Argand lamp

The Argand lamp is a type of oil lamp invented in 1780 by Aimé Argand. Its output is 6 to 10 candelas, brighter than that of earlier lamps. Its more complete combustion of the candle wick and oil than in other lamps required much less frequent trimming of the wick.

In France, the lamp is called "Quinquet", after Antoine-Arnoult Quinquet, a pharmacist in Paris, who used the idea originated by Argand and popularized it in France. Quinquet sometimes is credited with the addition of the glass chimney to the lamp.[1]

Design

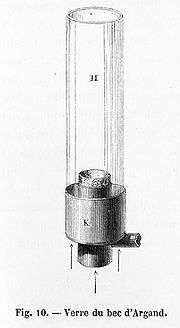

The Argand lamp had a sleeve-shaped wick mounted so that air can pass both through the center of the wick and also around the outside of the wick before being drawn into a cylindrical chimney which steadies the flame and improves the flow of air. Early models used ground glass which was sometimes tinted around the wick.

An Argand lamp used whale oil, seal oil, colza, olive oil[2] or other vegetable oil as fuel which was supplied by a gravity feed from a reservoir mounted above the burner.

A disadvantage of the original Argand arrangement was that the oil reservoir needed to be above the level of the burner because the heavy, sticky vegetable oil would not rise far up the wick. This made the lamps top heavy and cast a shadow in one direction away from the lamp's flame. The Carcel lamp of 1800, which used a clockwork pump to allow the reservoir to sit beneath the burner, and Franchot's spring-driven Moderator lamp of 1836 avoided these problems.

The same principle was also used for cooking and boiling water due to its 'affording much the strongest heat without smoke'.[3]

History

The Argand lamp was introduced to Thomas Jefferson in Paris in 1784 and according to him gave off "a light equal to six or eight candles."[4]

These new lamps, much more complex and costly than the previous primitive oil lamps, were first adopted by the well-to-do, but soon spread to the middle classes and eventually the less well-off as well. Argand lamps were manufactured in a great variety of decorative forms and quickly became popular in America.[5] They were much used as theatrical footlights.[6]

It was the lamp of choice until about 1850 when kerosene lamps were introduced. Kerosene was cheaper than vegetable oil, it produced a whiter flame, and as a liquid of low viscosity it could easily travel up a wick eliminating the need for complicated mechanisms to feed the fuel to the burner.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to argand lamps. |

- Bude-Light: a very bright vegetable oil lamp that works by introducing oxygen into the centre of an Argand burner.

- Lewis lamp

Notes

- "Lamp." Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 6th Edition (2011): 1. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 December 2011.

- "Lamp." Encyclopædia Britannica: or, a dictionary of Arts, Science, and Miscellaneous Literature. 6th ed. 1823 Web. 5 December 2011

- An Encyclopędia of Domestic Economy:Comprising Such Subjects As Are Most Immediately Connected with Housekeeping. 1844. p. 841.

- Crowley, John E. The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities & Design in Early Modern Britain & Early America. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 2000. Web. 5 December 2011

- McCullough, Hollis Koons. Telfair Museum of Art: Collection Highlights. McCullough, Hollis Koons. Telfair Museum of Art: Collection Highlights. Savannah, GA: Telfair Museum of Art, 2005.Web. 5 December 2011

- Banham, Martin (7 March 1996). The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Theatre. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-44654-9.

References

- History of the lamp

- Dimond, E. W. The Chemistry of Combustion (E R Fiske, 1857), p. 139 ff.

- Wolfe, John J., Brandy, Balloons, & Lamps: Ami Argand, 1750–1803 (Southern Illinois University, 1999) ISBN 0-8093-2278-1.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Argand lamps. |

_-_cropped.jpg)