Light-emitting diode

A light-emitting diode (LED) is a semiconductor light source that emits light when current flows through it. Electrons in the semiconductor recombine with electron holes, releasing energy in the form of photons. The color of the light (corresponding to the energy of the photons) is determined by the energy required for electrons to cross the band gap of the semiconductor.[5] White light is obtained by using multiple semiconductors or a layer of light-emitting phosphor on the semiconductor device.[6]

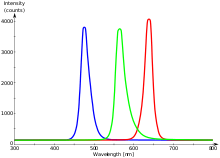

Blue, green, and red LEDs in 5 mm diffused case | |

| Working principle | Electroluminescence |

|---|---|

| Invented | H. J. Round (1907)[1] Oleg Losev (1927)[2] James R. Biard (1961)[3] Nick Holonyak (1962)[4] |

| First production | October 1962 |

| Pin configuration | Anode and cathode |

| Electronic symbol | |

.svg.png)

Appearing as practical electronic components in 1962, the earliest LEDs emitted low-intensity infrared (IR) light.[7] Infrared LEDs are used in remote-control circuits, such as those used with a wide variety of consumer electronics. The first visible-light LEDs were of low intensity and limited to red. Modern LEDs are available across the visible, ultraviolet (UV), and infrared wavelengths, with high light output.

Early LEDs were often used as indicator lamps, replacing small incandescent bulbs, and in seven-segment displays. Recent developments have produced high-output white light LEDs suitable for room and outdoor area lighting. LEDs have led to new displays and sensors, while their high switching rates are useful in advanced communications technology.

LEDs have many advantages over incandescent light sources, including lower energy consumption, longer lifetime, improved physical robustness, smaller size, and faster switching. LEDs are used in applications as diverse as aviation lighting, automotive headlamps, advertising, general lighting, traffic signals, camera flashes, lighted wallpaper, horticultural grow lights, and medical devices.[8]

Unlike a laser, the light emitted from an LED is neither spectrally coherent nor even highly monochromatic. However, its spectrum is sufficiently narrow that it appears to the human eye as a pure (saturated) color.[9][10] Also unlike most lasers, its radiation is not spatially coherent, so it cannot approach the very high brightnesses characteristic of lasers.

History

Discoveries and early devices

Electroluminescence as a phenomenon was discovered in 1907 by the British experimenter H. J. Round of Marconi Labs, using a crystal of silicon carbide and a cat's-whisker detector.[11][12] Russian inventor Oleg Losev reported creation of the first LED in 1927.[13] His research was distributed in Soviet, German and British scientific journals, but no practical use was made of the discovery for several decades.[14][15]

In 1936, Georges Destriau observed that electroluminescence could be produced when zinc sulphide (ZnS) powder is suspended in an insulator and an alternating electrical field is applied to it. In his publications, Destriau often referred to luminescence as Losev-Light. Destriau worked in the laboratories of Madame Marie Curie, also an early pioneer in the field of luminescence with research on radium.[16][17]

Hungarian Zoltán Bay together with György Szigeti pre-empted LED lighting in Hungary in 1939 by patenting a lighting device based on SiC, with an option on boron carbide, that emitted white, yellowish white, or greenish white depending on impurities present.[18]

Kurt Lehovec, Carl Accardo, and Edward Jamgochian explained these first LEDs in 1951 using an apparatus employing SiC crystals with a current source of a battery or a pulse generator and with a comparison to a variant, pure, crystal in 1953.[19][20]

Rubin Braunstein[21] of the Radio Corporation of America reported on infrared emission from gallium arsenide (GaAs) and other semiconductor alloys in 1955.[22] Braunstein observed infrared emission generated by simple diode structures using gallium antimonide (GaSb), GaAs, indium phosphide (InP), and silicon-germanium (SiGe) alloys at room temperature and at 77 kelvins.

In 1957, Braunstein further demonstrated that the rudimentary devices could be used for non-radio communication across a short distance. As noted by Kroemer[23] Braunstein "…had set up a simple optical communications link: Music emerging from a record player was used via suitable electronics to modulate the forward current of a GaAs diode. The emitted light was detected by a PbS diode some distance away. This signal was fed into an audio amplifier and played back by a loudspeaker. Intercepting the beam stopped the music. We had a great deal of fun playing with this setup." This setup presaged the use of LEDs for optical communication applications.

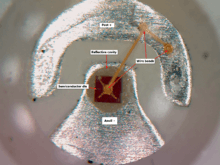

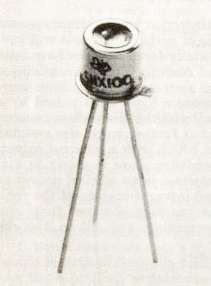

In September 1961, while working at Texas Instruments in Dallas, Texas, James R. Biard and Gary Pittman discovered near-infrared (900 nm) light emission from a tunnel diode they had constructed on a GaAs substrate.[7] By October 1961, they had demonstrated efficient light emission and signal coupling between a GaAs p-n junction light emitter and an electrically isolated semiconductor photodetector.[24] On August 8, 1962, Biard and Pittman filed a patent titled "Semiconductor Radiant Diode" based on their findings, which described a zinc-diffused p–n junction LED with a spaced cathode contact to allow for efficient emission of infrared light under forward bias. After establishing the priority of their work based on engineering notebooks predating submissions from G.E. Labs, RCA Research Labs, IBM Research Labs, Bell Labs, and Lincoln Lab at MIT, the U.S. patent office issued the two inventors the patent for the GaAs infrared light-emitting diode (U.S. Patent US3293513), the first practical LED.[7] Immediately after filing the patent, Texas Instruments (TI) began a project to manufacture infrared diodes. In October 1962, TI announced the first commercial LED product (the SNX-100), which employed a pure GaAs crystal to emit an 890 nm light output.[7] In October 1963, TI announced the first commercial hemispherical LED, the SNX-110.[25]

The first visible-spectrum (red) LED was demonstrated by Nick Holonyak, Jr. on October 9, 1962 while he was working for General Electric in Syracuse, New York.[26] Holonyak and Bevacqua reported this LED in the journal Applied Physics Letters on December 1, 1962.[27][28] M. George Craford,[29] a former graduate student of Holonyak, invented the first yellow LED and improved the brightness of red and red-orange LEDs by a factor of ten in 1972.[30] In 1976, T. P. Pearsall designed the first high-brightness, high-efficiency LEDs for optical fiber telecommunications by inventing new semiconductor materials specifically adapted to optical fiber transmission wavelengths.[31]

Initial commercial development

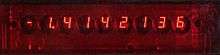

The first commercial visible-wavelength LEDs were commonly used as replacements for incandescent and neon indicator lamps, and in seven-segment displays,[32] first in expensive equipment such as laboratory and electronics test equipment, then later in such appliances as calculators, TVs, radios, telephones, as well as watches (see list of signal uses). Until 1968, visible and infrared LEDs were extremely costly, in the order of US$200 per unit, and so had little practical use.[33]

Hewlett-Packard (HP) was engaged in research and development (R&D) on practical LEDs between 1962 and 1968, by a research team under Howard C. Borden, Gerald P. Pighini and Mohamed M. Atalla at HP Associates and HP Labs.[34] During this time, Atalla launched a material science investigation program on gallium arsenide (GaAs), gallium arsenide phosphide (GaAsP) and indium arsenide (InAs) devices at HP,[35] and they collaborated with Monsanto Company on developing the first usable LED products.[36] The first usable LED products were HP's LED display and Monsanto's LED indicator lamp, both launched in 1968.[36] Monsanto was the first organization to mass-produce visible LEDs, using GaAsP in 1968 to produce red LEDs suitable for indicators.[33] Monsanto had previously offered to supply HP with GaAsP, but HP decided to grow its own GaAsP.[33] In February 1969, Hewlett-Packard introduced the HP Model 5082-7000 Numeric Indicator, the first LED device to use integrated circuit (integrated LED circuit) technology.[34] It was the first intelligent LED display, and was a revolution in digital display technology, replacing the Nixie tube and becoming the basis for later LED displays.[37]

Atalla left HP and joined Fairchild Semiconductor in 1969.[38] He was the vice president and general manager of the Microwave & Optoelectronics division,[39] from its inception in May 1969 up until November 1971.[40] He continued his work on LEDs, proposing they could be used for indicator lights and optical readers in 1971.[41] In the 1970s, commercially successful LED devices at less than five cents each were produced by Fairchild Optoelectronics. These devices employed compound semiconductor chips fabricated with the planar process (developed by Jean Hoerni,[42][43] based on Atalla's surface passivation method[44][45]). The combination of planar processing for chip fabrication and innovative packaging methods enabled the team at Fairchild led by optoelectronics pioneer Thomas Brandt to achieve the needed cost reductions.[46] LED producers continue to use these methods.[47]

The early red LEDs were bright enough only for use as indicators, as the light output was not enough to illuminate an area. Readouts in calculators were so small that plastic lenses were built over each digit to make them legible. Later, other colors became widely available and appeared in appliances and equipment.

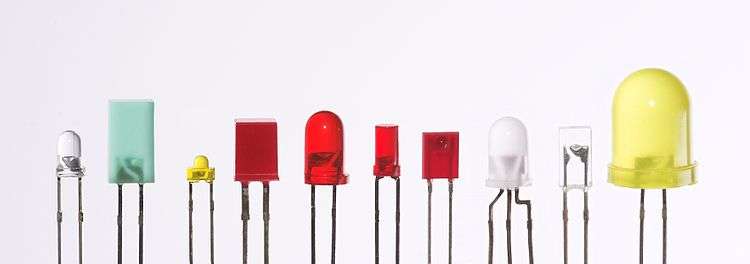

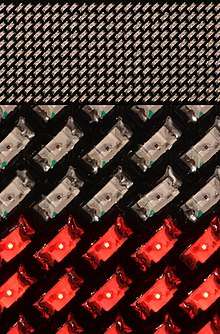

Early LEDs were packaged in metal cases similar to those of transistors, with a glass window or lens to let the light out. Modern indicator LEDs are packed in transparent molded plastic cases, tubular or rectangular in shape, and often tinted to match the device color. Infrared devices may be dyed, to block visible light. More complex packages have been adapted for efficient heat dissipation in high-power LEDs. Surface-mounted LEDs further reduce the package size. LEDs intended for use with fiber optics cables may be provided with an optical connector.

Blue LED

The first blue-violet LED using magnesium-doped gallium nitride was made at Stanford University in 1972 by Herb Maruska and Wally Rhines, doctoral students in materials science and engineering.[48][49] At the time Maruska was on leave from RCA Laboratories, where he collaborated with Jacques Pankove on related work. In 1971, the year after Maruska left for Stanford, his RCA colleagues Pankove and Ed Miller demonstrated the first blue electroluminescence from zinc-doped gallium nitride, though the subsequent device Pankove and Miller built, the first actual gallium nitride light-emitting diode, emitted green light.[50][51] In 1974 the U.S. Patent Office awarded Maruska, Rhines and Stanford professor David Stevenson a patent for their work in 1972 (U.S. Patent US3819974 A). Today, magnesium-doping of gallium nitride remains the basis for all commercial blue LEDs and laser diodes. In the early 1970s, these devices were too dim for practical use, and research into gallium nitride devices slowed.

In August 1989, Cree introduced the first commercially available blue LED based on the indirect bandgap semiconductor, silicon carbide (SiC).[52] SiC LEDs had very low efficiency, no more than about 0.03%, but did emit in the blue portion of the visible light spectrum.[53][54]

In the late 1980s, key breakthroughs in GaN epitaxial growth and p-type doping[55] ushered in the modern era of GaN-based optoelectronic devices. Building upon this foundation, Theodore Moustakas at Boston University patented a method for producing high-brightness blue LEDs using a new two-step process in 1991.[56]

Two years later, in 1993, high-brightness blue LEDs were demonstrated by Shuji Nakamura of Nichia Corporation using a gallium nitride growth process.[57][58][59] In parallel, Isamu Akasaki and Hiroshi Amano in Nagoya were working on developing the important GaN deposition on sapphire substrates and the demonstration of p-type doping of GaN. This new development revolutionized LED lighting, making high-power blue light sources practical, leading to the development of technologies like Blu-ray.

Nakamura was awarded the 2006 Millennium Technology Prize for his invention.[60] Nakamura, Hiroshi Amano and Isamu Akasaki were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2014 for the invention of the blue LED.[61] In 2015, a US court ruled that three companies had infringed Moustakas's prior patent, and ordered them to pay licensing fees of not less than US$13 million.[62]

In 1995, Alberto Barbieri at the Cardiff University Laboratory (GB) investigated the efficiency and reliability of high-brightness LEDs and demonstrated a "transparent contact" LED using indium tin oxide (ITO) on (AlGaInP/GaAs).

In 2001[63] and 2002,[64] processes for growing gallium nitride (GaN) LEDs on silicon were successfully demonstrated. In January 2012, Osram demonstrated high-power InGaN LEDs grown on silicon substrates commercially,[65] and GaN-on-silicon LEDs are in production at Plessey Semiconductors. As of 2017, some manufacturers are using SiC as the substrate for LED production, but sapphire is more common, as it has the most similar properties to that of gallium nitride, reducing the need for patterning the sapphire wafer (patterned wafers are known as epi wafers). Samsung, the University of Cambridge, and Toshiba are performing research into GaN on Si LEDs. Toshiba has stopped research, possibly due to low yields.[66][67][68][69][70][71][72] Some opt towards epitaxy, which is difficult on silicon, while others, like the University of Cambridge, opt towards a multi-layer structure, in order to reduce (crystal) lattice mismatch and different thermal expansion ratios, in order to avoid cracking of the LED chip at high temperatures (e.g. during manufacturing), reduce heat generation and increase luminous efficiency. Epitaxy (or patterned sapphire) can be carried out with nanoimprint lithography.[73][74][75][76][77][78][79] GaN is often deposited using Metalorganic vapour-phase epitaxy (MOCVD), and it also utilizes Lift-off.

White LEDs and the illumination breakthrough

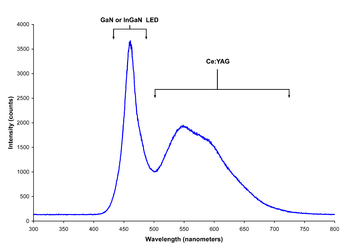

Even though white light can be created using individual red, green and blue LEDs, this results in poor color rendering, since only three narrow bands of wavelengths of light are being emitted. The attainment of high efficiency blue LEDs was quickly followed by the development of the first white LED. In this device a Y

3Al

5O

12:Ce (known as "YAG" or Ce:YAG phosphor) cerium doped phosphor coating produces yellow light through fluorescence. The combination of that yellow with remaining blue light appears white to the eye. Using different phosphors produces green and red light through fluorescence. The resulting mixture of red, green and blue is perceived as white light, with improved color rendering compared to wavelengths from the blue LED/YAG phosphor combination.

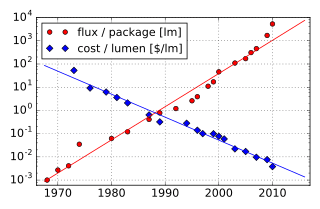

The first white LEDs were expensive and inefficient. However, the light output of LEDs has increased exponentially. The latest research and development has been propagated by Japanese manufacturers such as Panasonic, and Nichia, and by Korean and Chinese manufacturers such as Samsung, Kingsun, and others. This trend in increased output has been called Haitz's law after Dr. Roland Haitz.[80]

Light output and efficiency of blue and near-ultraviolet LEDs rose and the cost of reliable devices fell. This led to relatively high-power white-light LEDs for illumination, which are replacing incandescent and fluorescent lighting.[81][82]

Experimental white LEDs have been demonstrated to produce 303 lumens per watt of electricity (lm/w); some can last up to 100,000 hours.[83][84] However, commercially available LEDs have an efficiency of up to 223 lm/w.[85][86][87] Compared to incandescent bulbs, this is a huge increase in electrical efficiency, and even though LEDs are more expensive to purchase, overall cost is significantly cheaper than that of incandescent bulbs.[88]

The LED chip is encapsulated inside a small, plastic, white mold. It can be encapsulated using resin (polyurethane-based), silicone, or epoxy containing (powdered) Cerium doped YAG phosphor. After allowing the solvents to evaporate, the LEDs are often tested, and placed on tapes for SMT placement equipment for use in LED light bulb production. Encapsulation is performed after probing, dicing, die transfer from wafer to package, and wire bonding or flip chip mounting, perhaps using Indium tin oxide, a transparent electrical conductor. In this case, the bond wire(s) are attached to the ITO film that has been deposited in the LEDs. Some "remote phosphor" LED light bulbs use a single plastic cover with YAG phosphor for several blue LEDs, instead of using phosphor coatings on single chip white LEDs.

Physics of light production and emission

In a light emitting diode, the recombination of electrons and electron holes in a semiconductor produces light (be it infrared, visible or UV), a process called "electroluminescence". The wavelength of the light depends on the energy band gap of the semiconductors used. Since these materials have a high index of refraction, design features of the devices such as special optical coatings and die shape are required to efficiently emit light.

Colors

By selection of different semiconductor materials, single-color LEDs can be made that emit light in a narrow band of wavelengths from near-infrared through the visible spectrum and into the ultraviolet range. As the wavelengths become shorter, because of the larger band gap of these semiconductors, the operating voltage of the LED increases.

Blue and ultraviolet

| External video | |

|---|---|

| |

Blue LEDs have an active region consisting of one or more InGaN quantum wells sandwiched between thicker layers of GaN, called cladding layers. By varying the relative In/Ga fraction in the InGaN quantum wells, the light emission can in theory be varied from violet to amber.

Aluminium gallium nitride (AlGaN) of varying Al/Ga fraction can be used to manufacture the cladding and quantum well layers for ultraviolet LEDs, but these devices have not yet reached the level of efficiency and technological maturity of InGaN/GaN blue/green devices. If un-alloyed GaN is used in this case to form the active quantum well layers, the device emits near-ultraviolet light with a peak wavelength centred around 365 nm. Green LEDs manufactured from the InGaN/GaN system are far more efficient and brighter than green LEDs produced with non-nitride material systems, but practical devices still exhibit efficiency too low for high-brightness applications.

With AlGaN and AlGaInN, even shorter wavelengths are achievable. Near-UV emitters at wavelengths around 360–395 nm are already cheap and often encountered, for example, as black light lamp replacements for inspection of anti-counterfeiting UV watermarks in documents and bank notes, and for UV curing. While substantially more expensive, shorter-wavelength diodes are commercially available for wavelengths down to 240 nm.[89] As the photosensitivity of microorganisms approximately matches the absorption spectrum of DNA, with a peak at about 260 nm, UV LED emitting at 250–270 nm are expected in prospective disinfection and sterilization devices. Recent research has shown that commercially available UVA LEDs (365 nm) are already effective disinfection and sterilization devices.[90] UV-C wavelengths were obtained in laboratories using aluminium nitride (210 nm),[91] boron nitride (215 nm)[92][93] and diamond (235 nm).[94]

White

There are two primary ways of producing white light-emitting diodes. One is to use individual LEDs that emit three primary colors—red, green and blue—and then mix all the colors to form white light. The other is to use a phosphor material to convert monochromatic light from a blue or UV LED to broad-spectrum white light, similar to a fluorescent lamp. The yellow phosphor is cerium-doped YAG crystals suspended in the package or coated on the LED. This YAG phosphor causes white LEDs to look yellow when off, and the space between the crystals allow some blue light to pass through. Alternatively, white LEDs may use other phosphors like manganese(IV)-doped potassium fluorosilicate (PFS) or other engineered phosphors. PFS assists in red light generation, and is used in conjunction with conventional Ce:YAG phosphor. In LEDs with PFS phosphor, some blue light passes through the phosphors, the Ce:YAG phosphor converts blue light to green and red light, and the PFS phosphor converts blue light to red light. The color temperature of the LED can be controlled by changing the concentration of the phosphors.[95][96][97]

The 'whiteness' of the light produced is engineered to suit the human eye. Because of metamerism, it is possible to have quite different spectra that appear white. However, the appearance of objects illuminated by that light may vary as the spectrum varies. This is the issue of color rendition, quite separate from color temperature. An orange or cyan object could appear with the wrong color and much darker as the LED or phosphor does not emit the wavelength it reflects. The best color rendition LEDs use a mix of phosphors, resulting in less efficiency but better color rendering.

RGB systems

Mixing red, green, and blue sources to produce white light needs electronic circuits to control the blending of the colors. Since LEDs have slightly different emission patterns, the color balance may change depending on the angle of view, even if the RGB sources are in a single package, so RGB diodes are seldom used to produce white lighting. Nonetheless, this method has many applications because of the flexibility of mixing different colors,[98] and in principle, this mechanism also has higher quantum efficiency in producing white light.[99]

There are several types of multicolor white LEDs: di-, tri-, and tetrachromatic white LEDs. Several key factors that play among these different methods include color stability, color rendering capability, and luminous efficacy. Often, higher efficiency means lower color rendering, presenting a trade-off between the luminous efficacy and color rendering. For example, the dichromatic white LEDs have the best luminous efficacy (120 lm/W), but the lowest color rendering capability. However, although tetrachromatic white LEDs have excellent color rendering capability, they often have poor luminous efficacy. Trichromatic white LEDs are in between, having both good luminous efficacy (>70 lm/W) and fair color rendering capability.

One of the challenges is the development of more efficient green LEDs. The theoretical maximum for green LEDs is 683 lumens per watt but as of 2010 few green LEDs exceed even 100 lumens per watt. The blue and red LEDs approach their theoretical limits.

Multicolor LEDs also offer a new means to form light of different colors. Most perceivable colors can be formed by mixing different amounts of three primary colors. This allows precise dynamic color control. However, this type of LED's emission power decays exponentially with rising temperature,[100] resulting in a substantial change in color stability. Such problems inhibit industrial use. Multicolor LEDs without phosphors cannot provide good color rendering because each LED is a narrowband source. LEDs without phosphor, while a poorer solution for general lighting, are the best solution for displays, either backlight of LCD, or direct LED based pixels.

Dimming a multicolor LED source to match the characteristics of incandescent lamps is difficult because manufacturing variations, age, and temperature change the actual color value output. To emulate the appearance of dimming incandescent lamps may require a feedback system with color sensor to actively monitor and control the color.[101]

Phosphor-based LEDs

This method involves coating LEDs of one color (mostly blue LEDs made of InGaN) with phosphors of different colors to form white light; the resultant LEDs are called phosphor-based or phosphor-converted white LEDs (pcLEDs).[102] A fraction of the blue light undergoes the Stokes shift, which transforms it from shorter wavelengths to longer. Depending on the original LED's color, various color phosphors are used. Using several phosphor layers of distinct colors broadens the emitted spectrum, effectively raising the color rendering index (CRI).[103]

Phosphor-based LEDs have efficiency losses due to heat loss from the Stokes shift and also other phosphor-related issues. Their luminous efficacies compared to normal LEDs depend on the spectral distribution of the resultant light output and the original wavelength of the LED itself. For example, the luminous efficacy of a typical YAG yellow phosphor based white LED ranges from 3 to 5 times the luminous efficacy of the original blue LED because of the human eye's greater sensitivity to yellow than to blue (as modeled in the luminosity function). Due to the simplicity of manufacturing, the phosphor method is still the most popular method for making high-intensity white LEDs. The design and production of a light source or light fixture using a monochrome emitter with phosphor conversion is simpler and cheaper than a complex RGB system, and the majority of high-intensity white LEDs presently on the market are manufactured using phosphor light conversion.

Among the challenges being faced to improve the efficiency of LED-based white light sources is the development of more efficient phosphors. As of 2010, the most efficient yellow phosphor is still the YAG phosphor, with less than 10% Stokes shift loss. Losses attributable to internal optical losses due to re-absorption in the LED chip and in the LED packaging itself account typically for another 10% to 30% of efficiency loss. Currently, in the area of phosphor LED development, much effort is being spent on optimizing these devices to higher light output and higher operation temperatures. For instance, the efficiency can be raised by adapting better package design or by using a more suitable type of phosphor. Conformal coating process is frequently used to address the issue of varying phosphor thickness.

Some phosphor-based white LEDs encapsulate InGaN blue LEDs inside phosphor-coated epoxy. Alternatively, the LED might be paired with a remote phosphor, a preformed polycarbonate piece coated with the phosphor material. Remote phosphors provide more diffuse light, which is desirable for many applications. Remote phosphor designs are also more tolerant of variations in the LED emissions spectrum. A common yellow phosphor material is cerium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet (Ce3+:YAG).

White LEDs can also be made by coating near-ultraviolet (NUV) LEDs with a mixture of high-efficiency europium-based phosphors that emit red and blue, plus copper and aluminium-doped zinc sulfide (ZnS:Cu, Al) that emits green. This is a method analogous to the way fluorescent lamps work. This method is less efficient than blue LEDs with YAG:Ce phosphor, as the Stokes shift is larger, so more energy is converted to heat, but yields light with better spectral characteristics, which render color better. Due to the higher radiative output of the ultraviolet LEDs than of the blue ones, both methods offer comparable brightness. A concern is that UV light may leak from a malfunctioning light source and cause harm to human eyes or skin.

Other white LEDs

Another method used to produce experimental white light LEDs used no phosphors at all and was based on homoepitaxially grown zinc selenide (ZnSe) on a ZnSe substrate that simultaneously emitted blue light from its active region and yellow light from the substrate.[104]

A new style of wafers composed of gallium-nitride-on-silicon (GaN-on-Si) is being used to produce white LEDs using 200-mm silicon wafers. This avoids the typical costly sapphire substrate in relatively small 100- or 150-mm wafer sizes.[105] The sapphire apparatus must be coupled with a mirror-like collector to reflect light that would otherwise be wasted. It was predicted that since 2020, 40% of all GaN LEDs are made with GaN-on-Si. Manufacturing large sapphire material is difficult, while large silicon material is cheaper and more abundant. LED companies shifting from using sapphire to silicon should be a minimal investment.[106]

Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs)

In an organic light-emitting diode (OLED), the electroluminescent material composing the emissive layer of the diode is an organic compound. The organic material is electrically conductive due to the delocalization of pi electrons caused by conjugation over all or part of the molecule, and the material therefore functions as an organic semiconductor.[107] The organic materials can be small organic molecules in a crystalline phase, or polymers.[108]

The potential advantages of OLEDs include thin, low-cost displays with a low driving voltage, wide viewing angle, and high contrast and color gamut.[109] Polymer LEDs have the added benefit of printable and flexible displays.[110][111][112] OLEDs have been used to make visual displays for portable electronic devices such as cellphones, digital cameras, lighting and televisions.[108][109]

Types

LEDs are made in different packages for different applications. A single or a few LED junctions may be packed in one miniature device for use as an indicator or pilot lamp. An LED array may include controlling circuits within the same package, which may range from a simple resistor, blinking or color changing control, or an addressable controller for RGB devices. Higher-powered white-emitting devices will be mounted on heat sinks and will be used for illumination. Alphanumeric displays in dot matrix or bar formats are widely available. Special packages permit connection of LEDs to optical fibers for high-speed data communication links.

Miniature

These are mostly single-die LEDs used as indicators, and they come in various sizes from 2 mm to 8 mm, through-hole and surface mount packages.[113] Typical current ratings range from around 1 mA to above 20 mA. Multiple LED dies attached to a flexible backing tape form an LED strip light.

Common package shapes include round, with a domed or flat top, rectangular with a flat top (as used in bar-graph displays), and triangular or square with a flat top. The encapsulation may also be clear or tinted to improve contrast and viewing angle. Infrared devices may have a black tint to block visible light while passing infrared radiation.

Ultra-high-output LEDs are designed for viewing in direct sunlight

5 V and 12 V LEDs are ordinary miniature LEDs that have a series resistor for direct connection to a 5 V or 12 V supply.

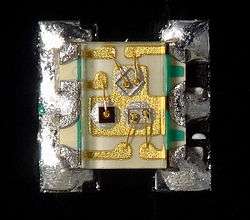

High-power

.jpg)

High-power LEDs (HP-LEDs) or high-output LEDs (HO-LEDs) can be driven at currents from hundreds of mA to more than an ampere, compared with the tens of mA for other LEDs. Some can emit over a thousand lumens.[114][115] LED power densities up to 300 W/cm2 have been achieved. Since overheating is destructive, the HP-LEDs must be mounted on a heat sink to allow for heat dissipation. If the heat from an HP-LED is not removed, the device fails in seconds. One HP-LED can often replace an incandescent bulb in a flashlight, or be set in an array to form a powerful LED lamp.

Some well-known HP-LEDs in this category are the Nichia 19 series, Lumileds Rebel Led, Osram Opto Semiconductors Golden Dragon, and Cree X-lamp. As of September 2009, some HP-LEDs manufactured by Cree now exceed 105 lm/W.[116]

Examples for Haitz's law—which predicts an exponential rise in light output and efficacy of LEDs over time—are the CREE XP-G series LED, which achieved 105 lm/W in 2009[116] and the Nichia 19 series with a typical efficacy of 140 lm/W, released in 2010.[117]

AC-driven

LEDs developed by Seoul Semiconductor can operate on AC power without a DC converter. For each half-cycle, part of the LED emits light and part is dark, and this is reversed during the next half-cycle. The efficacy of this type of HP-LED is typically 40 lm/W.[118] A large number of LED elements in series may be able to operate directly from line voltage. In 2009, Seoul Semiconductor released a high DC voltage LED, named as 'Acrich MJT', capable of being driven from AC power with a simple controlling circuit. The low-power dissipation of these LEDs affords them more flexibility than the original AC LED design.[119]

Application-specific variations

Flashing

Flashing LEDs are used as attention seeking indicators without requiring external electronics. Flashing LEDs resemble standard LEDs but they contain an integrated voltage regulator and a multivibrator circuit that causes the LED to flash with a typical period of one second. In diffused lens LEDs, this circuit is visible as a small black dot. Most flashing LEDs emit light of one color, but more sophisticated devices can flash between multiple colors and even fade through a color sequence using RGB color mixing.

Bi-color

Bi-color LEDs contain two different LED emitters in one case. There are two types of these. One type consists of two dies connected to the same two leads antiparallel to each other. Current flow in one direction emits one color, and current in the opposite direction emits the other color. The other type consists of two dies with separate leads for both dies and another lead for common anode or cathode so that they can be controlled independently. The most common bi-color combination is red/traditional green, however, other available combinations include amber/traditional green, red/pure green, red/blue, and blue/pure green.

RGB Tri-color

Tri-color LEDs contain three different LED emitters in one case. Each emitter is connected to a separate lead so they can be controlled independently. A four-lead arrangement is typical with one common lead (anode or cathode) and an additional lead for each color. Others, however, have only two leads (positive and negative) and have a built-in electronic controller.

RGB LEDs consist of one red, one green, and one blue LED.[120] By independently adjusting each of the three, RGB LEDs are capable of producing a wide color gamut. Unlike dedicated-color LEDs, however, these do not produce pure wavelengths. Modules may not be optimized for smooth color mixing.

Decorative-multicolor

Decorative-multicolor LEDs incorporate several emitters of different colors supplied by only two lead-out wires. Colors are switched internally by varying the supply voltage.

Alphanumeric

Alphanumeric LEDs are available in seven-segment, starburst, and dot-matrix format. Seven-segment displays handle all numbers and a limited set of letters. Starburst displays can display all letters. Dot-matrix displays typically use 5×7 pixels per character. Seven-segment LED displays were in widespread use in the 1970s and 1980s, but rising use of liquid crystal displays, with their lower power needs and greater display flexibility, has reduced the popularity of numeric and alphanumeric LED displays.

Digital RGB

Digital RGB addressable LEDs contain their own "smart" control electronics. In addition to power and ground, these provide connections for data-in, data-out, clock and sometimes a strobe signal. These are connected in a daisy chain. Data sent to the first LED of the chain can control the brightness and color of each LED independently of the others. They are used where a combination of maximum control and minimum visible electronics are needed such as strings for Christmas and LED matrices. Some even have refresh rates in the kHz range, allowing for basic video applications. These devices are known by their part number (WS2812 being common) or a brand name such as NeoPixel.

Filament

An LED filament consists of multiple LED chips connected in series on a common longitudinal substrate that forms a thin rod reminiscent of a traditional incandescent filament.[121] These are being used as a low-cost decorative alternative for traditional light bulbs that are being phased out in many countries. The filaments use a rather high voltage, allowing them to work efficiently with mains voltages. Often a simple rectifier and capacitive current limiting are employed to create a low-cost replacement for a traditional light bulb without the complexity of the low voltage, high current converter that single die LEDs need.[122] Usually, they are packaged in bulb similar to the lamps they were designed to replace, and filled with inert gas to remove heat efficiently.

Chip-on-board arrays

Surface-mounted LEDs are frequently produced in chip on board (COB) arrays, allowing better heat dissipation than with a single LED of comparable luminous output.[123] The LEDs can be arranged around a cylinder, and are called "corn cob lights" because of the rows of yellow LEDs.[124]

Considerations for use

Power sources

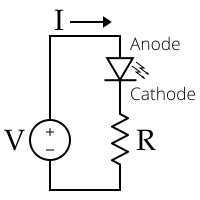

The current in an LED or other diodes rises exponentially with the applied voltage (see Shockley diode equation), so a small change in voltage can cause a large change in current. Current through the LED must be regulated by an external circuit such as a constant current source to prevent damage. Since most common power supplies are (nearly) constant-voltage sources, LED fixtures must include a power converter, or at least a current-limiting resistor. In some applications, the internal resistance of small batteries is sufficient to keep current within the LED rating.

Electrical polarity

Unlike a traditional incandescent lamp, an LED will light only when voltage is applied in the forward direction of the diode. No current flows and no light is emitted if voltage is applied in the reverse direction. If the reverse voltage exceeds the breakdown voltage, a large current flows and the LED will be damaged. If the reverse current is sufficiently limited to avoid damage, the reverse-conducting LED is a useful noise diode.

Safety and health

Certain blue LEDs and cool-white LEDs can exceed safe limits of the so-called blue-light hazard as defined in eye safety specifications such as "ANSI/IESNA RP-27.1–05: Recommended Practice for Photobiological Safety for Lamp and Lamp Systems".[125] One study showed no evidence of a risk in normal use at domestic illuminance,[126] and that caution is only needed for particular occupational situations or for specific populations.[127] In 2006, the International Electrotechnical Commission published IEC 62471 Photobiological safety of lamps and lamp systems, replacing the application of early laser-oriented standards for classification of LED sources.[128]

While LEDs have the advantage over fluorescent lamps, in that they do not contain mercury, they may contain other hazardous metals such as lead and arsenic.[129]

In 2016 the American Medical Association (AMA) issued a statement concerning the possible adverse influence of blueish street lighting on the sleep-wake cycle of city-dwellers. Industry critics claim exposure levels are not high enough to have a noticeable effect.[130]

Advantages

- Efficiency: LEDs emit more lumens per watt than incandescent light bulbs.[131] The efficiency of LED lighting fixtures is not affected by shape and size, unlike fluorescent light bulbs or tubes.

- Color: LEDs can emit light of an intended color without using any color filters as traditional lighting methods need. This is more efficient and can lower initial costs.

- Size: LEDs can be very small (smaller than 2 mm2[132]) and are easily attached to printed circuit boards.

- Warmup time: LEDs light up very quickly. A typical red indicator LED achieves full brightness in under a microsecond.[133] LEDs used in communications devices can have even faster response times.

- Cycling: LEDs are ideal for uses subject to frequent on-off cycling, unlike incandescent and fluorescent lamps that fail faster when cycled often, or high-intensity discharge lamps (HID lamps) that require a long time before restarting.

- Dimming: LEDs can very easily be dimmed either by pulse-width modulation or lowering the forward current.[134] This pulse-width modulation is why LED lights, particularly headlights on cars, when viewed on camera or by some people, seem to flash or flicker. This is a type of stroboscopic effect.

- Cool light: In contrast to most light sources, LEDs radiate very little heat in the form of IR that can cause damage to sensitive objects or fabrics. Wasted energy is dispersed as heat through the base of the LED.

- Slow failure: LEDs mainly fail by dimming over time, rather than the abrupt failure of incandescent bulbs.[135]

- Lifetime: LEDs can have a relatively long useful life. One report estimates 35,000 to 50,000 hours of useful life, though time to complete failure may be shorter or longer.[136] Fluorescent tubes typically are rated at about 10,000 to 25,000 hours, depending partly on the conditions of use, and incandescent light bulbs at 1,000 to 2,000 hours. Several DOE demonstrations have shown that reduced maintenance costs from this extended lifetime, rather than energy savings, is the primary factor in determining the payback period for an LED product.[137]

- Shock resistance: LEDs, being solid-state components, are difficult to damage with external shock, unlike fluorescent and incandescent bulbs, which are fragile.[138]

- Focus: The solid package of the LED can be designed to focus its light. Incandescent and fluorescent sources often require an external reflector to collect light and direct it in a usable manner. For larger LED packages total internal reflection (TIR) lenses are often used to the same effect. However, when large quantities of light are needed many light sources are usually deployed, which are difficult to focus or collimate towards the same target.

Disadvantages

- Temperature dependence: LED performance largely depends on the ambient temperature of the operating environment – or thermal management properties. Overdriving an LED in high ambient temperatures may result in overheating the LED package, eventually leading to device failure. An adequate heat sink is needed to maintain long life. This is especially important in automotive, medical, and military uses where devices must operate over a wide range of temperatures, and require low failure rates.

- Voltage sensitivity: LEDs must be supplied with a voltage above their threshold voltage and a current below their rating. Current and lifetime change greatly with a small change in applied voltage. They thus require a current-regulated supply (usually just a series resistor for indicator LEDs).[139]

- Color rendition: Most cool-white LEDs have spectra that differ significantly from a black body radiator like the sun or an incandescent light. The spike at 460 nm and dip at 500 nm can make the color of objects appear differently under cool-white LED illumination than sunlight or incandescent sources, due to metamerism,[140] red surfaces being rendered particularly poorly by typical phosphor-based cool-white LEDs. The same is true with green surfaces. The quality of color rendition of an LED is measured by the Color Rendering Index (CRI).

- Area light source: Single LEDs do not approximate a point source of light giving a spherical light distribution, but rather a lambertian distribution. So, LEDs are difficult to apply to uses needing a spherical light field; however, different fields of light can be manipulated by the application of different optics or "lenses". LEDs cannot provide divergence below a few degrees.[141]

- Light pollution: Because white LEDs emit more short wavelength light than sources such as high-pressure sodium vapor lamps, the increased blue and green sensitivity of scotopic vision means that white LEDs used in outdoor lighting cause substantially more sky glow.[119]

- Efficiency droop: The efficiency of LEDs decreases as the electric current increases. Heating also increases with higher currents, which compromises LED lifetime. These effects put practical limits on the current through an LED in high power applications.[142]

- Impact on wildlife: LEDs are much more attractive to insects than sodium-vapor lights, so much so that there has been speculative concern about the possibility of disruption to food webs.[143][144] LED lighting near beaches, particularly intense blue and white colors, can disorient turtle hatchlings and make them wander inland instead.[145] The use of "Turtle-safe lighting" LEDs that emit only at narrow portions of the visible spectrum is encouraged by conservancy groups in order to reduce harm.[146]

- Use in winter conditions: Since they do not give off much heat in comparison to incandescent lights, LED lights used for traffic control can have snow obscuring them, leading to accidents.[147][148]

- Thermal runaway: Parallel strings of LEDs will not share current evenly due to the manufacturing tolerances in their forward voltage. Running two or more strings from a single current source may result in LED failure as the devices warm up. If forward voltage binning is not possible, a circuit is required to ensure even distribution of current between parallel strands.[149]

Applications

LED uses fall into four major categories:

- Visual signals where light goes more or less directly from the source to the human eye, to convey a message or meaning

- Illumination where light is reflected from objects to give visual response of these objects

- Measuring and interacting with processes involving no human vision[150]

- Narrow band light sensors where LEDs operate in a reverse-bias mode and respond to incident light, instead of emitting light[151][152][153][154]

Indicators and signs

The low energy consumption, low maintenance and small size of LEDs has led to uses as status indicators and displays on a variety of equipment and installations. Large-area LED displays are used as stadium displays, dynamic decorative displays, and dynamic message signs on freeways. Thin, lightweight message displays are used at airports and railway stations, and as destination displays for trains, buses, trams, and ferries.

One-color light is well suited for traffic lights and signals, exit signs, emergency vehicle lighting, ships' navigation lights, and LED-based Christmas lights

Because of their long life, fast switching times, and visibility in broad daylight due to their high output and focus, LEDs have been used in automotive brake lights and turn signals. The use in brakes improves safety, due to a great reduction in the time needed to light fully, or faster rise time, about 0.1 second faster than an incandescent bulb. This gives drivers behind more time to react. In a dual intensity circuit (rear markers and brakes) if the LEDs are not pulsed at a fast enough frequency, they can create a phantom array, where ghost images of the LED appear if the eyes quickly scan across the array. White LED headlamps are beginning to appear. Using LEDs has styling advantages because LEDs can form much thinner lights than incandescent lamps with parabolic reflectors.

Due to the relative cheapness of low output LEDs, they are also used in many temporary uses such as glowsticks, throwies, and the photonic textile Lumalive. Artists have also used LEDs for LED art.

Lighting

With the development of high-efficiency and high-power LEDs, it has become possible to use LEDs in lighting and illumination. To encourage the shift to LED lamps and other high-efficiency lighting,in 2008 the US Department of Energy created the L Prize competition. The Philips Lighting North America LED bulb won the first competition on August 3, 2011, after successfully completing 18 months of intensive field, lab, and product testing.[155]

Efficient lighting is needed for sustainable architecture. As of 2011, some LED bulbs provide up to 150 lm/W and even inexpensive low-end models typically exceed 50 lm/W, so that a 6-watt LED could achieve the same results as a standard 40-watt incandescent bulb. The lower heat output of LEDs also reduces demand on air conditioning systems. Worldwide, LEDs are rapidly adopted to displace less effective sources such as incandescent lamps and CFLs and reduce electrical energy consumption and its associated emissions. Solar powered LEDs are used as street lights and in architectural lighting.

The mechanical robustness and long lifetime are used in automotive lighting on cars, motorcycles, and bicycle lights. LED street lights are employed on poles and in parking garages. In 2007, the Italian village of Torraca was the first place to convert its street lighting to LEDs.[156]

Cabin lighting on recent Airbus and Boeing jetliners uses LED lighting. LEDs are also being used in airport and heliport lighting. LED airport fixtures currently include medium-intensity runway lights, runway centerline lights, taxiway centerline and edge lights, guidance signs, and obstruction lighting.

LEDs are also used as a light source for DLP projectors, and to backlight LCD televisions (referred to as LED TVs) and laptop displays. RGB LEDs raise the color gamut by as much as 45%. Screens for TV and computer displays can be made thinner using LEDs for backlighting.[157]

LEDs are small, durable and need little power, so they are used in handheld devices such as flashlights. LED strobe lights or camera flashes operate at a safe, low voltage, instead of the 250+ volts commonly found in xenon flashlamp-based lighting. This is especially useful in cameras on mobile phones, where space is at a premium and bulky voltage-raising circuitry is undesirable.

LEDs are used for infrared illumination in night vision uses including security cameras. A ring of LEDs around a video camera, aimed forward into a retroreflective background, allows chroma keying in video productions.

LEDs are used in mining operations, as cap lamps to provide light for miners. Research has been done to improve LEDs for mining, to reduce glare and to increase illumination, reducing risk of injury to the miners.[158]

LEDs are increasingly finding uses in medical and educational applications, for example as mood enhancement.[159] NASA has even sponsored research for the use of LEDs to promote health for astronauts.[160]

Data communication and other signalling

Light can be used to transmit data and analog signals. For example, lighting white LEDs can be used in systems assisting people to navigate in closed spaces while searching necessary rooms or objects.[161]

Assistive listening devices in many theaters and similar spaces use arrays of infrared LEDs to send sound to listeners' receivers. Light-emitting diodes (as well as semiconductor lasers) are used to send data over many types of fiber optic cable, from digital audio over TOSLINK cables to the very high bandwidth fiber links that form the Internet backbone. For some time, computers were commonly equipped with IrDA interfaces, which allowed them to send and receive data to nearby machines via infrared.

Because LEDs can cycle on and off millions of times per second, very high data bandwidth can be achieved.[162]

Machine vision systems

Machine vision systems often require bright and homogeneous illumination, so features of interest are easier to process. LEDs are often used.

Barcode scanners are the most common example of machine vision applications, and many of those scanners use red LEDs instead of lasers. Optical computer mice use LEDs as a light source for the miniature camera within the mouse.

LEDs are useful for machine vision because they provide a compact, reliable source of light. LED lamps can be turned on and off to suit the needs of the vision system, and the shape of the beam produced can be tailored to match the system's requirements.

Biological detection

The discovery of radiative recombination in Aluminum Gallium Nitride (AlGaN) alloys by U.S. Army Research Laboratory (ARL) led to the conceptualization of UV light emitting diodes (LEDs) to be incorporated in light induced fluorescence sensors used for biological agent detection.[163][164][165] In 2004, the Edgewood Chemical Biological Center (ECBC) initiated the effort to create a biological detector named TAC-BIO. The program capitalized on Semiconductor UV Optical Sources (SUVOS) developed by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).[165]

UV induced fluorescence is one of the most robust techniques used for rapid real time detection of biological aerosols.[165] The first UV sensors were lasers lacking in-field-use practicality. In order to address this, DARPA incorporated SUVOS technology to create a low cost, small, lightweight, low power device. The TAC-BIO detector's response time was one minute from when it sensed a biological agent. It was also demonstrated that the detector could be operated unattended indoors and outdoors for weeks at a time.[165]

Aerosolized biological particles will fluoresce and scatter light under a UV light beam. Observed fluorescence is dependent on the applied wavelength and the biochemical fluorophores within the biological agent. UV induced fluorescence offers a rapid, accurate, efficient and logistically practical way for biological agent detection. This is because the use of UV fluorescence is reagent less, or a process that does not require an added chemical to produce a reaction, with no consumables, or produces no chemical byproducts.[165]

Additionally, TAC-BIO can reliably discriminate between threat and non-threat aerosols. It was claimed to be sensitive enough to detect low concentrations, but not so sensitive that it would cause false positives. The particle counting algorithm used in the device converted raw data into information by counting the photon pulses per unit of time from the fluorescence and scattering detectors, and comparing the value to a set threshold.[166]

The original TAC-BIO was introduced in 2010, while the second generation TAC-BIO GEN II, was designed in 2015 to be more cost efficient as plastic parts were used. Its small, light-weight design allows it to be mounted to vehicles, robots, and unmanned aerial vehicles. The second generation device could also be utilized as an environmental detector to monitor air quality in hospitals, airplanes, or even in households to detect fungus and mold.[167][168]

Other applications

The light from LEDs can be modulated very quickly so they are used extensively in optical fiber and free space optics communications. This includes remote controls, such as for television sets, where infrared LEDs are often used. Opto-isolators use an LED combined with a photodiode or phototransistor to provide a signal path with electrical isolation between two circuits. This is especially useful in medical equipment where the signals from a low-voltage sensor circuit (usually battery-powered) in contact with a living organism must be electrically isolated from any possible electrical failure in a recording or monitoring device operating at potentially dangerous voltages. An optoisolator also lets information be transferred between circuits that don't share a common ground potential.

Many sensor systems rely on light as the signal source. LEDs are often ideal as a light source due to the requirements of the sensors. The Nintendo Wii's sensor bar uses infrared LEDs. Pulse oximeters use them for measuring oxygen saturation. Some flatbed scanners use arrays of RGB LEDs rather than the typical cold-cathode fluorescent lamp as the light source. Having independent control of three illuminated colors allows the scanner to calibrate itself for more accurate color balance, and there is no need for warm-up. Further, its sensors only need be monochromatic, since at any one time the page being scanned is only lit by one color of light.

Since LEDs can also be used as photodiodes, they can be used for both photo emission and detection. This could be used, for example, in a touchscreen that registers reflected light from a finger or stylus.[169] Many materials and biological systems are sensitive to, or dependent on, light. Grow lights use LEDs to increase photosynthesis in plants,[170] and bacteria and viruses can be removed from water and other substances using UV LEDs for sterilization.[90]

Deep UV LEDs, with a spectra range 247 nm to 386 nm, have other applications, such as water/air purification, surface disinfection, epoxy curing, free-space nonline-of-sight communication, high performance liquid chromatography, UV curing and printing, phototherapy, medical/ analytical instrumentation, and DNA absorption.[164][171]

LEDs have also been used as a medium-quality voltage reference in electronic circuits. The forward voltage drop (about 1.7 V for a red LED or 1.2V for an infrared) can be used instead of a Zener diode in low-voltage regulators. Red LEDs have the flattest I/V curve above the knee. Nitride-based LEDs have a fairly steep I/V curve and are useless for this purpose. Although LED forward voltage is far more current-dependent than a Zener diode, Zener diodes with breakdown voltages below 3 V are not widely available.

The progressive miniaturization of low-voltage lighting technology, such as LEDs and OLEDs, suitable to incorporate into low-thickness materials has fostered experimentation in combining light sources and wall covering surfaces for interior walls in the form of LED wallpaper.

A large LED display behind a disc jockey

A large LED display behind a disc jockey Seven-segment display that can display four digits and points

Seven-segment display that can display four digits and points LED panel light source used in an experiment on plant growth. The findings of such experiments may be used to grow food in space on long duration missions.

LED panel light source used in an experiment on plant growth. The findings of such experiments may be used to grow food in space on long duration missions.

Research and development

Key challenges

LEDs require optimized efficiency to hinge on ongoing improvements such as phosphor materials and quantum dots.[172][173]

The process of down-conversion (the method by which materials convert more-energetic photons to different, less energetic colors) also needs improvement. For example, the red phosphors that are used today are thermally sensitive and need to be improved in that aspect so that they do not color shift and experience efficiency drop-off with temperature. Red phosphors could also benefit from a narrower spectral width to emit more lumens and becoming more efficient at converting photons.[174]

In addition, work remains to be done in the realms of current efficiency droop, color shift, system reliability, light distribution, dimming, thermal management, and power supply performance.[172]

Potential technology

Perovskite LEDs (PLEDs)

A new family of LEDs are based on the semiconductors called perovskites. In 2018, less than four years after their discovery, the ability of perovskite LEDs (PLEDs) to produce light from electrons already rivaled those of the best performing OLEDs.[175] They have a potential for cost-effectiveness as they can be processed from solution, a low-cost and low-tech method, which might allow perovskite-based devices that have large areas to be made with extremely low cost. Their efficiency is superior by eliminating non-radiative losses, in other words, elimination of recombination pathways that do not produce photons; or by solving outcoupling problem (prevalent for thin-film LEDs) or balancing charge carrier injection to increase the EQE (external quantum efficiency). The most up-to-date PLED devices have broken the performance barrier by shooting the EQE above 20%.[176]

In 2018, Cao et al. and Lin et al. independently published two papers on developing perovskite LEDs with EQE greater than 20%, which made these two papers a mile-stone in PLED development. Their device have similar planar structure, i.e. the active layer (perovskite) is sandwiched between two electrodes. To achieve a high EQE, they not only reduced non-radiative recombination, but also utilized their own, subtly different methods to improve the EQE.[176]

In Cao and his colleagues' work, they targeted to solve the outcoupling problem, which is that the optical physics of thin-film LEDs causes the majority of light generated by the semiconductor to be trapped in the device.[177] To achieve this goal, they demonstrated that solution-processed perovskites can spontaneously form submicrometre-scale crystal platelets, which can efficiently extract light from the device. These perovskites are formed simply by introducing amino-acif additives into the perovskite precursor solutions. In addition, their method is able to passivate perovskite surface defects and reduce nonradiative recombination. Therefore, by improving the light outcoupling and reducing nonradiative losses, Cao and his colleagues successfully achieved PLED with EQE up to 20.7%.[178]

In Lin and his colleague's work, however, they used a different approach to generate high EQE. Instead of modifying the microstructure of perovskite layer, they chose to adopt a new strategy for managing the compositional distribution in the device——an approach that simultaneously provides high luminescence and balanced charge injection. In other words, they still used flat emissive layer, but tried to optimize the balance of electrons and holes injected into the perovskite, so as to make the most efficient use of the charge carriers. Moreover, in the perovskite layer, the crystals are perfectly enclosed by MABr additive (where MA is CH3NH3). The MABr shell passivates the nonradiative defects that would otherwise be present perovskite crystals, resulting in reduction of the nonradiative recombination. Therefore, by balancing charge injection and decreasing nonradiative losses, Lin and his colleagues developed PLED with EQE up to 20.3%.[179]

Two-way LEDs

Devices called "nanorods" are a form of LEDs that can also detect and absorb light. They consist of a quantum dot directly contacting two semiconductor materials (instead of just one as in a traditional LED). One semiconductor allows movement of positive charge and one allows movement of negative charge. They can emit light, sense light, and collect energy. The nanorod gathers electrons while the quantum dot shell gathers positive charges so the dot emits light. When the voltage is switched the opposite process occurs and the dot absorbs light. By 2017 the only color developed was red.[180]

See also

References

- "HJ Round was a pioneer in the development of the LED". www.myledpassion.com.

- "The life and times of the LED — a 100-year history" (PDF). The Optoelectronics Research Centre, University of Southampton. April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2012. Retrieved September 4, 2012.

- US Patent 3293513, "Semiconductor Radiant Diode", James R. Biard and Gary Pittman, Filed on Aug. 8th, 1962, Issued on Dec. 20th, 1966.

- "Inventor of Long-Lasting, Low-Heat Light Source Awarded $500,000 Lemelson-MIT Prize for Invention". Washington, D.C. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. April 21, 2004. Archived from the original on October 9, 2011. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- Edwards, Kimberly D. "Light Emitting Diodes" (PDF). University of California at Irvine. p. 2. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- Lighting Research Center. "How is white light made with LEDs?". Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Retrieved January 12, 2019.

- Okon, Thomas M.; Biard, James R. (2015). "The First Practical LED" (PDF). EdisonTechCenter.org. Edison Tech Center. Retrieved February 2, 2016.

- Peláez, E. A; Villegas, E. R (2007). LED power reduction trade-offs for ambulatory pulse oximetry. 2007 29th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. 2007. pp. 2296–9. doi:10.1109/IEMBS.2007.4352784. ISBN 978-1-4244-0787-3. PMID 18002450.

- "LED Basics | Department of Energy". www.energy.gov. Retrieved October 22, 2018.

- "LED Spectral Distribution". optiwave.com. July 25, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Round, H. J. (1907). "A note on carborundum". Electrical World. 19: 309.

- Margolin J. "The Road to the Transistor". jmargolin.com.

- Losev, O. V. (1927). "Светящийся карборундовый детектор и детектирование с кристаллами" [Luminous carborundum detector and detection with crystals]. Телеграфия и Телефония без Проводов [Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony] (in Russian). 5 (44): 485–494. English translation: Losev, O. V. (November 1928). "Luminous carborundum detector and detection effect and oscillations with crystals". Philosophical Magazine. 7th series. 5 (39): 1024–1044. doi:10.1080/14786441108564683.

- Zheludev, N. (2007). "The life and times of the LED: a 100-year history" (PDF). Nature Photonics. 1 (4): 189–192. Bibcode:2007NaPho...1..189Z. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2007.34. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2011. Retrieved April 11, 2007.

- Lee, Thomas H. (2004). The design of CMOS radio-frequency integrated circuits. Cambridge University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-521-83539-8.

- Destriau, G. (1936). "Recherches sur les scintillations des sulfures de zinc aux rayons". Journal de Chimie Physique. 33: 587–625. doi:10.1051/jcp/1936330587.

- McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Physics: electroluminescence. (n.d.) McGraw-Hill Concise Encyclopedia of Physics. (2002).

- "Brief history of LEDs" (PDF).

- Lehovec, K; Accardo, C. A; Jamgochian, E (1951). "Injected Light Emission of Silicon Carbide Crystals". Physical Review. 83 (3): 603–607. Bibcode:1951PhRv...83..603L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.83.603. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014.

- Lehovec, K; Accardo, C. A; Jamgochian, E (1953). "Injected Light Emission of Silicon Carbide Crystals". Physical Review. 89 (1): 20–25. Bibcode:1953PhRv...89...20L. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.89.20.

- "Rubin Braunstein". UCLA. Archived from the original on March 11, 2011. Retrieved January 24, 2012.

- Braunstein, Rubin (1955). "Radiative Transitions in Semiconductors". Physical Review. 99 (6): 1892–1893. Bibcode:1955PhRv...99.1892B. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.99.1892.

- Kroemer, Herbert (September 16, 2013). "The Double-Heterostructure Concept: How It Got Started". Proceedings of the IEEE. 101 (10): 2183–2187. doi:10.1109/JPROC.2013.2274914.

- Matzen, W. T. ed. (March 1963) "Semiconductor Single-Crystal Circuit Development," Texas Instruments Inc., Contract No. AF33(616)-6600, Rept. No ASD-TDR-63-281.

- Carr, W. N.; G. E. Pittman (November 1963). "One-watt GaAs p-n junction infrared source". Applied Physics Letters. 3 (10): 173–175. Bibcode:1963ApPhL...3..173C. doi:10.1063/1.1753837.

- Kubetz, Rick (May 4, 2012). "Nick Holonyak, Jr., six decades in pursuit of light". University of Illinois. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- Holonyak Nick; Bevacqua, S. F. (December 1962). "Coherent (Visible) Light Emission from Ga(As1−x Px) Junctions". Applied Physics Letters. 1 (4): 82. Bibcode:1962ApPhL...1...82H. doi:10.1063/1.1753706. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- Wolinsky, Howard (February 5, 2005). "U. of I.'s Holonyak out to take some of Edison's luster". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on March 28, 2006. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- Perry, T. S. (1995). "M. George Craford [biography]". IEEE Spectrum. 32 (2): 52–55. doi:10.1109/6.343989.

- "Brief Biography — Holonyak, Craford, Dupuis" (PDF). Technology Administration. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 9, 2007. Retrieved May 30, 2007.

- Pearsall, T. P.; Miller, B. I.; Capik, R. J.; Bachmann, K. J. (1976). "Efficient, Lattice-matched, Double Heterostructure LEDs at 1.1 mm from GaxIn1−xAsyP1−y by Liquid-phase Epitaxy". Appl. Phys. Lett. 28 (9): 499. Bibcode:1976ApPhL..28..499P. doi:10.1063/1.88831.

- Rostky, George (March 1997). "LEDs cast Monsanto in Unfamiliar Role". Electronic Engineering Times (EETimes) (944).

- Schubert, E. Fred (2003). "1". Light-Emitting Diodes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-8194-3956-7.

- Borden, Howard C.; Pighini, Gerald P. (February 1969). "Solid-State Displays" (PDF). Hewlett-Packard Journal: 2–12.

- House, Charles H.; Price, Raymond L. (2009). The HP Phenomenon: Innovation and Business Transformation. Stanford University Press. pp. 110–1. ISBN 9780804772617.

- Kramer, Bernhard (2003). Advances in Solid State Physics. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 40. ISBN 9783540401506.

- "Hewlett-Packard 5082-7000". The Vintage Technology Association. Retrieved August 15, 2019.

- Bassett, Ross Knox (2007). To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 328. ISBN 9780801886393.

- Annual Report (PDF). Fairchild Camera and Instrument Corporation. 1969. p. 6.

- "Solid State Technology". Solid State Technology. Cowan Publishing Corporation. 15: 79.

Dr. Atalla was general manager of the Microwave & Optoelectronics division from its inception in May 1969 until November 1971 when it was incorporated into the Semiconductor Components Group.

- "Laser Focus with Fiberoptic Communications". Laser Focus with Fiberoptic Communications. Advanced Technology Publication. 7: 28. 1971.

Its chief, John Atalla — Greene's predecessor at Hewlett-Packard — sees early applications for LEDs in small displays, principally for indicator lights. Because of their compatibility with integrated circuits, these light emitters can be valuable in fault detection. “Reliability has already been demonstrated beyond any doubt,” Atalla continues. “No special power supplies are required. Design takes no time, you just put the diode in. So introduction becomes strictly an economic question." Bright Outlook for Optical Readers Atalla is particularly sanguine about applications of diodes in high-volume optical readers.

- US 3025589, "Method of Manufacturing Semiconductor Devices", issued Mar 20, 1962

- Patent number: 3025589 Retrieved May 17, 2013

- Lojek, Bo (2007). History of Semiconductor Engineering. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 120& 321–323. ISBN 9783540342588.

- Bassett, Ross Knox (2007). To the Digital Age: Research Labs, Start-up Companies, and the Rise of MOS Technology. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 46. ISBN 9780801886393.

- Bausch, Jeffrey (December 2011). "The Long History of Light Emitting Diodes". Hearst Business Communications.

- Park, S. -I.; Xiong, Y.; Kim, R. -H.; Elvikis, P.; Meitl, M.; Kim, D. -H.; Wu, J.; Yoon, J.; Yu, C. -J.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Y.; Hwang, K. -C.; Ferreira, P.; Li, X.; Choquette, K.; Rogers, J. A. (2009). "Printed Assemblies of Inorganic Light-Emitting Diodes for Deformable and Semitransparent Displays" (PDF). Science. 325 (5943): 977–981. Bibcode:2009Sci...325..977P. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.660.3338. doi:10.1126/science.1175690. PMID 19696346. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 24, 2015.

- "Nobel Shocker: RCA Had the First Blue LED in 1972". IEEE Spectrum. October 9, 2014

- "Oregon tech CEO says Nobel Prize in Physics overlooks the actual inventors". The Oregonian. October 16, 2014

- Schubert, E. Fred (2006) Light-emitting diodes 2nd ed., Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-86538-7 pp. 16–17

- Maruska, H. (2005). "A Brief History of GaN Blue Light-Emitting Diodes". LIGHTimes Online – LED Industry News. Archived June 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Major Business and Product Milestones. Cree.com. Retrieved on March 16, 2012. Archived April 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Edmond, John A.; Kong, Hua-Shuang; Carter, Calvin H. (April 1, 1993). "Blue LEDs, UV photodiodes and high-temperature rectifiers in 6H-SiC". Physica B: Condensed Matter. 185 (1): 453–460. Bibcode:1993PhyB..185..453E. doi:10.1016/0921-4526(93)90277-D. ISSN 0921-4526.

- "History & Milestones". Cree.com. Cree. Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- "GaN-based blue light emitting device development by Akasaki and Amano" (PDF). Takeda Award 2002 Achievement Facts Sheet. The Takeda Foundation. April 5, 2002. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- Moustakas, Theodore D. U.S. Patent 5,686,738A "Highly insulating monocrystalline gallium nitride thin films " Issue date: Mar 18, 1991

- Nakamura, S.; Mukai, T.; Senoh, M. (1994). "Candela-Class High-Brightness InGaN/AlGaN Double-Heterostructure Blue-Light-Emitting-Diodes". Appl. Phys. Lett. 64 (13): 1687. Bibcode:1994ApPhL..64.1687N. doi:10.1063/1.111832.

- Nakamura, Shuji. "Development of the Blue Light-Emitting Diode". SPIE Newsroom. Retrieved September 28, 2015.

- Iwasa, Naruhito; Mukai, Takashi and Nakamura, Shuji U.S. Patent 5,578,839 "Light-emitting gallium nitride-based compound semiconductor device" Issue date: November 26, 1996

- 2006 Millennium technology prize awarded to UCSB's Shuji Nakamura. Ia.ucsb.edu (June 15, 2006). Retrieved on August 3, 2019.

- Overbye, Dennis (October 7, 2014). "Nobel Prize in Physics". The New York Times.

- Brown, Joel (December 7, 2015). "BU Wins $13 Million in Patent Infringement Suit". BU Today. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- Dadgar, A.; Alam, A.; Riemann, T.; Bläsing, J.; Diez, A.; Poschenrieder, M.; Strassburg, M.; Heuken, M.; Christen, J.; Krost, A. (2001). "Crack-Free InGaN/GaN Light Emitters on Si(111)". Physica Status Solidi A. 188: 155–158. doi:10.1002/1521-396X(200111)188:1<155::AID-PSSA155>3.0.CO;2-P.

- Dadgar, A.; Poschenrieder, M.; BläSing, J.; Fehse, K.; Diez, A.; Krost, A. (2002). "Thick, crack-free blue light-emitting diodes on Si(111) using low-temperature AlN interlayers and in situ Si\sub x]N\sub y] masking". Applied Physics Letters. 80 (20): 3670. Bibcode:2002ApPhL..80.3670D. doi:10.1063/1.1479455.

- "Success in research: First gallium-nitride LED chips on silicon in pilot stage" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 15, 2012. Retrieved 2012-09-15.. www.osram.de, January 12, 2012.

- Lester, Steve (2014) Role of Substrate Choice on LED Packaging. Toshiba America Electronic Components.

- GaN on Silicon — Cambridge Centre for Gallium Nitride. Gan.msm.cam.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Bush, Steve. (2016-06-30) Toshiba gets out of GaN-on-Si leds. Electronicsweekly.com. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Nunoue, Shin-ya; Hikosaka, Toshiki; Yoshida, Hisashi; Tajima, Jumpei; Kimura, Shigeya; Sugiyama, Naoharu; Tachibana, Koichi; Shioda, Tomonari; Sato, Taisuke; Muramoto, Eiji; Onomura, Masaaki (2013). "LED manufacturing issues concerning gallium nitride-on-silicon (GaN-on-Si) technology and wafer scale up challenges". 2013 IEEE International Electron Devices Meeting. pp. 13.2.1–13.2.4. doi:10.1109/IEDM.2013.6724622. ISBN 978-1-4799-2306-9.

- Wright, Maury (2 May 2016) Samsung's Tarn reports progress in CSP and GaN-on-Si LEDs. LEDs Magazine.

- Increasing The Competitiveness Of The GaN-on-silicon LED. compoundsemiconductor.net (30 March 2016).

- Samsung To Focus on Silicon-based LED Chip Technology in 2015. LED Inside (17 March 2015).

- Keeping, Steven. (2013-01-15) Material and Manufacturing Improvements. DigiKey. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Keeping, Steven. (2014-12-09) Manufacturers Shift Attention to Light Quality to Further LED Market Share Gains. DigiKey. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Keeping, Steven. (2013-09-24) Will Silicon Substrates Push LED Lighting. DigiKey. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Keeping, Steven. (2015-03-24) Improved Silicon-Substrate LEDs Address High Solid-State Lighting Costs. DigiKey. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Development of the Nano-Imprint Equipment ST50S-LED for High-Brightness LED. Toshiba Machine (2011-05-18). Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- The use of sapphire in mobile device and LED industries: Part 2 | Solid State Technology. Electroiq.com (2017-09-26). Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Epitaxy. Applied Materials. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- "Haitz's law". Nature Photonics. 1 (1): 23. 2007. Bibcode:2007NaPho...1...23.. doi:10.1038/nphoton.2006.78.

- Morris, Nick (June 1, 2006). "LED there be light, Nick Morris predicts a bright future for LEDs". Electrooptics.com.

- "The LED Illumination Revolution". Forbes. February 27, 2008.

- Press Release, Official Nobel Prize website, 7 October 2014

- Cree First to Break 300 Lumens-Per-Watt Barrier. Cree.com (2014-03-26). Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- LM301B | SAMSUNG LED | Samsung LED Global Website. Samsung.com. Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- Samsung Achieves 220 Lumens per Watt with New Mid-Power LED Package. Samsung.com (2017-06-16). Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- LED breakthrough promises ultra efficient luminaires | Lux Magazine. Luxreview.com (2018-01-19). Retrieved on 2018-07-31.

- LED bulb efficiency expected to continue improving as cost declines. U.S. Energy Information Administration (March 19, 2014)

- Cooke, Mike (April–May 2010). "Going Deep for UV Sterilization LEDs" (PDF). Semiconductor Today. 5 (3): 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2013.

- Mori, M.; Hamamoto, A.; Takahashi, A.; Nakano, M.; Wakikawa, N.; Tachibana, S.; Ikehara, T.; Nakaya, Y.; Akutagawa, M.; Kinouchi, Y. (2007). "Development of a new water sterilization device with a 365 nm UV-LED". Medical & Biological Engineering & Computing. 45 (12): 1237–1241. doi:10.1007/s11517-007-0263-1. PMID 17978842.

- Taniyasu, Y.; Kasu, M.; Makimoto, T. (2006). "An aluminium nitride light-emitting diode with a wavelength of 210 nanometres". Nature. 441 (7091): 325–328. Bibcode:2006Natur.441..325T. doi:10.1038/nature04760. PMID 16710416.

- Kubota, Y.; Watanabe, K.; Tsuda, O.; Taniguchi, T. (2007). "Deep Ultraviolet Light-Emitting Hexagonal Boron Nitride Synthesized at Atmospheric Pressure". Science. 317 (5840): 932–934. Bibcode:2007Sci...317..932K. doi:10.1126/science.1144216. PMID 17702939.

- Watanabe, K.; Taniguchi, T.; Kanda, H. (2004). "Direct-bandgap properties and evidence for ultraviolet lasing of hexagonal boron nitride single crystal". Nature Materials. 3 (6): 404–409. Bibcode:2004NatMa...3..404W. doi:10.1038/nmat1134. PMID 15156198.

- Koizumi, S.; Watanabe, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Kanda, H. (2001). "Ultraviolet Emission from a Diamond pn Junction". Science. 292 (5523): 1899–1901. Bibcode:2001Sci...292.1899K. doi:10.1126/science.1060258. PMID 11397942.

- "Seeing Red with PFS Phosphor".

- "GE Lighting manufactures PFS red phosphor for LED display backlight applications". March 31, 2015.

- "GE TriGain® Phosphor Technology | GE".