Marie Curie

Marie Skłodowska Curie (/ˈkjʊəri/ KEWR-ee;[3] French: [kyʁi]; Polish: [kʲiˈri]), born Maria Salomea Skłodowska (Polish: [ˈmarja salɔˈmɛa skwɔˈdɔfska]; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), was a Polish and naturalized-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

Marie Curie | |

|---|---|

circa 1920 | |

| Born | Maria Salomea Skłodowska 7 November 1867 |

| Died | 4 July 1934 (aged 66) Passy, Haute-Savoie, France |

| Cause of death | Aplastic anemia from exposure to radiation |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for | |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics, chemistry |

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Recherches sur les substances radioactives (Research on Radioactive Substances) |

| Doctoral advisor | Gabriel Lippmann |

| Doctoral students | |

| Signature | |

| Notes | |

She is the only person to win a Nobel Prize in two sciences. | |

As part of the Curie family legacy of five Nobel Prizes, she was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person and the only woman to win the Nobel Prize twice, and the only person to win the Nobel Prize in two scientific fields. She was also the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris.[4]

She was born in Warsaw, in what was then the Kingdom of Poland, part of the Russian Empire. She studied at Warsaw's clandestine Flying University and began her practical scientific training in Warsaw. In 1891, aged 24, she followed her elder sister Bronisława to study in Paris, where she earned her higher degrees and conducted her subsequent scientific work.

She shared the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics with her husband Pierre Curie and physicist Henri Becquerel, for their pioneering work developing the theory of "radioactivity" (a term she coined).[5][6] Using techniques she invented for isolating radioactive isotopes, she won the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for the discovery of two elements, polonium and radium.

Under her direction, the world's first studies were conducted into the treatment of neoplasms using radioactive isotopes. She founded the Curie Institutes in Paris and in Warsaw, which remain major centres of medical research today. During World War I she developed mobile radiography units to provide X-ray services to field hospitals.

While a French citizen, Marie Skłodowska Curie, who used both surnames,[7][8] never lost her sense of Polish identity. She taught her daughters the Polish language and took them on visits to Poland.[9] She named the first chemical element she discovered polonium, after her native country.[lower-alpha 1]

Marie Curie died in 1934, aged 66, at a sanatorium in Sancellemoz (Haute-Savoie), France, of aplastic anaemia from exposure to radiation in the course of her scientific research and in the course of her radiological work at field hospitals during World War I.[11] In 1995, she became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the Panthéon in Paris.[12]

Life

Early years

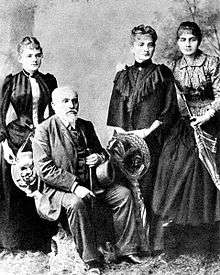

Maria Skłodowska was born in Warsaw, in Congress Poland in the Russian Empire, on 7 November 1867, the fifth and youngest child of well-known teachers Bronisława, née Boguska, and Władysław Skłodowski.[13] The elder siblings of Maria (nicknamed Mania) were Zofia (born 1862, nicknamed Zosia), Józef (born 1863, nicknamed Józio), Bronisława (born 1865, nicknamed Bronia) and Helena (born 1866, nicknamed Hela).[14][15]

On both the paternal and maternal sides, the family had lost their property and fortunes through patriotic involvements in Polish national uprisings aimed at restoring Poland's independence (the most recent had been the January Uprising of 1863–65).[16] This condemned the subsequent generation, including Maria and her elder siblings, to a difficult struggle to get ahead in life.[16] Maria's paternal grandfather, Józef Skłodowski, had been principal of the Lublin primary school attended by Bolesław Prus,[17] who became a leading figure in Polish literature.[18]

Władysław Skłodowski taught mathematics and physics, subjects that Maria was to pursue, and was also director of two Warsaw gymnasia (secondary schools) for boys. After Russian authorities eliminated laboratory instruction from the Polish schools, he brought much of the laboratory equipment home and instructed his children in its use.[14] He was eventually fired by his Russian supervisors for pro-Polish sentiments and forced to take lower-paying posts; the family also lost money on a bad investment and eventually chose to supplement their income by lodging boys in the house.[14] Maria's mother Bronisława operated a prestigious Warsaw boarding school for girls; she resigned from the position after Maria was born.[14] She died of tuberculosis in May 1878, when Maria was ten years old.[14] Less than three years earlier, Maria's oldest sibling, Zofia, had died of typhus contracted from a boarder.[14] Maria's father was an atheist; her mother a devout Catholic.[19] The deaths of Maria's mother and sister caused her to give up Catholicism and become agnostic.[20]

When she was ten years old, Maria began attending the boarding school of J. Sikorska; next, she attended a gymnasium for girls, from which she graduated on 12 June 1883 with a gold medal.[13] After a collapse, possibly due to depression,[14] she spent the following year in the countryside with relatives of her father, and the next year with her father in Warsaw, where she did some tutoring.[13] Unable to enroll in a regular institution of higher education because she was a woman, she and her sister Bronisława became involved with the clandestine Flying University (sometimes translated as Floating University), a Polish patriotic institution of higher learning that admitted women students.[13][14]

Maria made an agreement with her sister, Bronisława, that she would give her financial assistance during Bronisława's medical studies in Paris, in exchange for similar assistance two years later.[13][21] In connection with this, Maria took a position as governess: first as a home tutor in Warsaw; then for two years as a governess in Szczuki with a landed family, the Żorawskis, who were relatives of her father.[13][21] While working for the latter family, she fell in love with their son, Kazimierz Żorawski, a future eminent mathematician.[21] His parents rejected the idea of his marrying the penniless relative, and Kazimierz was unable to oppose them.[21] Maria's loss of the relationship with Żorawski was tragic for both. He soon earned a doctorate and pursued an academic career as a mathematician, becoming a professor and rector of Kraków University. Still, as an old man and a mathematics professor at the Warsaw Polytechnic, he would sit contemplatively before the statue of Maria Skłodowska that had been erected in 1935 before the Radium Institute, which she had founded in 1932.[16][22]

At the beginning of 1890, Bronisława—who a few months earlier had married Kazimierz Dłuski, a Polish physician and social and political activist—invited Maria to join them in Paris. Maria declined because she could not afford the university tuition; it would take her a year and a half longer to gather the necessary funds.[13] She was helped by her father, who was able to secure a more lucrative position again.[21] All that time she continued to educate herself, reading books, exchanging letters, and being tutored herself.[21] In early 1889 she returned home to her father in Warsaw.[13] She continued working as a governess and remained there till late 1891.[21] She tutored, studied at the Flying University, and began her practical scientific training (1890–91) in a chemical laboratory at the Museum of Industry and Agriculture at Krakowskie Przedmieście 66, near Warsaw's Old Town.[13][14][21] The laboratory was run by her cousin Józef Boguski, who had been an assistant in Saint Petersburg to the Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev.[13][21][23]

New life in Paris

In late 1891, she left Poland for France.[24] In Paris, Maria (or Marie, as she would be known in France) briefly found shelter with her sister and brother-in-law before renting a garret closer to the university, in the Latin Quarter, and proceeding with her studies of physics, chemistry, and mathematics at the University of Paris, where she enrolled in late 1891.[25][26] She subsisted on her meagre resources, keeping herself warm during cold winters by wearing all the clothes she had. She focused so hard on her studies that she sometimes forgot to eat.[26]

Skłodowska studied during the day and tutored evenings, barely earning her keep. In 1893, she was awarded a degree in physics and began work in an industrial laboratory of Professor Gabriel Lippmann. Meanwhile, she continued studying at the University of Paris and with the aid of a fellowship she was able to earn a second degree in 1894.[13][26][lower-alpha 2]

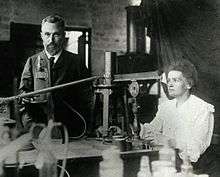

Skłodowska had begun her scientific career in Paris with an investigation of the magnetic properties of various steels, commissioned by the Society for the Encouragement of National Industry (Société d'encouragement pour l'industrie nationale).[26] That same year Pierre Curie entered her life; it was their mutual interest in natural sciences that drew them together.[27] Pierre Curie was an instructor at The City of Paris Industrial Physics and Chemistry Higher Educational Institution (École supérieure de physique et de chimie industrielles de la ville de Paris [ESPCI]).[13] They were introduced by the Polish physicist, Professor Józef Wierusz-Kowalski, who had learned that she was looking for a larger laboratory space, something that Wierusz-Kowalski thought Pierre Curie had access to.[13][26] Though Curie did not have a large laboratory, he was able to find some space for Skłodowska where she was able to begin work.[26]

Their mutual passion for science brought them increasingly closer, and they began to develop feelings for one another.[13][26] Eventually Pierre Curie proposed marriage, but at first Skłodowska did not accept as she was still planning to go back to her native country. Curie, however, declared that he was ready to move with her to Poland, even if it meant being reduced to teaching French.[13] Meanwhile, for the 1894 summer break, Skłodowska returned to Warsaw, where she visited her family.[26] She was still labouring under the illusion that she would be able to work in her chosen field in Poland, but she was denied a place at Kraków University because she was a woman.[16] A letter from Pierre Curie convinced her to return to Paris to pursue a Ph.D.[26] At Skłodowska's insistence, Curie had written up his research on magnetism and received his own doctorate in March 1895; he was also promoted to professor at the School.[26] A contemporary quip would call Skłodowska "Pierre's biggest discovery."[16] On 26 July 1895 they were married in Sceaux (Seine);[28] neither wanted a religious service.[13][26] Curie's dark blue outfit, worn instead of a bridal gown, would serve her for many years as a laboratory outfit.[26] They shared two pastimes: long bicycle trips and journeys abroad, which brought them even closer. In Pierre, Marie had found a new love, a partner, and a scientific collaborator on whom she could depend.[16]

New elements

In 1895, Wilhelm Roentgen discovered the existence of X-rays, though the mechanism behind their production was not yet understood.[29] In 1896, Henri Becquerel discovered that uranium salts emitted rays that resembled X-rays in their penetrating power.[29] He demonstrated that this radiation, unlike phosphorescence, did not depend on an external source of energy but seemed to arise spontaneously from uranium itself. Influenced by these two important discoveries, Curie decided to look into uranium rays as a possible field of research for a thesis.[13][29]

She used an innovative technique to investigate samples. Fifteen years earlier, her husband and his brother had developed a version of the electrometer, a sensitive device for measuring electric charge.[29] Using her husband's electrometer, she discovered that uranium rays caused the air around a sample to conduct electricity. Using this technique, her first result was the finding that the activity of the uranium compounds depended only on the quantity of uranium present.[29] She hypothesized that the radiation was not the outcome of some interaction of molecules but must come from the atom itself.[29] This hypothesis was an important step in disproving the assumption that atoms were indivisible.[29][30]

In 1897, her daughter Irène was born. To support her family, Curie began teaching at the École Normale Supérieure.[24] The Curies did not have a dedicated laboratory; most of their research was carried out in a converted shed next to ESPCI.[24] The shed, formerly a medical school dissecting room, was poorly ventilated and not even waterproof.[31] They were unaware of the deleterious effects of radiation exposure attendant on their continued unprotected work with radioactive substances. ESPCI did not sponsor her research, but she would receive subsidies from metallurgical and mining companies and from various organizations and governments.[24][31][32]

Curie's systematic studies included two uranium minerals, pitchblende and torbernite (also known as chalcolite).[31] Her electrometer showed that pitchblende was four times as active as uranium itself, and chalcolite twice as active. She concluded that, if her earlier results relating the quantity of uranium to its activity were correct, then these two minerals must contain small quantities of another substance that was far more active than uranium.[31][33] She began a systematic search for additional substances that emit radiation, and by 1898 she discovered that the element thorium was also radioactive.[29] Pierre Curie was increasingly intrigued by her work. By mid-1898 he was so invested in it that he decided to drop his work on crystals and to join her.[24][31]

The [research] idea [writes Reid] was her own; no one helped her formulate it, and although she took it to her husband for his opinion she clearly established her ownership of it. She later recorded the fact twice in her biography of her husband to ensure there was no chance whatever of any ambiguity. It [is] likely that already at this early stage of her career [she] realized that... many scientists would find it difficult to believe that a woman could be capable of the original work in which she was involved.[34]

She was acutely aware of the importance of promptly publishing her discoveries and thus establishing her priority. Had not Becquerel, two years earlier, presented his discovery to the Académie des Sciences the day after he made it, credit for the discovery of radioactivity (and even a Nobel Prize), would instead have gone to Silvanus Thompson. Curie chose the same rapid means of publication. Her paper, giving a brief and simple account of her work, was presented for her to the Académie on 12 April 1898 by her former professor, Gabriel Lippmann.[35] Even so, just as Thompson had been beaten by Becquerel, so Curie was beaten in the race to tell of her discovery that thorium gives off rays in the same way as uranium; two months earlier, Gerhard Carl Schmidt had published his own finding in Berlin.[36]

At that time, no one else in the world of physics had noticed what Curie recorded in a sentence of her paper, describing how much greater were the activities of pitchblende and chalcolite than uranium itself: "The fact is very remarkable, and leads to the belief that these minerals may contain an element which is much more active than uranium." She later would recall how she felt "a passionate desire to verify this hypothesis as rapidly as possible."[36] On 14 April 1898, the Curies optimistically weighed out a 100-gram sample of pitchblende and ground it with a pestle and mortar. They did not realize at the time that what they were searching for was present in such minute quantities that they would eventually have to process tonnes of the ore.[36]

In July 1898, Curie and her husband published a joint paper announcing the existence of an element they named "polonium", in honour of her native Poland, which would for another twenty years remain partitioned among three empires (Russian, Austrian, and Prussian).[13] On 26 December 1898, the Curies announced the existence of a second element, which they named "radium", from the Latin word for "ray".[24][31][37] In the course of their research, they also coined the word "radioactivity".[13]

To prove their discoveries beyond any doubt, the Curies sought to isolate polonium and radium in pure form.[31] Pitchblende is a complex mineral; the chemical separation of its constituents was an arduous task. The discovery of polonium had been relatively easy; chemically it resembles the element bismuth, and polonium was the only bismuth-like substance in the ore.[31] Radium, however, was more elusive; it is closely related chemically to barium, and pitchblende contains both elements. By 1898 the Curies had obtained traces of radium, but appreciable quantities, uncontaminated with barium, were still beyond reach.[38] The Curies undertook the arduous task of separating out radium salt by differential crystallization. From a tonne of pitchblende, one-tenth of a gram of radium chloride was separated in 1902. In 1910, she isolated pure radium metal.[31][39] She never succeeded in isolating polonium, which has a half-life of only 138 days.[31]

Between 1898 and 1902, the Curies published, jointly or separately, a total of 32 scientific papers, including one that announced that, when exposed to radium, diseased, tumour-forming cells were destroyed faster than healthy cells.[40]

_and_Marie_Sklodowska_Curie_(1867-1934)%2C_c._1903_(4405627519).jpg)

In 1900, Curie became the first woman faculty member at the École Normale Supérieure and her husband joined the faculty of the University of Paris.[41][42] In 1902 she visited Poland on the occasion of her father's death.[24]

In June 1903, supervised by Gabriel Lippmann, Curie was awarded her doctorate from the University of Paris.[24][43] That month the couple were invited to the Royal Institution in London to give a speech on radioactivity; being a woman, she was prevented from speaking, and Pierre Curie alone was allowed to.[44] Meanwhile, a new industry began developing, based on radium.[41] The Curies did not patent their discovery and benefited little from this increasingly profitable business.[31][41]

Nobel Prizes

In December 1903, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Pierre Curie, Marie Curie, and Henri Becquerel the Nobel Prize in Physics, "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by Professor Henri Becquerel."[24] At first the committee had intended to honour only Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel, but a committee member and advocate for women scientists, Swedish mathematician Magnus Goesta Mittag-Leffler, alerted Pierre to the situation, and after his complaint, Marie's name was added to the nomination.[45] Marie Curie was the first woman to be awarded a Nobel Prize.[24]

Curie and her husband declined to go to Stockholm to receive the prize in person; they were too busy with their work, and Pierre Curie, who disliked public ceremonies, was feeling increasingly ill.[44][45] As Nobel laureates were required to deliver a lecture, the Curies finally undertook the trip in 1905.[45] The award money allowed the Curies to hire their first laboratory assistant.[45] Following the award of the Nobel Prize, and galvanized by an offer from the University of Geneva, which offered Pierre Curie a position, the University of Paris gave him a professorship and the chair of physics, although the Curies still did not have a proper laboratory.[24][41][42] Upon Pierre Curie's complaint, the University of Paris relented and agreed to furnish a new laboratory, but it would not be ready until 1906.[45]

In December 1904, Curie gave birth to their second daughter, Ève.[45] She hired Polish governesses to teach her daughters her native language, and sent or took them on visits to Poland.[9]

On 19 April 1906, Pierre Curie was killed in a road accident. Walking across the Rue Dauphine in heavy rain, he was struck by a horse-drawn vehicle and fell under its wheels, causing his skull to fracture.[24][46] Curie was devastated by her husband's death.[47] On 13 May 1906 the physics department of the University of Paris decided to retain the chair that had been created for her late husband and offer it to Marie. She accepted it, hoping to create a world-class laboratory as a tribute to her husband Pierre.[47][48] She was the first woman to become a professor at the University of Paris.[24]

Curie's quest to create a new laboratory did not end with the University of Paris, however. In her later years, she headed the Radium Institute (Institut du radium, now Curie Institute, Institut Curie), a radioactivity laboratory created for her by the Pasteur Institute and the University of Paris.[48] The initiative for creating the Radium Institute had come in 1909 from Pierre Paul Émile Roux, director of the Pasteur Institute, who had been disappointed that the University of Paris was not giving Curie a proper laboratory and had suggested that she move to the Pasteur Institute.[24][49] Only then, with the threat of Curie leaving, did the University of Paris relent, and eventually the Curie Pavilion became a joint initiative of the University of Paris and the Pasteur Institute.[49]

In 1910 Curie succeeded in isolating radium; she also defined an international standard for radioactive emissions that was eventually named for her and Pierre: the curie.[48] Nevertheless, in 1911 the French Academy of Sciences failed, by one[24] or two votes,[50] to elect her to membership in the Academy. Elected instead was Édouard Branly, an inventor who had helped Guglielmo Marconi develop the wireless telegraph.[51] It was only over half a century later, in 1962, that a doctoral student of Curie's, Marguerite Perey, became the first woman elected to membership in the Academy.

Despite Curie's fame as a scientist working for France, the public's attitude tended toward xenophobia—the same that had led to the Dreyfus affair—which also fuelled false speculation that Curie was Jewish.[24][50] During the French Academy of Sciences elections, she was vilified by the right-wing press as a foreigner and atheist.[50] Her daughter later remarked on the French press' hypocrisy in portraying Curie as an unworthy foreigner when she was nominated for a French honour, but portraying her as a French heroine when she received foreign honours such as her Nobel Prizes.[24]

In 1911, it was revealed that Curie was involved in a year-long affair with physicist Paul Langevin, a former student of Pierre Curie's,[52] a married man who was estranged from his wife.[50] This resulted in a press scandal that was exploited by her academic opponents. Curie (then in her mid-40s) was five years older than Langevin and was misrepresented in the tabloids as a foreign Jewish home-wrecker.[53] When the scandal broke, she was away at a conference in Belgium; on her return, she found an angry mob in front of her house and had to seek refuge, with her daughters, in the home of her friend, Camille Marbo.[50]

International recognition for her work had been growing to new heights, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, overcoming opposition prompted by the Langevin scandal, honoured her a second time, with the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.[16] This award was "in recognition of her services to the advancement of chemistry by the discovery of the elements radium and polonium, by the isolation of radium and the study of the nature and compounds of this remarkable element."[54] She was the first person to win or share two Nobel Prizes, and remains alone with Linus Pauling as Nobel laureates in two fields each. A delegation of celebrated Polish men of learning, headed by novelist Henryk Sienkiewicz, encouraged her to return to Poland and continue her research in her native country.[16] Curie's second Nobel Prize enabled her to persuade the French government into supporting the Radium Institute, built in 1914, where research was conducted in chemistry, physics, and medicine.[49] A month after accepting her 1911 Nobel Prize, she was hospitalised with depression and a kidney ailment. For most of 1912, she avoided public life but did spend time in England with her friend and fellow physicist, Hertha Ayrton. She returned to her laboratory only in December, after a break of about 14 months.[54]

In 1912, the Warsaw Scientific Society offered her the directorship of a new laboratory in Warsaw but she declined, focusing on the developing Radium Institute to be completed in August 1914, and on a new street named Rue Pierre-Curie.[49][54] She was appointed Director of the Curie Laboratory in the Radium Institute of the University of Paris, founded in 1914.[55] She visited Poland in 1913 and was welcomed in Warsaw but the visit was mostly ignored by the Russian authorities. The Institute's development was interrupted by the coming war, as most researchers were drafted into the French Army, and it fully resumed its activities in 1919.[49][54][56]

World War I

During World War I, Curie recognised that wounded soldiers were best served if operated upon as soon as possible.[57] She saw a need for field radiological centres near the front lines to assist battlefield surgeons.[56] After a quick study of radiology, anatomy, and automotive mechanics she procured X-ray equipment, vehicles, auxiliary generators, and developed mobile radiography units, which came to be popularly known as petites Curies ("Little Curies").[56] She became the director of the Red Cross Radiology Service and set up France's first military radiology centre, operational by late 1914.[56] Assisted at first by a military doctor and her 17-year-old daughter Irène, Curie directed the installation of 20 mobile radiological vehicles and another 200 radiological units at field hospitals in the first year of the war.[49][56] Later, she began training other women as aides.[58]

In 1915, Curie produced hollow needles containing "radium emanation", a colourless, radioactive gas given off by radium, later identified as radon, to be used for sterilizing infected tissue. She provided the radium from her own one-gram supply.[58] It is estimated that over a million wounded soldiers were treated with her X-ray units.[20][49] Busy with this work, she carried out very little scientific research during that period.[49] In spite of all her humanitarian contributions to the French war effort, Curie never received any formal recognition of it from the French government.[56]

Also, promptly after the war started, she attempted to donate her gold Nobel Prize medals to the war effort but the French National Bank refused to accept them.[58] She did buy war bonds, using her Nobel Prize money.[58] She said:

I am going to give up the little gold I possess. I shall add to this the scientific medals, which are quite useless to me. There is something else: by sheer laziness I had allowed the money for my second Nobel Prize to remain in Stockholm in Swedish crowns. This is the chief part of what we possess. I should like to bring it back here and invest it in war loans. The state needs it. Only, I have no illusions: this money will probably be lost.[57]

She was also an active member in committees of Polonia in France dedicated to the Polish cause.[59] After the war, she summarized her wartime experiences in a book, Radiology in War (1919).[58]

Postwar years

In 1920, for the 25th anniversary of the discovery of radium, the French government established a stipend for her; its previous recipient was Louis Pasteur (1822–95).[49] In 1921, she was welcomed triumphantly when she toured the United States to raise funds for research on radium. Mrs. William Brown Meloney, after interviewing Curie, created a Marie Curie Radium Fund and raised money to buy radium, publicising her trip.[49][60][lower-alpha 3]

In 1921, U.S. President Warren G. Harding received her at the White House to present her with the 1 gram of radium collected in the United States, and the First Lady praised her as an example of a professional achiever who was also a supportive wife.[4][62] Before the meeting, recognising her growing fame abroad, and embarrassed by the fact that she had no French official distinctions to wear in public, the French government offered her a Legion of Honour award, but she refused.[62][63] In 1922 she became a fellow of the French Academy of Medicine.[49] She also travelled to other countries, appearing publicly and giving lectures in Belgium, Brazil, Spain, and Czechoslovakia.[64]

Led by Curie, the Institute produced four more Nobel Prize winners, including her daughter Irène Joliot-Curie and her son-in-law, Frédéric Joliot-Curie.[65] Eventually it became one of the world's four major radioactivity-research laboratories, the others being the Cavendish Laboratory, with Ernest Rutherford; the Institute for Radium Research, Vienna, with Stefan Meyer; and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Chemistry, with Otto Hahn and Lise Meitner.[65][66]

In August 1922 Marie Curie became a member of the League of Nations' newly created International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation.[67][12] She sat on the Committee until 1934 and contributed to League of Nations' scientific coordination with other prominent researchers such as Albert Einstein, Hendrik Lorentz, and Henri Bergson.[68] In 1923 she wrote a biography of her late husband, titled Pierre Curie.[69] In 1925 she visited Poland to participate in a ceremony laying the foundations for Warsaw's Radium Institute.[49] Her second American tour, in 1929, succeeded in equipping the Warsaw Radium Institute with radium; the Institute opened in 1932, with her sister Bronisława its director.[49][62] These distractions from her scientific labours, and the attendant publicity, caused her much discomfort but provided resources for her work.[62] In 1930 she was elected to the International Atomic Weights Committee, on which she served until her death.[70] In 1931, Curie was awarded the Cameron Prize for Therapeutics of the University of Edinburgh.[71]

Death

Curie visited Poland for the last time in early 1934.[16][72] A few months later, on 4 July 1934, she died at the Sancellemoz sanatorium in Passy, Haute-Savoie, from aplastic anaemia believed to have been contracted from her long-term exposure to radiation.[49][73]

The damaging effects of ionising radiation were not known at the time of her work, which had been carried out without the safety measures later developed.[72] She had carried test tubes containing radioactive isotopes in her pocket,[74] and she stored them in her desk drawer, remarking on the faint light that the substances gave off in the dark.[75] Curie was also exposed to X-rays from unshielded equipment while serving as a radiologist in field hospitals during the war.[58] Although her many decades of exposure to radiation caused chronic illnesses (including near-blindness due to cataracts) and ultimately her death, she never really acknowledged the health risks of radiation exposure.[76]

She was interred at the cemetery in Sceaux, alongside her husband Pierre.[49] Sixty years later, in 1995, in honour of their achievements, the remains of both were transferred to the Paris Panthéon. Their remains were sealed in a lead lining because of the radioactivity.[77] She became the first woman to be honoured with interment in the Panthéon on her own merits.[12]

Because of their levels of radioactive contamination, her papers from the 1890s are considered too dangerous to handle.[78] Even her cookbook is highly radioactive.[79] Her papers are kept in lead-lined boxes, and those who wish to consult them must wear protective clothing.[79] In her last year, she worked on a book, Radioactivity, which was published posthumously in 1935.[72]

Legacy

The physical and societal aspects of the Curies' work contributed to shaping the world of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.[80] Cornell University professor L. Pearce Williams observes:

The result of the Curies' work was epoch-making. Radium's radioactivity was so great that it could not be ignored. It seemed to contradict the principle of the conservation of energy and therefore forced a reconsideration of the foundations of physics. On the experimental level the discovery of radium provided men like Ernest Rutherford with sources of radioactivity with which they could probe the structure of the atom. As a result of Rutherford's experiments with alpha radiation, the nuclear atom was first postulated. In medicine, the radioactivity of radium appeared to offer a means by which cancer could be successfully attacked.[39]

If Curie's work helped overturn established ideas in physics and chemistry, it has had an equally profound effect in the societal sphere. To attain her scientific achievements, she had to overcome barriers, in both her native and her adoptive country, that were placed in her way because she was a woman. This aspect of her life and career is highlighted in Françoise Giroud's Marie Curie: A Life, which emphasizes Curie's role as a feminist precursor.[16]

She was known for her honesty and moderate lifestyle.[24][80] Having received a small scholarship in 1893, she returned it in 1897 as soon as she began earning her keep.[13][32] She gave much of her first Nobel Prize money to friends, family, students, and research associates.[16] In an unusual decision, Curie intentionally refrained from patenting the radium-isolation process so that the scientific community could do research unhindered.[81] She insisted that monetary gifts and awards be given to the scientific institutions she was affiliated with rather than to her.[80] She and her husband often refused awards and medals.[24] Albert Einstein reportedly remarked that she was probably the only person who could not be corrupted by fame.[16]

Honours, tributes

As one of the most famous scientists, Marie Curie has become an icon in the scientific world and has received tributes from across the globe, even in the realm of pop culture.[82] In a 2009 poll carried out by New Scientist, she was voted the "most inspirational woman in science". Curie received 25.1 percent of all votes cast, nearly twice as many as second-place Rosalind Franklin (14.2 per cent).[83][84]

Poland and France declared 2011 the Year of Marie Curie, and the United Nations declared that this would be the International Year of Chemistry.[85] An artistic installation celebrating "Madame Curie" filled the Jacobs Gallery at San Diego's Museum of Contemporary Art.[86] On 7 November, Google celebrated the anniversary of her birth with a special Google Doodle.[87] On 10 December, the New York Academy of Sciences celebrated the centenary of Marie Curie's second Nobel Prize in the presence of Princess Madeleine of Sweden.[88]

Marie Curie was the first woman to win a Nobel Prize, the first person to win two Nobel Prizes, the only woman to win in two fields, and the only person to win in multiple sciences.[89] Awards that she received include:

- Nobel Prize in Physics (1903, with her husband Pierre Curie and Henri Becquerel)[24]

- Davy Medal (1903, with Pierre)[64][90]

- Matteucci Medal (1904, with Pierre)[90]

- Actonian Prize (1907)[91]

- Elliott Cresson Medal (1909)[92]

- Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1911)[16]

- Franklin Medal of the American Philosophical Society (1921)[93]

Marie Curie's 1898 publication with her husband and their collaborator Gustave Bémont[94] of their discovery of radium and polonium was honoured by a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society presented to the ESPCI Paris in 2015.[95][96]

In 1995, she became the first woman to be entombed on her own merits in the Panthéon, Paris.[12] The curie (symbol Ci), a unit of radioactivity, is named in honour of her and Pierre Curie (although the commission which agreed on the name never clearly stated whether the standard was named after Pierre, Marie or both of them).[97] The element with atomic number 96 was named curium.[98] Three radioactive minerals are also named after the Curies: curite, sklodowskite, and cuprosklodowskite.[99] She received numerous honorary degrees from universities across the world.[62] The Marie Skłodowska-Curie Actions fellowship program of the European Union for young scientists wishing to work in a foreign country is named after her.[100] In Poland, she had received honorary doctorates from the Lwów Polytechnic (1912),[101] Poznań University (1922), Kraków's Jagiellonian University (1924), and the Warsaw Polytechnic (1926).[85]

In 1920 she became the first female member of The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters.[102] In 1921, in the U.S., she was awarded membership in the Iota Sigma Pi women scientists' society.[103] In 1924, she became an Honorary Member of the Polish Chemical Society.[104]

Her name is included on the Monument to the X-ray and Radium Martyrs of All Nations, erected in Hamburg, Germany in 1936.[105]

Numerous locations around the world are named after her. In 2007, a metro station in Paris was renamed to honour both of the Curies.[99] Polish nuclear research reactor Maria is named after her.[106] The 7000 Curie asteroid is also named after her.[99] A KLM McDonnell Douglas MD-11 (registration PH-KCC) is named in her honour.[107]

Several institutions bear her name, starting with the two Curie institutes: the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Institute of Oncology, in Warsaw and the Institut Curie in Paris. She is the patron of Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, in Lublin, founded in 1944; and of Pierre and Marie Curie University (Paris VI), France's pre-eminent science university. In Britain, Marie Curie Cancer Care was organized in 1948 to care for the terminally ill.[108]

Two museums are devoted to Marie Curie. In 1967, the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum was established in Warsaw's "New Town", at her birthplace on ulica Freta (Freta Street).[16] Her Paris laboratory is preserved as the Musée Curie, open since 1992.[109]

Several works of art bear her likeness. In 1935, Michalina Mościcka, wife of Polish President Ignacy Mościcki, unveiled a statue of Marie Curie before Warsaw's Radium Institute. During the 1944 Second World War Warsaw Uprising against the Nazi German occupation, the monument was damaged by gunfire; after the war it was decided to leave the bullet marks on the statue and its pedestal.[16] In 1955 Jozef Mazur created a stained glass panel of her, the Maria Skłodowska-Curie Medallion, featured in the University at Buffalo Polish Room.[110]

A number of biographies are devoted to her. In 1938 her daughter, Ève Curie, published Madame Curie. In 1987 Françoise Giroud wrote Marie Curie: A Life. In 2005 Barbara Goldsmith wrote Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie.[85] In 2011 Lauren Redniss published Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout.[111]

Marie Curie has been the subject of several biographical films:

- Greer Garson and Walter Pidgeon starred in the 1943 U.S. Oscar-nominated film, Madame Curie, based on her life.[69]

- In 1997, a French film about Pierre and Marie Curie was released, Les Palmes de M. Schutz. It was adapted from a play of the same name. In the film, Marie Curie was played by Isabelle Huppert.[112]

- Marie Curie: The Courage of Knowledge was produced internationally in Europe and released in 2016.

- Radioactive was released in 2019.

Curie is the subject of the 2013 play False Assumptions by Lawrence Aronovitch, in which the ghosts of three other women scientists observe events in her life.[113] Curie has also been portrayed by Susan Marie Frontczak in her play Manya: The Living History of Marie Curie, a one-woman show performed in 30 U.S. states and nine countries, by 2014.[114]

Curie's likeness also has appeared on banknotes, stamps and coins around the world.[99] She was featured on the Polish late-1980s 20,000-złoty banknote[115] as well as on the last French 500-franc note, before the franc was replaced by the euro.[116] Curie-themed postage stamps from Mali, the Republic of Togo, Zambia, and the Republic of Guinea actually show a picture of Susan Marie Frontczak portraying Curie in a 2001 picture by Paul Schroeder.[114]

In 2011, on the centenary of Marie Curie's second Nobel Prize, an allegorical mural was painted on the façade of her Warsaw birthplace. It depicted an infant Maria Skłodowska holding a test tube from which emanated the elements that she would discover as an adult: polonium and radium.

Also in 2011, a new Warsaw bridge over the Vistula River was named in her honour.[117]

In January 2020, Satellogic, a high-resolution Earth observation imaging and analytics company, launched a ÑuSat type micro-satellite named in honour of Marie Curie.[118]

See also

- Charlotte Hoffman Kellogg, friend

- Eusapia Palladino: Spiritualist medium whose Paris séances were attended by Pierre and Marie Curie.

- Marie Curie Medal

- Genius, a television series depicting Einstein's life

- List of female Nobel laureates

- List of multiple discoveries

- List of Poles (Chemistry)

- List of Poles (Physics)

- Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum, Warsaw, Poland

- Marie Curie Gargoyle (1988), University of Oregon

- Poles

- Timeline of women in science

- Treatise on Radioactivity

- Women in chemistry

Notes

- Poland had been partitioned in the 18th century among Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and it was Maria Skłodowska Curie's hope that naming the element after her native country would bring world attention to Poland's lack of independence as a sovereign state. Polonium may have been the first chemical element named to highlight a political question.[10]

- Sources vary concerning the field of her second degree. Tadeusz Estreicher, in the 1938 Polski słownik biograficzny entry, writes that, while many sources state she earned a degree in mathematics, this is incorrect, and that her second degree was in chemistry.[13]

- Marie Skłodowska Curie was escorted to the United States by the American author and social activist Charlotte Hoffman Kellogg.[61]

References

- "Marie Curie Facts". Nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- "ESPCI Paris : Prestige". www.espci.fr. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- Jones, Daniel (2011). Roach, Peter; Setter, Jane; Esling, John (eds.). Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary (18th ed.). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-15253-2.

- Julie Des Jardins (October 2011). "Madame Curie's Passion". Smithsonian Magazine. Archived from the original on 27 November 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "The Discovery of Radioactivity". Berkeley Lab. Archived from the original on 1 November 2015.

The term radioactivity was actually coined by Marie Curie […].

- "Marie Curie and the radioactivity, The 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics". nobelprize.org. Archived from the original on 30 July 2018.

Marie called this radiation radioactivity—"radio" means radiation.

- See her signature, "M. Skłodowska Curie", in the infobox.

- Her 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was granted to "Marie Sklodowska Curie" File:Marie Skłodowska-Curie's Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1911.jpg.

- Goldsmith, Barbara (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 149. ISBN 978-0-393-05137-7. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Kabzińska, Krystyna (1998). "Chemiczne i polskie aspekty odkrycia polonu i radu" [Chemical and Polish Aspects of Polonium and Radium Discovery]. Przemysł Chemiczny (The Chemical Industry) (in Polish). 77: 104–107.

- "The Genius of Marie Curie: The Woman Who Lit Up the World" on YouTube (a 2013 BBC documentary)

- "Marie Curie Enshrined in Pantheon". New York Times. 21 April 1995. Archived from the original on 22 January 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). "Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich". Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 (in Polish). p. 111.

- "Marie Curie – Polish Girlhood (1867–1891) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Nelson, Craig (2014). The Age of Radiance: The Epic Rise and Dramatic Fall of the Atomic Era. Simon & Schuster. p. 18. ISBN 978-1-4516-6045-6. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2016.

- Wojciech A. Wierzewski (21 June 2008). "Mazowieckie korzenie Marii" [Maria's Mazowsze Roots]. Gwiazda Polarna. 100 (13): 16–17. Archived from the original on 21 March 2009. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- Monika Piątkowska, Prus: Śledztwo biograficzne (Prus: A Biographical Investigation), Kraków, Wydawnictwo Znak, 2017, ISBN 978-83-240-4543-3, pp. 49–50.

- Miłosz, Czesław (1983). The History of Polish Literature. University of California Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7.

Undoubtedly the most important novelist of the period was Bolesław Prus...

- Barker, Dan (2011). The Good Atheist: Living a Purpose-Filled Life Without God. Ulysses Press. p. 171. ISBN 978-1-56975-846-5. Archived from the original on 2 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

Unusually at such an early age, she became what T.H. Huxley had just invented a word for: agnostic.

- "Marie Curie – Polish Girlhood (1867–1891) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). "Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich". Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 (in Polish). p. 112.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 32. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Marie Curie – Student in Paris (1891–1897) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- L. Pearce Williams (1986). "Curie, Pierre and Marie". Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 8. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier, Inc. p. 331.

- les Actus DN. "Marie Curie". Archived from the original on 2 November 2013. Retrieved 24 May 2013.

- "Marie Curie – Research Breakthroughs (1807–1904)Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. pp. 61–63. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Marie Curie – Research Breakthroughs (1807–1904)Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Marie Curie – Student in Paris (1891–1897) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. pp. 64–65. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "The Discovery of Radioactivity". Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. 9 August 2000. Archived from the original on 14 August 2012. Retrieved 2 August 2012.

- L. Pearce Williams (1986). "Curie, Pierre and Marie". Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 8. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier, Inc. pp. 331–332.

- L. Pearce Williams (1986). "Curie, Pierre and Marie". Encyclopedia Americana, vol. 8. Danbury, Connecticut: Grolier, Inc. p. 332.

- "Marie Sklodowska Curie", Encyclopedia of World Biography, 2nd ed., vol. 4, Detroit, Gale, 2004, pp. 339–41. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 3 June 2013.

- "Marie Curie – Research Breakthroughs (1807–1904) Part 3". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 18 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Quinn, Susan (1996). Marie Curie: A Life. Da Capo Press. pp. 176, 203. ISBN 978-0-201-88794-5. Archived from the original on 31 October 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Mould, R. F. (1998). "The discovery of radium in 1898 by Maria Sklodowska-Curie (1867–1934) and Pierre Curie (1859–1906) with commentary on their life and times". The British Journal of Radiology. 71 (852): 1229–54. doi:10.1259/bjr.71.852.10318996. PMID 10318996.

- "Marie Curie – Recognition and Disappointment (1903–1905) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Marie Curie – Recognition and Disappointment (1903–1905) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Prof. Curie killed in a Paris street" (PDF). The New York Times. 20 April 1906. Archived from the original on 25 July 2018. Retrieved 8 February 2011.

- "Marie Curie – Tragedy and Adjustment (1906–1910) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 26 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Marie Curie – Tragedy and Adjustment (1906–1910) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). "Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich". Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 (in Polish). p. 113.

- "Marie Curie – Scandal and Recovery (1910–1913) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Goldsmith, Barbara (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 170–71. ISBN 978-0-393-05137-7. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. pp. 44, 90. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Goldsmith, Barbara (2005). Obsessive Genius: The Inner World of Marie Curie. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 165–76. ISBN 978-0-393-05137-7. Archived from the original on 5 May 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- "Marie Curie – Scandal and Recovery (1910–1913) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Marie Curie-biographical". Nobel Prize.org. 2014. Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- "Marie Curie – War Duty (1914–1919) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 2 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Coppes-Zantinga, A. R. and Coppes, M. J. (1998), Marie Curie's contributions to radiology during World War I. Med. Pediatr. Oncol., 31: 541–543. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-911X(199812)31:6<541::AID-MPO19>3.0.CO;2-0

- "Marie Curie – War Duty (1914–1919) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 12 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Śladkowski, Wiesław (1980). Emigracja polska we Francji 1871–1918 (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Lubelskie. p. 274. ISBN 978-83-222-0147-3. Archived from the original on 17 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Ann M. Lewicki (2002). "Marie Sklodowska Curie in America, 1921". Radiology. 223 (2): 299–303. doi:10.1148/radiol.2232011319. PMID 11997527.

- Charlotte Kellogg (Carmel, California), An intimate picture of Madame Curie, from diary notes covering a friendship of fifteen years. In the Joseph Halle Schaffner Collection in the History of Science, 1642–1961, Special Collections, University of Chicago Library.

- "Marie Curie – The Radium Institute (1919–1934) Part 1". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Pasachoff, Naomi (1996). Marie Curie:And the Science of Radioactivity: And the Science of Radioactivity. Oxford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-19-509214-1. Archived from the original on 28 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Zwoliński, Zbigniew. "Science in Poland – Maria Sklodowska-Curie". Uniwersytet im. Adama Mickiewicza w Poznaniu. Archived from the original on 11 September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Marie Curie – The Radium Institute (1919–1934) Part 2". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 October 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- "Chemistry International – Newsmagazine for IUPAC". International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry. 5 January 2011. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Grandjean, Martin (2017). "Analisi e visualizzazioni delle reti in storia. L'esempio della cooperazione intellettuale della Società delle Nazioni". Memoria e Ricerca (2): 371–393. doi:10.14647/87204. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 2 January 2018. See also: French version Archived 7 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine (PDF) and English summary Archived 2 November 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- Grandjean, Martin (2018). Les réseaux de la coopération intellectuelle. La Société des Nations comme actrice des échanges scientifiques et culturels dans l'entre-deux-guerres [The Networks of Intellectual Cooperation. The League of Nations as an Actor of the Scientific and Cultural Exchanges in the Inter-War Period] (in French). Lausanne: Université de Lausanne. Archived from the original on 12 September 2018. Retrieved 27 October 2018. (i.e. pp. 303-305)

- "Marie Curie and Her Legend". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 1 January 2012. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Norman E. Holden (2004). "Atomic Weights and the International Committee: A Historical Review". Chemistry International. Archived from the original on 19 December 2018. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- "Maria Skłodowska-Curie". Europeana Exhibitions. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Marie Curie – The Radium Institute (1919–1934) Part 3". American Institute of Physics. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Rollyson, Carl (2004). Marie Curie: Honesty In Science. iUniverse. p. x. ISBN 978-0-595-34059-0. Archived from the original on 24 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- James Shipman; Jerry D. Wilson; Aaron Todd (2012). An Introduction to Physical Science. Cengage Learning. p. 263. ISBN 978-1-133-10409-4. Archived from the original on 27 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Blom, Philipp (2008). "1903: A Strange Luminescence". The Vertigo Years: Europe, 1900–1914. Basic Books. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-465-01116-2.

The glowing tubes looked like faint, fairy lights.

- Denise Grady (6 October 1998), A Glow in the Dark, and a Lesson in Scientific Peril Archived 10 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times; accessed 21 December 2016.

- Tasch, Barbara. "Marie Curie's Belongings Will Be Radioactive For Another 1,500 Years". Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- Estes, Adam Clark. "Marie Curie's century-old radioactive notebook still requires lead box". Archived from the original on 13 September 2017. Retrieved 9 September 2017.

- Bryson, Bill (2012). A Short History of Nearly Everything. Random House Digital, Inc. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-385-67450-8. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- Estreicher, Tadeusz (1938). "Curie, Maria ze Skłodowskich". Polski słownik biograficzny, vol. 4 (in Polish). p. 114.

- Robert William Reid (1974). Marie Curie. New American Library. p. 265. ISBN 978-0-00-211539-1. Archived from the original on 11 June 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Borzendowski, Janice (2009). Sterling Biographies: Marie Curie: Mother of Modern Physics. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-4027-5318-3. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Most inspirational woman scientist revealed". Newscientist.com. 2 July 2009. Archived from the original on 6 December 2011. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- "Marie Curie voted greatest female scientist". The Daily Telegraph. London. 2 July 2009. Archived from the original on 5 July 2009. Retrieved 10 April 2010.

Marie Curie, the Nobel Prize-winning nuclear physicist has been voted the greatest woman scientist of all time.

- "2011 – The Year of Marie Skłodowska-Curie". Cosmopolitanreview.com. 3 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Chute, James (5 March 2011). "Video artist Steinkamp's flowery 'Madame Curie' is challenging, and stunning". signonsandiego.com. Archived from the original on 7 May 2011. Retrieved 14 April 2011.

- "Marie Curie's 144th Birthday Anniversary". DoodleToday.com. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 November 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2011.

- "Princess Madeleine attends celebrations to mark anniversary of Marie Curie's second Nobel Prize". Sveriges Kungahus. Archived from the original on 5 January 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- "Nobel Prize Facts". Nobelprize.org. 22 April 2011. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Eve Curie; Vincent Sheean (1999). Madame Curie: A Biography. Turtleback Books. p. 389. ISBN 978-0-613-18127-3. Archived from the original on 26 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Scientific Notes and News". Science. 25 (647): 839–840. 1907. Bibcode:1907Sci....25..839.. doi:10.1126/science.25.647.839. ISSN 0036-8075. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- "Franklin Laureate Database". The Franklin Institute Awards. The Franklin Institute. Archived from the original on 12 December 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- "Minutes". Proc. Am. Philos. Soc. 60 (4): iii–xxiv. 1921. JSTOR 984523.

- Curie, M.P.; Curie, Mme .P; Bémont, M.G. (26 December 1898). "sur une nouvelle substance fortement redio-active, contenue dans la pechblende". Comptes Rendus de l'Académie des Sciences (in French). Paris. 127: 1215–1217. Archived from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- "2015 Awardees". American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- "Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award" (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- Paul W. Frame (October–November 1996). "How the Curie Came to Be". Oak Ridge Associated Universities. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 30 April 2008.

- "Curium". Chemistry in its element. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 9 August 2016. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Borzendowski, Janice (2009). Sterling Biographies: Marie Curie: Mother of Modern Physics. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4027-5318-3. Archived from the original on 30 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Marie Curie Actions" (PDF). European Commission. 2012. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 June 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2012.

- "Coventry professor's honorary degree takes him in footsteps of Marie Curie". Birmingham Press. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 2 April 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- "MarieCurie | Royal Academy". www.royalacademy.dk. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Professional Awards". Iota Stigma Pi: National Honor Society for Women in Chemistry. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- "President of honour and honorary members of PTChem". Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- "Museum of Modern Imaging". Archived from the original on 21 February 2019. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- "IEA – reaktor Maria". Institute of Atomic Energy, Poland. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Picture of the McDonnell Douglas MD-11 aircraft". Airliners.net. Archived from the original on 18 March 2009. Retrieved 27 April 2011.

- Charity Commission. Marie Curie (charity), registered charity no. 207994.

- Curie, Institut (17 December 2010). "Curie museum | Institut Curie". Curie.fr. Archived from the original on 6 September 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Marie Curie Medallion Returns to UB Polish Collection By Way of eBay". News Center, University of Buffalo. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Radioactive: Marie and Pierre Curie, a Tale of Love and Fallout". Cosmopolitanreview.com. 3 July 2011. Archived from the original on 14 August 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- "Les-Palmes-de-M-Schutz (1997)". Movies. New York Times. 5 June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 27 August 2012.

- Mixing Science With Theatre Archived 12 May 2014 at the Wayback Machine – Ottawa Sun, March 2013

- Main, Douglas (7 March 2014). "This Famous Image Of Marie Curie Isn't Marie Curie". Popular Science www.popsci.com. Archived from the original on 10 November 2014. Retrieved 15 November 2014.

- Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (India) (1997). Science reporter. Council of Scientific & Industrial Research. p. 117. Archived from the original on 4 May 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Letcher, Piers (2003). Eccentric France. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 59. ISBN 978-1-84162-068-8. Archived from the original on 20 November 2015. Retrieved 7 September 2015.

- "Most Marii Skłodowskiej-Curie, Polska » Vistal Gdynia". www.vistal.pl. Archived from the original on 29 March 2016. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- "China lofts 4 satellites into orbit with its second launch of 2020". space.com. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

Further reading

Nonfiction

- Curie, Marie (1921). . Poughkeepsie: Vassar College.

- Curie, Eve (2001). Madame Curie: A Biography. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-81038-1.

- Dzienkiewicz, Marta. Polish Pioneers: Book of Prominent Poles. Rzezak, Joanna; Karski, Piotr; Monod-Gayraud, Agnes. Warsaw. ISBN 9788365341686. OCLC 1060750234.

- Giroud, Françoise (1986). Marie Curie: A life. Holmes & Meier. ISBN 978-0-8419-0977-9. translated by Lydia Davis.

- Kaczorowska, Teresa (2011). Córka mazowieckich równin, czyli, Maria Skłodowska-Curie z Mazowsza [Daughter of the Mazovian Plains: Maria Skłodowska–Curie of Mazowsze] (in Polish). Związek Literatów Polskich, Oddział w Ciechanowie. ISBN 978-83-89408-36-5. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- Opfell, Olga S. (1978). The Lady Laureates : Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize. Metuchen, N.J.& London: Scarecrow Press. pp. 147–164. ISBN 978-0-8108-1161-4.

- Pasachoff, Naomi (1996). Marie Curie and the Science of Radioactivity. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-509214-1.

- Quinn, Susan (1996). Marie Curie: A Life. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-201-88794-5.

- Redniss, Lauren (2010). Radioactive: Marie & Pierre Curie: A Tale of Love and Fallout. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-135132-7.

- Wirten, Eva Hemmungs (2015). Making Marie Curie: Intellectual Property and Celebrity Culture in an Age of Information. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-23584-4. Retrieved 15 March 2016.

Fiction

- Olov Enquist, Per (2006). The Book about Blanche and Marie. New York: Overlook. ISBN 978-1-58567-668-2. A 2004 novel by Per Olov Enquist featuring Maria Skłodowska-Curie, neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot, and his Salpêtrière patient "Blanche" (Marie Wittman). The English translation was published in 2006.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Marie Curie |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Marie Curie |

- Out of the Shadows – A study of women physicists

- The official web page of Maria Curie Skłodowska University in Lublin, Poland in English.

- Detailed Biography at Science in Poland website; with quotes, photographs, links etc.

- European Marie Curie Fellowships

- Marie Curie Fellowship Association

- Works by Marie Curie at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marie Curie at Internet Archive

- Works by Marie Curie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Marie Sklodowska Curie: Her Life as a Media Compendium

- Marie and Pierre Curie and the Discovery of Polonium and Radium Chronology from nobelprize.org

- Annotated bibliography of Marie Curie from the Alsos Digital Library

- Obituary, New York Times, 5 July 1934 "Mme. Curie Is Dead; Martyr to Science"

- Some places and memories related to Marie Curie

- Marie Curie on the 500 French Franc and 20000 old Polish zloty banknotes.

- Marie Curie on IMDb – Animated biography of Marie Curie on DVD from an animated series of world and American history – Animated Hero Classics distributed by Nest Learning.

- Marie Curie – More than Meets the Eye on IMDb – Live action portrayal of Marie Curie on DVD from the Inventors Series produced by Devine Entertainment.

- Marie Curie on IMDb – Portrayal of Marie Curie in a television mini series produced by the BBC

- "Marie Curie and the Study of Radioactivity" at American Institute of Physics website. (Site also has a short version for kids entitled "Her story in brief!".)

- "Marie Curie Walking Tour of Paris". Hypatia. Retrieved 7 November 2011.

- Works by Marie Curie at Gallica

- Streets and schools worldwide named after her.

- Location of her grave on OpenStreetMap.

- Newspaper clippings about Marie Curie in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW