Variant Chinese character

Variant Chinese characters (simplified Chinese: 异体字; traditional Chinese: 異體字; pinyin: yìtǐzì; Kanji: 異体字; Hepburn: itaiji; Korean: 이체자; Hanja: 異體字; Revised Romanization: icheja) are Chinese characters that are homophones and synonyms. Almost all variants are allographs in most circumstances, such as casual handwriting. Some contexts require the usage of certain variants, such as in textbook editing.

| Variant character | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Differences for the same Unicode character in regional versions of Source Han Sans | |||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 異體字 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 异体字 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | different form character | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 又體 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 又体 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | also form | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 或體 | ||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 或体 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | or form | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Third alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||

| Chinese | 重文 | ||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | repeated writing | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||

| Hangul | 이체자 | ||||||||||||

| Hanja | 異體字 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||

| Hiragana | いたいじ | ||||||||||||

| Kyūjitai | 異體字 | ||||||||||||

| Shinjitai | 異体字 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

Regional standards

Variant Chinese characters exist within and across all regions where Chinese characters are used, whether Chinese-speaking (mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Singapore), Japanese-speaking (Japan), or Korean-speaking (North Korea, South Korea). Some of the governments of these regions have made efforts to standardize the use of variants, by establishing certain variants as standard. The choice of which variants to use has resulted in some divergence in the forms of Chinese characters used in mainland China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. This effect compounds with the sometimes drastic divergence in the standard Chinese character sets of these regions resulting from the character simplifications pursued by mainland China and by Japan.

The standard character forms of each region are described in:

- The List of Commonly Used Characters in Modern Chinese for mainland China

- The List of Graphemes of Commonly-Used Chinese Characters for Hong Kong

- The Standard Form of National Characters for Taiwan

- The list of Jōyō kanji for Japan

- The Kangxi Dictionary (de facto) for Korea

Origins of variants

Character forms that are most orthodox are known as orthodox characters (Chinese: 正字; pinyin: zhèngzì) or Kangxi Dictionary form (Chinese: 康熙字典體; pinyin: Kāngxī zìdiǎn tǐ), as the forms found in the Kangxi dictionary are usually the ones consider to be orthodox, at least by late Imperial China standards. Variants that are used in informal situations are known as popular characters (Chinese: 俗字; pinyin: súzì; Revised Romanization: sokja; Hepburn: zokuji). Some of these are longstanding abbreviations or alternate forms that became the basis for the Simplified Character set promulgated by the People's Republic of China. For example, 痴 is the popular variant, whereas 癡 is the orthodox form of the character meaning 'stupid; demented'. In this case, two different phonetic elements were chosen to represent the same sound. In other cases, the differences between the orthodox form and popular form are merely minor distinctions in the length or location of strokes, whether certain strokes cross, or the presence or absence of minor inconspicuous strokes (dots). These are often not considered true variant characters but are adoptions of different standards for character shape. In mainland China, these are called 新字形 ('new character shape', typically a simplified popular form) and 旧字形 ('old character shape', typically the Kangxi dictionary form). For instance, 述 is the new form of the character with traditional orthography 述 'recount; describe'. As another example, 吴 'a surname; name of an ancient state' is the 'new character shape' form of the character traditionally written 吳.

Variant graphs also sometimes arise during the historical processes of liding (隸定) and libian (隸變), which refer to conversion of seal script to clerical script by simple regularization and linearization of shape (liding, lit. 'clerical fixing') or more significant omissions, additions, or transmutations of graphical form (libian, lit. 'clerical changing'). For instance, the small seal script character for 'year' was converted by more conservative liding to a clerical script form that eventually led to the variant 秊, while the same character, after undergoing the more drastic libian, gave rise to a clerical script form that eventually became the orthodox 年. A similar divergence in the regularization process led to two characters for 'tiger', 虎 and 乕.

There are variants that arise through the use of different radicals to refer to specific definitions of a multisemous character. For instance, the character 雕 could mean either 'certain types of hawk' or 'carve; engrave.' For the former, the variant 鵰 ('bird' radical) is sometimes employed, while for the latter, the variant 琱 ('jade' radical) is sometimes used.

In rare cases, two characters in ancient Chinese with similar meanings can be confused and conflated if their modern Chinese readings have merged, for example, 飢 and 饑, are both read as jī and mean 'famine; severe hunger' and are used interchangeably in the modern language, even though 飢 meant 'insufficient food to satiate', and 饑 meant 'famine' in Old Chinese. The two characters formerly belonged to two different Old Chinese rime groups (脂 and 微 groups, respectively) and could not possibly have had the same pronunciation back then. A similar situation is responsible for the existence of variant forms of the preposition with the meaning 'in; to', 于 and 於 in the modern (traditional) orthography. In both cases described above, the variants were merged into a single simplified Chinese character, 饥 and 于, by the mainland (PRC) authorities.

Usage in computing

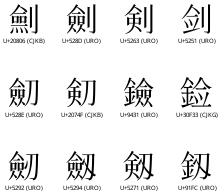

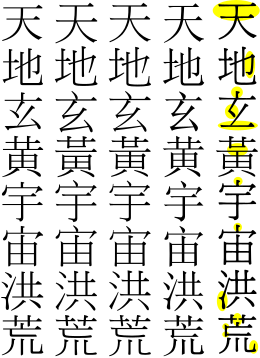

Unicode deals with variant characters in a complex manner, as a result of the process of Han unification. In Han unification, some variants that are nearly identical between Chinese-, Japanese-, Korean-speaking regions are encoded in the same code point, and can only be distinguished using different typefaces. Other variants that are more divergent are encoded in different code points. On web pages, displaying the correct variants for the intended language is dependent on the typefaces installed on the computer, the configuration of the web browser and the language tags of web pages. Systems that are ready to display the correct variants are rare because many computer users do not have standard typefaces installed and the most popular web browsers are not configured to display the correct variants by default. The following are some examples of variant forms of Chinese characters with different code points and language tags.

| Different code points, China language tag | Different code points, Taiwan language tag | Different code points, Hong Kong language tag | Different code points, Japanese language tag | Different code points, Korean language tag |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 戶戸户 | 戶戸户 | 戶戸户 | 戶戸户 | 戶戸户 |

| 爲為为 | 爲為为 | 爲為为 | 爲為为 | 爲為为 |

| 強强 | 強强 | 強强 | 強强 | 強强 |

| 畫畵画 | 畫畵画 | 畫畵画 | 畫畵画 | 畫畵画 |

| 線綫线 | 線綫线 | 線綫线 | 線綫线 | 線綫线 |

| 匯滙 | 匯滙 | 匯滙 | 匯滙 | 匯滙 |

| 裏裡 | 裏裡 | 裏裡 | 裏裡 | 裏裡 |

| 夜亱 | 夜亱 | 夜亱 | 夜亱 | 夜亱 |

| 龜亀龟 | 龜亀龟 | 龜亀龟 | 龜亀龟 | 龜亀龟 |

The following are some examples of variant forms of Chinese characters with the same code points and different language tags.

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Graphemic variants

Some variants are not allographic. For a set of variants to be allographs, someone who could read one should be able to read the others, but some variants cannot be read if one only knows one of them. An example is 搜 and 蒐, where someone who is able to read 搜 might not be able to read 蒐. Another example is 㠯, which is a variant of 以, but some people who could read 以 might not be able to read 㠯.