Zihui

The 1615 Zìhuì is a Chinese dictionary edited by the Ming Dynasty scholar Mei Yingzuo (梅膺祚). It is renowned for introducing two lexicographical innovations that continue to be used in the present day: the 214-radical system for indexing Chinese characters, which replaced the classic Shuowen Jiezi dictionary's 540-radical system, and the radical-and-stroke sorting method.

| Zihui | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 字彙 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 字汇 | ||||||||

| Literal meaning | character collection | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Title

The dictionary title combines zì 字 "character; script; writing; graph; word" and huì 彙 "gather together; assemble; collection; list". Early forms of the graph huì 彙 depicted a "hedgehog" (wèi 猬), and it was borrowed as a phonetic loan character for the word huì 匯 "gather together; collection", both of which, in the simplified character system, are 汇. In modern Chinese usage, zìhuì 字匯 or 字彙 means "glossary; wordbook; lexicon; dictionary; vocabulary; (computing) character set" (Wenlin 2016).

English translations of Zihui include "Compendium of Characters" (Creamer 1992), "Collection of Characters" (Zhou and Zhang 2003), "The Comprehensive Dictionary of Chinese Characters" (Yong and Peng 2008), and "Character Treasure" (Ulrich 2010)

Text

The Zihui dictionary comprises 14 volumes (巻), with a comprehensive and integrated format that many subsequent Chinese dictionaries followed.

Volume 1 contains the front matter, including Mei Yingzuo's preface dated 1615, style guide, and appendices. For instance, the "Sequences of Strokes" shows the correct stroke order, which is useful for students, "Ancient Forms" uses early Chinese script styles to explain the six Chinese character categories, and "Index of Difficult Characters" lists graphs whose radicals were difficult to identify (Yong and Peng 2008: 287-288).

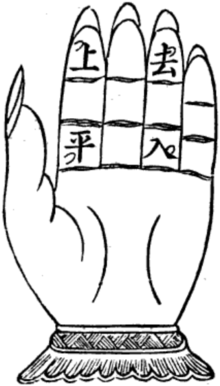

Volume 14 encompasses the back matter, with three main appendices. "Differentiation" lists 473 characters with similar forms but different pronunciations and meanings, such as 刺 and 剌 or 段 and 叚. "Rectification" corrects misunderstandings of 68 characters commonly used in contemporary printed books. "Riming" gives rime tables intended to explain the four tones of Middle Chinese and fanqie pronunciation glosses (Yong and Peng 2008: 287). Note that the above image of early Zihui dictionaries shows the traditional hand representation of the four tone classes.

The main body of the Zihui dictionary is divided into 12 volumes (2-13) called ji (集, collections) and numbered according to the twelve Earthly Branches. Each one begins with a grid diagram showing all the radicals included in the volume and their page numbers. This reference guide to the volumes made looking up characters more convenient than in the previous dictionaries (Yong and Peng 2008: 287).

The Zihui included 33,179 head character entries, most of which were from Song Lian's 1375 Hongwu zhengyun (洪武正韻, Hongwu Dictionary of Standard Rhymes). The entries included common characters used in the Chinese classics and some popular or nonstandard characters (súzì 俗字), both contemporary and early (Yong and Peng 2008: 287). Mei Yingzuo made his dictionary more easily accessible to the general literate public by using the current regular script form of characters. Beginning with the Shuowen jiezi, earlier Chinese dictionaries were arranged according to radicals written in the obsolete seal script (Norman 1988: 172).

The basic format of each Zihui character entry comprised first the pronunciations including variants, and then the definitions, giving the primary meaning followed by common and extended meanings. In addition to using the traditional fanqie spelling, Mei indicated pronunciation with a commonly used homophonous character, no doubt in recognition of the fact that it was "almost impossible for the average reader to derive correct current readings from Tang dynasty fanqie" (Norman 1988: 172). Definitions are for the most part brief and readily understandable, and reference to a text is almost always given by way of examples, generally from ancient books and partly from colloquial language. Zihui innovations in dictionary format, such as the arrangement of meanings, the use of plain language, and usage examples from informal language, made the book "exceptional at the time" (Yong and Peng 2008: 287).

The best-known lexicographical advances in Mei Yingzuo's Zihui are reducing the unwieldy Shuowen Jiezi 540-radical system for collating Chinese characters into the more legical 214-radical system, and arranging graphs belonging to a single radical according to the number of residual strokes, making finding character entries a relatively simple matter (Norman 1988: 171). To illustrate the inefficiencies of the Shuowen Jiezi system, only a few characters are listed under some radicals. For instance, its "man radical" 男, which compounds the modern "field radical" 田 and the "power radical" 力, only lists three: nan 男 ("man; male"), sheng 甥 ("nephew; niece"), and jiu 舅 ("uncle; brother in law"). In contrast, the Zihui eliminates the "man radical" and lists nan 男 under the "power radical", sheng 甥 under the "life radical" 生, and jiu 舅 under the "mortar radical" 臼. The 214 radicals are arranged according to stroke number, from the single-stroke "one radical" 一 to the seventeen-stroke "flute radical" 龠. The Zihui character entries are arranged according to the stroke number left after subtracting the respective radical, for instance, the characters under the "mouth radical" 口 begin with 卟, 古, and 句 and end with 囔, 囕, and 囖. This "radical-and-stroke" system remains one of the most common forms of Chinese lexicographic arrangement today,

History

With the possible exception of the 1324 Zhongyuan Yinyun, there were few advances in Chinese lexicography between the sixth and seventeenth centuries. Many dictionaries prior to the Ming Dynasty were modeled on the Shuowen Jiezi 540-radical format, and new dictionaries were generally no more than minor revisions and enlargements of older works. Mei Yingzuo's Zihui represents the "first important lexicographic advance" after this long period. He greatly simplified and rationalized the traditional set of radicals, introduced the principle of indexing graphs according to the number of residual strokes, and wrote characters in contemporary regular script instead of ancient seal script. The importance of Mei's innovations is confirmed by the fact that they were promptly imitated by other Ming and Qing period dictionaries (Norman 1988: 172).

The Zihui also formed the basis for the Zhengzitong, written and originally published by Zhang Zilie (張自烈) as the 1627 Zihui bian (字彙辯; "Zihui Disputations") supplemental correction to the Zihui, then purchased by Liao Wenying (廖文英) and republished as the 1671 Zhengzitong. Another Qing dynasty scholar Wu Renchen published the 1666 Zihui bu (字彙補 "Zihui supplement"). The most important of the works based on the Zihui model was undoubtedly the 1716 Kangxi Zidian, which soon became the standard dictionary of Chinese characters, and continues to be used widely today (Norman 1988: 172). After the Kangxi Zidian adopted Mei's 214-radical system, they have been known as the Kangxi radicals rather than "Zihui radicals".

Innovations

The author Thomas Creamer says Mei Yingzuo's Zihui was "one the most innovative Chinese dictionaries ever compiled" and it "changed the face of Chinese lexicography" (1992: 116).

The best-known lexicographical advances in the Zihui are reducing the unwieldy Shuowen Jiezi 540-radical system for collating Chinese characters into the more logical 214-radical system, and arranging graphs belonging to a single radical according to the number of residual strokes, making finding character entries a relatively simple matter (Norman 1988: 171). To illustrate the inefficiencies of the Shuowen Jiezi system, only a few characters are listed under some radicals. For instance, its "man radical" 男, which compounds the modern "field radical" 田 and the "power radical" 力, only lists three: nan 男 ("man; male"), sheng 甥 ("nephew; niece"), and jiu 舅 ("uncle; brother in law"). In contrast, the Zihui eliminates the "man radical" and lists nan 男 under the "power radical", sheng 甥 under the "life radical" 生, and jiu 舅 under the "mortar radical" 臼. The 214 radicals are arranged according to stroke number, from the single-stroke "one radical" 一 to the seventeen-stroke "flute radical" 龠. The Zihui character entries are arranged according to the stroke number left after subtracting the respective radical, for instance, the characters under the "mouth radical" 口 begin with 卟, 古, and 句 and end with 囔, 囕, and 囖. This "radical-and-stroke" system remains one of the most common forms of Chinese lexicographic arrangement today.

The Chinese scholar Zou Feng (邹酆) lists four major lexicographical format innovations that Mei Yingzuo established in the Zihui, and which have been used in many dictionaries up to the present day (1983, Yong and Peng 2008: 289-290). First, the Zihui includes both formal seal script and clerical script as well as informal regular script characters, and gives the latter more significance than previously. Second, character entry presentation is improved by including both fanqie and homophonic phonetic notation, initiating a "more scientific format" for displaying definitions from original through extended meanings, using the label 〇 to display characters with multiple pronunciations and meanings, and indicating characters that have multiple parts of speech, all of which are standard format elements in modern Chinese dictionaries. Third, radicals and character entries are classified in a more logical manner, as explained above. Fourth, the Zihui was the first Chinese dictionary to integrate the main body and appendices into one whole, thus improving practicality for the user.

References

- Creamer, Thomas B. I. (1992), "Lexicography and the history of the Chinese language", in History, Languages, and Lexicographers, (Lexicographica, Series maior 41), ed. by Ladislav Zgusta, Niemeyer, 105-135.

- Norman, Jerry (1988), Chinese, Cambridge University Press.

- Ulrich, Theobald (2010), Zihui 字彙 "Collection of Characters", Chinaknowledge

- Yong, Heming and Jing Peng (2008), Chinese Lexicography: A History from 1046 BC to AD 1911, Oxford University Press.

- Zhou Youguang 周有光 (2003), The Historical Evolution of Chinese Languages and Scripts, tr. by Zhang Liqing 張立青 National East Asian Languages Resource Center, Ohio State University.

- Zou Feng 邹酆 (1983), "Innovations in the Compilation of The Comprehensive Dictionary of Chinese Characters", 《字集》在字典编纂法上的创新, Lexicographical Studies 辞书研究 5: 34–39, Shanghai Lexicographical Press. (in Chinese)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zihui. |

- 字彙, Zihui, Internet Archive (in Chinese)

- 字彙補, Zihui bu, Chinese Text Project (in Chinese)

- The 214 Radicals 部首, ChinaKnowledge