Tree line

The tree line is the edge of the habitat at which trees are capable of growing. It is found at high elevations and high latitudes. Beyond the tree line, trees cannot tolerate the environmental conditions (usually cold temperatures or associated lack of available moisture).[1]:51 The tree line is sometimes distinguished from a lower timberline or forest line, which is the line below which trees form a forest with a closed canopy.[2]:151[3]:18

At the tree line, tree growth is often sparse, stunted, and deformed by wind and cold. This is sometimes known as krummholz (German for "crooked wood").[4]:58

The tree line often appears well-defined, but it can be a more gradual transition. Trees grow shorter and often at lower densities as they approach the tree line, above which they cease to exist.[4]:55

Types

Several types of tree lines are defined in ecology and geography:

Alpine

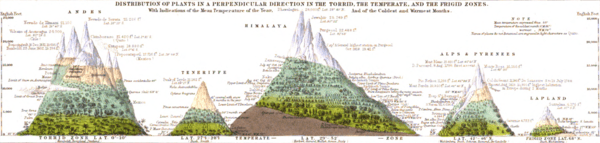

An alpine tree line is the highest elevation that sustains trees; higher up it is too cold, or the snow cover lasts for too much of the year, to sustain trees.[2]:151 The climate above the tree line of mountains is called an alpine climate,[5]:21 and the terrain can be described as alpine tundra.[6] Treelines on north-facing slopes in the northern hemisphere are lower than on south-facing slopes, because the increased shade on north-facing slopes means the snowpack takes longer to melt. This shortens the growing season for trees.[7]:109 In the southern hemisphere, the south-facing slopes have the shorter growing season.

The alpine tree line boundary is seldom abrupt: it usually forms a transition zone between closed forest below and treeless alpine tundra above. This zone of transition occurs "near the top of the tallest peaks in the northeastern United States, high up on the giant volcanoes in central Mexico, and on mountains in each of the 11 western states and throughout much of Canada and Alaska".[8] Environmentally dwarfed shrubs (krummholz) commonly form the upper limit.

The decrease in air temperature with increasing elevation creates the alpine climate. The rate of decrease can vary in different mountain chains, from 3.5 °F (1.9 °C) per 1,000 feet (300 m) of elevation gain in the dry mountains of the western United States,[8] to 1.4 °F (0.78 °C) per 1,000 feet (300 m) in the moister mountains of the eastern United States.[9] Skin effects and topography can create microclimates that alter the general cooling trend.[10]

Compared with arctic timberlines, alpine timberlines may receive fewer than half of the number of degree days (above 10 °C (50 °F)) based on air temperature, but because solar radiation intensities are greater at alpine than at arctic timberlines the number of degree days calculated from leaf temperatures may be very similar.[8]

Summer warmth generally sets the limit to which tree growth can occur, for while timberline conifers are very frost-hardy during most of the year, they become sensitive to just 1 or 2 degrees of frost in mid-summer.[11][12] A series of warm summers in the 1940s seems to have permitted the establishment of "significant numbers" of spruce seedlings above the previous treeline in the hills near Fairbanks, Alaska.[13][14] Survival depends on a sufficiency of new growth to support the tree. The windiness of high-elevation sites is also a potent determinant of the distribution of tree growth. Wind can mechanically damage tree tissues directly, including blasting with windborne particles, and may also contribute to the desiccation of foliage, especially of shoots that project above snow cover.

At the alpine timberline, tree growth is inhibited when excessive snow lingers and shortens the growing season to the point where new growth would not have time to harden before the onset of fall frost. Moderate snowpack, however, may promote tree growth by insulating the trees from extreme cold during the winter, curtailing water loss,[15] and prolonging a supply of moisture through the early part of the growing season. However, snow accumulation in sheltered gullies in the Selkirk Mountains of southeastern British Columbia causes the timberline to be 400 metres (1,300 ft) lower than on exposed intervening shoulders.[16]

Desert

In a desert, the tree line marks the driest places where trees can grow; drier desert areas having insufficient rainfall to sustain them. These tend to be called the "lower" tree line, and occur below about 5,000 ft (1,500 m) elevation in the desert of the southwestern United States.[17] The desert tree line tends to be lower on pole-facing slopes than equator-facing slopes, because the increased shade on the former keeps them cooler and prevents moisture from evaporating as quickly, giving trees a longer growing season and more access to water.

Desert-alpine

In some mountainous areas, higher elevations above the condensation line, or on equator-facing and leeward slopes, can result in low rainfall and increased exposure to solar radiation. This dries out the soil, resulting in a localized arid environment unsuitable for trees. Many south-facing ridges of the mountains of the Western U.S. have a lower treeline than the northern faces because of increased sun exposure and aridity.

Double tree line

Different tree species have different tolerances to drought and cold. Mountain ranges isolated by oceans or deserts may have restricted repertoires of tree species with gaps that are above the alpine tree line for some species yet below the desert tree line for others. For example, several mountain ranges in the Great Basin of North America have lower belts of pinyon pines and junipers separated by intermediate brushy but treeless zones from upper belts of limber and bristlecone pines.[18]:37

Exposure

On coasts and isolated mountains the tree line is often much lower than in corresponding altitudes inland and in larger, more complex mountain systems, because strong winds reduce tree growth. In addition the lack of suitable soil, such as along talus slopes or exposed rock formations, prevents trees from gaining an adequate foothold and exposes them to drought and sun.

Arctic

The arctic tree line is the northernmost latitude in the Northern Hemisphere where trees can grow; farther north, it is too cold all year round to sustain trees.[19] Extremely cold temperatures, especially when prolonged, can freeze the internal sap of trees, killing them. In addition, permafrost in the soil can prevent trees from getting their roots deep enough for the necessary structural support.

Unlike alpine timberlines, the northern timberline occurs at low elevations. The arctic forest–tundra transition zone in northwestern Canada varies in width, perhaps averaging 145 kilometres (90 mi) and widening markedly from west to east,[20] in contrast with the telescoped alpine timberlines.[8] North of the arctic timberline lies the low-growing tundra, and southwards lies the boreal forest.

Two zones can be distinguished in the arctic timberline:[21][22] a forest–tundra zone of scattered patches of krummholz or stunted trees, with larger trees along rivers and on sheltered sites set in a matrix of tundra; and "open boreal forest" or "lichen woodland", consisting of open groves of erect trees underlain by a carpet of Cladonia spp. lichens.[21] The proportion of trees to lichen mat increases southwards towards the "forest line", where trees cover 50 percent or more of the landscape.[8][23]

Antarctic

A southern treeline exists in the New Zealand Subantarctic Islands and the Australian Macquarie Island, with places where mean annual temperatures above 5 °C (41 °F) support trees and woody plants, and those below 5 °C (41 °F) do not.[24] Another treeline exists in the southwestern most parts of the Magellanic subpolar forests ecoregion, where the forest merges into the subantarctic tundra (termed Magellanic moorland or Magellanic tundra).[25] For example, the northern halves of Hoste and Navarino Islands have Nothofagus antarctica forests but the southern parts consist of moorlands and tundra.

Other tree lines

Several other reasons may cause the environment to be too extreme for trees to grow. This can include geothermal exposure associated with hot springs or volcanoes, such as at Yellowstone; high soil acidity near bogs; high salinity associated with playas or salt lakes; or ground that is saturated with groundwater that excludes oxygen from the soil, which most tree roots need for growth. The margins of muskegs and bogs are common examples of these types of open area. However, no such line exists for swamps, where trees, such as bald cypress and the many mangrove species, have adapted to growing in permanently waterlogged soil. In some colder parts of the world there are tree lines around swamps, where there are no local tree species that can develop. There are also man-made pollution tree lines in weather-exposed areas, where new tree lines have developed because of the increased stress caused by pollution. Examples are found around Nikel in Russia and previously in the Erzgebirge.

Tree species near tree line

Some typical Arctic and alpine tree line tree species (note the predominance of conifers):

Eurasia

- Dahurian Larch (Larix gmelinii)

- Macedonian Pine (Pinus peuce)

- Swiss Pine (Pinus cembra)

- Mountain Pine (Pinus mugo)

- Arctic White Birch (Betula pubescens subsp. tortuosa)

- Rowan[26] (Sorbus aucuparia)

North America

- Subalpine Fir (Abies lasiocarpa)[7]:106

- Subalpine Larch (Larix lyallii)[27]

- Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmannii)[7]:106

- Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis)[27]

- Great Basin Bristlecone Pine (Pinus longaeva)

- Rocky Mountains Bristlecone Pine (Pinus aristata)

- Foxtail Pine (Pinus balfouriana)

- Limber Pine (Pinus flexilis)

- Potosi Pinyon (Pinus culminicola)

- Black spruce (Picea mariana)[1]:53

- White spruce (Picea glauca)

- Tamarack Larch (Larix laricina)

- Hartweg's Pine (Pinus hartwegii)

South America

- Antarctic Beech (Nothofagus antarctica)

- Lenga Beech (Nothofagus pumilio)[28]

- Alder (Alnus acuminata)

- Pino del cerro (Podocarpus parlatorei)

- Polylepis (Polylepis tarapacana)

- Eucalyptus (not native to South America but grown in large amounts in the high Andes).[29]

Australia

- Snow Gum (Eucalyptus pauciflora)

Worldwide distribution

Alpine tree lines

The alpine tree line at a location is dependent on local variables, such as aspect of slope, rain shadow and proximity to either geographical pole. In addition, in some tropical or island localities, the lack of biogeographical access to species that have evolved in a subalpine environment can result in lower tree lines than one might expect by climate alone.

Averaging over many locations and local microclimates, the treeline rises 75 metres (245 ft) when moving 1 degree south from 70 to 50°N, and 130 metres (430 ft) per degree from 50 to 30°N. Between 30°N and 20°S, the treeline is roughly constant, between 3,500 and 4,000 metres (11,500 and 13,100 ft).[30]

Here is a list of approximate tree lines from locations around the globe:

| Location | Approx. latitude | Approx. elevation of tree line | Notes | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (m) | (ft) | |||

| Finnmarksvidda, Norway | 69°N | 500 | 1,600 | At 71°N, near the coast, the tree-line is below sea level (Arctic tree line). |

| Abisko, Sweden | 68°N | 650 | 2,100 | [30] |

| Chugach Mountains, Alaska | 61°N | 700 | 2,300 | Tree line around 1,500 feet (460 m) or lower in coastal areas |

| Southern Norway | 61°N | 1,100 | 3,600 | Much lower near the coast, down to 500–600 metres (1,600–2,000 ft). |

| Scotland | 57°N | 500 | 1,600 | Strong maritime influence serves to cool summer and restrict tree growth[31]:79 |

| Northern Quebec | 56°N | 0 | 0 | The cold Labrador Current originating in the arctic makes eastern Canada the sea-level region with the most southern tree-line in the northern hemisphere. |

| Southern Urals | 55°N | 1,100 | 3,600 | |

| Canadian Rockies | 51°N | 2,400 | 7,900 | |

| Tatra Mountains | 49°N | 1,600 | 5,200 | |

| Olympic Mountains WA, United States | 47°N | 1,500 | 4,900 | Heavy winter snowpack buries young trees until late summer |

| Swiss Alps | 47°N | 2,200 | 7,200 | [32] |

| Mount Katahdin, Maine, United States | 46°N | 1,150 | 3,800 | |

| Eastern Alps, Austria, Italy | 46°N | 1,750 | 5,700 | More exposure to cold Russian winds than Western Alps |

| Sikhote-Alin, Russia | 46°N | 1,600 | 5,200 | [33] |

| Alps of Piedmont, Northwestern Italy | 45°N | 2,100 | 6,900 | |

| New Hampshire, United States | 44°N | 1,350 | 4,400 | [34] Some peaks have even lower treelines because of fire and subsequent loss of soil, such as Grand Monadnock and Mount Chocorua. |

| Wyoming, United States | 43°N | 3,000 | 9,800 | |

| Rila and Pirin Mountains, Bulgaria | 42°N | 2,300 | 7,500 | Up to 2,600 m (8,500 ft) on favorable locations. Mountain Pine is the most common tree line species. |

| Pyrenees Spain, France, Andorra | 42°N | 2,300 | 7,500 | Mountain Pine is the tree line species |

| Wasatch Mountains, Utah, United States | 40°N | 2,900 | 9,500 | Higher (nearly 11,000 feet or 3,400 metres in the Uintas) |

| Rocky Mountain NP, CO, United States | 40°N | 3,650 | 12,000 | [35] Some nearby mountain passes exceed this tree line |

| Yosemite, CA, United States | 38°N | 3,200 | 10,500 | [36] West side of Sierra Nevada |

| 3,350 | 11,000 | [36] East side of Sierra Nevada, with a large subalpine zone and smaller montane zone | ||

| Sierra Nevada, Spain | 37°N | 2,400 | 7,900 | Precipitation low in summer |

| Japanese Alps | 36°N | 2,900 | 9,500 | |

| Khumbu, Himalaya | 28°N | 4,200 | 13,800 | [30] |

| Yushan, Taiwan | 23°N | 3,600 | 11,800 | [37] Strong winds and poor soil restrict further grow of trees. |

| Hawaii, United States | 20°N | 3,000 | 9,800 | [30] Geographic isolation and no local tree species with high tolerance to cold temperatures. |

| Pico de Orizaba, Mexico | 19°N | 4,000 | 13,100 | [32] |

| Costa Rica | 9.5°N | 3,400 | 11,200 | |

| Mount Kinabalu, Borneo | 6.1°N | 3,400 | 11,200 | [38] |

| Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania | 3°S | 3,100 | 10,200 | [30] Upper limit of forest trees; woody ericaeous scrub grows up to 3900m |

| New Guinea | 6°S | 3,850 | 12,600 | [30] |

| Andes, Peru | 11°S | 3,900 | 12,800 | East side; on west side tree growth is restricted by dryness |

| Andes, Bolivia | 18°S | 5,200 | 17,100 | Western Cordillera; highest treeline in the world on the slopes of Sajama Volcano (Polylepis tarapacana) |

| 4,100 | 13,500 | Eastern Cordillera; treeline is lower because of lower solar radiation (more humid climate) | ||

| Sierra de Córdoba, Argentina | 31°S | 2,000 | 6,600 | Precipitation low above trade winds, also high exposure |

| Australian Alps, Australia | 36°S | 2,000 | 6,600 | West side of Australian Alps |

| 1,700 | 5,600 | East side of Australian Alps | ||

| Andes, Laguna del Laja, Chile | 37°S | 1,600 | 5,200 | Temperature rather than precipitation restricts tree growth[39] |

| Mount Taranaki, North Island, New Zealand | 39°S | 1,500 | 4,900 | Strong maritime influence serves to cool summer and restrict tree growth |

| Tasmania, Australia | 41°S | 1,200 | 3,900 | Cold winters, strong cold winds and cool summers with occasional summer snow restrict tree growth |

| Fiordland, South Island, New Zealand | 45°S | 950 | 3,100 | Cold winters, strong cold winds and cool summers with occasional summer snow restrict tree growth |

| Torres del Paine, Chile | 51°S | 950 | 3,100 | Strong influence from the Southern Patagonian Ice Field serves to cool summer and restrict tree growth[40] |

| Navarino Island, Chile | 55°S | 600 | 2,000 | Strong maritime influence serves to cool summer and restrict tree growth[40] |

Arctic tree lines

Like the alpine tree lines shown above, polar tree lines are heavily influenced by local variables such as aspect of slope and degree of shelter. In addition, permafrost has a major impact on the ability of trees to place roots into the ground. When roots are too shallow, trees are susceptible to windthrow and erosion. Trees can often grow in river valleys at latitudes where they could not grow on a more exposed site. Maritime influences such as ocean currents also play a major role in determining how far from the equator trees can grow as well as the warm summers experienced in extreme continental climates. In northern inland Scandinavia there is substantial maritime influence on high parallels that keep winters relatively mild, but enough inland effect to have summers well above the threshold for the tree line. Here are some typical polar treelines:

| Location | Approx. longitude | Approx. latitude of tree line | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Norway | 24°E | 70°N | The North Atlantic current makes Arctic climates in this region warmer than other coastal locations at comparable latitude. In particular the mildness of winters prevents permafrost. |

| West Siberian Plain | 75°E | 66°N | |

| Central Siberian Plateau | 102°E | 72°N | Extreme continental climate means the summer is warm enough to allow tree growth at higher latitudes, extending to northernmost forests of the world at 72°28'N at Ary-Mas (102° 15' E) in the Novaya River valley, a tributary of the Khatanga River and the more northern Lukunsky grove at 72°31'N, 105° 03' E east from Khatanga River. |

| Russian Far East (Kamchatka and Chukotka) | 160°E | 60°N | The Oyashio Current and strong winds affect summer temperatures to prevent tree growth. The Aleutian Islands are almost completely treeless. |

| Alaska | 152°W | 68°N | Trees grow north to the south-facing slopes of the Brooks Range. The mountains block cold air coming off of the Arctic Ocean. |

| Northwest Territories, Canada | 132°W | 69°N | Reaches north of the Arctic Circle because of the continental nature of the climate and warmer summer temperatures. |

| Nunavut | 95°W | 61°N | Influence of the very cold Hudson Bay moves the treeline southwards. |

| Labrador Peninsula | 72°W | 56°N | Very strong influence of the Labrador Current on summer temperatures as well as altitude effects (much of Labrador is a plateau). In parts of Labrador, the treeline extends as far south as 53°N. Along the coast the northernmost trees are at 58°N in Napartok Bay. |

| Greenland | 50°W | 64°N | Determined by experimental tree planting in the absence of native trees because of isolation from natural seed sources; a very few trees are surviving, but growing slowly, at Søndre Strømfjord, 67°N. There is one natural forest in the Qinngua Valley. |

Antarctic tree lines

Trees exist on Tierra del Fuego (55°S) at the southern end of South America, but generally not on subantarctic islands and not in Antarctica. Therefore, there is no explicit Antarctic tree line.

Kerguelen Island (49°S), South Georgia (54°S), and other subantarctic islands are all so heavily wind-exposed and with a too-cold summer climate (tundra) that none have any indigenous tree species. The Falkland Islands (51°S) summer temperature is near the limit, but the islands are also treeless, although some planted trees exist.

Antarctic Peninsula is the northernmost point in Antarctica (63°S) and has the mildest weather—it is located 1,080 kilometres (670 mi) from Cape Horn on Tierra del Fuego—yet no trees survive there; only a few mosses, lichens, and species of grass do so. In addition, no trees survive on any of the subantarctic islands near the peninsula.

Southern Rata forests exist on Enderby Island and Auckland Islands (both 50°S) and these grow up to an elevation of 370 metres (1,200 ft) in sheltered valleys. These trees seldom grow above 3 m (9.8 ft) in height and they get smaller as one gains altitude, so that by 180 m (600 ft) they are waist-high. These islands have only between 600 and 800 hours of sun annually. Campbell Island (52°S) further south is treeless, except for one stunted pine, planted by scientists. The climate on these islands is not severe, but tree growth is limited by almost continual rain and wind. Summers are very cold with an average January temperature of 9 °C (48 °F). Winters are mild 5 °C (41 °F) but wet. Macquarie Island (Australia) is located at 54°S and has no vegetation beyond snow grass and alpine grasses and mosses.

Desert tree lines

In Southwestern United States like Arizona, New Mexico, and Nevada, the tree line is categorized at the point where the most extreme amounts of rainfall and temperature are sufficient for tree growth. Due to wildfire risk, the tree line may be permanently altered by humans during prescribed fires, and most of the times, there is only one tree line the separates elevated temperate grassland biomes and alpine forests. There is no alpine forest and tundra separation point unless the elevation is higher than 15,000 feet. Mountain ranges in these states are between 2,000 and 12,000 feet in elevation on average, though.

| Location | Approx. longitude | Approx. latitude of tree line | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Santa Catalina Mountains, Arizona | 110°W | 32°N | The tree line is present at about 4,800 feet in elevation, but it can be lower in other areas. Stunted Ponderosa pine trees are present reaching heights of about 15 feet. Some have been burnt due to excessive heat and low rainfall. |

| Crown King, Arizona | 112°W | 34°N | At 5,200 feet. A variety of trees are present, but mainly ponderosa pine and pinyon pine are in healthy condition at 6,000 feet. Trees mature at 7,500 feet, and tundra / cold weather seasonally (November to January) affects tree growth at 8,100 feet. |

| Sedona, Arizona and surrounding areas | 112°W | 34°N | Tree line at 4,200 feet above sea level. Small pinyon trees are present at 3,500 feet as well. |

Long-term monitoring of alpine treelines

There are several monitoring protocols developed for long term monitoring of alpine biodiversity. One such network which is developed on the line of Global Observation Research Initiative in Alpine Environments (GLORIA), in India HIMADRI.

See also

| Look up tree line in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Montane ecosystems

- Ecotone: a transition between two adjacent ecological communities

- Edge effects: the effect of contrasting environments on an ecosystem

- Massenerhebung effect

- Snow line

References

- Elliott-Fisk, D.L. (2000). "The Taiga and Boreal Forest". In Barbour, M.G.; Billings, M.D. (eds.). North American Terrestrial Vegetation (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55986-7.

- Jørgensen, S.E. (2009). Ecosystem Ecology. Academic Press. ISBN 978-0-444-53466-8.

- Körner, C.; Riedl, S. (2012). Alpine Treelines: Functional Ecology of the Global High Elevation Tree Limits. Springer. ISBN 9783034803960.

- Zwinger, A.; Willard, B.E. (1996). Land Above the Trees: A Guide to American Alpine Tundra. Big Earth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-55566-171-7.

- Körner, C (2003). Alpine plant life: functional plant ecology of high mountain ecosystems. Springer. ISBN 978-3-540-00347-2.

- "Alpine Tundra Ecosystem". Rocky Mountain National Park. National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-05-13.

- Peet, R.K. (2000). "Forests and Meadows of the Rocky Mountains". In Barbour, M.G.; Billings, M.D. (eds.). North American Terrestrial Vegetation (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-55986-7.

- Arno, S.F. (1984). Timberline: Mountain and Arctic Forest Frontiers. Seattle, WA: The Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-085-6.

- Baker, F.S. (1944). "Mountain climates of the western United States". Ecological Monographs. 14 (2): 223–254. doi:10.2307/1943534. JSTOR 1943534.

- Geiger, R. (1950). The Climate near the Ground. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Tranquillini, W. (1979). Physiological Ecology of the Alpine Timberline: tree existence at high altitudes with special reference to the European Alps. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-3642671074.

- Coates, K.D.; Haeussler, S.; Lindeburgh, S; Pojar, R.; Stock, A.J. (1994). Ecology and silviculture of interior spruce in British Columbia. OCLC 66824523.

- Viereck, L.A. (1979). "Characteristics of treeline plant communities in Alaska". Holarctic Ecology. 2 (4): 228–238. JSTOR 3682417.

- Viereck, L.A.; Van Cleve, K.; Dyrness, C. T. (1986). "Forest ecosystem distribution in the taiga environment". In Van Cleve, K.; Chapin, F.S.; Flanagan, P.W.; Viereck, L.A.; Dyrness, C.T. (eds.). Forest Ecosystems in the Alaskan Taiga. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag. pp. 22–43. doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-4902-3_3. ISBN 978-1461249023.

- Sowell, J.B.; McNulty, S.P.; Schilling, B.K. (1996). "The role of stem recharge in reducing the winter desiccation of Picea engelmannii (Pinaceae) needles at alpine timberline". American Journal of Botany. 83 (10): 1351–1355. doi:10.2307/2446122. JSTOR 2446122.

- Shaw, C.H. (1909). "The causes of timberline on mountains: the role of snow". Plant World. 12: 169–181.

- Bradley, Raymond S. (1999). Paleoclimatology: reconstructing climates of the Quaternary. 68. Academic Press. p. 344. ISBN 978-0123869951.

- Baldwin, B. G. (2002). The Jepson desert manual: vascular plants of southeastern California. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22775-0.

- Pienitz, Reinhard; Douglas, Marianne S. V.; Smol, John P. (2004). Long-term environmental change in Arctic and Antarctic lakes. Springer. p. 102. ISBN 978-1402021268.

- Timoney, K.P.; La Roi, G.H.; Zoltai, S.C.; Robinson, A.L. (1992). "The high subarctic forest–tundra of northwestern Canada: position, width, and vegetation gradients in relation to climate". Arctic. 45 (1): 1–9. doi:10.14430/arctic1367. JSTOR 40511186.

- Löve, Dd (1970). "Subarctic and subalpine: where and what?". Arctic and Alpine Research. 2 (1): 63–73. doi:10.2307/1550141. JSTOR 1550141.

- Hare, F. Kenneth; Ritchie, J.C. (1972). "The boreal bioclimates". Geographical Review. 62 (3): 333–365. doi:10.2307/213287. JSTOR 213287.

- R.A., Black; Bliss, L.C. (1978). "Recovery sequence of Picea mariana–Vaccinium uliginosum forests after burning near Inuvik, Northwest Territories, Canada". Canadian Journal of Botany. 56 (6): 2020–2030. doi:10.1139/b78-243.

- "Antipodes Subantarctic Islands tundra". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- "Magellanic subpolar Nothofagus forests". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund.

- Chalupa, V. (1992). "Micropropagation of European Mountain Ash (Sorbus aucuparia L.) and Wild Service Tree [Sorbus torminalis (L.) Cr.]". In Bajaj, Y.P.S. (ed.). High-Tech and Micropropagation II. Biotechnology in Agriculture and Forestry. 18. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 211–226. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-76422-6_11. ISBN 978-3-642-76424-0.

- "Treeline". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 2011-10-21. Retrieved 2011-06-22.

- Fajardo, A; Piper, FI; Cavieres, LA (2011). "Distinguishing local from global climate influences in the variation of carbon status with altitude in a tree line species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 20 (2): 307–318. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00598.x.

- Dickinson, Joshua C. (1969). "The Eucalypt in the Sierra of Southern Peru". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 59 (2): 294–307. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1969.tb00672.x. ISSN 0004-5608. JSTOR 2561632.

- Körner, Ch (1998). "A re-assessment of high elevation treeline positions and their explanation" (PDF). Oecologia. 115 (4): 445–459. Bibcode:1998Oecol.115..445K. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.454.8501. doi:10.1007/s004420050540. PMID 28308263.

- "Action For Scotland's Biodiversity" (PDF).

- Körner, Ch. "High Elevation Treeline Research". Archived from the original on 2011-05-14. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- "Physiogeography of the Russian Far East".

- "Mount Washington State Park". New Hampshire State Parks. Archived from the original on 2013-04-03. Retrieved 2013-08-22.

Tree line, the elevation above which trees do not grow, is about 4,400 feet in the White Mountains, nearly 2,000 feet below the summit of Mt. Washington.

- "Tree Line – What Elevation Is It In The Rockies?". Jake's Nature Blog. 31 August 2017. Retrieved 2019-07-23.

- Schoenherr, Allan A. (1995). A Natural History of California. UC Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06922-0.

- "台灣地帶性植被之區劃與植物區系之分區" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-11-29.

- "Mount Kinabalu National Park". www.ecologyasia.com. Ecology Asia. 4 September 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.

- Lara, Antonio; Villalba, Ricardo; Wolodarsky-Franke, Alexia; Aravena, Juan Carlos; Luckman, Brian H.; Cuq, Emilio (2005). "Spatial and temporal variation in Nothofagus pumilio growth at tree line along its latitudinal range (35°40′–55° S) in the Chilean Andes" (PDF). Journal of Biogeography. 32 (5): 879–893. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01191.x.

- Aravena, Juan C.; Lara, Antonio; Wolodarsky-Franke, Alexia; Villalba, Ricardo; Cuq, Emilio (2002). "Tree-ring growth patterns and temperature reconstruction from Nothofagus pumilio (Fagaceae) forests at the upper tree line of southern, Chilean Patagonia". Revista Chilena de Historia Natural. 75 (2). doi:10.4067/S0716-078X2002000200008.

Further reading

- Arno, S.F.; Hammerly, R.P. (1984). Timberline. Mountain and Arctic Forest Frontiers. Seattle: The Mountaineers. ISBN 978-0-89886-085-6.

- Beringer, Jason; Tapper, Nigel J.; McHugh, Ian; Chapin, F. S., III; et al. (2001). "Impact of Arctic treeline on synoptic climate". Geophysical Research Letters. 28 (22): 4247–4250. Bibcode:2001GeoRL..28.4247B. doi:10.1029/2001GL012914.

- Ødum, S (1979). "Actual and potential tree line in the North Atlantic region, especially in Greenland and the Faroes". Holarctic Ecology. 2 (4): 222–227. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.1979.tb01293.x.

- Ødum, S (1991). "Choice of species and origins for arboriculture in Greenland and the Faroe Islands". Dansk Dendrologisk Årsskrift. 9: 3–78.

- Singh, C.P.; Panigrahy, S.; Parihar, J.S.; Dharaiya, N. (2013). "Modeling environmental niche of Himalayan birch and remote sensing based vicarious validation" (PDF). Tropical Ecology. 54 (3): 321–329.

- Singh, C.P.; Panigrahy, S.; Thapliyal, A.; Kimothi, M.M.; Soni, P.; Parihar, J.S. (2012). "Monitoring the alpine treeline shift in parts of the Indian Himalayas using remote sensing" (PDF). Current Science. 102 (4): 559–562. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-16.

- Panigrahy, Sushma; Singh, C.P.; Kimothi, M.M.; Soni, P.; Parihar, J.S. (2010). "The Upward Migration of Alpine Vegetation as an Indicator of Climate Change: Observations from Indian Himalayan region using Remote Sensing Data" (PDF). NNRMS(B). 35: 73–80. Archived from the original on November 24, 2011.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Singh, C.P. (2008). "Alpine ecosystems in relation to climate change". ISG Newsletter. 14: 54–57.

- Ameztegui, A; Coll, L; Brotons, L; Ninot, JM (2016). "Land-use legacies rather than climate change are driving the recent upward shift of the mountain tree line in the Pyrenees" (PDF). Global Ecology and Biogeography. 25 (3): 263. doi:10.1111/geb.12407. hdl:10459.1/65151.