Beluga whale

The beluga whale (/bɪˈluːɡə/) (Delphinapterus leucas) is an Arctic and sub-Arctic cetacean. It is one of two members of the family Monodontidae, along with the narwhal, and the only member of the genus Delphinapterus. It is also known as the white whale, as it is the only cetacean of this colour; the sea canary, due to its high-pitched calls; and the melonhead, though that more commonly refers to the melon-headed whale, which is an oceanic dolphin.

| Beluga whale[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| At Georgia Aquarium | |

| |

| Size compared to an average human | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Infraorder: | Cetacea |

| Family: | Monodontidae |

| Genus: | Delphinapterus Lacépède, 1804 |

| Species: | D. leucas |

| Binomial name | |

| Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, 1776) | |

| |

| Beluga range | |

The beluga is adapted to life in the Arctic, so it has anatomical and physiological characteristics that differentiate it from other cetaceans. Amongst these are its all-white colour and the absence of a dorsal fin, which allows it to swim under ice with ease.[3] It possesses a distinctive protuberance at the front of its head which houses an echolocation organ called the melon, which in this species is large and deformable. The beluga's body size is between that of a dolphin and a true whale, with males growing up to 5.5 m (18 ft) long and weighing up to 1,600 kg (3,530 lb). This whale has a stocky body. Like many cetaceans, a large percentage of its weight is blubber (subcutaneous fat). Its sense of hearing is highly developed and its echolocation allows it to move about and find breathing holes under sheet ice.

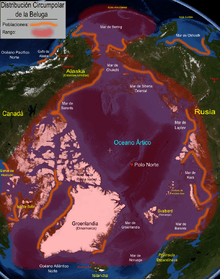

Belugas are gregarious and form groups of 10 animals on average, although during the summer, they can gather in the hundreds or even thousands in estuaries and shallow coastal areas. They are slow swimmers, but can dive to 700 m (2,300 ft) below the surface. They are opportunistic feeders and their diets vary according to their locations and the season. The majority of belugas live in the Arctic Ocean and the seas and coasts around North America, Russia and Greenland; their worldwide population is thought to number around 150,000. They are migratory and the majority of groups spend the winter around the Arctic ice cap; when the sea ice melts in summer, they move to warmer river estuaries and coastal areas. Some populations are sedentary and do not migrate over great distances during the year.

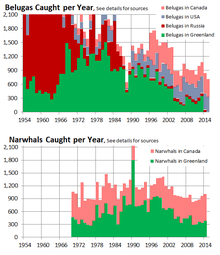

The native peoples of North America and Russia have hunted belugas for many centuries. They were also hunted by non-natives during the 19th century and part of the 20th century. Hunting of belugas is not controlled by the International Whaling Commission, and each country has developed its own regulations in different years. Currently some Inuit in Canada and Greenland, Alaska Native groups and Russians are allowed to hunt belugas to consume and sell; aboriginal whaling is excluded from the International Whaling Commission 1986 moratorium on hunting. The numbers have dropped substantially in Russia and Greenland, but not in Alaska and Canada. Other threats include natural predators (polar bears and killer whales), contamination of rivers (as with Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCBs) which bioaccumulate up the food chain) and infectious diseases. The beluga was placed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature's Red List in 2008 as being "near threatened"; the subpopulation from the Cook Inlet in Alaska, however, is considered critically endangered and is under the protection of the United States' Endangered Species Act. Of seven Canadian beluga populations, those inhabiting eastern Hudson Bay, Ungava Bay and the St. Lawrence River are listed as endangered.

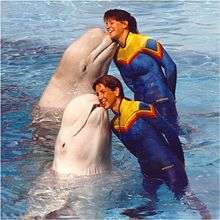

Belugas are one of the most commonly kept cetaceans in captivity and are housed in aquariums, dolphinariums and wildlife parks in North America, Europe and Asia. They are popular with the public due to their colour and expression.

Taxonomy

The beluga was first described in 1776 by Peter Simon Pallas.[1] It is a member of the Monodontidae family, which is in turn part of the parvorder Odontoceti (toothed whales).[1] The Irrawaddy dolphin was once placed in the same family, though recent genetic evidence suggests these dolphins belong to the family Delphinidae.[4][5] The narwhal is the only other species within the Monodontidae besides the beluga.[6] A skull has been discovered with intermediate characteristics supporting the hypothesis that hybridisation is possible between these two species.[7]

The name of the genus, Delphinapterus, means "dolphin without fin" (from the Greek δελφίν (delphin), dolphin and απτερος (apteros), without fin) and the species name leucas means "white" (from the Greek λευκας (leukas), white).[8] The Red List of Threatened Species gives both beluga and white whale as common names, though the former is now more popular. The English name comes from the Russian белуха (belukha), which derives from the word белый (bélyj), meaning "white".[8] The name beluga in Russian refers to an unrelated species, a fish, the beluga sturgeon.

The whale is also colloquially known as the sea canary on account of its high-pitched squeaks, squeals, clucks and whistles. A Japanese researcher says he taught a beluga to "talk" by using these sounds to identify three different objects, offering hope that humans may one day be able to communicate effectively with sea mammals.[9] A similar observation has been made by Canadian researchers, where a beluga which died in 2007 "talked" when he was still a subadult. Another example is NOC, a beluga whale that could mimic the rhythm and tone of human language. Beluga whales in the wild have been reported to imitate human voices.[10]

Evolution

Mitochondrial DNA studies have shown modern cetaceans last shared a common ancestor between 25 and 34 million years ago[11][12] The superfamily Delphinoidea (which contains monodontids, dolphins and porpoises) split from other toothed whales, odontoceti, between 11 and 15 million years ago. Monodontids then split from dolphins (Delphinidae) and later from porpoises (Phocoenidae), their closest relatives in evolutionary terms.[11] In 2017 the genome of a beluga whale was sequenced, comprising 2.327 Gbp of assembled genomic sequence that encoded 29,581 predicted genes.[13] The authors estimated that the genome-wide sequence similarity between beluga whales and killer whales to be 97.87% ± 2.4 × 10−7% (mean ± standard deviation).

The beluga's earliest known distinctive ancestors include the prehistoric Denebola brachycephala from the late Miocene epoch (9–10 million years ago),[14][15] and Bohaskaia monodontoides, from the early Pliocene (3–5 million years ago).[16] Fossil evidence from Baja California[17] and Virginia indicate the family once inhabited warmer waters.[16] A fossil of the monodontid Casatia thermophila, from five million years ago, provides the strongest evidence that monodontids once inhabited warmer waters, as the fossil was found alongside fossils of tropical species such as bull and tiger sharks.[18]

The fossil record also indicates that, in comparatively recent times, the beluga's range varied with that of the polar ice packs expanding during ice ages and contracting when the ice retreated.[19] Counter-evidence to this theory comes from the finding in 1849 of fossilised beluga bones in Vermont in the United States, 240 km (150 mi) from the Atlantic Ocean. The bones were discovered during construction of the first railroad between Rutland and Burlington in Vermont, when workers unearthed the bones of a mysterious animal in Charlotte. Buried nearly 10 ft (3.0 m) below the surface in a thick blue clay, these bones were unlike those of any animal previously discovered in Vermont. Experts identified the bones as those of a beluga. Because Charlotte is over 150 mi (240 km) from the nearest ocean, early naturalists were at a loss to explain the presence of the bones of a marine mammal buried beneath the fields of rural Vermont.

The remains were found to be preserved in the sediments of the Champlain Sea, an extension of the Atlantic Ocean within the continent resulting from the rise in sea level at the end of the ice ages some 12,000 years ago.[20] Today, the Charlotte whale is the official Vermont State Fossil (making Vermont the only state whose official fossil is that of a still extant animal).[21]

Description

Its body is round, particularly when well fed, and tapers less smoothly to the head than the tail. The sudden tapering to the base of its neck gives it the appearance of shoulders, unique among cetaceans. The tail-fin grows and becomes increasingly and ornately curved as the animal ages. The flippers are broad and short—making them almost square-shaped.

Longevity

Preliminary investigations suggested a beluga's life expectancy was rarely more than 30 years.[22] The method used to calculate the age of a beluga is based on counting the layers of dentin and dental cement in a specimen's teeth, which were originally thought to be deposited once or twice a year. The layers can be readily identified as one layer consists of opaque dense material and the other is transparent and less dense. It is therefore possible to estimate the age of the individual by extrapolating the number of layers identified and the estimated frequency with which the deposits are laid down.[23] A 2006 study using radiocarbon dating of the dentin layers showed the deposit of this material occurs with a lesser frequency (once per year) than was previously thought. The study therefore estimated belugas can live for 70 or 80 years.[24]However, recent studies suggest that it is unclear as to whether belugas receive a different number of layers per year depending on the age of the animal (for example young belugas may only receive an additional one layer per year), or simply just one layer per year or every other year. [25]

Size

The species presents a moderate degree of sexual dimorphism, as the males are 25% longer than the females and are sturdier.[26] Adult male belugas can range from 3.5 to 5.5 m (11 to 18 ft), while the females measure 3 to 4.1 m (9.8 to 13.5 ft).[27] Males weigh between 1,100 and 1,600 kg (2,430 and 3,530 lb), and occasionally up to 1,900 kg (4,190 lb) while females weigh between 700 and 1,200 kg (1,540 and 2,650 lb).[28][29] They rank as mid-sized species among toothed whales.[30]

Individuals of both sexes reach their maximum size by the time they are 10 years old.[31] The beluga's body shape is stocky and fusiform (cone-shaped with the point facing backwards), and they frequently have folds of fat, particularly along the ventral surface.[32] Between 40% and 50% of their body weight is fat, which is a higher proportion than for cetaceans that do not inhabit the Arctic, where fat only represents 30% of body weight.[33][34] The fat forms a layer that covers all of the body except the head, and it can be up to 15 cm (5.9 in) thick. It acts as insulation in waters with temperatures between 0 and 18 °C, as well as being an important reserve during periods without food.[35]

Colour

The adult beluga is rarely mistaken for any other species, because it is completely white or whitish-grey in colour.[36] Calves are usually born grey,[27] and by the time they are a month old, have turned dark grey or blue grey. They then start to progressively lose their pigmentation until they attain their distinctive white colouration, at the age of seven years in females and nine in males.[36] The white colouration of the skin is an adaptation to life in the Arctic that allows belugas to camouflage themselves in the polar ice caps as protection against their main predators, polar bears and killer whales.[37] Unlike other cetaceans, the belugas seasonally shed their skin.[38] During the winter, the epidermis thickens and the skin can become yellowish, mainly on the back and fins. When they migrate to the estuaries during the summer, they rub themselves on the gravel of the riverbeds to remove the cutaneous covering.[38]

Head and neck

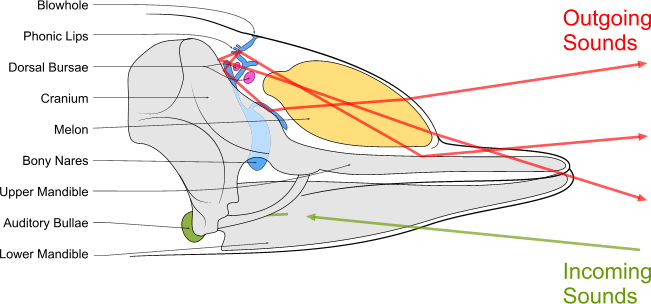

Like most toothed whales, it has a compartment found at the centre of the forehead that contains an organ used for echolocation called a melon, which contains fatty tissue.[39] The shape of the beluga's head is unlike that of any other cetacean, as the melon is extremely bulbous, lobed and visible as a large frontal prominence.[39] Another distinctive characteristic it possesses is the melon is malleable; its shape is changed during the emission of sounds.[6] The beluga is able to change the shape of its head by blowing air around its sinuses to focus the emitted sounds.[40][41] This organ contains fatty acids, mainly isovaleric acid (60.1%) and long-chain branched acids (16.9%), a very different composition from its body fat, and which could play a role in its echolocation system.[42]

Unlike many dolphins and whales, the seven vertebrae in the neck are not fused together, allowing the animal to turn its head laterally without needing to rotate its body.[43] This gives the head a lateral manoeuvrability that allows an improved field of view and movement and helps in catching prey and evading predators in deep water.[37] The rostrum has about eight to ten small, blunt and slightly curved teeth on each side of the jaw and a total of 36 to 40 teeth.[44] Belugas do not use their teeth to chew, but for catching hold of their prey; they then tear them up and swallow them nearly whole.[45]

Belugas only have a single spiracle, which is located on the top of the head behind the melon, and has a muscular covering, allowing it to be completely sealed. Under normal conditions, the spiracle is closed and an animal must contract the muscular covering to open the spiracle.[46] A beluga's thyroid gland is larger than that of terrestrial mammals—weighing three times more than that of a horse—which helps it to maintain a greater metabolism during the summer when it lives in river estuaries.[47] It is the marine cetacean that most frequently develops hyperplastic and neoplastic lesions of the thyroid.[48]

Fins

The fins retain the bony vestiges of the beluga's mammalian ancestors, and are firmly bound together by connective tissue.[32] The fins are small in relation to the size of the body, rounded and oar-shaped and slightly curled at the tips.[8] These versatile extremities are mainly used as a rudder to control direction, to work in synchrony with the tailfin and for agile movement in shallow waters up to 3 m (9.8 ft) deep.[31] The fins also contain a mechanism for regulating body temperature, as the arteries feeding the fin's muscles are surrounded by veins that dilate or contract to gain or lose heat.[32][49] The tailfin is flat with two oar-like lobes, it does not have any bones, and is made up of hard, dense, fibrous connective tissue. The tailfin has a distinctive curvature along the lower edge.[32] The longitudinal muscles of the back provide the ascending and descending movement of the tailfin, which has a similar thermoregulation mechanism to the pectoral fins.[32]

Belugas have a dorsal ridge, rather than a dorsal fin.[27] The absence of the dorsal fin is reflected in the genus name of the species—apterus the Greek word for "wingless". The evolutionary preference for a dorsal ridge rather than a fin is believed to be an adaptation to under-ice conditions, or possibly as a way of preserving heat.[6] The crest is hard and, along with the head, can be used to open holes in ice up to 8 cm (3.1 in) thick.[50]

Senses

The beluga has a very specialised sense of hearing and its auditory cortex is highly developed. It can hear sounds within the range of 1.2 to 120 kHz, with the greatest sensitivity between 10 and 75 kHz,[51] where the average hearing range for humans is 0.02 to 20 kHz.[52] The majority of sounds are most probably received by the lower jaw and transmitted towards the middle ear. In the toothed whales, the lower jawbone is broad with a cavity at its base, which projects towards the place where it joins the cranium. A fatty deposit inside this small cavity connects to the middle ear.[53] Toothed whales also possess a small external auditory hole a few centimetres behind their eyes; each hole communicates with an external auditory conduit and an eardrum. It is not known if these organs are functional or simply vestigial.[53]

Belugas are able to see within and outside of water, but their vision is relatively poor when compared to dolphins.[54] Their eyes are especially adapted to seeing under water, although when they come into contact with the air, the crystalline lens and the cornea adjust to overcome the associated myopia (the range of vision under water is short).[54] A beluga's retina has cones and rods, which also suggests they can see in low light. The presence of cone cells indicates they can see colours, although this suggestion has not been confirmed.[54] Glands located in the medial corner of their eyes secrete an oily, gelatinous substance that lubricates the eye and helps flush out foreign bodies. This substance forms a film that protects the cornea and the conjunctiva from pathogenic organisms.[54]

Studies on captive animals show they seek frequent physical contact with other belugas.[37] Areas in the mouth have been found that could act as chemoreceptors for different tastes, and they can detect the presence of blood in water, which causes them to react immediately by displaying typical alarm behaviour.[37] Like the other toothed whales, their brains lack olfactory bulbs and olfactory nerves, which suggests they do not have a sense of smell.[39]

Behaviour

Social structure and play

These cetaceans are highly sociable and they regularly form small groups, or pods, that may contain between two and 25 individuals, with an average of 10 members.[55] Pods tend to be unstable, meaning individuals tend to move from pod to pod. Radio tracking has even shown belugas can start out in one pod and within a few days be hundreds of miles away from that pod.[56] Beluga whale pods can be grouped into three categories, nurseries (which consist of mother and calves), bachelors (which consist of all males) and mixed groups. Mixed groups contain animals of both sexes.[57][44] Many hundreds and even thousands of individuals can be present when the pods join together in river estuaries during the summer. This can represent a significant proportion of the total population and is when they are most vulnerable to being hunted.[58]

They are cooperative animals and frequently hunt in coordinated groups.[59] The animals in a pod are very sociable and often chase each other as if they are playing or fighting, and they often rub against each other.[60] Often individuals will surface and dive together in a synchronized manner, in a behavior known as milling.

In captivity, they can be seen to be constantly playing, vocalising and swimming around each other.[61] In one case, one whale blew bubbles, while the other one popped them. There have also been reports of beluga whales copying and imitating one another, similar to a game of Simon-says. Individuals have also been reported them displaying physical affection, via mouth to mouth contact.[62] They also show a great deal of curiosity towards humans and frequently approach the windows in the tanks to observe them.[63]

Belugas also show a great degree of curiosity towards humans in the wild, and frequently swim alongside boats.[64] They also play with objects they find in the water; in the wild, they do this with wood, plants, dead fish and bubbles they have created.[33] During the breeding season, adults have been observed carrying objects such as plants, nets, and even the skeleton of a dead reindeer on their heads and backs.[61] Captive females have also been observed displaying this behavior, carrying items such as floats and buoys, after they have lost a calf. Experts consider this interaction with the objects to be a substitute behavior.[65]

In captivity, mothering behavior among belugas depends on the individual. Some mothers are extremely attentive while other mothers are so blasé, that they have actually lost their calves. In aquaria, there have been cases where dominant females have stolen calves from mothers, particularly if they have lost a calf or if they are pregnant. After giving birth, dominant females will return the calf back to their mother. Additionally, male calves will temporarily leave their mothers to interact with an adult male who can serve as a role model for the calf, before they return to their mothers. Male calves are also frequently seen interacting with each other.[66]

Swimming and diving

Belugas are slower swimmers than the other toothed whales, such as the killer whale and the common bottlenose dolphin, because they are less hydrodynamic and have limited movement of their tail-fins, which produce the greatest thrust.[67] They frequently swim at speeds between 3 and 9 km/h (1.9 and 5.6 mph), although they are able to maintain a speed of 22 km/h for up to 15 min.[44] Unlike most cetaceans, they are capable of swimming backwards.[31][68] Belugas swim on the surface between 5% and 10% of the time, while for the rest of the time they swim at a depth sufficient enough to cover their bodies.[31] They do not jump out of the water like dolphins or killer whales.[8]

These animals usually only dive to depths to 20 m (66 ft),[69] although they are capable of diving to greater depths. Individual captive animals have been recorded at depths between 400 and 647 m below sea level,[70] while animals in the wild have been recorded as diving to a depth of more than 700 m, with the greatest recorded depth being over 900 m.[71] A dive normally lasts 3 to 5 minutes, but can last up to over 20 minutes.[72][44][71][73] In the shallower water of the estuaries, a diving session may last around two minutes; the sequence consists of five or six rapid, shallow dives followed by a deeper dive lasting up to one minute.[31] The average number of dives per day varies between 31 and 51.[71]

All cetaceans, including belugas, have physiological adaptations designed to conserve oxygen while they are under water.[74] During a dive, these animals will reduce their heart rate from 100 beats a minute to between 12 and 20.[74] Blood flow is diverted away from certain tissues and organs and towards the brain, heart and lungs, which require a constant oxygen supply.[74] The amount of oxygen dissolved in the blood is 5.5%, which is greater than that found in land-based mammals and is similar to that of Weddell seals (a diving marine mammal). One study found a female beluga had 16.5 L of oxygen dissolved in her blood.[75] Lastly, the beluga's muscles contain high levels of the protein myoglobin, which stores oxygen in muscle. Myoglobin concentrations in belugas are several times greater than for terrestrial mammals, which help prevent oxygen deficiency during dives.[76]

Beluga whales often accompany bowhead whales, for curiosity and to secure polynya feasibility to breathe as bowheads are capable of breaking through ice from underwater by headbutting.[77]

Diet

Belugas play an important role in the structure and function of marine resources in the Arctic Ocean, as they are the most abundant toothed whales in the region.[78] They are opportunistic feeders; their feeding habits depend on their locations and the season.[26] For example, when they are in the Beaufort Sea, they mainly eat Arctic cod (Boreogadus saida) and the stomachs of belugas caught near Greenland were found to contain rose fish (Sebastes marinus), Greenland halibut (Reinhardtius hippoglossoides) and northern shrimp (Pandalus borealis),[79] while in Alaska their staple diet is Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch).[80] In general, the diets of these cetaceans consist mainly of fish; apart from those previously mentioned, other fish they feed on include capelin (Mallotus villosus), smelt, sole, flounder, herring, sculpin and other types of salmon.[81] They also consume a great quantity of invertebrates, such as shrimp, squid, crabs, clams, octopus, sea snails, bristle worms and other deep-sea species.[81][82] Belugas feed mainly in winter as their blubber is thickest in later winter and early spring, and thinnest in the fall. Inuit observation has led scientists to believe that belugas do not hunt during migration, at least in Hudson Bay [83]

The diet of Alaskan belugas is quite diverse and varies depending on season and migratory behavior. Belugas in the Beaufort Sea mainly feed on staghorn and shorthorn sculpin, walleye pollock, Arctic cod, saffron cod and Pacific sand lance. Shrimp are the most common invertebrate eaten, with octopus, amphipods and echiurids being other sources of invertebrate prey.The most common prey species for belugas in the Eastern Chukchi Sea appears to be shrimp, echiurid worms, cephalopods and polychaetas. The largest prey item consumed by beluga whales in the Eastern Chukchi Sea seems to be saffron cod. Beluga whales in the Eastern Bering Sea feed on a variety of fish species including saffron cod, rainbow smelt, walleye pollock, Pacific salmon, Pacific Herring and several species of flounder and sculpin. The primary invertebrate consumed is shrimp.The primary prey item in regard to fish species for belugas in Bristol Bay appears to be the five species of salmon, with sockeye being the most prevalent. Smelt is also another common fish family eaten by belugas in this region. Shrimp is the most prevalent invertebrate prey item. The most common prey items for belugas in Cook Inlet appear to be salmon, cod and smelt.[84]

Animals in captivity eat 2.5% to 3.0% of their body weight per day, which equates to 18.2 to 27.2 kg.[85] Like their wild counterparts, captive belugas were found to eat less in the fall. [86]

Foraging on the seabed typically takes place at depths between 20 and 40 m,[87] although they can dive to depths of 700 m in search of food.[71] Their flexible necks provide a wide range of movement while they are searching for food on the ocean floor. Some animals have been observed to suck up water and then forcefully expel it to uncover their prey hidden in the silt on the seabed.[59] As their teeth are neither large nor sharp, belugas must use suction to bring their prey into their mouths; it also means their prey has to be consumed whole, which in turn means it cannot be too large or the belugas run the risk of it getting stuck in their throats.[88] They also join together into coordinated groups of five or more to feed on shoals of fish by steering the fish into shallow water, where the belugas then attack them.[59] For example, in the estuary of the Amur River, where they mainly feed on salmon, groups of six or eight individuals join together to surround a shoal of fish and prevent their escape. Individuals then take turns feeding on the fish.[50]

Reproduction

Estimations of the age of sexual maturity for beluga whales vary considerably; the majority of authors estimate males reach sexual maturity when they are between nine and fifteen years old, and females reach maturity when they are between eight and fourteen years old.[89] The average age at which females first give birth is 8.5 years and fertility begins to decrease when they are 25, eventually undergoing menopause,[90] and ceasing reproductive potential with no births recorded for females older than 41.[89]

Female belugas typically give birth to one calf every three years.[27] Most mating occurs usually February through May, but some mating occurs at other times of year.[6] The beluga may have delayed implantation.[6] Gestation has been estimated to last 12.0 to 14.5 months,[27] but information derived from captive females suggests a longer gestation period up to 475 days (15.8 months).[91] During the mating season, the testes mass of belugas will double in weight. Testosterone levels increase, but seems to be independent of copulation. Copulation typically takes place between 3 and 4 AM. [92]

Calves are born over a protracted period that varies by location. In the Canadian Arctic, calves are born between March and September, while in Hudson Bay, the peak calving period is in late June, and in Cumberland Sound, most calves are born from late July to early August.[93] Births usually take place in bays or estuaries where the water is warm with a temperature of 10 to 15 °C.[55] Newborns are about 1.5 m (4 ft 11 in) long, weigh about 80 kg (180 lb), and are grey in colour.[44] They are able to swim alongside their mothers immediately after birth.[94] The newborn calves nurse under water and initiate lactation a few hours after birth; thereafter, they feed at intervals around an hour.[59] Studies of captive females have indicated their milk composition varies between individuals and with the stage of lactation; it has an average content of 28% fat, 11% protein, 60.3% water, and less than 1% residual solids.[95] The milk contains about 92 cal per ounce.[96]

The calves remain dependent on their mothers for nursing for the first year, when their teeth appear.[55] After this, they start to supplement their diets with shrimp and small fish.[39] The majority of the calves continue nursing until they are 20 months old, although occasionally lactation can continue for more than two years,[44] and lactational anoestrus may not occur. Alloparenting (care by females different from the mother) has been observed in captive belugas, including spontaneous and long-term milk production. This suggests this behaviour, which is also seen in other mammals, may be present in belugas in the wild.[97]

Hybrids have been documented between the beluga and the narwhal (specifically offspring conceived by a beluga father and a narwhal mother), as one, perhaps even as many as three, such hybrids were killed and harvested during a sustenance hunt. Whether or not these hybrids could breed remains unknown. The unusual dentition seen in the single remaining skull indicates the hybrid hunted on the seabed, much as walruses do, indicating feeding habits different from those of either parent species.[98][99]

Communication and echolocation

Belugas use sounds and echolocation for movement, communication, to find breathing holes in the ice, and to hunt in dark or turbid waters.[40] They produce a rapid sequence of clicks that pass through the melon, which acts as an acoustic lens to focus the sounds into a beam that is projected forward through the surrounding water.[96] These sounds spread through the water at a speed of nearly 1.6 km per second, some four times faster than the speed of sound in air. The sound waves reflect from objects and return as echoes that are heard and interpreted by the animal.[40] This enables them to determine the distance, speed, size, shape and the object's internal structure within the beam of sound. They use this ability when moving around thick Arctic ice sheets, to find areas of unfrozen water for breathing, or air pockets trapped under the ice.[55]

Some evidence indicates that belugas are highly sensitive to noise produced by humans. In one study, the maximum frequencies produced by an individual located in San Diego Bay, California, were between 40 and 60 kHz. The same individual produced sounds with a maximum frequency of 100 to 120 kHz when transferred to Kaneohe Bay in Hawaii. The difference in frequencies is thought to be a response to the difference in environmental noise in the two areas.[100]

These animals communicate using sounds of high frequency; their calls can sound like bird songs, so belugas were nicknamed "canaries of the sea".[101] Like the other toothed whales, belugas do not possess vocal cords and the sounds are probably produced by the movement of air between the nasal sacks, which are located near to the blowhole.[40]

As a, toothed whale, beluga calls can be broken down into the categories of whistles, clicks and burst calls. Whistles tend to indicate social communication while clicks indicate navigation and foraging. Burst calls tend to indicate aggression. [102]

Belugas are among the most vocal cetaceans.[103] They use their vocalisations for echolocation, during mating and for communication. They possess a large repertoire, emitting up to 11 different sounds, such as cackles, whistles, trills and squawks.[40] They make sounds by grinding their teeth or splashing, but they rarely use body language to make visual displays with their pectoral fins or tailfins, nor do they perform somersaults or jumps in the way other species do, such as dolphins.[40]

There is heavy debate as to whether cetacean vocalizations can constitute a language. A study conducted in 2015 determined that European beluga signals share physical features comparable to “vowels.” These sounds were found to be stable throughout time, but varied among different geographical locations. The further away the populations were from each other, the more varied the sounds were in relation to one another. [104]

Distribution

The beluga inhabits a discontinuous circumpolar distribution in Arctic and sub-Arctic waters.[105] During the summer, they can mainly be found in deep waters ranging from 76°N to 80°N, particularly along the coasts of Alaska, northern Canada, western Greenland and northern Russia.[105] The southernmost extent of their range includes isolated populations in the St. Lawrence River in the Atlantic,[106] and the Amur River delta, the Shantar Islands and the waters surrounding Sakhalin Island in the Sea of Okhotsk.[107]

Migration

_(20332437900).jpg)

Belugas have a seasonal migratory pattern.[108] Migration patterns are passed from parents to offspring. Some travel as far as 6,000 kilometres per year.[109] When the summer sites become blocked with ice during the autumn, they move to spend the winter in the open sea alongside the pack ice or in areas covered with ice, surviving by using polynyas to surface and breathe.[110] In summer after the sheet ice has melted, they move to coastal areas with shallower water (1–3 m deep), although sometimes they migrate towards deeper waters (>800 m).[108] In the summer, they occupy estuaries and the waters of the continental shelf, and, on occasion, they even swim up the rivers.[108] A number of incidents have been reported where groups or individuals have been found hundreds or even thousands of kilometres from the ocean.[111][112] One such example comes from June 9, 2006, when a young beluga carcass was found in the Tanana River near Fairbanks in central Alaska, nearly 1,700 km (1,100 mi) from the nearest ocean habitat. Belugas sometimes follow migrating fish, leading Alaska state biologist Tom Seaton to speculate it had followed migrating salmon up the river at some point in the previous autumn.[113] The rivers they most often travel up include: the Northern Dvina, the Mezen, the Pechora, the Ob and the Yenisei in Asia; the Yukon and the Kuskokwim in Alaska, and the Saint Lawrence in Canada.[105] Spending time in a river has been shown to stimulate an animal's metabolism and facilitates the seasonal renewal of the epidermal layer.[47] In addition, the rivers represent a safe haven for newborn calves where they will not be preyed upon by killer whales.[6] Calves often return to the same estuary as their mother in the summer, meeting her sometimes even after becoming fully mature.[114] However, not all beluga whale populations summer in estuaries. Belugas from the Beaufort Sea stock were found to summer along the Eastern Beaufort Sea shelf, Amundsen Gulf and slope regions north and west of Banks Island, in addition to core areas in the Mackenzie River Estuary. Male belugas have been observed summering in deeper waters along Viscount Melville Sound, in depths of up to 600 meters. The bulk of Eastern Chukchi Sea belugas summer over Barrow canyon.[115]

The migration season is relatively predictable, as it is basically determined by the amount of daylight and not by other variable physical or biological factors, such as the condition of the sea ice.[116] Vagrants may travel further south to areas such as Irish[117] and Scottish waters,[118] the islands of Orkney[119] and Hebrides,[120] and to Japanese waters.[121] There had been several vagrant individuals[122] that have demonstrated seasonal residencies at Volcano Bay,[123][124][125] and a unique whale were used to return annually to areas adjacent to Shibetsu in Nemuro Strait in the 2000s.[126] On rarer occasions, individuals of vagrancy can reach the Korean Peninsula.[127] A few other individuals have been confirmed to return to the coasts of Hokkaido, and one particular individual became a resident in brackish waters of Lake Notoro since in 2014.[128][129]

Some populations are not migratory and certain resident groups will stay in well-defined areas, such as in Cook Inlet, the estuary of the Saint Lawrence River and Cumberland Sound.[130] The population in Cook Inlet stays in the waters furthest inside the inlet during the summer until the end of autumn. Then during the winter, they disperse to the deeper water in the center of the inlet, but without completely leaving it.[131][132]

In April, the animals that spend the winter in the center and southwest of the Bering Sea move to the north coast of Alaska and the east coast of Russia.[130] The populations living in the Ungava Bay and the eastern and western sides of Hudson Bay overwinter together beneath the sea ice in Hudson Strait. Whales in James Bay that spend winter months within the basin, could be a distinct group from those in Hudson Bay.[133] The populations of the White Sea, the Kara Sea and the Laptev Sea overwinter in the Barents Sea.[130] In the spring, the groups separate and migrate to their respective summer sites.[130]

Habitat

Belugas exploit a varied range of habitats; they are most commonly seen in shallow waters close to the coast, but they have also been reported to live for extended periods in deeper water, where they feed and give birth to their young.[130]

In coastal areas, they can be found in coves, fjords, canals, bays and shallow waters in the Arctic Ocean that are continuously lit by sunlight.[33] They are also often seen during the summer in river estuaries, where they feed, socialize and give birth to young. These waters usually have a temperature between 8 and 10 °C.[33] The mudflats of Cook Inlet in Alaska are a popular location for these animals to spend the first few months of summer.[134] In the eastern Beaufort Sea, female belugas with their young and immature males prefer the open waters close to land, while the adult males live in waters covered by ice near the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. The younger males and females with slightly older young can be found nearer to the ice shelf.[135] Generally, the use of different habitats in summer reflects differences in feeding habits, risk from predators and reproductive factors for each of the subpopulations.[26]

Population

There are currently 22 stocks of beluga whales recognized: [136]

1. James Bay- 14,500 individuals (belugas remain here all year round) 2. Western Hudson Bay- 55,000 individuals 3. Eastern Hudson Bay- 3,400-3,800 individuals 4. Cumberland Sound- 1,151 individuals 5. Ungava Bay- 32 individuals (maybe functionally extinct) 6. St. Lawrence River Estuary- 889 individuals 7. Eastern Canadian Arctic- 21,400 individuals 8. Southwest Greenland- Extinct 9. Eastern Chukchi Sea- 20,700 individuals 10. Eastern Bering Sea- 7,000-9,200 individuals 11. Eastern Beaufort Sea- 39,300 individuals 12. Bristol Bay- 2,000-3,000 individuals 13. Cook Inlet- 300 individuals 14. White Sea- 5,600 individuals 15. Kara Sea/Laptev Sea/Barents Sea- Data Deficient 16. Ulbansky- 2,300 17. Anadyr- 3,000 18. Shelikhov- 2,666 19. Sakhalin/Amur- 4,000 individuals 20. Tugurskiy- 1,500 individuals 21. Udskaya- 2,500 individuals 22. Svalbard- 529 individuals

The Yakatat Bay belugas are not considered to be a true stock because they have only been present in these waters since the 1980s, and are believed to be of Cook Inlet origin. It is estimated that less than 20 whales inhabit the bay year-round. Overall the beluga population is estimated to be between 150,000-200,000 animals.

Threats

Hunting

The native populations of the Arctic in Alaska, Canada, Greenland and Russia hunt belugas, for both consumption and profit. Belugas have been easy prey for hunters due to their predictable migration patterns and the high population density in estuaries and surrounding coastal areas during the summer.[137]

Present

The number of animals killed is about 1,000 per year, (see table below. and its sources). Beluga whale hunting quotas in Canada and the United States are established using the Potential Biological Removal equation PBR = Nmin * 0.5 * Rmax * FR, to determine what constitutes a sustainable hunt. Nmin represents a conservative estimation of the population size, Rmax, represents the maximum rate of population increase and FR represents the recovery factor. [138]

Hunters in Hudson's Bay rarely eat the meat. They give a little to dogs, and leave the rest for wild animals.[139] Other areas may dry the meat for later consumption by humans. In Greenland the skin (muktuk) is sold commercially to fish factories,[140] and in Canada to other communities.[139] An average of one or two vertebrae and one or two teeth per beluga are carved and sold.[139] One estimate of the annual gross value received from Beluga hunts in Hudson Bay in 2013 was CA$600,000 for 190 belugas, or CA$3,000 per beluga. However, the net income, after subtracting costs in time and equipment, was a loss of CA$60 per person. Hunts receive subsidies, but they continue as a tradition, rather than for the money, and the economic analysis noted that whale watching may be an alternate revenue source. Of the gross income, CA$550,000 was for skin and meat, to replace beef, pork and chickens which would otherwise be bought. CA$50,000 was received for carved vertebrae and teeth.[139]

Russia now harvests 5 to 30 belugas per year for meat and captures an additional 20 to 30 per year for live export to Chinese aquaria.[141][142] However, in 2018, 100 were illegally captured for live export.[143][144]

Previous levels of commercial whaling have put the species in danger of extinction in areas such as Cook Inlet, Ungava Bay, the St. Lawrence River and western Greenland. Continued hunting by the native peoples may mean some populations will continue to decline.[145] Northern Canadian sites are the focus of discussions between local communities and the Canadian government, with the objective of permitting sustainable hunting that does not put the species at risk of extinction.[146]

The total amount of landed (defined as belugas successfully hunted and retrieved) belugas averages 275 in regard to the Bering, Chukchi and Beaufort stocks from 1987-2006. The average annual landed harvest of belugas in the Beaufort Sea consisted of 39 individuals while the Chukchi harvest averaged 62 individuals. Bristol bay’s annual average landed harvest was 17 while the Bering Sea’s was 152. Statistical studies have demonstrated that subsistence hunting in Alaska did not significantly impact the population of the Alaskan beluga whale stocks. The number of belugas struck and lost did not seem to profoundly impact Chukchi and Bering Sea belugas.[147]

Past

Commercial whaling by European, American and Russian whalers during the 18th and 19th centuries decreased beluga populations in the Arctic.[137][148][149] The animals were hunted for their meat and blubber, while the Europeans used the oil from the melon as a lubricant for clocks, machinery and lighting in lighthouses.[137] Mineral oil replaced whale oil in the 1860s, but the hunting of these animals continued unabated. In 1863, the cured skin could be used to make horse harnesses, machine belts for saw mills and shoelaces. These manufactured items ensured the hunting of belugas continued for the rest of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century.[150] The cured skin is the only cetacean skin that is sufficiently thick to be used as leather.[137] In fact, their skin is so thick, that it was even used to manufacture some of the first bulletproof vests.[151]

Russia had large hunts, peaking in the 1930s at 4,000 per year and the 1960s at 7,000 per year, for a total of 86,000 from 1915 to 2014.[141][148] Canada hunted a total of 54,000 from 1731 to 1970.[152] Between 1868 and 1911, Scottish and American whalers killed more than 20,000 belugas in Lancaster Sound and Davis Strait.[137]

During the 1920s, fishermen in the Saint Lawrence River estuary considered belugas to be a threat to the fishing industry, as they eat large quantities of cod, salmon, tuna and other fish caught by the local fishermen.[150] The presence of belugas in the estuary was, therefore, considered to be undesirable; in 1928, the Government of Quebec offered a reward of 15 dollars for each dead beluga.[153] The Quebec Department of Fisheries launched a study into the influence of these cetaceans on local fish populations in 1938. The unrestricted killing of belugas continued into the 1950s, when the supposed voracity of the belugas was found to be overestimated and did not adversely affect fish populations.[150] L'Isle-aux-Coudres is the setting for the classic 1963 National Film Board of Canada documentary Pour la suite du monde, which depicts a one-off resurrection of the beluga hunt; one animal is caught live, and transported by truck to an aquarium in the big city. The method of capture is akin to dolphin drive hunting.

Beluga catches by location

| Beaufort Sea, Mackenzie, Paulatuk, Ulukhaktok, Canada | Nunavut, Canada | Nunavik, Quebec, Canada | Western Arctic, Russia, hunted for meat | Eastern Arctic, Russia, hunted for meat | Sea of Okhotsk, Russia, hunted for meat | All areas of Russia, live export | Year | Canada total | Greenland | USSR+ Russia total | USA (Alaska) | World total, incomplete | Lost at sea as % of caught |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 157 | 2016 | 157 | 246 | ||||||||||

| 83 | 303 | 2015 | 386 | 156 | 326 | 868 | |||||||

| 136 | 302 | 30 | 23 | 2014 | 438 | 317 | 53 | 346 | 1154 | 2% | |||

| 92 | 207 | 30 | 23 | 2013 | 299 | 353 | 53 | 367 | 1072 | 2% | |||

| 102 | 207 | 30 | 44 | 2012 | 309 | 245 | 74 | 360 | 988 | 4% | |||

| 72 | 207 | 30 | 33 | 2011 | 279 | 179 | 63 | 288 | 809 | 3% | |||

| 94 | 207 | 30 | 30 | 2010 | 301 | 222 | 60 | 318 | 901 | 3% | |||

| 102 | 207 | 30 | 24 | 2009 | 309 | 286 | 54 | 253 | 902 | 6% | |||

| 79 | 207 | 30 | 25 | 2008 | 286 | 330 | 55 | 254 | 925 | 8% | |||

| 85 | 207 | 30 | 0 | 2007 | 292 | 145 | 30 | 576 | 1043 | 2% | |||

| 126 | 207 | 30 | 20 | 2006 | 333 | 169 | 50 | 226 | 778 | 3% | |||

| 108 | 207 | 30 | 31 | 2005 | 315 | 231 | 61 | 282 | 889 | 2% | |||

| 142 | 207 | 30 | 25 | 2004 | 349 | 246 | 55 | 234 | 884 | 8% | |||

| 125 | 250 | 207 | 30 | 26 | 2003 | 582 | 510 | 56 | 251 | 1399 | 9% | ||

| 89 | 170 | 210 | 30 | 10 | 2002 | 469 | 510 | 40 | 362 | 1381 | 3% | ||

| 96 | 370 | 30 | 22 | 2001 | 466 | 560 | 52 | 416 | 1494 | 1% | |||

| 91 | 116 | 243 | 30 | 10 | 2000 | 450 | 733 | 40 | 280 | 1503 | 8% | ||

| 102 | 207 | 243 | 30 | 23 | 1999 | 552 | 590 | 53 | 217 | 1412 | 19% | ||

| 93 | 137 | 243 | 30 | 23 | 1998 | 473 | 873 | 53 | 342 | 1741 | 8% | ||

| 123 | 376 | 243 | 30 | 23 | 1997 | 742 | 682 | 53 | 276 | 1753 | 8% | ||

| 139 | 203 | 243 | 30 | 23 | 1996 | 585 | 681 | 53 | 389 | 1708 | 16% | ||

| 143 | 30 | 23 | 1995 | 143 | 960 | 53 | 171 | 1327 | 11% | ||||

| 149 | 30 | 23 | 1994 | 149 | 757 | 53 | 285 | 1244 | 6% | ||||

| 120 | 30 | 23 | 1993 | 120 | 930 | 53 | 369 | 1472 | 9% | ||||

| 130 | 30 | 23 | 1992 | 130 | 1014 | 53 | 181 | 1378 | 7% | ||||

| 144 | 30 | 23 | 1991 | 144 | 747 | 53 | 315 | 1259 | 24% | ||||

| 106 | 30 | 23 | 1990 | 106 | 933 | 53 | 335 | 1427 | 22% | ||||

| 156 | 27 | 30 | 23 | 1989 | 156 | 816 | 80 | 13 | 1065 | 15% | |||

| 139 | 7 | 30 | 23 | 1988 | 139 | 428 | 60 | 19 | 646 | 19% | |||

| 174 | 15 | 30 | 23 | 1987 | 174 | 928 | 68 | 22 | 1192 | 13% | |||

| 199 | 192 | 30 | 23 | 1986 | 199 | 973 | 245 | 0 | 1417 | 15% | |||

| 148 | 248 | 150 | 30 | 1985 | 148 | 887 | 428 | 0 | 1463 | 17% | |||

| 156 | 850 | 150 | 30 | 1984 | 156 | 930 | 1030 | 170 | 2286 | 20% | |||

| 102 | 450 | 150 | 30 | 1983 | 102 | 888 | 630 | 235 | 1855 | 20% | |||

| 146 | 116 | 150 | 30 | 1982 | 146 | 1217 | 296 | 335 | 1994 | 19% | |||

| 155 | 294 | 150 | 30 | 1981 | 155 | 1506 | 474 | 209 | 2344 | 20% | |||

| 85 | 368 | 150 | 30 | 1980 | 85 | 1346 | 548 | 249 | 2228 | 23% | |||

| 171 | 200 | 26 | 30 | 1979 | 171 | 1116 | 256 | 138 | 1681 | 22% | |||

| 157 | 63 | 26 | 30 | 1978 | 157 | 1112 | 119 | 177 | 1565 | 25% | |||

| 172 | 1196 | 26 | 30 | 1977 | 172 | 1264 | 1252 | 247 | 2935 | 22% | |||

| 183 | 472 | 26 | 30 | 1976 | 183 | 1260 | 528 | 186 | 2157 | 28% | |||

| 177 | 169 | 23 | 30 | 1975 | 177 | 995 | 222 | 185 | 1579 | 23% | |||

| 152 | 194 | 23 | 30 | 1974 | 152 | 1149 | 247 | 184 | 1732 | 25% | |||

| 212 | 288 | 23 | 30 | 1973 | 212 | 1451 | 341 | 150 | 2154 | 23% | |||

| 134 | 288 | 30 | 1972 | 134 | 1168 | 318 | 180 | 1800 | 21% | ||||

| 94 | 612 | 30 | 1971 | 94 | 913 | 642 | 250 | 1899 | 23% | ||||

| 137 | 990 | 30 | 1970 | 137 | 861 | 1020 | 200 | 2218 | 25% | ||||

| 302 | 700 | 30 | 1969 | 0 | 1364 | 1032 | 170 | 2566 | 25% | ||||

| 14 | 30 | 700 | 30 | 1968 | 14 | 1490 | 760 | 150 | 2414 | 26% | |||

| 40 | 274 | 700 | 30 | 1967 | 40 | 825 | 1004 | 225 | 2094 | 24% | |||

| 96 | 3046 | 700 | 30 | 1966 | 96 | 828 | 3776 | 225 | 4925 | 23% | |||

| 70 | 3614 | 700 | 30 | 1965 | 70 | 595 | 4344 | 225 | 5234 | 21% | |||

| 45 | 5952 | 700 | 30 | 1964 | 45 | 403 | 6682 | 225 | 7355 | 22% | |||

| 94 | 2526 | 700 | 30 | 1963 | 94 | 278 | 3256 | 225 | 3853 | 21% | |||

| 96 | 2334 | 700 | 30 | 1962 | 96 | 409 | 3064 | 225 | 3794 | 24% | |||

| 145 | 3500 | 700 | 30 | 1961 | 145 | 438 | 4230 | 300 | 5113 | 27% | |||

| 145 | 6444 | 700 | 30 | 1960 | 145 | 398 | 7174 | 375 | 8092 | 22% | |||

| 1945 | 700 | 830 | 1959 | 472 | 3475 | 450 | 4397 | 24% | |||||

| 2103 | 700 | 830 | 1958 | 411 | 3633 | 450 | 4494 | 23% | |||||

| 796 | 700 | 830 | 1957 | 770 | 2326 | 450 | 3546 | 26% | |||||

| 600 | 700 | 830 | 1956 | 671 | 2130 | 450 | 3251 | 25% | |||||

| 329 | 700 | 130 | 1955 | 507 | 1159 | 450 | 2116 | 24% | |||||

| 776 | 700 | 130 | 1954 | 767 | 1606 | 450 | 2823 | 28% | |||||

| 1960–1969[149] 1970–99[154] 2000–2012[155] 2013–15[156] 2014[157] | Arviat[158] | 1996–2002[159]

2003–16[160] |

1954–99[148] | 1954–1985 cites Russian papers[149] | NMFS cites Russian paper[141] | Western[148] Okhotsk[141] | Sources | Total of columns at left, incomplete | 1954–2016[161] | Total of columns at left, incomplete | 1954–84[149] 1987–90 Cook Inlet[162] 1990–2011[163] 2012–2015 +Cook Inlet[164][165] | Total of other columns | Greenland source 1954–1999, Beaufort source 2000–2012 |

Predation

During the winter, belugas commonly become trapped in the ice without being able to escape to open water, which may be several kilometres away.[166] Polar bears take particular advantage of these situations and are able to locate the belugas using their sense of smell. The bears swipe at the belugas and drag them onto the ice to eat them.[28] They are able to capture large individuals in this way; in one documented incident, a bear weighing between 150 and 180 kg was able to capture an animal that weighed 935 kg.[167]

Killer whales are able to capture both young and adult belugas.[28] They live in all the seas of the world and share the same habitat as belugas in the sub-Arctic region. Attacks on belugas by killer whales have been reported in the waters of Greenland, Russia, Canada and Alaska.[168][169] A number of killings have been recorded in Cook Inlet, and experts are concerned the predation by killer whales will impede the recovery of this sub-population, which has already been badly depleted by hunting.[168] The killer whales arrive at the beginning of August, but the belugas are occasionally able to hear their presence and evade them. The groups near to or under the sea ice have a degree of protection, as the killer whale's large dorsal fin, up to 2 m in length, impedes their movement under the ice and does not allow them to get sufficiently close to the breathing holes in the ice.[33] Beluga whale behavior under killer whale predation makes them vulnerable to hunters. When killer whales are present, large numbers of beluga whales congregate in the shallows for protection, which allows them to be hunted in droves.

Contamination

The beluga is considered an excellent sentinel species (indicator of environment health and changes), because it is long-lived, at the top of the food web, bears large amounts of fat and blubber, relatively well-studied for a cetacean, and still somewhat common.

Human pollution can be a threat to belugas' health when they congregate in river estuaries. Chemical substances such as DDT and heavy metals such as lead, mercury and cadmium have been found in individuals of the Saint Lawrence River population.[170] Local beluga carcasses contain so many contaminants, they are treated as toxic waste.[171] Levels of polychlorinated biphenyls between 240 and 800 ppm have been found in belugas' brains, liver and muscles, with the highest levels found in males.[172] These levels are significantly greater than those found in Arctic populations.[173] These substances have a proven adverse effect on these cetaceans, as they cause cancers, reproductive diseases and the deterioration of the immune system, making individuals more susceptible to pneumonias, ulcers, cysts, tumours and bacterial infections.[173] Although the populations that inhabit the river estuaries run the greatest risk of contamination, high levels of zinc, cadmium, mercury and selenium have also been found in the muscles, livers and kidneys of animals that live in the open sea.[174]Mercury is a particular area of concern. The concentration of Mercury in Beaufort Sea belugas tripled from the 1980’s to the 1990’s. However, mercury concentration has decreased in Beaufort belugas as of the 21st century, possibly due to changes in dietary preference. Larger body sized belugas tend to have more mercury than smaller sized belugas, because they spend more time offshore, hunting prey such as cod and shrimp, which have more mercury.[175]

From a sample of 129 beluga adults from the Saint Lawrence River examined between 1983 and 1999, a total of 27% had suffered cancer.[176] This is a higher percentage than that documented for other populations of this species and is much higher than for other cetaceans and for the majority of terrestrial mammals; in fact, the rate is only comparable to the levels found in humans and some domesticated animals.[176] For example, the rate of intestinal cancer in the sample is much higher than for humans. This condition is thought to be directly related to environmental contamination, in this case by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, and coincides with the high incidence of this disease in humans residing in the area.[176] The prevalence of tumours suggests the contaminants identified in the animals that inhabit the estuary are having a direct carcinogenic effect or they are at least causing an immunological deterioration that is reducing the inhabitants' resistance to the disease.[177]

Indirect human disturbance may also be a threat. While some populations tolerate small boats, most actively try to avoid ships. Whale-watching has become a booming activity in the St. Lawrence and Churchill River areas, and acoustic contamination from this activity appears to have an effect on belugas. For example, a correlation appears to exist between the passage of belugas across the mouth of the Saguenay River, which has decreased by 60%, and the increase in the use of recreational motorboats in the area.[178] A dramatic decrease has also been recorded in the number of calls between animals (decreasing from 3.4 to 10.5 calls/min to 0 or <1) after exposure to the noise produced by ships, the effect being most persistent and pronounced with larger ships such as ferries than with smaller boats.[179] Belugas can detect the presence of large ships (for example icebreakers) up to 50 km away, and they move rapidly in the opposite direction or perpendicular to the ship following the edge of the sea ice for distances of up to 80 km to avoid them. The presence of shipping produces avoidance behaviour, causing deeper dives for feeding, the break-up of groups, and asynchrony in dives.[180]

Pathogens

As with any animal population, a number of pathogens cause death and disease in belugas, including viruses, bacteria, protozoans and fungi, which mainly cause skin, intestinal and respiratory infections.[181]

Papillomaviruses have been found in the stomachs of belugas in the Saint Lawrence River. Animals in this location have also been recorded as suffering infections caused by herpesviruses and in certain cases to be suffering from encephalitis caused by the protozoan Sarcocystis. Cases have been recorded of ciliate protozoa colonising the spiracle of certain individuals, but they are not thought to be pathogens or are not very harmful.[182]:26, 303, 359

The bacterium Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, which probably comes from eating infected fish, poses a threat to belugas kept in captivity, causing anorexia and dermal plaques and lesions that can lead to sepsis.[182]:26, 303, 359 This condition can cause death if it is not diagnosed and treated in time with antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin.[183][182][182]:316–7

A study of infections caused by parasitic worms in a number of individuals of both sexes found the presence of larvae from a species from the genus Contracaecum in their stomachs and intestines, Anisakis simplex in their stomachs, Pharurus pallasii in their ear canals, Hadwenius seymouri in their intestines and Leucasiella arctica in their rectums.[184]

Relationship with humans

Captivity

Belugas were among the first whale species to be kept in captivity. The first beluga was shown at Barnum's Museum in New York City in 1861.[185] For most of the 20th century, Canada was the predominant source for belugas destined for exhibition. Throughout the early 1960s, belugas were taken from the St. Lawrence River estuary. In 1967, the Churchill River estuary became the main source from which belugas were captured. This continued until 1992, when the practice was banned.[152] Since Canada ceased to be the supplier of these animals, Russia has become the largest provider.[152] Individuals are caught in the Amur River delta and the far eastern seas of the country, and then are either transported domestically to aquaria in Moscow, St. Petersburg and Sochi, or exported to foreign nations, including China[142] and formerly Canada.[152] Canada has now banned the practice of holding new animals in captivity.[186]

To provide some enrichment while in captivity, aquaria train belugas to perform behaviours for the public[187] and for medical exams, such as blood draws,[188] ultrasound,[189] providing toys,[187] and allowing the public to play recorded or live music.[190]

Between 1960 and 1992, the United States Navy carried out a program that included the study of marine mammals' abilities with echolocation, with the objective of improving the detection of underwater objects. The program started with dolphins, but a large number of belugas were also used from 1975 onwards. The program included training these mammals to carry equipment and material to divers working under water, the location of lost objects, surveillance of ships and submarines, and underwater monitoring using cameras held in their mouths. A similar program was implemented by the Soviet Navy during the Cold War, in which belugas were also trained for antimining operations in Arctic waters.[170] It is possible this program continues within the Russian Navy, as on April 24, 2019 a tame beluga whale wearing a Russian equipment harness was found by fishermen near the Norwegian island of Ingøya.[192]

Belugas released from captivity have difficulties adapting to life in the wild, but if not fed by humans they may have a chance to join a group of wild belugas and learn to feed themselves, according to Audun Rikardsen of the University of Tromsø.[193]

In 2019, a sanctuary in Iceland was established for belugas that retired from a marine park in China. A British company, Merlin Entertainments, bought the park in 2012, as part of an Australian chain, and it is one of their largest aquaria.[194] Merlin has a policy against captive cetaceans, so they sponsored a 32,000-square-metre sea pen as a sanctuary. The 12-year-old belugas, caught in Russia and raised in captivity, do not know how to live in the wild.[195][196] The cost is variously listed as ISK 3,000,000 (US$24,000) or US$27,000,000.[195] Merlin was owned until 2015 by Blackstone Group, which also owned SeaWorld[197] until selling its last stake in 2017 to a Chinese company which will use SeaWorld's expertise to expand in China;[198] SeaWorld still keeps belugas in captivity.

Belugas are the only whale species kept in aquaria and marine parks. They are displayed across North America, Europe and Asia.[152] As of 2006, 58 belugas were held in captivity in Canada and the United States, and 42 deaths in US captivity had been reported up to that time. A single specimen costs up to US$100,000, although the price has now dropped to US$70,000.[199][152] As of January 2018, according to the nonprofit Ceta Base, which tracks belugas and dolphins under human care, there were 81 captive belugas in Canada and the United States, and unknown numbers in the rest of the world.[200][199][201] The beluga's popularity with visitors reflects its attractive colour and its range of facial expressions. The latter is possible because while most cetacean "smiles" are fixed, the extra movement afforded by the beluga's unfused cervical vertebrae allows a greater range of apparent expression.[43]

Most belugas found in aquaria are caught in the wild, as captive-breeding programs have not had much success so far.[202] For example, despite best efforts, as of 2010, only two male whales had been successfully used as stud animals in the Association of Zoos and Aquariums beluga population, Nanuq at SeaWorld San Diego and Naluark at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, USA. Nanuq has fathered 10 calves, five of which survived birth.[203] Naluark at Shedd Aquarium has fathered four living offspring.[204] Naluark was relocated to the Mystic Aquarium in the hope that he would breed with two of their females,[205] but he did not, and in 2016 he was moved to SeaWorld Orlando.[206] The first beluga calf born in captivity in Europe was born in L'Oceanogràfic marine park in Valencia, Spain, in November 2006.[207] However, the calf died 25 days later after suffering metabolic complications, infections and not being able to feed properly.[208] A second calf was born on 16 November 2016, and was successfully maintained by artificial feeding based on enriched milk.[209]

In 2009 during a free-diving competition in a tank of icy water in Harbin, China, a captive beluga brought a cramp-paralysed diver from the bottom of the pool up to the surface by holding her foot in its mouth, saving the diver's life.[210][211]

Films which have publicised issues of beluga welfare include Born to Be Free,[212] Sonic Sea,[213] and Vancouver Aquarium Uncovered.[214]

Whale watching

Whale watching has become an important activity in the recovery of the economies of towns in Quebec and Hudson Bay, near the Saint Lawrence and Churchill Rivers (in fact Churchill is considered to be the Beluga Whale Capital of the World) [215]respectively. The best time to see belugas is during the summer, when they meet in large numbers in the estuaries of the rivers and in their summer habitats.[216] The animals are easily seen due to their high numbers and their curiosity regarding the presence of humans.[216]

However, the boats' presence poses a threat to the animals, as it distracts them from important activities such as feeding, social interaction and reproduction. In addition, the noise produced by the motors has an adverse effect on their auditory function and reduces their ability to detect their prey, communicate and navigate.[217] To protect these marine animals during whale-watching activities, the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has published a "Guide for observing marine life". The guide recommends boats carrying the whale watchers keep their distance from the cetaceans and it expressly prohibits chasing, harassing, obstructing, touching, or feeding them.[218]

Some regular migrations do occur into Russian EEZ of Sea of Japan such as to Rudnaya Bay, where diving with wild belugas became a less-known but popular attraction.[219]

On 25 September 2018, a beluga was sighted in the Thames Estuary and near towns along the Kent side of the Thames, being nicknamed Benny by newspapers. The whale, who was noticed by conservationists to be travelling alone, appeared to be separated from the rest of its group, and is thought to be a lost individual. Subsequent sightings were reported on the following day,[220] and continued into 2019, when local experts concluded that Benny had left the estuary.[221]

Human speech

Male belugas in captivity can mimic the pattern of human speech, several octaves lower than typical whale calls. It is not the first time a beluga has been known to sound human, and they often shout like children, in the wild.[222] One captive beluga, after overhearing divers using an underwater communication system, caused one of the divers to surface by imitating their order to get out of the water. Subsequent recordings confirmed that the beluga had become skilled at imitating the patterns and frequency of human speech. After several years, this beluga ceased making these sounds.[223]

Conservation status

.jpg)

Prior to 2008, the beluga was listed as "vulnerable" by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), a higher level of concern. The IUCN cited the stability of the largest sub-populations and improved census methods that indicate a larger population than previously estimated. In 2008, the beluga was reclassified as "near threatened" by the IUCN due to uncertainty about threats to their numbers and the number of belugas over parts of its range (especially the Russian Arctic), and the expectation that if current conservation efforts cease, especially hunting management, the beluga population is likely to qualify for "threatened" status within five years.[224] In June 2017, its status was reassessed to "least concern".[2]

There are about 21 sub-populations of beluga whales and it is estimated that 200,000 individuals still exist, which are listed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List.[225] However, the nonmigratory Cook Inlet sub-population off the Gulf of Alaska is a separate sub-population that is listed as "critically endangered" by the IUCN as of 2006[2] and as "endangered" under the Endangered Species Act as of October 2008.[226][227][228][2] This was primarily due to unregulated overharvesting of beluga whales prior to 1998. The population has remained relatively consistent, though the reported harvest has been small. As of 2016, the estimated abundance of the endangered Cook Inlet population was 293 individuals. [229] The most recent estimate in 2018 by NOAA Fisheries suggested that the population declined to 279 individuals. [229]

Despite beluga whales not being threatened overall, sub-populations are being listed as critically endangered and are facing increased mortality from human actions. For example, even though commercial hunting is now banned due to the Marine Mammal Protection Act, beluga whales are still being hunted to preserve the livelihood of native Alaskan communities.[230] The IUCN and NOAA Fisheries cite habitat degradation, oil and gas drilling, underwater noise, harvesting for consumption and climate change as threats to the prolonged survival of beluga whale sub-populations.[231]

Beluga whale populations are currently being harvested at levels which are not sustainable and it is difficult for those harvesting beluga whales to know which sub-population they are from.[232] Because there is little protection of sub-populations, harvest will need to be managed to ensure sub-populations will survive long into the future to discover the importance of their migratory patterns and habitat use.

Beluga whales, like most other arctic species, are being faced with alteration of their habitat due to climate change and melting arctic ice.[232] Changes in sea-ice has resulted in changes in the area used by Chukchi belugas, since belugas spent less time in close proximity to the ice edge in comparison to previous years. Additionally, Chukchi Sea belugas spent a prolonged amount of time in Barrow Canyon on the Beaufort Sea side in October. Chukchi sea belugas also appear to be spending more time in deeper water presently, as opposed to the 1990’s. Belugas also seemed to be taking longer and deeper dives. A hypothesis as to why this might be the case is an up-welling of rich Atlantic water in the Beaufort Sea may result in concentrated prey items like Arctic cod. The fall migration of Chukchi belugas is later, although summer and fall habitat selection has not changed. Fall migration of Chukchi belugas appears to be correlated with Beaufort Sea freeze up.[233]

It is hypothesized that beluga whales utilize ice as protection from killer whale predation or for feeding on schools of fish.[234] Killer whales can penetrate further into the Arctic and remain in arctic waters for a longer period of time due to reductions in sea ice. For example, residents in Kotzebue, have reported that killer whales have been sighted more frequently in Kotzebue Sound.

As annual ice cover declines, humans may gain access and disrupt beluga whale habitats.[234] For example, the number of vessels in the Arctic for gas and oil exploration, fishing, and commercial shipping has already increased and a continuous trend may lead to higher risks of injuries and deaths for beluga whales.[234]

In addition, it is possible that beluga whales may face by an increased risk of entrapment from leads and cracks freezing, due to the erratic nature of climate change. Abrupt changes in weather can cause these leads and cracks to freeze ultimately causing the whales to die of suffocation.[232] An increase in urbanization will likely lead to higher concentrations of toxic pollutants in the blubber of beluga whales since they are at the top of the food chain and are affected by bio-accumulation.[234] Loss of sea ice and a change in ocean temperatures may also affect the distribution and composition of prey or affect their competition.[234] There is also some evidence that climate change can affect males and females differently. Since 1983, belugas have been increasing scarce in Kotzebue sound. However, in 2007, several hundred whales were spotted in the sound, with over 90% of the whales being male. However, more research needs to be conducted to understand how climate change affects beluga whale sex aggregation. [235]

Legal protection

The US Congress passed the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972, outlawing the persecution and hunting of all marine mammals within US coastal waters. The act has been amended a number of times to permit subsistence hunting by native peoples, temporary capture of restricted numbers for research, education and public display, and to decriminalise the accidental capture of individuals during fishing operations.[236] The act also states that all whales in US territorial waters are under the jurisdiction of the National Marine Fisheries Service, a division of NOAA.[236]

To prevent hunting, belugas are protected under the 1986 International Moratorium on Commercial Whaling; however, hunting of small numbers of belugas is still allowed. Since it is very difficult to know the exact population of belugas because their habitats include inland waters away from the ocean, they easily come in contact with oil and gas development centres. To prevent whales from coming in contact with industrial waste, the Alaskan and Canadian governments are relocating sites where whales and waste come in contact.

The beluga whale is listed on appendix II[237] of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS). It is listed on appendix II[237] as it has an unfavourable conservation status or would benefit significantly from international co-operation organised by tailored agreements. All toothed whales are protected under the CITES that was signed in 1973 to regulate the commercial exploitation of certain species.[238]

The isolated beluga population in the Saint Lawrence River has been legally protected since 1983.[239] In 1988 Canadian Department of Fisheries and Oceans and Environment Canada, a governmental agency that supervises national parks, implemented the Saint Lawrence Action Plan[240] with the aim of reducing industrial contamination by 90% by 1993; as of 1992, the emissions had been reduced by 59%.[145] The population of the St. Lawrence belugas decreased from 10,000 in 1885 to around 1,000 in the 1980 and around 900 in 2012.[241]

Conservation research in managed care facilities

As of 2015, there were 33 individuals housed in managed care facilities in North America.[242] These facilities are members of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums, aiming to understand the complex reproductive physiology of this species to improve their conservation. With the extreme difficulty of studying beluga whales in the wild and the lack of ability to collect biological samples or perform examinations on individuals, managed care facilities play a critical role.[243]

Managed care facilities in North America have been able to work cooperatively to build upon the research of beluga whale reproduction and have made remarkable advances. Using operant conditioning, these facilities have trained beluga whales for voluntary biological sampling and examinations. Blood[244], urine[245], and blow samples[246] have all been collected for longitudinal hormone monitoring studies.

In addition, beluga whales have undergone semen collection[242], body temperature data collection[244], reproductive tract examinations via transabdominal ultrasound, and endoscopic exams.[247] With new technology, the reproductive characteristics of both the female and male beluga whale have been accurately described and has benefited captive breeding programs globally.

As more research is done, the management of beluga whales in managed care facilities can be greatly improved and may even help develop other cetacean breeding and contraceptive programs, such as that of the bottlenose dolphin.[242] Through fetal health and gestation monitoring, facilities can be more equipped to deal with pregnant animals as well.[244] While training has been done to collect beluga whale semen, only few facilities have been able to successfully do so as both saltwater and urine contamination need to be avoided.[248] Improvement of this process will help increase the success of captive breeding programs.

Cultural references

Pour la suite du monde, is a Canadian documentary film released in 1963 about traditional beluga hunting carried out by the inhabitants of L'Isle-aux-Coudres on the Saint Lawrence River.[249]

The children's singer Raffi released an album called Baby Beluga in 1980. The album starts with the sound of whales communicating, and includes songs representing the ocean and whales playing. The song "Baby Beluga" was composed after Raffi saw a recently born beluga calf in Vancouver Aquarium.[250]

The fuselage design of the Airbus Beluga, one of the world's biggest cargo planes, is very similar to that of a beluga. It was originally called the Super Transporter, but the nickname Beluga became more popular and was then officially adopted.[251] The company paints the 2019 Beluga XL version to emphasize the plane's similarity to the Beluga whale.[252]

.jpg)

In the 2016 Disney/Pixar animated film Finding Dory, the sequel to Finding Nemo (2003), the character Bailey is a beluga whale, and its echolocation abilities are a significant part of the plot.[253] [254]

See also

References

- Mead, J.G.; Brownell, R. L. Jr. (2005). "Order Cetacea". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 735. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- Lowry, L (2017). "Delphinapterus leucas". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2017. Retrieved 21 December 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bradford, Alina; July 19, Live Science Contributor |; ET, 2016 08:45pm. "Facts About Beluga Whales". Live Science. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- Arnold, P. "Irrawaddy Dolphin Orcaella brevirostris". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. p. 652.

- Grétarsdóttir, S.; Árnason, Ú. (1992). "Evolution of the common cetacean highly repetitive DNA component and the systematic position of Orcaella brevirostris". Journal of Molecular Evolution. 34 (3): 201–208. Bibcode:1992JMolE..34..201G. doi:10.1007/BF00162969. PMID 1588595.

- O'Corry-Crowe, G. "Beluga Whale Delphinapterus leucas". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. pp. 94–99.

- Heide-Jørgensen, Mads P.; Reeves, Randall R. (1993). "Description of an Anomalous Monodontid Skull from West Greenland: A Possible Hybrid?". Marine Mammal Science. 9 (3): 258–68. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.1993.tb00454.x.

- Leatherwood, Stephen; Reeves, Randall R. (1983). The Sierra Club Handbook of Whales and Dolphins. Sierra Club Books. p. 320. ISBN 978-0-87156-340-8.

- "Japanese whale whisperer teaches beluga to talk". meeja.com.au. 16 September 2008. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 16 September 2008.

- Kusma, Stephanie (23 October 2012). "Ein "sprechender" Beluga-Wal" [A "talking" Beluga whale]. Neue Zürcher Zeitung (in German). Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 25 October 2012.