New Democratic Party of Manitoba (NDP), which came to power in 1969.[94] Since then, the Progressive Conservatives and the NDP have been the dominant parties.[94]

Like all Canadian provinces, Manitoba is governed by a unicameral legislative assembly.[95] The executive branch is formed by the governing party; the party leader is the premier of Manitoba, the head of the executive branch. The head of state, Queen Elizabeth II, is represented by the Lieutenant Governor of Manitoba, who is appointed by the Governor General of Canada on advice of the Prime Minister.[96] The head of state is primarily a ceremonial role, although the Lieutenant Governor has the official responsibility of ensuring Manitoba has a duly constituted government.[96]

The Legislative Assembly consists of the 57 Members elected to represent the people of Manitoba.[97] The premier of Manitoba is Brian Pallister of the PC Party. The PCs were elected with a majority government of 40 seats.[98][99] The NDP holds 14 seats, and the Liberal Party have three seats but does not have official party status in the Manitoba Legislature.[99][100] The last provincial general election was held on 19 April 2016.[98] The province is represented in federal politics by 14 Members of Parliament and six Senators.[101][102]

Manitoba's judiciary consists of the Court of Appeal, the Court of Queen's Bench, and the Provincial Court. The Provincial Court is primarily for criminal law; 95 per cent of criminal cases in Manitoba are heard here.[103] The Court of Queen's Bench is the highest trial court in the province. It has four jurisdictions: family law (child and family services cases), civil law, criminal law (for indictable offences), and appeals. The Court of Appeal hears appeals from both benches; its decisions can only be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.[104]

Official languages

Both English and French are official languages of the legislature and courts of Manitoba, according to §23 of the Manitoba Act of 1870 (part of the Constitution of Canada). In April 1890, the Manitoba legislature attempted to abolish the official status of French and ceased to publish bilingual legislation. However, in 1985 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in the Reference re Manitoba Language Rights that §23 still applied, and that legislation published only in English was invalid (unilingual legislation was declared valid for a temporary period to allow time for translation).[105]

Although French is an official language for the purposes of the legislature, legislation, and the courts, the Manitoba Act does not require it to be an official language for the purpose of the executive branch (except when performing legislative or judicial functions).[106] Hence, Manitoba's government is not completely bilingual. The Manitoba French Language Services Policy of 1999 is intended to provide a comparable level of provincial government services in both official languages.[107] According to the 2006 Census, 82.8 percent of Manitoba's population spoke only English, 3.2 percent spoke only French, 15.1 percent spoke both, and 0.9 percent spoke neither.[108]

In 2010, the provincial government of Manitoba passed the Aboriginal Languages Recognition Act, which gives official recognition to seven indigenous languages: Cree, Dakota, Dene, Inuktitut, Michif, Ojibway and Oji-Cree.[109]

Transportation

Transportation and warehousing contribute approximately C$2.2 billion to Manitoba's GDP. Total employment in the industry is estimated at 34,500, or around 5 percent of Manitoba's population.[110] Trucks haul 95 percent of land freight in Manitoba, and trucking companies account for 80 percent of Manitoba's merchandise trade to the United States.[111] Five of Canada's twenty-five largest employers in for-hire trucking are headquartered in Manitoba.[111] C$1.18 billion of Manitoba's GDP comes directly or indirectly from trucking.[111]

Greyhound Canada and Grey Goose Bus Lines offer domestic bus service from the Winnipeg Bus Terminal. The terminal was relocated from downtown Winnipeg to the airport in 2009, and is a Greyhound hub.[112] Municipalities also operate localized transit bus systems.

Manitoba has two Class I railways: Canadian National Railway (CN) and Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR). Winnipeg is centrally located on the main lines of both carriers, and both maintain large inter-modal terminals in the city. CN and CPR operate a combined 2,439 kilometres (1,516 mi) of track in Manitoba.[111] Via Rail offers transcontinental and Northern Manitoba passenger service from Winnipeg's Union Station. Numerous small regional and short-line railways also run trains within Manitoba: the Hudson Bay Railway, the Southern Manitoba Railway, Burlington Northern Santa Fe Manitoba, Greater Winnipeg Water District Railway, and Central Manitoba Railway. Together, these smaller lines operate approximately 1,775 kilometres (1,103 mi) of track in the province.[111]

Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson International Airport, Manitoba's largest airport, is one of only a few 24-hour unrestricted airports in Canada and is part of the National Airports System.[113] A new, larger terminal opened in October 2011.[114] The airport handles approximately 195,000 tonnes (430,000,000 lb) of cargo annually, making it the third largest cargo airport in the country.[113]

Eleven regional passenger airlines and nine smaller and charter carriers operate out of the airport, as well as eleven air cargo carriers and seven freight forwarders.[111] Winnipeg is a major sorting facility for both FedEx and Purolator, and receives daily trans-border service from UPS.[111] Air Canada Cargo and Cargojet Airways use the airport as a major hub for national traffic.[111]

The Port of Churchill, owned by Arctic Gateway Group, is the only Arctic deep-water port in Canada. It is nautically closer to ports in Northern Europe and Russia than any other port in Canada.[85] It has four deep-sea berths for the loading and unloading of grain, general cargo and tanker vessels.[111] The port is served by the Hudson Bay Railway (also owned by Arctic Gateway Group). Grain represented 90 percent of the port's traffic in the 2004 shipping season.[111] In that year, over 600,000 tonnes (1.3×109 lb) of agricultural products were shipped through the port.[111]

Education

The first school in Manitoba was founded in 1818 by Roman Catholic missionaries in present-day Winnipeg; the first Protestant school was established in 1820.[115] A provincial board of education was established in 1871; it was responsible for public schools and curriculum, and represented both Catholics and Protestants. The Manitoba Schools Question led to funding for French Catholic schools largely being withdrawn in favour of the English Protestant majority.[116] Legislation making education compulsory for children between seven and fourteen was first enacted in 1916, and the leaving age was raised to sixteen in 1962.[117]

Public schools in Manitoba fall under the regulation of one of thirty-seven school divisions within the provincial education system (except for the Manitoba Band Operated Schools, which are administered by the federal government).[118] Public schools follow a provincially mandated curriculum in either French or English. There are sixty-five funded independent schools in Manitoba, including three boarding schools.[119] These schools must follow the Manitoban curriculum and meet other provincial requirements. There are forty-four non-funded independent schools, which are not required to meet those standards.[120]

There are five universities in Manitoba, regulated by the Ministry of Advanced Education and Literacy.[121] Four of these universities are in Winnipeg: the University of Manitoba, the largest and most comprehensive; the University of Winnipeg, a liberal arts school primarily focused on undergrad studies downtown; Université de Saint-Boniface, the province's only French-language university; and the Canadian Mennonite University, a religious-based institution. The Université de Saint-Boniface, established in 1818 and now affiliated with the University of Manitoba, is the oldest university in Western Canada. Brandon University, formed in 1899 and in Brandon, is the province's only university not in Winnipeg.[122]

Manitoba has thirty-eight public libraries; of these, twelve have French-language collections and eight have significant collections in other languages.[123] Twenty-one of these are part of the Winnipeg Public Library system. The first lending library in Manitoba was founded in 1848.[124]

Culture

Arts

The Minister of Culture, Heritage, Tourism and Sport is responsible for promoting and, to some extent, financing Manitoban culture.[125] Manitoba is the birthplace of the Red River Jig, a combination of Indigenous pow-wows and European reels popular among early settlers.[126] Manitoba's traditional music has strong roots in Métis and First Nations culture, in particular the old-time fiddling of the Métis.[127] Manitoba's cultural scene also incorporates classical European traditions. The Winnipeg-based Royal Winnipeg Ballet (RWB), is Canada's oldest ballet and North America's longest continuously operating ballet company; it was granted its royal title in 1953 under Queen Elizabeth II.[128] The Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra (WSO) performs classical music and new compositions at the Centennial Concert Hall.[129] Manitoba Opera, founded in 1969, also performs out of the Centennial Concert Hall.

Le Cercle Molière (founded 1925) is the oldest French-language theatre in Canada,[130] and Royal Manitoba Theatre Centre (founded 1958) is Canada's oldest English-language regional theatre.[131] Manitoba Theatre for Young People was the first English-language theatre to win the Canadian Institute of the Arts for Young Audiences Award, and offers plays for children and teenagers as well as a theatre school.[132] The Winnipeg Art Gallery (WAG), Manitoba's largest art gallery and the sixth largest in the country, hosts an art school for children; the WAG's permanent collection comprises over twenty thousand works, with a particular emphasis on Manitoban and Canadian art.[133][134]

The 1960s pop group The Guess Who was formed in Manitoba, and later became the first Canadian band to have a No. 1 hit in the United States;[135] Guess Who guitarist Randy Bachman later created Bachman–Turner Overdrive (BTO) with fellow Winnipeg-based musician Fred Turner.[136] Fellow rocker Neil Young, grew up in Manitoba, and later played in Buffalo Springfield, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young.[137] Folk rock band Crash Test Dummies formed in the late 1980s in Winnipeg and were the 1992 Juno Awards Group of the Year.[138]

Several prominent Canadian films were produced in Manitoba, such as The Stone Angel, based on the Margaret Laurence book of the same title, The Saddest Music in the World, Foodland, For Angela, and My Winnipeg. Major films shot in Manitoba include The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Capote,[139] both of which received Academy Award nominations.[140] Falcon Beach, an internationally broadcast television drama, was filmed at Winnipeg Beach, Manitoba.[141]

Manitoba has a strong literary tradition. Manitoban writer Bertram Brooker won the first-ever Governor General's Award for Fiction in 1936.[142] Cartoonist Lynn Johnston, author of the comic strip For Better or For Worse, was a finalist for a 1994 Pulitzer Prize and inducted into the Canadian Cartoonist Hall of Fame.[143] Margaret Laurence's The Stone Angel and A Jest of God were set in Manawaka, a fictional town representing Neepawa; the latter title won the Governor General's Award in 1966.[144] Carol Shields won both the Governor General's Award and the Pulitzer Prize for The Stone Diaries.[145] Gabrielle Roy, a Franco-Manitoban writer, won the Governor General's Award three times.[142] A quote from her writings is featured on the Canadian $20 bill.[146] Joan Thomas was nominated for the Governor General's Award twice and won in 2019 for Five Wives. The province has also been home to many of the key figures in Mennonite literature, including Governor General Award winning Miriam Toews, Giller winner David Bergen, Armin Wiebe and many others.[147]

Festivals

Festivals take place throughout the province, with the largest centred in Winnipeg. The inaugural Winnipeg Folk Festival was held in 1974 as a one-time celebration to mark Winnipeg's 100th anniversary. Today, the five-day festival is one of the largest folk festivals in North America with over 70 acts from around the world and an annual attendance of over 80,000. The Winnipeg Folk Festival's home – Birds Hill Provincial Park – is 34 kilometres outside of Winnipeg and for the five days of the festival, it becomes Manitoba's third largest "city." The Festival du Voyageur is an annual ten-day event held in Winnipeg's French Quarter, and is Western Canada's largest winter festival.[148] It celebrates Canada's fur-trading past and French-Canadian heritage and culture. Folklorama, a multicultural festival run by the Folk Arts Council, receives around 400,000 pavilion visits each year, of which about thirty percent are from non-Winnipeg residents.[148][149] The Winnipeg Fringe Theatre Festival is an annual alternative theatre festival, the second-largest festival of its kind in North America (after the Edmonton International Fringe Festival).[150]

Museums

Manitoban museums document different aspects of the province's heritage. The Manitoba Museum is the largest museum in Manitoba and focuses on Manitoban history from prehistory to the 1920s.[151] The full-size replica of the Nonsuch is the museum's showcase piece.[152] The Manitoba Children's Museum at The Forks presents exhibits for children.[153] There are two museums dedicated to the native flora and fauna of Manitoba: the Living Prairie Museum, a tall grass prairie preserve featuring 160 species of grasses and wildflowers, and FortWhyte Alive, a park encompassing prairie, lake, forest and wetland habitats, home to a large herd of bison.[154] The Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre houses the largest collection of marine reptile fossils in Canada.[155] Other museums feature the history of aviation, marine transport, and railways in the area. The Canadian Museum for Human Rights is the first Canadian national museum outside of the National Capital Region.[156]

Media

Winnipeg has two daily newspapers: the Winnipeg Free Press, a broadsheet with the highest circulation numbers in Manitoba, as well as the Winnipeg Sun, a smaller tabloid-style paper. There are several ethnic weekly newspapers,[157] including the weekly French-language La Liberté, and regional and national magazines based in the city. Brandon has two newspapers: the daily Brandon Sun and the weekly Wheat City Journal.[158] Many small towns have local newspapers.[159]

There are five English-language television stations and one French-language station based in Winnipeg. The Global Television Network (owned by Canwest) is headquartered in the city.[160] Winnipeg is home to twenty-one AM and FM radio stations, two of which are French-language stations.[161] Brandon's five local radio stations are provided by Astral Media and Westman Communications Group.[161] In addition to the Brandon and Winnipeg stations, radio service is provided in rural areas and smaller towns by Golden West Broadcasting, Corus Entertainment, and local broadcasters. CBC Radio broadcasts local and national programming throughout the province.[162] Native Communications is devoted to indigenous programming and broadcasts to many of the isolated native communities as well as to larger cities.[163]

Sports

Manitoba has five professional sports teams: the Winnipeg Blue Bombers (Canadian Football League), the Winnipeg Jets (National Hockey League), the Manitoba Moose (American Hockey League), the Winnipeg Goldeyes (American Association), and Valour FC (Canadian Premier League). The province was previously home to another team called the Winnipeg Jets, which played in the World Hockey Association and National Hockey League from 1972 until 1996, when financial troubles prompted a sale and move of the team, renamed the Phoenix Coyotes.[164] A second incarnation of the Winnipeg Jets returned, after True North Sports & Entertainment bought the Atlanta Thrashers and moved the team to Winnipeg in time for the 2011 hockey season.[165] Manitoba has two major junior-level hockey teams, the Western Hockey League's Brandon Wheat Kings and Winnipeg Ice, and one junior football team, the Winnipeg Rifles of the Canadian Junior Football League.

The province is represented in university athletics by the University of Manitoba Bisons, the University of Winnipeg Wesmen, and the Brandon University Bobcats. All three teams compete in the Canada West Universities Athletic Association, a regional division of U Sports.[166]

Curling is an important winter sport in the province with Manitoba producing more men's national champions than any other province, while additionally in the top 3 women's national champions, as well as multiple world champions in the sport. The province also hosts the world's largest curling tournament in the MCA Bonspiel.[167] The province is regular host to Grand Slam events which feature as the largest cash events in the sport such as the annual Manitoba Lotteries Women's Curling Classic as well as other rotating events.

Though not as prominent as hockey and curling, long track speed skating also features as a notable and top winter sport in Manitoba. The province has produced some of the world's best female speed skaters including Susan Auch and the country's top Olympic medal earners Cindy Klassen and Clara Hughes.[168]

See also

References

- "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2016 and 2011 censuses". Statistics Canada. 2 February 2017. Archived from the original on 4 May 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2017.

- "Estimates of population, Canada, provinces and territories". Statistics Canada. 28 September 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 29 September 2018.

- "The legal context of Canada's official languages". University of Ottawa. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2019.

- Statistics Canada. Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory (2015); 9 November 2016 [archived 19 September 2012; Retrieved 26 January 2017].

- "Sub-national HDI - Subnational HDI - Global Data Lab". globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Natural Resources Canada. Manitoba [archived 4 June 2008; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Strange Empire, a Narrative of the Northwest. Minnesota Historical Society Press; 1994. ISBN 978-0873512985. p. 192.

- Province of Manitoba. The Origin of the Name Manitoba [archived 19 March 2013; Retrieved 20 October 2013].

- Statistics Canada. Land and Freshwater area, by province and territory [archived 24 May 2011; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Travel Manitoba. Geography of Manitoba [archived 29 November 2010; Retrieved 10 February 2010].

- Lake Winnipeg Stewardship Board. Lake Winnipeg Facts [archived 14 June 2004; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Schwartz, Bryan; Cheung, Perry. East vs. West: Evaluating Manitoba Hydro's Options for a Hydro-Transmission Line from an International Law Perspective. Asper Review of International Business and Trade Law. 2007;7(4):4.

- Savage, Candace. Prairie: A Natural History. 2nd ed. Greystone Books; 2011. ISBN 978-1-55365-588-6. p. 52–53.

- Manitoba Parks Branch. Outdoor recreation master plan: Duck Mountain Provincial Park. Winnipeg: Manitoba Department of Tourism, Recreation and Cultural Affairs; 1973.

- Butler, George E. The Lakes and Lake Fisheries of Manitoba. Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 1950;79:24. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1949)79[18:tlalfo]2.0.co;2.

- Statistics Canada. Summary Table of Wheats and Grains by Province [archived 15 January 2011; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Statistics Canada. Total farm area, land tenure and land in crops, by province (Census of Agriculture, 1986 to 2006) (Manitoba) [archived 15 January 2011; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Ritchie, JC. Post-Glacial Vegetation of Canada. Cambridge University Press; 2004. ISBN 978-0-521-54409-2. p. 25.

- Vickers, Glenn; Buzza, Sandra; Schmidt, Dave; Mullock, John. The Weather of the Canadian Prairies. Navigation Canada; 2001 [Retrieved 11 February 2010]. p. 48, 51, 53–64.

- Environment Canada. Mean Max Temp History at The Forks, Manitoba [archived 28 October 2011; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Environment Canada. Canada's Top Ten Weather Stories for 2007 [archived 11 June 2011; Retrieved 8 November 2010].

- Environment Canada. Manitoba Weather Honours [archived 11 December 2008; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Ritter, Michael E. Midlatitude Steppe Climate; 2006 [archived 22 August 2007; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Environment Canada. Elie Tornado Upgraded to Highest Level on Damage Scale Canada's First Official F5 Tornado; 18 September 2007 [archived 11 June 2011; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Ritter, Michael E. Subarctic Climate; 2006 [archived 25 May 2008; Retrieved 7 August 2007].

- Environment Canada. [archived 27 February 2014; Retrieved 26 February 2014].

- Theweathernetwork.com. Lawn and Garden: Winnipeg, MB [archived 6 March 2014; Retrieved 26 February 2014].

- Oswald, Edward T.; Nokes, Frank H.. Field Guide to the Native Trees of Manitoba. Manitoba Conservation; 2016.

- Manitoba Conservation. Manitoba Forest Facts [archived 26 February 2009; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Fringed-orchid, Western Prairie [archived 6 July 2011; Retrieved 7 November 2009].

- Goedeke, T; Sharma, J; Delphey, P; Marshall Mattson, K (2008). "Platanthera praeclara". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2008: e.T132834A3464336. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2008.RLTS.T132834A3464336.en. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2018.

- Stirling, Ian; Guravich, Dan. Polar Bears. University of Michigan Press; 1998. ISBN 978-0-472-08108-0. p. 208.

- LeMaster, MP; Mason, RT. Annual and seasonal variation in the female sexual attractiveness pheromone of the red-sided garter snake, Thamnophis sirtalis parietalis. In: Marchlewska-Koj, Anna; Lepri, John J; Müller-Schwarze, Dietland. Chemical signals in vertebrates. Vol. 9. Springer; 2001. ISBN 978-0-306-46682-3. p. 370.

- Manitoba Avian Research Committee. Nature Manitoba. Checklist of the Birds of Manitoba [archived 21 April 2016; Retrieved 26 July 2016].

- Bezener, Andy; De Smet, Ken D. Manitoba birds. Lone Pine; 2000. ISBN 978-1-55105-255-7. p. 1–10.

- Manitoba Fisheries. Angler's Guide 2009; 2009 [archived 20 July 2011; Retrieved 22 February 2010]; p. 5.

- Ritchie, James AM; Brown, Frank; Brien, David. The Cultural Transmission of the Spirit of Turtle Mountain: A Centre for Peace and Trade for 10,000 Years. General Assembly and International Scientific Symposium. 2008;16:4–6.

- Flynn, Catherine; Syms, E Leigh. Manitoba's First Farmers. Manitoba History. Spring 1996;(31).

- Neatby, LH. Henry Hudson. In: Cook, Ramsay. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. online ed. Vol. 1. University of Toronto/Université Laval; 2013. p. 374–379.

- Eames, Aled. Sir Thomas Button. In: Cook, Ramsay. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. online ed. Vol. 1. University of Toronto/Université Laval; 1979. p. 144–145.

- Simmons, Deidre. Keepers of the Record: The History of the Hudson's Bay Company Archives. McGill-Queen's University Press; 2009. ISBN 978-0-7735-3620-3. p. 19–23, 83–85, 115.

- Stewart, Lillian. York Factory National Historic Site. Manitoba History. Spring 1988;(15).

- Zoltvany, Yves F. Pierre Gaultier De Varennes et De La Vérendrye. In: Cook, Ramsay. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. online ed. Vol. 3. University of Toronto/Université Lava; 2015. p. 246–254.

- Gray, John Morgan. Thomas Douglas. In: Cook, Ramsay. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. online ed. Vol. 5. University of Toronto/Université Laval; 2015. p. 264–269.

- Martin, Joseph E. The 150th Anniversary of Seven Oaks. MHS Transactions. 1965;3(22).

- "Indigenous and Northern Relations". Province of Manitoba.

- Lawrence, Barkwell. "A History of the Legislative Assembly of Assiniboia/le Conseil du Governement Provisoire" (PDF). www.legislativeassemblyofassiniboia.ca. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 October 2018.

- Sprague, DN. Canada and the Métis, 1869–1885. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 1988. ISBN 978-0-88920-964-0. p. 33–67, 89–129.

- Cooke, OA. Garnet Joseph Wolseley. In: Cook, Ramsay. Dictionary of Canadian Biography. online ed. Vol. 14. University of Toronto/Université Laval; 2015.

- Tough, Frank. As Their Natural Resources Fail: Native People and the Economic History of Northern Manitoba, 1870–1930. UBC Press; 1997. ISBN 978-0-7748-0571-1. p. 75–79.

- Government of Manitoba. First Nations Land Claims [archived 30 October 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Kemp, Douglas. From Postage Stamp to Keystone. Manitoba Pageant. April 1956.

- Fletcher, Robert. The Language Problem in Manitoba's Schools. MHS Transactions. 1949;3(6).

- McLauchlin, Kenneth. 'Riding The Protestant Horse': The Manitoba Schools Question and Canadian Politics, 1890–1896. Historical Studies. 1986;53:39–52.

- Hayes, Derek. Historical Atlas of Canada. D&M Adult; 2006. ISBN 978-1-55365-077-5. p. 227.

- CBC. Winnipeg Boomtown [archived 4 November 2011; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Silicz, Michael. The heart of the continent?. The Manitoba. 10 September 2008. University of Manitoba.

- Morton, William L. Manitoba, a History. University of Toronto Press; 1957. p. 345–359.

- Status of Women Canada. 100th Anniversary of Women's First Right to Vote in Canada [Retrieved 17 December 2019].

- Conway, John Frederick. The West: The History of a Region in Confederation. 3rd ed. Lorimer; 2005. ISBN 978-1-55028-905-3. p. 63–64, 85–100.

- Bercuson, David J. Confrontation at Winnipeg: Labour, Industrial Relations, and the General Strike. McGill-Queen's University Press; 1990. ISBN 978-0-7735-0794-4. p. 173–176.

- Lederman, Peter R. Sedition in Winnipeg: An Examination of the Trials for Seditious Conspiracy Arising from the General Strike of 1919. Queen's Law Journal. 1976;3(2):5, 14–17.

- Easterbrook, William Thomas; Aitken, Hugh GJ. Canadian economic history. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1988. ISBN 978-0-8020-6696-1. p. 493–494.

- Wiseman, Nelson. Social democracy in Manitoba. University of Manitoba; 1983. ISBN 978-0-88755-118-5. p. 13.

- Newman, Michael. February 19, 1942: If Day. Manitoba History. Spring 1987;(13).

- Haque, C Emdad. Risk Assessment, Emergency Preparedness and Response to Hazards: The Case of the 1997 Red River Valley Flood, Canada. Natural Hazards. May 2000;21(2):226–237. doi:10.1023/a:1008108208545.

- Hawkes, David C; Devine, Marina. Meech Lake and Elijah Harper: Native-State Relations in the 1990s. In: Abele, Frances. How Ottawa Spends, 1991–1992: The Politics of Fragmentation. McGill-Queen's University Press; 1991. ISBN 978-0-88629-146-4. p. 33–45.

- AODA Alliance. Please support a barrier-free Canada; 21 May 2015 [archived 16 April 2016].

- Winnipeg Census Metropolitan Area (CMA) with census subdivision (municipal) population breakdowns; 13 March 2007 [archived 16 January 2008; Retrieved 13 March 2007].

- Statistics Canada. 2006 Community Profiles Manitoba & Winnipeg [archived 14 June 2012; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- Statistics Canada. Ethnic Origin (247), Single and Multiple Ethnic Origin Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data [archived 28 October 2011; Retrieved 29 January 2010].

- Janzen, L. Native population fastest growing in country. 13 March 2002:B4.

- Government of Manitoba. Manitoba's Aboriginal Community: a 2001 to 2026 population & demographic profile; July 2005.

- Government of Manitoba. Icelandic Settlement, Gimli [archived 12 September 2011; Retrieved 8 March 2012].

- Statistics Canada. Religions in Canada [archived 9 September 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Statistics Canada. Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory [archived 20 April 2008; Retrieved 3 March 2010].

- Statistics Canada. Provincial and Territorial Economic Accounts Review; 11 April 2010 [archived 12 January 2012; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- Statistics Canada. Individuals by total income level, by province and territory; 11 February 2009 [archived 15 January 2011; Retrieved 7 November 2009].

- Statistics Canada. Latest release from the Labour Force Survey; 6 November 2009 [Retrieved 7 November 2009].

- University of Manitoba. A Century of Agriculture [archived 10 September 2008; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- New Simplot french fry plant in Canada expected to come on line later this year. Quick Frozen Foods International. 1 July 2002;2(3):3.

- A Case Study of the Canadian Oat Market. Alberta Agriculture, Food and Rural Development. November 2005 [archived 2 November 2011; Retrieved 29 January 2010]:74.

- Top 100 Companies Survey 2000. Manitoba Business Magazine. July 2000;26.

- Shackley, Myra L. Wildlife tourism. International Thomson Business Press; 1996. ISBN 978-0-415-11539-1. p. xviii.

- Hudson Bay Port Company. Port of Churchill [archived 26 September 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Benedictson, Megan (23 January 2018). "Business lobby says Manitoba most improved province for tackling red tape". CTV News Winnipeg. Archived from the original on 3 February 2018.

- Friesen, Gerald. The Canadian prairies: a history. University of Toronto Press; 1987. ISBN 978-0-8020-6648-0. p. 22–47, 66, 183–184.

- Morton, William L. Lord Selkirk Settlers. Manitoba Pageant. April 1962;7(3).

- Department of National Defence. Organization Overview [archived 5 December 2010; Retrieved 16 January 2010].

- Department of National Defence. 17 Wing—General Information [archived 11 June 2011; Retrieved 22 February 2010].

- Pigott, Peter. Taming the skies. Dundurn Press Ltd.; 2003. ISBN 978-1-55002-469-2. p. 203.

- Department of National Defence. CFB ASU Shilo [archived 5 March 2012; Retrieved 2 April 2012].

- Dupont, Jerry. The Common Law Abroad: Constitutional and Legal Legacy of the British Empire. Fred B Rothman & Co; 2000. ISBN 978-0-8377-3125-4. p. 139–142.

- Adams, Chris. Manitoba's Political Party Systems: An Historical Overview. Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association. 17 September 2006:2–23.

- Summers, Harrison Boyd. Unicameral Legislatures. Vol. 11. Wilson; 1936. OCLC 1036784. p. 9.

- Lieutenant-Governor of Manitoba. Roles and Responsibilities [archived 13 November 2009; Retrieved 29 October 2009].

- Hogg, Peter W. Necessity in Manitoba: The Role of Courts in Formative or Crisis Periods. In: Shetreet, Shimon. The Role of Courts in Society. Aspen Publishing; 1988. ISBN 978-90-247-3670-6. p. 9.

- Elections Manitoba. 41st General Election [Retrieved 29 October 2009].

- Elections Manitoba. 40th Provincial Election [archived 25 April 2012; Retrieved 8 March 2012].

- Megan Batchelor and Peter Chura. Manitoba premier kicks renegade MLA from caucus; 4 February 2014 [archived 5 March 2014; Retrieved 5 March 2014].

- Government of Canada. Members of Parliament [archived 24 April 2011; Retrieved 12 November 2009].

- Government of Canada. Senators [archived 24 February 2010; Retrieved 12 November 2009].

- Manitoba Courts. Provincial Court – Description of the Court's Work; 21 September 2006 [archived 22 April 2009; Retrieved 9 November 2009].

- Brawn, Dale. The Court of Queen's Bench of Manitoba, 1870–1950: A Biographical History. University of Toronto Press; 2006. ISBN 978-0-8020-9225-0. p. 16–20.

- Hebert, Raymond M. Manitoba's French-Language Crisis: A Cautionary Tale. McGill-Queen's University Press; 2005. ISBN 978-0-7735-2790-4. p. xiv–xvi, 11–12, 30, 67–69.

- In [1992] 1 S.C.R. 221–222 scc-csc.lexum.com Archived 20 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine, the Supreme Court rejected the contentions of the Société Franco-manitobaine that §23 extends to executive functions of the executive branch.

- Government of Manitoba. Manitoba Francophone Affairs Secretariat [archived 24 May 2010; Retrieved 29 October 2009].

- Statistics Canada. Population by knowledge of official language, by province and territory (2006 Census); 11 December 2007 [archived 15 January 2011; Retrieved 8 March 2010].

- Web2.gov.mb.ca. The Aboriginal Languages Recognition Act; 17 June 2010 [archived 11 April 2013; Retrieved 31 March 2013].

- Government of Manitoba. Employment [archived 8 September 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Government of Manitoba. Transportation & Logistics [archived 8 September 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- CBC News. Winnipeg bus depot to move after 45 years downtown; 14 August 2009 [Retrieved 31 January 2010].

- Government of Manitoba. Transportation: Winnipeg James Armstrong Richardson International Airport [archived 27 May 2009; Retrieved 28 October 2009].

- Winnipeg Airports Authority. Winnipeg Airports Authority Officially Opens Community's New Front Door; 31 October 2011 [archived 11 December 2011; Retrieved 9 March 2012].

- Badertscher, John M. Religious Studies in Manitoba and Saskatchewan. Wilfrid Laurier University Press; 1993. ISBN 978-0-88920-223-8. p. 8.

- Bale, Gordon. Law, Politics, and the Manitoba School Question: Supreme Court and Privy Council. Canadian Bar Review. 1985;63(461):467–473.

- Oreopoulos, Philip. Oreopoulos. Conference on Education, Schooling and The Labour Market. May 2003:9.

- Hajnal, Vivian J. Canadian Approaches to the Financing of School Infrastructure. In: Crampton, Faith E; Thompson, David C. Saving America's School Infrastructure. Information Age Publishing; 2003. ISBN 978-1-931576-17-8. p. 57–58.

- Government of Manitoba. Funded Independent Schools [archived 6 December 2009; Retrieved 12 November 2009].

- Government of Manitoba. Non-Funded Independent Schools [archived 6 December 2009; Retrieved 12 November 2009].

- Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada. Canadian Universities [archived 31 October 2008; Retrieved 8 October 2008].

- AUCC. Founding Year and Joining Year of AUCC Member Institutions; 2 November 2009 [archived 7 August 2011; Retrieved 2 February 2010].

- Manitoba Library Association. Directory of libraries in Manitoba [archived 1 June 2009; Retrieved 29 October 2009].

- Winnipeg Public Library: A Capsule History. Winnipeg Public Library; 1988.

- Government of Manitoba. Culture, Heritage and Tourism [archived 27 April 2011; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- Bolton, David. The Red River Jig. Manitoba Pageant. September 1961;7(1).

- Lederman, Anne. Old Indian and Metis Fiddling in Manitoba: Origins, Structure, and Questions of Syncretism. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies. 1988;7(2):205–230.

- Dafoe, Christopher. Dancing through time: the first fifty years of Canada's Royal Winnipeg Ballet. Portage & Main Press; 1990. ISBN 978-0-9694264-0-0. p. 4, 10, 154.

- Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra. More About the WSO; 2008 [archived 4 May 2008; Retrieved 23 February 2010].

- Moss, Jane. The Drama of Identity in Canada's Francophone West. American Review of Canadian Studies. Spring 2004;34(1):82–83. doi:10.1080/02722010409481686.

- Hendry, Thomas B. Trends in Canadian Theatre. The Tulane Drama Review. Autumn 1965;10(1):65.

- Manitoba Theatre for Young People. About Us [archived 6 July 2011; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- University of Manitoba. Winnipeg Art Gallery [archived 22 October 2009; Retrieved 8 November 2009].

- Winnipeg Art Gallery. History; 2009 [archived 25 October 2009; Retrieved 8 November 2009].

- Elliott, Robin. Before the Gold Rush: Flashbacks to the Dawn of the Canadian Sound. CAML Review. December 1998;26(3):26–27.

- Melhuish, Martin. Bachman-Turner Overdrive: Rock Is My Life, This Is My Song. Methuen Publications; 1976. ISBN 978-0-8467-0104-0. p. 74.

- The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc.. Neil Young; 2007 [archived 29 March 2010; Retrieved 23 February 2010].

- Bianco, David P. Parents aren't supposed to like it. 2nd ed. Vol. 1. U*X*L; 2001. ISBN 978-0-7876-1732-5. p. 42.

- Manitoba Film & Music. Who's filmed here? [archived 14 December 2009; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. 80th Annual Academy Awards Oscar Nominations Fact Sheet [archived 16 November 2009; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- St. Germain, Pat. Falcon Beach filming again in Manitoba. 21 June 2006 [archived 6 July 2011; Retrieved 11 November 2009]. Winnipeg Sun.

- Canada Council for the Arts. Cumulative List of Winners of the Governor General's Literary Awards; 2008 [archived 2 November 2011; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Astor, Dave. Lynn Johnston to Enter Canadian Cartoonists' Hall of Fame on Friday; 6 August 2008 [Retrieved 5 September 2008]. Alt URL

- Rosenthal, Caroline. Collective Memory and Personal Identity in the Prairie town of Manawaka. In: Reingard M. Nischik. The Canadian Short Story: Interpretations. Camden House; 2007. ISBN 978-1-57113-127-0. p. 219.

- Werlock, Abby. Carol Shields's the Stone Diaries. Continuum; 2001. ISBN 978-0-8264-5249-8. p. 69.

- Bank of Canada. Gabrielle Roy, Canadian author of the quotation on the back of the new $20 note [archived 25 October 2012; Retrieved 2 April 2012].

- "From Plain People to Plains People: Mennonite Literature from the Canadian Prairies". American Studies Journal. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Selwood, John. The lure of food: food as an attraction in destination marketing in Manitoba, Canada. In: Hall, C Michael; Sharples, Liz; Mitchell, Richard; Macionis, Niki; Cambourne, Brock. Food Tourism Around The World: Development, Management and Markets. Butterworth-Heinemann; 2003. ISBN 978-0-7506-5503-3. p. 180–182.

- Folklorama. FAQs [archived 11 August 2010; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Woosnam, Kyle M; McElroy, Kerry E; Van Winkle, Christine M. The Role of Personal Values in Determining Tourist Motivations: An Application to the Winnipeg Fringe Theatre Festival, a Cultural Special Event. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management. July 2009;18(5):500–502. doi:10.1080/19368620902950071.

- Dutton, Lee S. Anthropological Resources: A Guide to Archival, Library, and Museum Collections. Routledge; 1999. ISBN 978-0-8153-1188-1. p. 6–9.

- Barbour, Alex; Collins, Cathy; Grattan, David. Monitoring the Nonsuch. LIC-CG Annual Conference. 1986;12:19–21.

- Manitoba Children's Museum. About MCM [archived 2 October 2010; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Stewart, Jane. Winnipeg: a big city with the heart of a small town. Canadian Medical Association Journal. April 1986;134(7):810.

- Janzic, A; Hatcher, J. Late Cretaceous Marine Reptile Fossils of the Canadian Fossil Discovery Centre. Vol. Abstracts Volume. Mount Royal College; 2008. (Alberta Palaeontological Society, Twelfth Annual Symposium). p. 28.

- Bingham, Russell; Baird, Daniel. Canadian Museum for Human Rights; 26 March 2015 [archived 4 November 2016].

- Collections Canada. Canadian Ethnic Newspapers Currently Received [archived 7 January 2008; Retrieved 17 July 2009].

- Economic Development Brandon. Local Media [archived 4 January 2010; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Legislative Library. Current Newspapers at the Library [archived 11 August 2010; Retrieved 23 February 2010].

- Carlin, Vincent A. No Clear Channel: The Rise and Possible Fall of Media Convergence. In: Frits Pannekoek, David Taras, Maria Bakardjieva. How Canadians communicate. Vol. 1. University of Calgary Press; 2003. ISBN 978-1-55238-104-5. p. 59–60.

- Fresh Traffic Group. Winnipeg Radio; 2008 [archived 20 April 2009; Retrieved 11 November 2009].

- Smith, John H. The Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. International Communication Gazette. 1969;15:139–143. doi:10.1177/001654926901500205.

- Buddle, Kathleen. Aboriginal Cultural Capital Creation and Radio Production in Urban Ontario. Canadian Journal of Communication. 2005;30(1):29–30.

- Helyar, John. Latest Example of an NHL Trend Is the Flight of the Winnipeg Jets. 26 April 1996 [archived 10 October 2017; Retrieved 22 May 2009]. The Wall Street Journal.

- Traikos, Michael. It's official: the Winnipeg Jets are back. National Post. 24 June 2011 [archived 15 July 2012; Retrieved 8 March 2012].

- Canada West Universities Athletic Association. About Canada West; 2006 [archived 25 April 2011; Retrieved 11 April 2011].

- World's biggest bonspiel open to women curlers in 2014. 10 April 2012 [archived 14 December 2012; Retrieved 2 December 2012]. Winnipeg Free Press.

- Canadian Athletes: The Greatest Athletes Canada Has Ever Produced. 22 November 2012 [archived 16 February 2013]. Huffington Post Canada.

Further reading

- Donnelly, MS. The Government of Manitoba. University of Toronto Press; 1963.

- Hanlon, Christine; Edie, Barbara; Pendgracs, Doreen. Manitoba Book of Everything. MacIntyre Purcell Publishing Inc.; 2008. ISBN 978-0-9784784-5-2.

- Whitcomb, Ed. A Short History of Manitoba. Canada's Wings; 1982. ISBN 978-0-920002-15-5.