Battle of Haguenau (1793)

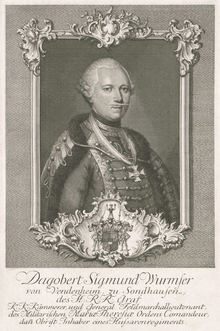

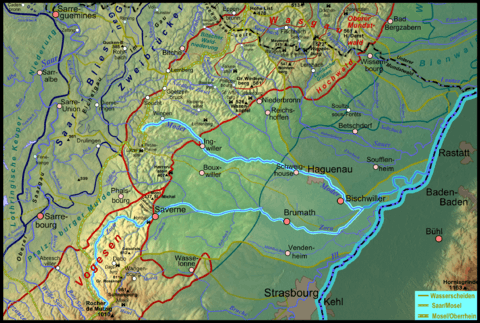

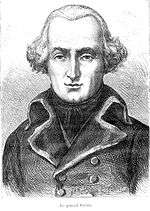

The Battle of Haguenau [1][2] (18 November – 22 December 1793) saw a Republican French army commanded by Jean-Charles Pichegru mount a persistent offensive against a Coalition army under Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser during the War of the First Coalition. In late November, Wurmser pulled back from his defenses behind the Zorn River and assumed a new position along the Moder River at Haguenau. After continuous fighting, Wurmser finally withdrew to the Lauter River after his western flank was turned in the Battle of Froeschwiller on 22 December. Haguenau is a city in Bas-Rhin department of France, located 29 kilometres (18 mi) north of Strasbourg.

| Battle of Haguenau (1793) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of War of the First Coalition | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 57,000 | 41,000 | ||||||

Consisting of troops from Habsburg Austria, Hesse-Kassel and Electoral Bavaria, plus French Royalists, the Coalition army broke through the French frontier defenses in the First Battle of Wissembourg on 13 October 1793 and overran Alsace as far as the Zorn River. The French government reacted to the emergency by appointing Pichegru to lead the Army of the Rhine and urging it to attack. Beginning on 18 November, Pichegru ordered continual attacks on the Coalition lines which slowly forced Wurmser's army back. The Battle of Berstheim was a notable action during the French offensive. Unfortunately for Wurmser, a Prussian army failed to pin down Lazare Hoche's Army of the Moselle to the west. When Hoche began to put pressure on the Coalition right wing, Wurmser was unable to spare sufficient troops to resist the new threat because of Pichegru's relentless frontal attacks. The next combat was the Second Battle of Wissembourg on 25–26 December.

Background

In the First Battle of Wissembourg on 13 October 1793, the Coalition army under Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser assaulted and defeated the French Army of the Rhine led by Jean Pascal Carlenc. The Coalition mustered 33,599 infantry and 9,635 cavalry while the French counted 45,312 foot soldiers and 6,278 horsemen. The mostly Austrian army with allied Hessians, Swabians and French Émigrés suffered 1,800 casualties while inflicting losses of 2,000 killed and wounded on the French. In addition the Coalition captured 1,000 soldiers, 31 guns and 12 colors.[3] Another source gave a total of 43,185 Coalition troops and 34,400 French. A number of French officers behaved poorly. Right Wing commander Paul-Alexis Dubois retreated unnecessarily while Carlenc refused to order a counterattack without authorization from French political officials. The French army fell back south toward Strasbourg.[4]

On 23 October 1793, the chilling Louis Antoine de Saint-Just and his colleague Philippe-François-Joseph Le Bas arrived as representatives on mission with extraordinary powers. They immediately sent for Jean-Charles Pichegru, who commanded troops on the upper Rhine River, to lead the army. They stopped the practice of officers and men visiting Strasbourg and insisted on strict discipline. They also purged the army staff of noblemen and instituted a harsh regime of shooting and sacking officers. Meanwhile, a gang of revolutionaries dragged a guillotine from village to village visiting retribution on supposed enemies. The gang's activities became so extreme that even Saint-Just had to call for a stop.[5] On 29 October 1793, Pichegru arrived at Strasbourg to assume command of the Army of the Rhine.[6] Carlenc was dismissed and arrested, though he avoided the guillotine.[7]

On 30th the army's organization included the Advanced Guard under Jean Baptiste Meynier, Right Wing under Dubois, Left Wing under Claude Ferey and Center under Louis Dominique Munnier. Jean François Ravel de Puycontal led the artillery and pioneers. In the following order of battle, the numbered regular army infantry units are in demi brigades and the battalions named after their departments are National Guard units. The nominal total was 57,369 men while the number of soldiers fit for duty was 42,420.[8]

Ravel's command comprised the 5th Artillery Regiment, the 1st Battalion of the Bas-Rhin, one battalion of Pioneers and 22 Guides. The Advanced Guard consisted of the 6th, 12th, 48th and 105th Line Infantry, 1st and 2nd Grenadier Battalions, the Chasseurs du Rhin, the 1st Battalions of the Corrèze and Jura and the 2nd Battalion of the Lot-et-Garonne. Jean Claude Loubat de Bohan commanded a cavalry brigade that comprised the 8th, 11th and 17th Dragoon, 7th Hussar, and 8th and 10th Chasseurs à Cheval Regiments. The Right Wing included the 37th and 40th Line and 11th Light Infantry, the 1st Battalion of the Pyrenées-Orientales, the 3rd Battalions of the Charente-Inférieur, Haute-Saône and Rhône-et-Loire, the 5th Battalion of the Ain, the 7th Battalion of the Haute-Saône and a free company.[8]

The Left Wing counted the 13th and 27th Line and 7th Light Infantry, the 1st Battalions of the Haute-Rhin, Haute-Saône, Indre and Vosges, the 2nd Battalion of the Rhône-et-Loire, the 3rd Battalions of the Indre-et-Loire and Haut-Rhin, the 4th Battalions of the Jura and Seine-et-Loire and the 10th Battalion of the Vosges, the 7th Chasseurs à Cheval and one squadron each of the Gendarmes and 2nd Cavalry Regiments. In the Center, Jean Nicolas Mequillet's brigade consisted of the 3rd and 30th Line Infantry, the 1st Battalion of the Ain, the 3rd Battalions of the Ain and Doubs and the 12th Battalion of the Jura. Augustin-Joseph Isambert's brigade was made up of the 46th Line Infantry, the 2nd Battalions of the Eure-et-Loire and Puy-de-Dôme, the 3rd Battalion of the Bas-Rhin and the 11th Battalion of the Doubs. Paul Louis Darigot de la Ferrière's brigade had two battalions of the 93rd Line Infantry, the 1st Battalion of the Lot-et-Garonne, the 2nd Grenadier Battalion of the Rhône-et-Loire and the 5th Battalion of the Seine-et-Oise.[8]

Saint-Just declared that "for the good of the army" a general needed to be executed as an example. Because he had retreated before a small body of Austrian horsemen, Isambert was chosen as the example.[9] The 60-year-old Isambert died on 9 November.[10] Isambert was one of 17 generals executed in 1793; in the following year the number would almost quadruple.[11] Dubois was replaced in command of the Right Wing. Louis Desaix was appointed to lead the Advance Guard on the far right while Pierre Marie Barthélemy Ferino took over the Left Wing from Ferey who reassumed command of his brigade.[7] The senior division commander Munnier was temporarily put in charge of the army but when it looked like the appointment might be permanent, he simply stopped communicating any orders. He was of course arrested and sent to Paris, but he managed to escape execution.[12]

After Wissembourg, the Left Wing retreated to the Zorn River at Hochfelden.[7] On 14 October, a 4,700-man Coalition force led by Austrian Franz von Lauer undertook the Siege of Fort-Louis. The 4,500-man garrison under Michel Durand manned the fort's 111 artillery pieces. The defenders included three regular and four National Guard battalions. The attacking force counted three Electoral Bavarian battalions, two Hesse-Darmstadt battalions, one battalion and two Hussar squadrons of Austrians and 55 siege cannons. The fort surrendered on 14 November and the French became prisoners of war.[13] On 22 October 1793 Austrian Friedrich Freiherr von Hotze's troops attacked Ferino's positions at Saverne. With the help of six battalions of reinforcements from the Army of the Moselle, Ferino drove off the Coalition force. It is probable that Nicolas Oudinot won a promotion to chef de brigade (colonel) on this occasion.[14] On the 27th, the Austrians attacked Desaix's division but the capable general fought his division well and held his ground.[7]

Battle

Starting on 18 November, Pichegru began a series of attacks on the Coalition lines. Wurmser was Alsatian and fiercely resisted being driven out of his homeland. By this time the French division commanders were Desaix on the right, Claude Ignace François Michaud on the right-center, Ferino on the left-center and Pierre Augustin François de Burcy on the left. Michaud assaulted the woods near Brumath but his and Desaix's divisions were turned back. On the left, Burcy and Ferino's divisions drove back Hotze and threatened Bouxwiller. Knowing that the allied Prussian army of Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel was withdrawing into winter quarters on his right flank, Wurmser ordered a retreat to positions closer to the Moder River and Haguenau.[15]

Burcy followed up the Coalition withdrawal to Gundershoffen, where, on 26 November, the representatives ordered Burcy to attack a strong Coalition redoubt. When Burcy hesitated, the politicians threatened to arrest him. He attacked with one brigade, was repulsed, attacked again with the last intact unit and was killed while leading his troops. The soldiers retreated to Uttenhoffen, leaving a second brigade isolated in the Mietesheim forest. Forgotten for two days amid the battle, this brigade was attacked on 28 November and held its position largely thanks to the leadership of Oudinot. Burcy's replacement was his chief of staff Jacques Maurice Hatry who ordered the brigade to pull back into line that afternoon. Hatry attacked the Gundershoffen redoubt again on 1 December and was repulsed.[16]

Ferino's division fought its way across the Zorn to the village of Mommenheim. Here the French were opposed by Siegfried von Kospoth's Austrians on their right and the French Royalist Army of Condé on their left. After Ferino's left brigade under Ferey was repulsed by the Royalists and lost some cannons, Jean Ignace Pierre was appointed to lead the unit. Ferino directed Pierre to clear the village of Berstheim which the émigrés had fortified. On 27 and 28 November Pierre proved unable to carry out this assignment so Laurent Gouvion Saint-Cyr offered to capture and hold the village. On 2 December Saint-Cyr rapidly seized the village with two battalions under the noses of the astounded Royalists. However, Pierre in his haste advanced his troops in poor order and the émigrés took cruel advantage of his mistake. The Royalist cannons suddenly opened up on the Republicans, causing confusion. Part of the Royalist cavalry routed Pierre's brigade, capturing its artillery, while another part charged Ferino's cavalry.[17] At length, the French cavalry recovered a few of the lost guns, but Saint-Cyr was compelled to withdraw from Berstheim. The combat ended when some Austrian troops arrived to help. Louis Henri, Duke of Bourbon was wounded in the hand.[18]

We saw the plain suddenly covered by an immense number of soldiers scattered over the ground, who, starting from the crest of the heights occupied by the Republicans, made at full speed for the village of Berstheim. Hardly had they got within pistol-shot than they formed in squads, even in battalions, to rush to the attack of this post, which had become so important to them. Our eyes had hardly time to observe this maneuver, whose object we had not yet grasped, when Berstheim was in the power of the Republicans. This bold stroke in an instant nullified all the effect of our artillery. Homage to the soldiers of our country, perhaps the only ones in Europe capable of executing such an enterprise![19]

Pichegru ordered Saint-Cyr, a mere lieutenant colonel, to take command of Pierre's brigade on 6 December. After his brigade was reinforced, Saint-Cyr moved on Berstheim on the 8th. The Royalists taunted the Republicans, asking if they were bringing them more artillery to capture. Saint-Cyr advanced his light troops to the edge of the village before pulling back.[18] The émigré infantry under General Gelb and cavalry led by Louis Antoine, Duke of Enghien rushed in pursuit. On this day the Royalists were mauled and Gelb was killed while Enghien's coat was riddled with bullet holes. The Duke of Bourbon narrowly escaped death. When he cut his way into the 19th Line Infantry,[20] a Republican officer recognized him and saluted with his sword rather than running him through.[21] On 9 December, Saint-Cyr advanced on Berstheim again and was surprised to find that the Royalists had retired. This move was part of Wurmser's deliberate withdrawal to the Moder.[20]

Once established in his Moder defenses, Wurmser repelled assault after assault by Pichegru. The French commander reinforced Desaix on the right in an effort to seize Bischwiller. Michaud hammered at the Coalition forts north of Brumath while Ferino attacked southwest of Haguenau. Off to the west, Hatry's division repeatedly tried to cross the Zinzel River at Mertzwiller but was driven back each time. Despite being able to hold off the frontal attacks of the Army of the Rhine, Wurmser became anxious about his western flank.[21]

In the Battle of Kaiserslautern on 28 to 30 November 1793, the Duke of Brunswick repulsed the Army of the Moselle under Lazare Hoche.[22] Thwarted there, Hoche began shifting his army to the right. Already on 23 November Philippe-Joseph Jacob's division reached Niederbronn-les-Bains on the edge of the Vosges, behind Wurmser's right flank. Hoche feinted at Kaiserslautern again but in actuality, he ordered his left wing to fortify Pirmasens and Blieskastel while throwing his weight to the east. On 5 December, a second division arrived near Niederbronn and its commander Alexandre Camille Taponier assumed control of both divisions.[23]

Taponier's 12,000 troops began fighting their way down the Niederbronn valley on 8 December.[24] On 12 December, Jean Grangeret's 10,000-man division joined the other Army of Moselle troops. Pichegru and Hoche met at Niederbronn on the 14th to arrange for their two armies to act together.[23] A series a battles ensued in which François Joseph Lefebvre took command of Jacob's division and Jean-de-Dieu Soult led an independent detachment. The Battle of Froeschwiller ended on 22 December when the Army of the Moselle captured Froeschwiller, Woerth and Reichshoffen. This event prompted Wurmser to abandon Haguenau and begin retreating to the Lines of Wissembourg on the Lauter River, closely pursued by the Army of the Rhine.[25]

Results

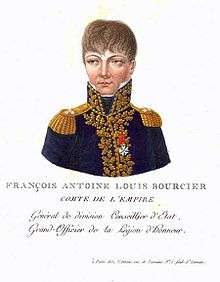

By continually attacking while shrugging off frequent repulses, the French wore out their enemies rather than defeating them.[23] Pichegru was able to use the dangerous Saint-Just and La Bas for his purposes. He also selected good military advisers.[15] These men were Barthélemy Louis Joseph Schérer, his successor in command of the Upper Rhine Division, Desaix, Claude Juste Alexandre Legrand and his chief of staff François Antoine Louis Bourcier. Pichegru also had the courage to protect Desaix from dismissal for the crime of being a nobleman.[26]

All through the subsequent operations, which ended in the relief of Landau, he [Pichegru] kept his hold on the enemy, and, though the success is credited to Hoche, it must always be remembered how much depended on the support given by the Rhine.[14]

The next action was the Second Battle of Wissembourg on 25 and 26 December 1793. The Coalition forces were beaten, the Austrians retreating to the east bank of the Rhine and the Prussians falling back toward Mainz.[27] The French were able to end the Siege of Landau which had begun on 20 August 1793.[28]

Notes

- Urban, Sylvanus (1830). "Obituary: Duke of Bourbon". The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle from July to December 1830. 100. London: J.B. Nichols and Son. p. 272.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: a guide to 8,500 battles from antiquity through the 21st century. 2. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 426. ISBN 0-313-33538-9.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. p. 58. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Phipps (2011), pp. 76-77

- Phipps (2011), p. 81

- Phipps (2011), p. 74

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. p. 40. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1980). The Art of War in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. p. 112. ISBN 0-253-31076-8.

- Broughton, Tony (2001). "French Infantry Regiments and the Colonels who Led Them: 1791-1815: 31e-40e Regiments". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- Rothenberg (1980), p. 36

- Phipps (2011), p. 70

- Smith (1998), p. 61

- Phipps (2011), p. 85

- Phipps (2011), p. 91

- Phipps (2011), p. 92

- Phipps (2011), p. 93

- Phipps (2011), p. 94

- Phipps (2011), p. 117

- Phipps (2011), p. 95

- Phipps (2011), p. 96

- Smith (1998), pp. 62-63

- Phipps (2011), p. 97

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Battle of Froeschwiller, 18-22 December 1793". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Phipps (2011), pp. 98-99

- Phipps (2011), p. 83

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Battle of Wissembourg or The Geisberg, 25-26 December 1793". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Smith (1998), p. 65

References

- Broughton, Tony (2001). "French Infantry Regiments and the Colonels who Led Them: 1791-1815: 31e-40e Regiments". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- Jaques, Tony (2007). Dictionary of Battles and Sieges: a guide to 8,500 battles from antiquity through the 21st century. 2. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33538-9.

- Phipps, Ramsay Weston (2011). The Armies of the First French Republic: Volume II The Armées du Moselle, du Rhin, de Sambre-et-Meuse, de Rhin-et-Moselle. USA: Pickle Partners Publishing. ISBN 978-1-908692-25-2.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Battle of Froeschwiller, 18-22 December 1793". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Rickard, J. (2009). "Battle of Wissembourg or The Geisberg, 25-26 December 1793". historyofwar.org. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Rothenberg, Gunther E. (1980). The Art of War in the Age of Napoleon. Bloomington, Ind.: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-31076-8.

- Smith, Digby (1998). The Napoleonic Wars Data Book. London: Greenhill. ISBN 1-85367-276-9.

- Urban, Sylvanus (1830). "Obituary: Duke of Bourbon". The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle from July to December 1830. 100. London: J.B. Nichols and Son. p. 272.