Lake Winnipeg

Lake Winnipeg (French: Lac Winnipeg) is a very large, relatively shallow 24,514-square-kilometre (9,465 sq mi) lake in North America, in the province of Manitoba, Canada. Its southern end is about 55 kilometres (34 mi) north of the city of Winnipeg. Lake Winnipeg is Canada's sixth-largest freshwater lake[3] and the third-largest freshwater lake contained entirely within Canada, but it is relatively shallow (mean depth of 12 m [39 ft])[4] excluding a narrow 36 m (118 ft) deep channel between the northern and southern basins. It is the eleventh-largest freshwater lake on Earth. The lake's east side has pristine boreal forests and rivers that were recently inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The lake is 416 km (258 mi) from north to south, with remote sandy beaches, large limestone cliffs, and many bat caves in some areas. Manitoba Hydro uses the lake as one of the largest reservoirs in the world. There are many islands, most of them undeveloped.

| Lake Winnipeg | |

|---|---|

Map | |

| Location | Manitoba, Canada |

| Coordinates | 52°7′N 97°15′W |

| Type | Formerly part of the glacial Lake Agassiz, reservoir |

| Primary inflows | Winnipeg River, Saskatchewan River, Red River |

| Primary outflows | Nelson River |

| Catchment area | 982,900 km2 (379,500 sq mi) |

| Basin countries | Canada, United States |

| Max. length | 416 km (258 mi) |

| Max. width | 100 km (60 mi) (N Basin) 40 km (20 mi) (S Basin) |

| Surface area | 24,514 km2 (9,465 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 12 m (39 ft) |

| Max. depth | 36 m (118 ft) |

| Water volume | 284 km3 (68 cu mi)[1] |

| Residence time | 3.5 years [2] |

| Shore length1 | 1,858 km (1,155 mi) |

| Surface elevation | 217 m (712 ft) |

| Settlements | Gimli, Manitoba |

| 1 Shore length is not a well-defined measure. | |

The Sagkeeng First Nation holds a reserve on Turtle Island, in the southern part of the lake. The Anishinaabe people have been in this area for hundreds of years.

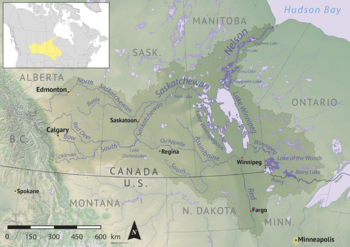

Hydrography

Lake Winnipeg has the largest watershed of any lake in Canada, receiving water from four U.S. states (North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota and Montana via tributaries of the Oldman River) and four Canadian provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario and Manitoba).[5] The lake's watershed measures about 982,900 square kilometres (379,500 sq mi).[6] Its drainage is about 40 times larger than its surface, a ratio bigger than any other large lake in the world.

Lake Winnipeg drains northward into the Nelson River at an average annual rate of 2,066 cubic metres per second (72,960 cu ft/s), and forms part of the Hudson Bay watershed, which is one of the largest drainage basins in the world. This watershed area was known as Rupert's Land when the Hudson's Bay Company was chartered in 1670.

Tributaries

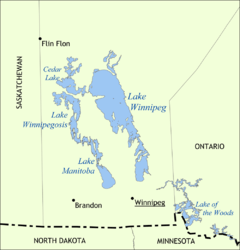

The Saskatchewan River flows in from the west through Cedar Lake, the Red River (including Assiniboine River) flows in from the south, and the Winnipeg River (draining Lake of the Woods, Rainy River and Rainy Lake) enters from the southeast. The Dauphin River enters from the west, draining Lake Manitoba and Lake Winnipegosis. The Bloodvein River, Berens River, Poplar River and the Manigotagan River flow in from the eastern side of the lake which is within the Canadian Shield.

Other tributaries of Lake Winnipeg (clockwise from the south end) include; Meleb Drain (drainage canal), Drunken River, Icelandic River, Washow Bay Creek, Sugar Creek, Beaver Creek, Mill Creek, Moose Creek, Fisher River, Jackhead River, Kinwow Bay Creek, Jackpine Creek, Mantagao River, Solomons Creek, Jumping Creek, Warpath River, South Two Rivers, North Two Rivers, South Twin Creek, North Twin Creek, Saskachaywiak Creek, Eating Point Creek, Woody Point Creeks, Muskwa Creek, Buffalo Creek, Fiddler Creek, Sturgeon Creek, Hungry River, Cypress Creek, William River, Bélanger River, Mukutawa River, Crane Creek, Kapawekapuk Creek, Marchand Creek, Leaf River, Pigeon River, Taskapekawe Creek, Bradbury River, Petopeko Creek, Loon Creek, Sanders Creek, Rice River, Wanipigow River, Barrie Creek, Mutch Creek, Sandy River, Black River, Sandy Creek, Catfish Creek, Jackfish Creek, Marais Creek, Brokenhead River and Devils Creek.[7][8]

Geology

Lake Winnipeg and Lake Manitoba are remnants of prehistoric Glacial Lake Agassiz, although there is evidence of a desiccated south basin of Lake Winnipeg approximately 4,000 years ago. The area between the lakes is called the Interlake Region, and the whole region is called the Manitoba Lowlands.

Natural history

Fish

The varying habitats found within the lake support a large number of fish species, more than any other lake in Canada west of the Great Lakes.[5] Sixty of seventy-nine native species found in Manitoba are present in the lake.[9] Families represented include lampreys (Petromyzontidae), sturgeon (Acipenseridae), mooneyes (Hiodontidae), minnows (Cyprinidae), suckers (Catostomidae), catfishes (Ictaluridae), pikes (Esocidae), trout and whitefish (Salmonidae), troutperch (Percopsidae), codfishes (Gadidae), sticklebacks (Gasterosteidae), sculpins (Cottidae), sunfishes (Centrarchidae), perch (Percidae), and drums (Sciaenidae).[9]

Two fish species present in the lake are considered to be at risk, the shortjaw cisco and the bigmouth buffalo.[10][11]

Rainbow trout and brown trout are stocked in Manitoba waters by provincial fisheries as part of a put and take program to support angling opportunities. Neither species is able to sustain itself independently in Manitoba.[12] Smallmouth bass was first recorded from the lake in 2002, indicating populations introduced elsewhere in the watershed are now present in the lake.[13] White bass were first recorded from the lake in 1963, ten years after being introduced into Lake Ashtabula in North Dakota.[14] Common carp were introduced to the lake through the Red River of the North and are firmly established.[15]

Birds

Lake Winnipeg provides feeding and nesting sites for a wide variety of birds associated with water during the summer months.

Isolated, uninhabited islands provide nesting sites for colonial nesting birds including pelicans, gulls and terns. Large marshes, shores and shallows allow these birds to successfully feed themselves and their young. Pipestone Rocks are considered a globally significant site for American white pelicans. In 1998, an estimated 3.7% of the world's population of this bird at the time were counted nesting on the rocky outcrops.[16] The same site is significant within North America for the numbers of colonial waterbirds using the area, especially Common terns.[16] Other globally significant nesting areas are found at Gull Island and Sandhill Island,[17] Little George Island[18] and Louis Island.[19] Birds nesting at these sites include Common and Caspian terns, Herring gull, Ring-billed gull, Double-crested cormorant and Greater scaup.

Lake Winnipeg has two sites considered globally important in the fall migration. Large populations of waterfowl and shorebirds use the sand bars east of Riverton as a staging area for fall migration.[20] The Netley-Libau Marsh, where the Red River enters Lake Winnipeg, is used by geese, ducks and swallows to gather for the southward migration.[21]

Piping Plovers, an endangered species of shorebird, are found in several locations around the lake. The Gull Bay Spits, south of the town of Grand Rapids are considered nationally significant nesting sites for this species.[22]

Protected areas

- Beaver Creek Provincial Park

- Camp Morton Provincial Park

- Elk Island Provincial Park

- Fisher Bay Provincial Park

- Grand Beach Provincial Park

- Hecla-Grindstone Provincial Park

- Hnausa Beach Provincial Park

- Kinwow Provincial Park

- Patricia Beach Provincial Park

- Sturgeon Bay Provincial Park

- Winnipeg Beach Provincial Park

Environmental issues

Lake Winnipeg is suffering from many environmental issues such as an explosion in the population of algae, caused by excessive amounts of phosphorus seeping into the lake, therefore not absorbing enough nitrogen.[23][24] The phosphorus levels are approaching a point that could be dangerous for human health.[25]

The Global Nature Fund declared Lake Winnipeg as the "threatened lake of the year" in 2013.[26]

In 2015, there was a major uptick of zebra mussels in Lake Winnipeg, the reduction of which is next to impossible because of a lack of natural predators in the lake. The mussels are devastating to the ecological opportunities of the lake.[27]

History

It is believed Henry Kelsey was the first European to see the lake, in 1690. He adopted the Cree language name for the lake: wīnipēk (ᐐᓂᐯᐠ), meaning "muddy waters". La Vérendrye referred to the lake as Ouinipigon when he built the first forts in the area in the 1730s. Later, the Red River Colony to its south took the lake's name for Winnipeg, the capital of Manitoba.

Lake Winnipeg lies along one of the oldest trading routes in North America to have flown the British flag. For several centuries, furs were traded along this route between York Factory on Hudson Bay[28] (which was the longtime headquarters for the Hudson's Bay Company) over Lake Winnipeg and the Red River Trails to the confluence of the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers at Saint Paul, Minnesota. This was a strategic trading route for the First British Empire. With the establishment of the Second British Empire after Britain's loss of the Thirteen Colonies, a significant increase in trade occurred over Lake Winnipeg between Rupert's Land and the United States.

Economy

Transportation

Because of its length, the Lake Winnipeg water system and the lake was an important transportation route in the province before the railways reached Manitoba. It continued to be a major transportation route even after the railways reached the province. In addition to aboriginal canoes and York boats, several steamboats plied the lake, including Anson Northup, City of Selkirk, Colvile, Keenora, Premier, Princess, Winnitoba, Wolverine and most recently the diesel-powered MS Lord Selkirk II passenger cruise ship.

Communities

Communities on the lake include Grand Marais, Lester Beach, Riverton, Gimli, Winnipeg Beach, Victoria Beach, Hillside beach, Pine Falls, Manigotagan, Berens River, Bloodvein, Sandy Hook, Albert Beach, Hecla Village and Grand Rapids. A number of pleasure beaches are found on the southern end of the lake, which are popular in the summer, attracting many visitors from Winnipeg, about 80 km south.

Commercial fisheries

Lake Winnipeg has important commercial fisheries. Its catch makes up a major part of Manitoba's $30 million per year fishing industry.[29] The lake was once the main source of goldeye in Canada, which is why the fish is sometimes called Winnipeg goldeye. Walleye and whitefish together account for over 90 percent of its commercial fishing.[30]

See also

Notes

- "Lake Winnipeg Quick Facts". Archived from the original on 11 March 2018. Retrieved 14 July 2014.

- Massive flood expected to take toll on Lake Winnipeg, feed algae blooms Winnipeg Free Press

- "Great Canadian Lakes". Archived from the original on 24 January 2007. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- International Lake Environment Committee Archived 10 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. pp. 10–11. ISBN 0887556787.

- "Canada Drainage Basins". The National Atlas of Canada, 5th edition. Natural Resources Canada. 1985. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- "Natural Resources Canada-Canadian Geographical Names (Lake Winnipeg)". Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- "Atlas of Canada Toporama". Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. pp. 249–257. ISBN 0887556787.

- "COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Shortjaw Cisco (Coregonus zenithicus) in Canada – 2009". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada, Environment. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Bigmouth Buffalo (Ictiobus cyprinellus) in Canada – 2009". Species at Risk Public Registry. Government of Canada, Environment. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. pp. 169–174. ISBN 0887556787.

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. pp. 221–222. ISBN 0887556787.

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. pp. 208–209. ISBN 0887556787.

- Stewart, Kenneth W.; Watkinson, Douglas A. (2004). The freshwater fishes of Manitoba. Manitoba: Univ. of Manitoba Press, CN. p. 22. ISBN 0887556787.

- "Pipestone Rocks". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Gull and Sandhill Island". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Little George Island". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Louis Island and Associated Reefs". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Riverton Sandy Bar". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Netley-Libau Marsh". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "Gull Bay Spits". Important Bird Areas Canada. Bird Studies Canada and Nature Canada. Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- $1.1M for Lake Winnipeg - Winnipeg Free Press

- Canada’s sickest lake Archived 28 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine, MacLean's Magazine

- "Lake Winnipeg at 'tipping point': report". CBC News. 31 May 2011.

- "Lake Winnipeg declared threatened lake of the year". Winnipeg Free Press. 5 February 2013.

- Lake Winnipeg a lost cause - CBC Online

- Fur Trade Canoe Routes of Canada/ Then and Now by Eric W. Morse Canada National and Historic Parks Branch, first printing 1969.

- "Manitoba Water Stewardship - Fisheries". Archived from the original on 25 September 2006. Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- "A profile of Manitoba's commercial fishery" (PDF). Manitoba Water Stewardship (Department, Government of Manitoba). 14 May 2010. Retrieved 29 July 2011.

References

- Canadian Action Party (2006) Canadian action party release Devils Lake ruling

- Casey, A. (November/December 2006) "Forgotten lake", Canadian Geographic, Vol. 126, Issue 6, pp. 62–78

- Chliboyko, J. (November/December 2003) "Trouble flows north", Canadian Geographic, Vol. 123, Issue 6, p. 23

- Economist, "Devil down south" (16 July 2005), Vol. 376, Issue 8435,. p. 34

- GreenPeace, "Algae bloom on Lake Winnipeg" (26 May 2008). Retrieved 2 February 2009

- Daily Commercial News and Construction Record, "Ottawa asked to help block water diversion project: Devils Lake outlet recommended by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers" (20 October 2003), Vol. 76, Issue 198,. p. 3

- Sexton, B. (2006) "Wastes control: Manitoba demands more scrutiny of North Dakota’s water diversion scheme", Outdoor Canada, Vol. 34, Issue 1, p. 32

- Warrington, Dr. P. (6 November 2001) "Aquatic pathogens: cyanophytes"

- Welch, M. A. (19 August 2008) "Winnipeg’s algae invasion was forewarned more than 30 years ago", The Canadian Press

- Macleans (14 June 2004) "What ails Lake Winnipeg" Vol. 117, Issue 24, p. 38.

- Wilderness Committee (2008) "Turning the tide on Lake Winnipeg and our health"

External links

![]()

- "Lake Winnipeg". The Canadian Encyclopedia

- Lake Winnipeg Research Consortium

- Manitoba Water Stewardship - Lake Winnipeg

- Satellite images of Lake Winnipeg

- Sail Lake Winnipeg

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lake Winnipeg. |