Jagannath

Jagannath (Sanskrit: जगन्नाथ, ISO: Jagannātha; lit. ''lord of the universe'') is a deity worshipped in regional traditions of Hinduism in India and Bangladesh. Jagannath is considered a form of Vishnu.[1][2] He is part of a triad along with his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra. To most Vaishnava Hindus, Jagannath is an abstract representation of Krishna; to some Shaiva and Shakta Hindus, he is a symmetry-filled tantric representation of Bhairava; to some Buddhists, he is a symbolic representation of the Buddha in the Buddha-Sangha-Dhamma triad; to some Jains, his name and his festive rituals are derived from Jeenanath of Jainism tradition.[3]

| Jagannath | |

|---|---|

Shri Jagannath Mahaprabhu | |

| Affiliation | Abstract form of Maha Vishnu and Krishna |

| Abode | Mount Nila |

| Weapon | Sudarshana Chakra, Panchajanya |

| Mount | Garuda |

| Personal information | |

| Siblings | Balabhadra & Subhadra |

| Consort | Mahalaxmi |

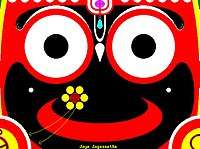

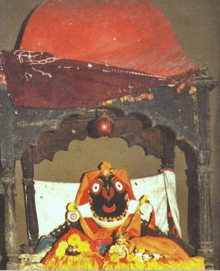

The icon of Jagannath is a carved and decorated wooden stump with large round eyes and a symmetric face, and the icon has a conspicuous absence of hands or legs. The worship procedures, sacraments and rituals associated with Jagannath are syncretic,[3] and include rites that are uncommon in Hinduism.[4] Unusually, the icon is made of wood and replaced with a new one at regular intervals. The origin and evolution of Jagannath worship is unclear.[5] Some scholars interpret hymn 10.155.3 of the Rigveda as a possible origin, but others disagree and state that it is a syncretic deity with tribal roots.[5] His name does not appear in the traditional Dashavatara (ten avatars) of Vishnu,[6] though in certain Odia literature, Jagannath has been treated as the ninth avatar, as a substitute for or the equivalent of the Shakyamuni Buddha.[7]

Jagannath is considered a non-sectarian deity.[8][9][10] He is significant regionally in the Indian states of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Gujarat, Assam, Manipur and Tripura.[11] He is also significant to the Hindus of Bangladesh. The Jagannath temple in Puri, Odisha is particularly significant in Vaishnavism, and is regarded as one of the Char Dham pilgrimage sites in India.[12] The Jagannath temple is massive, over 61 metres (200 ft) high in the Nagara Hindu temple style, and one of the best surviving specimens of Kalinga architecture aka Odisha art and architecture.[13] It has been one of the major pilgrimage destinations for Hindus since about 800 CE.[13]

The annual festival called the Ratha yatra celebrated in June or July every year in eastern states of India is dedicated to Jagannath. His image, along with the other two associated deities, is ceremoniously brought out of the sacrosanctum (Garbhagriha) of his chief temple in Jagannath Puri (Oriya: Bada Deula). They are placed in a chariot which is then pulled by numerous volunteers to the Gundicha Temple, (located at a distance of nearly 3 km or 1.9 mi). They stay there for a few days, after which they are returned to the main temple. Coinciding with the Ratha Yatra festival at Puri, similar processions are organized at Jagannath temples throughout the world. During the festive public procession of Jagannath in Puri lakhs of devotees visit Puri to see Lord Jagganath in chariot.[14]

Etymology

Jagannath is a Sanskrit word, compounded of jagat meaning "universe" and nātha meaning "Master" or "Lord". Thus, Jagannath means "lord of the universe".[15][16]

— Surendra Mohanty, Lord Jagannatha: the microcosm of Indian spiritual culture[17]

In the Odia language, Jagannath is linked to other names, such as Jagā (ଜଗା) or Jagabandhu (ଜଗବନ୍ଧୁ) ("Friend of the Universe"). Both names derive from Jagannath. Further, on the basis of the physical appearance of the deity, names like Kālya (କାଳିଆ) ("The Black-coloured Lord", but which can also mean "the Timely One"), Darubrahman (ଦାରୁବ୍ରହ୍ମ) ("The Sacred Wood-Riddle"), Dāruēdebatā (ଦାରୁ ଦେବତା "The wooden god"), Chakā ākhi (ଚକା ଆଖି) or Chakānayan (ଚକା ନୟନ "With round eyes"), Cakāḍōḷā (ଚକା ଡୋଳା "with round pupils") are also in vogue.[18][19][20]

According to Dina Krishna Joshi, the word may have origins in the tribal word Kittung of the Sora people (Savaras). This hypothesis states that the Vedic people as they settled into tribal regions adopted the tribal words and called the deity Jagannath.[21] According to O.M. Starza, this is unlikely because Kittung is phonetically unrelated, and the Kittung tribal deity is produced from burnt wood and looks very different from Jagannath.[22]

Iconography

The icon of Jagannath in his temples is a brightly painted, rough-hewn log of neem wood.[23] The image consists of a square flat head, a pillar that represents his face merging with the chest. The icon lacks a neck, ears, and limbs, is identified by a large circular face symbolizing someone who is anadi (without beginning) and ananta (without end).[24] Within this face are two big symmetric circular eyes with no eyelids, one eye symbolizing the sun and the other the moon, features traceable in 17th-century paintings. He is shown with an Urdhva Pundra, the Vaishnava U-shaped mark on his forehead. His dark color and other facial features are an abstraction of the cosmic form of the Hindu god Krishna, states Starza.[25] In some contemporary Jagannath temples, two stumps pointing forward in hug-giving position represent his hands. In some exceptional medieval and modern era paintings in museums outside India, such as in Berlin states Starza, Jagannath is shown "fully anthropomorphised" but with the traditional abstract mask face.[25]

The typical icon of Jagannath is unlike other deities found in Hinduism who are predominantly anthropomorphic. However, aniconic forms of Hindu deities are not uncommon. For example, Shiva is often represented in the form of a Shiva linga. In most Jagannath temples in the eastern states of India, and all his major temples such as the Puri, Odisha, Jagannath is included with his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra. Apart from the principal companion deities, Jagannath icon shows a Sudarshana Chakra and sometimes under the umbrella cover of multiheaded Sesha Naga, both linking him to Vishnu. He was one of the introduction to Hinduism to early European explorers and merchants who sailed into Calcutta and ports of the Bay of Bengal. The Italian Odoric of Pordenone who was a Franciscan friar, visited his temple and procession in 1321 CE, and described him in the language of the Church. William Burton, visited his temple at Puri in 1633, spelled him as Jagarnat and described him to be "in a shape like a serpent, with seven hoods".[26]

When shown with Balabhadra and Subhadra, he is identifiable from his circular eyes compared to the oval or almond shape of the other two abstract icons. Further, his icon is dark, while Balabhadra's face is white, and Subhadra's icon is yellow. The third difference is the flat head of Jagannath icon, compared to semi-circular carved heads of the other two.[27][note 1] They are accompanied by the Sudarshana Chakra, the iconic weapon of Vishnu. It is approximately the same height as Balabhadra, is red in colour, carved from a wooden pillar and clothed, unlike its traditional representation as a chakra in other Vishnu temples.[28] Jagannath iconography, when he is depicted without companions, shows only his face, neither arms nor torso. This form is sometimes called Patita Pavana,[29] or Dadhi Vaman.[30]

The murtis of Jagannath, Balabhadra, Subhadra and Sudarshana Chakra are made of neem wood.[31] Neem wood is chosen because the Bhavishya Purana declares it to be the most auspicious wood from which to make Vishnu murtis.[26] The wood icon is re-painted every year before the Ratha-Yatra. It is replaced with a newly carved image every 12 or 19 years approximately, or more precisely according to the luni-solar Hindu calendar when its month of Asadha occurs twice in the same year.[32]

Attributes

Jagannath is considered an avatar (incarnation) of Vishnu.[33] Others consider him equivalent to the Hindu metaphysical concept of Brahman, wherein he then is the Avatarī, i.e., the cause and equivalence of all avatars and the infinite existence in space and time.[34] According to author Dipti Ray in Prataparudra Deva, the Suryavamsi King of Odisha:

In Prataparudradeva's time Odia poets accepted Sarala Dasa's idea and expressed in their literary works as all the Avataras of Vishnu (Jagannath) manifest from him and after their cosmic play dissolute (bilaya) in him (Jagannath). According to them Jagannath is Sunnya Purusa, Nirakar and Niranjan who is ever present in Nilachala to do cosmic play ... The five Vaishnavite Sakhas ["Comrades"] of Orissa during Prataparudradeva's time expounded in their works the idea that Jagannath (Purushottama) is Purna Brahman from whom other Avataras like Rama, Krishna, etc., took their birth for lilas in this universe and at the end would merge in the self of Purna Brahman.

— Dipti Ray[35]

In the Jagannath tradition, he has the attributes of all the avatars of Vishnu. This belief is celebrated by dressing him and worshipping him as different avatars on special occasions.[36] However he is most frequently identified with Krishna, the eighth avatar of Vishnu.[37] The Puranas relate that the Narasimha Avatar of Vishnu appeared from a wooden pillar. It is therefore believed that Jagannath is worshipped as a wooden murti or Daru Brahma with the Shri Narasimha hymn dedicated to the Narasimha Avatar.[38] Every year in the month of Bhadra, Jagannath is dressed and decorated in the form of the Vamana avatar of Vishnu.[34] Jagannath appeared in the form of Rama, another avatar of Vishnu, to Tulsidas, who worshipped him as Rama and called him Raghunath during his visit to Puri in the 16th century.[39][40]

Tantric deity

Outside of Vaishnava tradition, Jagannath is considered the epitome of Tantric worship.[41] The symmetry in iconography, the use of mandalas and geometric patterns in its rites support the tantric connection proposal.[3] Jagannath is venerated as Bhairava or Lord Shiva, the consort of Goddess Vimala, by Shaivites and Shakta sects.[42] The priests of Jagannath Temple at Puri belong to the Shakta sect, although the Vaishnava sect's influence predominates.[43] As part of the triad, Balabhadra is also considered to be Shiva and Subhadra, a manifestation of Durga or Laksmi.[44] In the Markandeya Purana the sage Markandeya declared that Purushottama Jagannath and Shiva are one.[45] Jagannath in his Hathi Besha (elephant form) has been venerated by devotees like Ganapati Bhatta of Maharashtra as the God Ganesh.[39]

Origins: alternative theories

Vedic origin of Jagannath

In hymn 10.155 of the Rig veda, there is mention of a Daru (wooden log) floating in the ocean as apurusham.[5][46] Acharya Sayana interpreted the term apurusham as same as Purushottama and this Dara wood log being an inspiration for Jagannath, thus placing the origin of Jagannath in 2nd millennium BCE. Other scholars refute this interpretation stating that the correct context of the hymn is "Alaxmi Stava" of Arayi.[5]

According to Bijoy Misra, Puri natives do call Jagannatha as Purushottama, consider driftwood a savior symbol, and later Hindu texts of the region describe the Supreme Being as ever present in everything, pervasive in all animate and inanimate things. Therefore, while the Vedic connection is subject to interpretation, the overlap in the ideas exist.[13]

Buddhist origins

The Buddhist origins theory relies on circumstantial evidence and colonial era attempts to reconcile empirical observations with the stereotypical assumptions about Indian religions. For example, there exists an unexamined relic in the Jagannath shrine in Puri,[48] and the local legends state that the shrine relic contains a tooth of the Buddha – a feature common to many cherished Theravada Buddhist shrines in and outside of India.[13][49] Other legends state that the shrine also contains bones of the human incarnation of the Hindu god Krishna, after he was accidentally killed by a deer hunter. However, in the Hindu tradition, a dead body is cremated, ashes returned to nature, and the mortal remains or bones are not preserved or adored.[50] In Buddhism, preserving skeletal parts such as "Buddha's tooth" or relics of dead saints is a thriving tradition. The existence of these legends, state some scholars such as Stevenson, suggests that Jagannath may have a Buddhist origin.[50] However, this is a weak justification because some other traditions such as those in Jainism and tribal folk religions too have had instances of preserving and venerating relics of the dead.[48]

A circumstantial evidence that links Jagannath deity to Buddhism is the Ratha-Yatra festival for Jagannath, the stupa-like shape of the temple and a dharmachakra-like discus (chakra) at the top of the spire. The major annual procession festival has many features found in the Mahayana Buddhism traditions.[13] Faxian (c. 400 CE[51]), the ancient Chinese pilgrim and visitor to India wrote about a Buddhist procession in his memoir, and this has very close resemblances with the Jagannath festivities. Further the season in which the Ratha-Yatra festival is observed is about the same time when the historic public processions welcomed Buddhist monks for their temporary, annual monsoon-season retirement.[50][note 2]

Another basis for this theory has been the observed mixing of people of Jagannath Hindu tradition contrary to the caste segregation theories popular with colonial era missionaries and Indologists. Since caste barriers never existed among devotees in Jagannath's temple, and Buddhism was believed to have been a religion that rejected caste system, colonial era Indologists and Christian missionaries such as Verrier Elwin suggested that Jagannath must have been a Buddhist deity and the devotees were a caste-rejecting Buddhist community.[3][54] According to Starza, this theory is refuted by the fact that other Indic traditions did not support caste distinctions, such as the Hindu Smarta tradition founded by Adi Shankara, and the traditional feeding of the Hindus together in the region regardless of class, caste or economic condition in the memory of Codaganga.[47] This reconciliation is also weak because Jagannath is venerated by all Hindu sects,[36] not just Vaishnavas or a regional group of Hindus, and Jagannath has a pan-Indian influence.[42][55] The Jagannath temple of Puri has been one of the major pilgrimage destination for Hindus across the Indian subcontinent since about 800 CE.[13]

Yet another circumstantial evidence is that Jagannath is sometimes identified with or substituted for Shakyamuni Buddha, as the ninth avatar of Vishnu by Hindus, when it could have been substituted for any other avatar.[50] Jagannath was worshipped in Puri by the Odias as a form of Shakyamuni Buddha from a long time. Jayadeva, in Gita Govinda also has described Shakyamuni Buddha as one among the Dasavatara. Indrabhuti, the ancient Buddhist king, describes Jagannath as a Buddhist deity in Jnanasidhi.[50] Further, as a Buddhist king, Indrabhuti worshipped Jagannath.[56] This is not unique to the coastal state of Odisha, but possibly also influenced Buddhism in Nepal and Tibet. In Nepal, Shakyamuni Buddha is also worshipped as Jagannath in Nepal.[57] This circumstantial evidence has been questioned because the reverent mention of Jagannath in the Indrabhuti text may merely be a coincidental homonym, may indeed refer to Shakyamuni Buddha, because the same name may refer to two different persons or things.[56]

Jain origins

Pandit Nilakantha Das suggested that Jagannath was a deity of Jain origin because of the appending of Nath to many Jain Tirthankars.[58] He felt Jagannath meant the 'World personified' in the Jain context and was derived from Jinanath. Evidence of the Jain terminology such as of Kaivalya, which means moksha or salvation, is found in the Jagannath tradition.[59] Similarly, the twenty two steps leading to the temple, called the Baisi Pahacha, have been proposed as symbolic reverence for the first 22 of the 24 Tirthankaras of Jainism.[3]

According to Annirudh Das, the original Jagannath deity was influenced by Jainism and is none other than the Jina of Kalinga taken to Magadha by Mahapadma Nanda.[60] The theory of Jain origins is supported by the Jain Hathigumpha inscription. It mentions the worship of a relic memorial in Khandagiri-Udayagiri, on the Kumara hill. This location is stated to be same as the Jagannath temple site. However, states Starza, a Jain text mentions the Jagannath shrine was restored by Jains, but the authenticity and date of this text is unclear.[61]

Another circumstantial evidence supporting the Jain origins proposal is the discovery of Jaina images inside as well as near the massive Puri temple complex, including those carved into the walls. However, this could also be a later addition, or suggestive of tolerance, mutual support or close relationship between the Jains and the Hindus.[61] According to Starza, the Jain influence on the Jagannath tradition is difficult to assess given the sketchy uncertain evidence, but nothing establishes that the Jagannath tradition has a Jain origin.[61]

Vaishnava origins

The Vaishnava origin theories rely on the iconographic details and the typical presence of the triad of deities, something that Buddhist, Jaina and tribal origins theories have difficulty in coherently explaining. The colors, state the scholars of the Vaishnava origin theory, link to black-colored Krishna and white-colored Balarama. They add that the goddess originally was Ekanamsa (Durga of Shaiva-Shakti tradition, sister of Krishna through his foster family). She was later renamed to Shubhadra (Lakshmi) per Vaishnava terminology for the divine feminine.[62]

The weakness of the Vaishnava origins theory is that it conflates two systems. While it is true that the Vaishnava Hindus in the eastern region of India worshipped the triad of Balarama, Ekanamsa and Krishna, it does not automatically prove that the Jagannath triad originated from the same. Some medieval texts, for example, present the Jagannath triad as Brahma (Subhadra), Shiva (Balarama) and Vishnu. The historic evidence and current practices suggest that the Jagannath tradition has a strong dedication to the Harihara (fusion Shiva-Vishnu) idea as well as tantric Shri Vidya practices, neither of which reconcile with the Vaishnava origins proposal.[62] Further, in many Jagannath temples of central and eastern regions of India, the Shiva icons such as the Linga-yoni are reverentially incorporated, a fact that is difficult to explain given the assumed competition between the Shaivism and Vaishnavism traditions of Hinduism.[62]

Tribal origins

The tribal origin theories rely on circumstantial evidence and inferences such as the Jagannath icon is non-anthropomorphic and non-zoomorphic.[21] The hereditary priests in the Jagannath tradition of Hinduism include non-Brahmin servitors, called Daitas, which may be an adopted grandfathered practice with tribal roots. The use of wood as a construction material for the Jagannath icons may also be a tribal practice that continued when Hindus adopted prior practices and merged them with their Vedic abstractions.[26] The practice of using wood for making murti is unusual, as Hindu texts on the design and construction of images recommend stone or metal.[13] The Daitas are Hindu, but believed to have been the ancient tribe of Sabaras (also spelled Soras). They continue to have special privileges such as being the first to view the new replacement images of Jagannath carved from wood approximately every 12 years. Further, this group is traditionally accepted to have the exclusive privilege of serving the principal meals and offerings to Jagannath and his associate deities.[13][22]

According to Verrier Elwin, a Christian missionary and colonial era historian, Jagannatha in a local legend was a tribal deity who was coopted by a Brahmin priest.[63] The original tribal deity, states Elwin, was Kittung which too is made from wood. According to the Polish Indologist Olgierd M. Starza, this is an interesting parallel but a flawed one because the Kittung deity is produced by burning a piece of wood and too different in its specifics to be the origin of Jagannath.[22] According to another proposal by Stella Kramrisch, log as a symbol of Anga pen deity is found in central Indian tribes and they have used it to represent features of the Hindu goddess Kali with it. However, states Starza, this theory is weak because the Anga pen features a bird or snake like attached head along with other details that make the tribal deity unlike the Jagannath.[22]

Some scholars such as Kulke and Tripathi have proposed tribal deities such as Stambhesveri or Kambhesvari to be a possible contributor to the Jagannath triad.[64] However, according to Starza, these are not really tribal deities, but Shaiva deities adopted by tribes in eastern states of India. Yet another proposal for tribal origins is through the medieval era cult of Lakshmi-Narasimha.[64] This hypothesis relies on the unusual flat head, curved mouth and large eyes of Jagannath, which may be an attempt to abstract an image of a lion's head ready to attack. While the tribal Narasimha theory is attractive states Starza, a weakness of this proposal is that the abstract Narasimha representation in the form does not appear similar to the images of Narasimha in nearby Konark and Kalinga temple artworks.[64]

In contemporary Odisha, there are many Dadhivaman temples with a wooden pillar god, and this may be same as Jagannath.[66]

Syncretic origins

According to Patnaik and others, Jagannath is a syncretic deity that combined aspects of major faiths like Saivism, Saktism, Vaishnavism, Jainism, and Buddhism.[9][10] Jagannath is worshipped as Purushottama form of Vishnu,[67] Gaudiya Vaishnavs have identified him strongly with Krishna.[68] In Gaudiya Vaishnav tradition, Balabhadra is the elder brother Balaram, Jagannath is the younger brother Krishna, and Subhadra is the youngest sister.[69]

Balabhadra considered the elder brother of Jagannath is sometimes identified with and worshipped as Shiva.[68] Subhadra now considered Jagannath's sister has also been considered as a deity who used to be Brahma[68] in some versions and worshipped as Adyasakti Durga in the form of Bhuvaneshwari in other versions.[70] Finally the fourth deity, Sudarsana Chakra symbolizes the wheel of Sun's Chariot, a syncretic absorption of the Saura (Sun god) tradition of Hinduism. The conglomerate of Jagannath, Balabhadra, Subhadra and Sudarshan Chakra worshipped together on a common platform are called the Chaturdha Murty or the "Four-fold Form".[71]

O.M. Starza states that the Jagannath Ratha Yatra may have evolved from the syncretism of procession rituals for Siva lingas, Vaishnava pillars, and tribal folk festivities.[72] The Saiva element in the tradition of Jagannath overlap with the rites and doctrines of Tantrism and Shaktism Dharma. According to the Saivas, Jagannath is Bhairava.[73] Shiva Purana mentions Jagannatha as one of the 108 names of Shiva.[74] The tantric literary texts identify Jagannath with Mahabhairav.[69] Another evidence that supports syncretism thesis is the fact that Jagannath sits on the abstract tantric symbols of Shri Yantra. Further, his Shri Chakra ("holy wheel") is worshipped in the Vijamantra 'Klim', which is also the Vijamantra of Kali or Shakti. The representation of Balaram as Sesanaga or Sankarsana bears testimony to the influence of Shaivism on the cult of Jagannath. The third deity, Devi Subhadra, who represents the Sakti element is still worshipped with the Bhuvaneshwari Mantra.[73]

The Tantric texts claim Jagannath to their own, to be Bhairava, and his companion to be same as Goddess Vimala is the Shakti. The offerings of Jagannath becomes Mahaprasad only after it is re-offered to Goddess Vimala. Similarly, different tantric features of Yantras have been engraved on the Ratna vedi, where Jagannath, Balabhadra and Devi Subhadra are set up. The Kalika Purana depicts Jagannath as a Tantric deity.[73] According to Avinash Patra, the rituals and special place accepted for non-Brahmin Daitas priests in Jagannath tradition, who co-exist and work together with Brahmin priests suggests that there was a synthesis of Tribal and Brahmanical traditions.[3]

According to the Jain version, the image of Jagannath (Black colour) represents sunya, Subhadra symbolizes the creative energy and Balabhadra (White colour) represents the phenomenal universe. All these images have evolved from the Nila Madhava, the ancient Kalinga Jina. "Sudarshana Chakra" is contended to be the Hindu name of the Dharma Chakra of Jaina symbol.

In the words of the historian Jadunath Sarkar:[75]

The diverse religions of Orissa in all ages have tended to gravitate towards and finally merged into the Jagannath worship, at least in theory.

Transformation from unitary icon to triad

The Madala Panji observes that Neela Madhav transformed into Jagannath and was worshipped alone as a unitary figure, not as the part of a triad. It is significant to note that the early epigraphic and literary sources refer only to a unitary deity Purushottama Jagannath.[76] The Sanskrit play "Anargharaghava" composed by Murari mentioned only Purushottama Jagannath and his consort Lakshmi with no references to Blabhadra and Subhadra.[76] The Dasgoba copper plated inscription dating to 1198 also mentions only Purushottama Jagannath in the context that the Puri temple had been originally built by Ganga king Anantavarman Chodaganga (1078–1147) for Vishnu and Lakshmi.[76] These sources are silent on the existence of Balabhadra and Subhadra. Such state of affairs has led to arguments that Purushottama was the original deity and Balabhadra and Subhadra were subsequently drawn in as additions to a unitary figure and formed a triad.

During the rule of Anangabhima III [1211–1239], Balabhadra and Subhadra find the earliest known mention in the Pataleshwara inscription of 1237 CE.[76] According to the German Indologist Kulke, Anangibhima III was the originator of the triad of Jagannath, Balabhadra, and Subhadra suggesting that Balabhadra was added after Laksmi's transformation into Subhadra. According to Bachu Siva Reddy, Triads are the forms of Mahavishnu and Subhadra is yogamaya and her husband is Jagannath’s friend Arjun.[77]

According to Mukerjee, Devi Subhadra could be subsequent addition upon the resurgence of Shaktism as the consort ("Not sister") of Jagannath.[78]

Theology

The theology and rituals associated with the Jagannatha tradition combine Vedic, Puranic and tantric themes. He is the Vedic Purushottama, the Puranic Narayana and the tantric Bhairava.[13] He is same as the metaphysical Brahman, the form of Lord Krishna that prevades as abstract kāla (time) in Vaishnava thought. He is abstraction which can be inferred and felt but not seen, just like time. Jagannath is chaitanya (consciousness), and his companion Subhadra represent Shakti (energy) while Balabhadra represents Jnana (knowledge).[13] According to Salabega, the Jagannath tradition assimilates the theologies found in Vaishnavism, Shaivism, Shaktism, Buddhism, Yoga and Tantra traditions.[79]

Love and compassion

The Jagannath theology overlaps with those of Krishna. For example, the 17th-century Oriya classic Rasa kallola by Dina Krushna opens with a praise to Jagannath, then recites the story of Krishna with an embedded theology urging the pursuit of knowledge, love and devotion to realize the divine in everything.[80] The 13th-century Jagannatha vijaya in Kannada language by Rudrabhatta is a mixed prose and poetry style text which is predominantly about Krishna. It includes a canto that explains that "Hari (Vishnu), Hara (Shiva) and Brahma" are aspects of the same supreme soul. Its theology, like the Oriya text, centers around supreme light being same as "love in the heart".[81] The 15th-century Bhakti scholar Shankaradeva of Assam became a devotee of Jagannatha in 1481, and wrote love and compassion inspired plays about Jagannatha-Krishna that influenced the region and remain popular in Assam and Manipur.[82]

Shunya Brahma

The medieval era Oriya scholars such as Ananta, Achyutananda and Chaitanya described the theology of Jagannath as the "personification of the Shunya, or the void", but not entirely in the form of Shunyata of Buddhism. They state Jagannath as "Shunya Brahma", or alternatively as "Nirguna Purusha" (or "abstract personified cosmos"). Vishnu avatars are descend from this Shunya Brahma into human form to keep dharma.[83][84]

Jagannath in Dharmic texts and traditions

Although Jagannath has been identified with other traditions in the past, He is now identified more with Vaishnav tradition.

Vaishnavite version

The Skanda Purana and Brahma Purana have attributed the creation of the Jagannathpuri during the reign of Indradyumna, a pious king and an ascetic who ruled from Ujjain. According to the second legend, associated with the Vaishnavas, when Lord Krishna ended the purpose of his Avatar with the illusionary death by Jara and his "mortal" remains were left to decay, some pious people saw the body, collected the bones and preserved them in a box. They remained in the box till it was brought to the attention of Indrdyumna by Lord Vishnu himself who directed him to create the image or a murti of Jagannath from a log and consecrate the bones of Krishna in its belly. Then King Indradyumna, appointed Vishwakarma, the architect of gods, a divine carpenter to carve the murti of the deity from a log which would eventually wash up on the shore at Puri. Indradyumna commissioned Vishwakarma (also said to be the divine god himself in disguise) who accepted the commission on the condition that he could complete the work undisturbed and in private.[85]

Everyone was anxious about the divine work, including the King Indradyumna. After a fortnight of waiting, the King who was anxious to see the deity, could not control his eagerness, and he visited the site where Vishwakarma was working. Soon enough Vishwakarma was very upset and he left the carving of the idol unfinished; the images were without hands and feet. The king was very perturbed by this development and appealed to Brahma to help him. Brahma promised the King that the images which were carved would be deified as carved and would become famous. Following this promise, Indradyumna organized a function to formally deify the images, and invited all gods to be present for the occasion. Brahma presided over the religions function as the chief priest and brought life (soul) to the image and fixed (opened) its eyes. This resulted in the images becoming famous and worshipped at Jagannath Puri in the well known Jagannath Temple as a Kshetra (pilgrimage centre). It is, however, believed that the original images are in a pond near the temple.[85]

Stories from the Ramayana and Mahabharata

According to Prabhat Nanda, the Valmiki Ramayana mentions Jagannath.[86] Some believe that the mythical place where King Janak performed a yajna and tilled land to obtain Sita is the same as the area in which the Gundicha temple is situated in Puri, according to Suryanarayan Das.[87] The Mahabharata, states Das, describes King Indradyumna's Ashvamedh Yajna and the advent of the four deities of the Jagannath cult.[87]

Sarala Dasa Mahabharata version

Sarala Dasa, the great Odia poet of the 15th century while praising Jagannath as the saviour of mankind considered him both as a form of Buddha as well as a manifestation of Krishna.[88]

Kanchi conquest

One of the most popular legends associated with Jagannath is that of Kanchi Avijana (or "Conquest of Kanchi"), also termed as "Kanchi-Kaveri". According to the legends,[89] the daughter of the King of Kanchi was betrothed to the Gajapati of Puri. When the Kanchi King witnessed the Gajapati King sweeping the area in front of where the chariots of Jagannath, Balabhadra and Subhadra were kept during Ratha yatra, he was aghast. Considering the act of sweeping unworthy of a King, the King of Kanchi declined the marriage proposal, refusing to marry his daughter to a 'Sweeper'. Gajapati Purushottam Deva, felt deeply insulted at this and attacked the Kingdom of Kanchin to avenge his honour. His attack was unsuccessful and his army defeated by the Kanchi Army.

Upon defeat, the Gajapati King Purushottam Deva returned and prayed to Jagannath, the God of land of Kalinga before planning a second campaign to Kanchi. Moved by his prayers, Jagannath and Balabhadra, left their temple in Puri and started an expedition to Kanchi on horseback. It is said that Jagannath rode on a white horse and Balabhadra on a black horse. The legend has such a powerful impact on the Oriya culture that the simple mention of white horse-black horse evokes the imagery of Kanchi conquest of the God in devotees minds.

On the road, Jagannath and Balabhadra grew thirsty and chanced upon a milkmaid Manika, who gave them butter-milk/yogurt to quench their thirst. Instead of paying her dues, Balabhadra gave her a ring telling her to claim her dues from King Purushottam. Later, Purushottam Deva himself passed by with his army. At Adipur near Chilika lake, the milkmaid Manika halted the King pleading for the unpaid cost of yogurt consumed by His army's two leading soldiers riding on black and white horses. She produced the gold ring as evidence. King Purusottam Deva identified the ring as that of Jagannath. Considering this a sign of divine support for his campaign, the king enthusiastically led the expedition.

In the war between the army of Kalinga inspired by the Divine support of Jagannath and of the army of Kanchi, Purushottam Deva led his army to victory. King Purusottam brought back the Princess Padmavati of Kanchi to Puri. To avenge his humiliation, he ordered his minister to get the princess married to a sweeper.[90] The minister waited for the annual Ratha Yatra when the King ceremonially sweeps Jagannath's chariot. He offered the princess in marriage to King Purusottam, calling the King a Royal sweeper of God. The King then married the Princess. The Gajapati King also brought back images of Uchista Ganesh (Bhanda Ganesh or Kamada Ganesh) and enshrined them in the Kanchi Ganesh shrine at the Jagannath Temple in Puri.

This myth has been recounted by Mohanty.[91] J.P. Das [92] notes that this story is mentioned in a Madala panji chronicle of the Jagannath Temple of Puri, in relation to Gajapati Purushottama. At any rate, the story was popular soon after Purushottama's reign, as a text of the first half of the 16th century mentions a Kanchi Avijana scene in the Jagannath temple. There is currently a prominent relief in the jaga mohan (prayer hall) of the Jagannath temple of Puri that depicts this scene.

In modern culture, Kanchi Vijaya is a major motif in Odissi dance.[93]

In Odia literature, the Kanchi conquest (Kanchi Kaveri) has significant bearing, in medieval literature romanticized as the epic Kanchi Kaveri by Purushottama Dasa in the 17th century and a work by the same name by Maguni Dasa.[94] The first Odia drama written by Ramashankar Ray, the father of Odia drama in 1880 is Kanchi Kaveri.[95]

The Kanchi Kingdom has been identified as the historical Vijayanagar Kingdom. As per historical records, Gajapati Purushottam Deva's expedition towards Virupaksha Raya II's Kanchi (Vijayanagar) Kingdom started during 1476 with Govinda Bhanjha as commander-in-chief. According to J. P. Das, the historicity of Kanchi conquest event is not certain.[96]

Early Vaishnav tradition

Vaishnavism is considered a more recent tradition in Odisha, being historically traceable to the early Middle Ages.[97]Ramanujacharya the great Vaishnav reformer visited Puri between 1107 and 1111 converting the King Ananatavarman Chodaganga from Shaivism to Vaishnavism.[98] At Puri he founded the Ramanuja Math for propagating Vaishnavism in Odisha. The Alarnatha Temple stands testimony to his stay in Odisha. Since the 12th century under the influence of Ramanujacharya, Jagannath was increasingly identified with Vishnu.[7] Under the rule of the Eastern Gangas, Vaishnavism became the predominant faith in Odisha.[99] Oriya Vaishnavism gradually centred on Jagannath as the principal deity. Sectarian differences were eliminated by assimilating deities of Shaivism, Shaktism and Buddhism in the Jagannath Pantheon.[97] The Ganga Kings respected all the ten avatars of Vishnu, considering Jagannath as the cause of all the Avatars. The Vaishnav saint Nimbaraka visited Puri, establishing the Radhavallav Matha in 1268.[98] The famous poet Jayadev was a follower of Nimbaraka and his focus on Radha and Krishna. Jayadev's composition Gita Govinda put a new emphasis on the concept of Radha and Krishna in East Indian Vaishnavism.[100] This idea soon became popular. Sarala Dasa in his Mahabharat thought of Jagannath as the universal being equating him with Buddha and Krishna. He considered Krishna as one of the Avatars of Jagannath[7]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu and Gaudiya Vaishnavism

Gaudiya Vaishnavism (also known as Chaitanya Vaishnavism[101] and Hare Krishna) is a Vaishnava religious movement founded by Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (1486–1534) in India in the 16th century. "Gaudiya" refers to the Gauda region (present day Bengal/Bangladesh) with Vaishnavism meaning "the worship of the monotheistic Deity or Supreme Personality of Godhead, often addressed as Krishna, Narayana or Vishnu".

The focus of Gaudiya Vaishnavism is the devotional worship (bhakti) of Krishna, as Svayam Bhagavan or the Original Supreme Personality of Godhead.[102]

Shree Jagannath has always been very close to the people of Bengal. In fact, upon visiting the main temple at Puri, almost 60% of the present pilgrims can be found to be from Bengal. Besides, Ratha Yatra is pompously celebrated in West Bengal, where Lord Jagannath is worshipped extensively in Bengal homes and temples. The day also marks the beginning of preparations for Bengal's biggest religious festival, the Durga Puja. This extensive popularity of Shree Jagannath among Bengalis can be related to Shree Chaitanya Mahaprabhu.

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu spent the last 20 years of his life in Puri dedicating it to the ecstatic worship of Jagannath whom he considered a form of Krishna.[103] Mahaprabhu propagated the Sankirtan movement which laid great emphasis on chanting God's name in Puri. He converted noted scholars like Sarvabhauma Bhattacharya to his philososphy. He left a great influence on the then king of Odisha, Prataprudra Deva, and the people of Odisha.[104] According to one version Chaitanya Mahaprabhu is said to have merged with the idol of Jagannath in Puri after his death[103]

Chaitanya Mahaprabhu changed the course of Oriya Vaishnav tradition emphasising Bhakti and strongly identifying Jagannath with Krishna.[68] His Gaudiya Vaishnav school of thought strongly discouraged Jagannath's identification with other cults and religions, thus re-establishing the original identity of Lord Jagannath as Supreme Personality of Godhead Shri Krishna.

The ISKCON Movement

Prior to the advent of ISKCON movement, Jagannath and his most important festival, the annual Ratha Yatra, were relatively unknown in the West.[105] Soon after its founding, ISKCON started founding temples in the West. A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada popularly called Shrila Prabhupada, the founder of ISKCON, selected Jagannath as one of the chosen forms of Krishna installing an deity of Jagannath in ISKCON temples around the world.[106] ISKCON has promoted Jagannath throughout the world. Annual Ratha Yatra festival is now celebrated by ISKCON in many cities in the West where they are popular attractions.[105] ISKCON devotees worship Jagannath and take part in the Ratha Yatra in memory of Chaitanya Mahaprabhu spending 18 years in Puri worshipping Jagannath and taking an active part in the Ratha Yatra[107]

Jagannath in Shaktism

Vimala (Bimala) is worshipped as the presiding goddess of the Purushottama (Puri) Shakti Pitha by Shaktas.Jagannath, is worshipped as the Bhairava, traditionally always a form of Shiva. Jagannath-Vishnu equated with Shiva, is interpreted to convey the oneness of God. Also, in this regard, Vimala is also considered as Annapurna, the consort of Shiva.[108] Conversely, Tantrics consider Jagannath as Shiva-Bhairava, rather than a form of Vishnu.[109] While Lakshmi is the traditional (orthodox tradition) consort of Jagannath, Vimala is the Tantric (heterodox) consort.[110] Vimala is also considered the guardian goddess of the temple complex, with Jagannath as the presiding god.[111]

Jagannath is considered the combination of 5 Gods Vishnu, Shiva, Surya, Ganesh and Durga by Shaktas. When Jagannath has his divine slumber (Sayana Yatra) he is believed to assume the aspect of Durga. According to the "Niladri Mahodaya"[112] Idol of Jagannath is placed on the Chakra Yantra, the idol of Balabhadra on the Shankha Yantra and the idol of Subhadra on the Padma Yantra.

Jagannath and Sikhism

In 1506 Guru Nanak the founder of Sikhism made a pilgrimage to Puri to visit to Jagannath.[114]

Later Sikh gurus like Guru Teg Bahadur also visited Jagannath Puri.[115] Maharaja Ranjit Singh the famous 19th-century Sikh ruler of Punjab held great respect in Jagannath, willed his most prized possession the Koh-i-Noor diamond to Jagannath in Puri, while on his deathbed in 1839.[116]

Jagannath and attacks from other religions

Jagannath and Islam

During the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal Empire era, Jagannath temples were one of the targets of the Muslim armies. Firuz Tughlaq, for example raided Odisha and desecrated the Jagannath temple according to his court historians.[117] Odisha was one of the last eastern regions to fall into the control of Sultanates and Mughal invasion, and they were among the earliest to declare independence and break away. According to Starza, the Jagannath images were the targets of the invaders, and a key religious symbol that the rulers would protect and hide away in forests from the aggressors.[118] However, the Muslims were not always destructive. For example, during the rule of Akbar, the Jagannath tradition flourished.[118] However, states Starza, "Muslim attacks on the Puri temple became serious after the death of Akbar, continued intermittently throughout the reign of Jahangir".[118]

The local Hindu rulers evacuated and hid the images of Jagannath and other deities many times between 1509 and 1734 CE, to "protect them from Muslim zeal" for destruction. During Aurangzeb's time, an image was seized, shown to the emperor and then destroyed in Bijapur, but it is unclear if that image was of Jagannath.[118] Muslim rulers did not destroy the Jagannath temple complex because it was a source of substantial treasury revenue through the collection of pilgrim tax collected from Hindus visiting it on their pilgrimage.[119]

Jagannath and Christianity

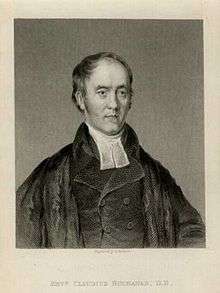

For Christian missionaries who arrived through the ports of eastern states of India such as Calcutta in the 18th- and 19th-centuries, Jagannath was the "core of idolatry" and the target of "an all-out attack".[122] Jagannath, called Juggernaut by the Christian missionary Claudius Buchanan, was through Buchanan's letters the initial introduction in America of Hinduism, which he termed as "Hindoo". According to Michael J. Altman, a professor of Religious Studies, Buchanan presented Hinduism to the American audience, through Juggernaut, as a "bloody, violent, superstitious and backward religious system" that needs to be eliminated and substituted with the Christian gospel.[120] He described Juggernaut with Biblical terminology for his audience, called him the Moloch, and his shrine as Golgatha – the place where Jesus Christ was crucified, but with the difference that the "Juggernaut tradition" was of endless meaningless bloodshed, fabricating allegations that children were sacrificed in the "valley of idolatrous blood shed to false gods".[120] In his letters, states Altman, Buchanan "constructed an image of Juggernaut as the diametric opposite of Christianity".[120]

In his book Christian Researches in Asia, published in 1811,[123] Buchanan built on this theme and added licentiousness to it. He called hymns in language he did not know nor could read as "obscene stanzas", art works on temple walls as "indecent emblems", and described "Juggernaut" and Hinduism to his American readers as the religion of disgusting Moloch and false gods. Buchanan writings formed the "first images of Indian religions" to the American evangelical audience in early 19th-century, was promoted by American magazines such as The Panoplist and his book on "Juggernaut" attracted enough reader demand that it was republished in numerous editions.[120] Buchanan's writings on "Juggernaut" influenced the American imagination of Indian religions for another 50 years, formed the initial impressions and served as a template for reports by other missionaries who followed Buchanan in India for most of the 19th century.[120] According to William Gribbin and other scholars, Buchanan's Juggernaut metaphor is a troublesome example of intercultural misunderstanding and constructed identity.[121][124][125]

Due to persistent attacks from non-Indic religions, even to this day, devotees of only Dharmic religions are allowed entry in the Jagannath puri temple.[126][127][128]

Influence

The English traveller William Burton visited the Jagannath temple. According to Avinash Patra, Burton made absurd observations in 1633 that are inconsistent with all historical and contemporary records, such as the image of Jagannatha being "a serpent, with seven heads".[129] Burton described it as "the mirror of all wickedness and idolatry" to the Europeans, an introduction of Hinduism as "monstrous paganism" to early travellers to the Indian subcontinent. Jean-Baptiste Tavernier never saw the Puri temple icon and its decorations, but described the jewelry worn by the idol from hearsay accounts.[129] François Bernier mentioned the Puri chariot festival, in his 1667 memoir, but did not describe the icon of Jagannath raising the question whether he was able to see it.[129]

According to Kanungo, states Goldie Osuri, the Jagannath tradition has been a means of legitimizing royalty.[130] Codaganga, a benevolent ruler of the Kalinga region (now Odisha and nearby regions), built the extant Puri temple. Kanungo states that this endeavor was an attempt by him to establish his agency, and he extrapolates this practice into late medieval and modern era developments.[130] According to him, Muslim rulers attempted to control it for the same motivation, thereafter the Marathas, then East India Company and then the British crown over the colonial era sough to legitimize its influence and hegemonic control in the region by appropriating control over the Jagannath temple and affiliating themselves with the deities.[130]

Jagannath became an influential figure and icon for power and politics during the 19th-century colonialism and Christian missionary activity, states Osuri.[130] The British government initially took over the control and management of major Jagannath temples, to collect fees and Pilgrim Tax from Hindu who arrived from all over the Indian subcontinent to visit.[131][note 3][note 4] In contrast, Christian missionaries strongly opposed the British government association with Jagannath temple because its connected the government with idolatry, or the "worship of false god". Between 1856 and 1863, the British government accepted the missionary demand and handed over the Jagannath temples to the Hindus.[130][133] According to Cassels and Mukherjee, the British rule documents suggest that the handing over was more motivated by the growing Hindu agitation against the Pilgrim Tax that they considered as discriminatory targeting based on religion, and rising corruption among the British officials and their Indian assistants, in the handling of collected tax.[134][135]

To colonial era Hindu nationalists in the late 19th-century and 20th-century, Jagannath became a unifying symbol which combined their religion, social and cultural heritage into a political cause of self-rule and freedom movement.[136]

Festivals

A large number of traditional festivals are observed by the devotees of Jagannath. Out of those numerous festivals, thirteen are important.[137]

- Niladri Mahodaya

- Snana Yatra

- Ratha Yatra or Shri Gundicha Yatra

- Shri Hari Sayan

- Utthapan Yatra

- Parswa Paribartan

- Dakhinayan Yatra

- Prarbana Yatra

- Pusyavishek

- Uttarayan

- Dola Yatra

- Damanak Chaturdasi[138]

- Chandan Yatra

Ratha Yatra is most significant of all festivals of Jagannath.

Ratha Yatra

The Jagannath triad are usually worshipped in the sanctum of the temple, but once during the month of Asadha (rainy season of Odisha, usually falling on the month of June or July), they are brought out onto the Bada Danda (Puri's main high street) and travel 3 km to the Shri Gundicha Temple, in huge chariots, allowing the public to have Darshan (i.e., holy view). This festival is known as Ratha Yatra, meaning the festival (yatra) of the chariots (ratha). The rathas are huge wheeled wooden structures, which are built anew every year and are pulled by the devotees. The chariot for Jagannath is approximately 14 metres (45 ft) high and 3.3 square metres (35 sq ft) and takes about 2 months to construct.[139] The artists and painters of Puri decorate the cars and paint flower petals etc. on the wheels, the wood-carved charioteer and horses, and the inverted lotuses on the wall behind the throne.[140] The huge chariot of Jagannath pulled during Ratha Yatra is the etymological origin of the English word juggernaut.[141] The Ratha Yatra is also termed as the Shri Gundicha Yatra.

The most significant ritual associated with the Ratha Yatra is the chhera pahara. During the festival, the Gajapati king wears the outfit of a sweeper and sweeps all around the deities and chariots in the Chera Pahara (Sweeping with water) ritual. The Gajapati king cleanses the road before the chariots with a gold-handled broom and sprinkles sandalwood water and powder with utmost devotion. As per the custom, although the Gajapati king has been considered the most exalted person in the Kalingan kingdom, still he renders the menial service to Jagannath. This ritual signified that under the lordship of Jagannath, there is no distinction between the powerful sovereign, the Gajapati king, and the most humble devotee.[142]

Chera pahara is held on two days, on the first day of the Ratha Yatra, when the deities are taken to the garden house at Mausi Maa Temple and again on the last day of the festival, when the deities are ceremoniously brought back to the Shri Mandir.

As per another ritual, when the deities are taken out from the Shri Mandir to the chariots in Pahandi vijay, disgruntled devotees hold a right to offer kicks, slaps and make derogatory remarks to the images, and Jagannath behaves like a commoner.

In the Ratha Yatra, the three deities are taken from the Jagannath Temple in the chariots to the Gundicha Temple, where they stay for seven days. Thereafter, the deities again ride the chariots back to Shri Mandir in bahuda yatra. On the way back, the three chariots stop at the Mausi Maa Temple and the deities are offered poda pitha, a kind of baked cake which are generally consumed by the poor sections only.

The observance of the Ratha Yatra of Jagannath dates back to the period of the Puranas. Vivid descriptions of this festival are found in Brahma Purana, Padma Purana and Skanda Purana. Kapila Samhita also refers to Ratha Yatra. During the Moghul period, King Ramsingh of Jaipur, Rajasthan, has also been described as organizing the Ratha Yatra in the 18th century. In Odisha, kings of Mayurbhanj and Parlakhemundi also organized the Ratha Yatra, though the most grand festival in terms of scale and popularity takes place at Puri.

In fact, Starza[143] notes that the ruling Ganga dynasty instituted the Ratha Yatra at the completion of the great temple around 1150. This festival was one of those Hindu festivals that was reported to the Western world very early. Friar Odoric of Pordenone visited India in 1316–1318, some 20 years after Marco Polo had dictated the account of his travels while in a Genovese prison.[144] In his own account of 1321, Odoric reported how the people put the "idols" on chariots, and the king and queen and all the people drew them from the "church" with song and music.[145] [146]

Jagannath temples

Besides the only temple described below, there are many temples in India, three more in Bangladesh and one in Nepal.

.jpg)

The Temple of Jagannath at Puri is one of the major Hindu temples in India. The temple is built in the Kalinga style of architecture, with the Pancharatha (Five chariots) type consisting of two anurathas, two konakas and one ratha. Jagannath temple is a pancharatha with well-developed pagas. 'Gajasimhas' (elephant lions) carved in recesses of the pagas, the 'Jhampasimhas' (Jumping lions) are also placed properly. The perfect pancharatha temple developed into a Nagara-rekha temple with unique Oriya style of subdivisions like the Pada, Kumbha, Pata, Kani and Vasanta. The Vimana or the apsidal structure consists of several sections superimposed one over other, tapering to the top where the Amalakashila and Kalasa are placed.[147]

Temple of Jagannath at Puri has four distinct sectional structures, namely -

- Deula or Vimana (Sanctum sanctorum) where the triad deities are lodged on the ratnavedi (Throne of Pearls);

- Mukhashala (Frontal porch);

- Nata mandir/Natamandapa, which is also known as the Jaga mohan, (Audience Hall/Dancing Hall), and

- Bhoga Mandapa (Offerings Hall).[148]

The temple is built on an elevated platform, as compared to Lingaraja temple and other temples belonging to this type. This is the first temple in the history of Kalingaan temple architecture where all the chambers like Jagamohana, Bhogamandapa and Natyamandapa were built along with the main temple. There are miniature shrines on the three outer sides of the main temple.

The Deula consists of a tall shikhara (dome) housing the sanctum sanctorum (garbhagriha). A pillar made of fossilized wood is used for placing lamps as offering. The Lion Gate (Singhadwara) is the main gate to the temple, guarded by two guardian deities Jaya and Vijaya. A 16-sided, 11-metre-high (36 ft) granite monolithic columnar pillar known as the Aruna Stambha (Solar Pillar) bearing Aruna, the charioteer of Surya, faces the Lion Gate. This column was brought here from the Sun temple of Konark.

The temple's historical records Madala panji maintains that the temple was originally built by King Yayati of the Somavamsi dynasty on the site of the present shrine. However, the historians question the veracity and historicity of the Madala Panji. As per historians, the Deula and the Mukhashala were built in the 12th century by Ganga King Anangabheemadeva, the grandson of Anantavarman Chodaganga and the Natamandapa and Bhogamandapa were constructed subsequently during the reign of Gajapati Purushottama Deva (1462–1491) and Prataprudra Deva (1495–1532) respectively. According to Madala Panji, the outer prakara was built by Gajapati Kapilendradeva (1435–1497). The inner prakara called the Kurma bedha (Tortoise encompassment) was built by Purushottama Deva.

See also

Notes

- The shape of Balabhadra's head, also called Balarama or Baladeva, varies in some temples between somewhat flat and semi-circular.[27]

- The same ancient monastic practice of 3-4 months temporary retirement of all monks and nuns, to take shelter at one place during the heavy rainfalls of monsoons, is found in the Hindu and Jain monastic traditions.[52][53]

- Claudius Buchanan mentions the Pilgrim Tax was collected from Hindus after they had walked very long distances, for many weeks, to visit the Puri temple. Anyone refusing to pay would be denied entry to the city.[132]

- The pilgrim tax was not a British invention, and was a religious tax on Hindus introduced by the Muslim rulers during the Mughal era.[119]

References

- Jayanti Rath. "Jagannath- The Epitome of Supreme Lord Vishnu" (PDF).

- https://puri.nic.in/tourist-place/shreejagannath/

- Avinash Patra (2011). Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath. Oxford University Press. pp. 8–10, 17–18.

- "Synthetic Character of Jagannath Culture", Pp. 1–4 Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Avinash Patra (2011). Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath. Oxford University Press. pp. 5–16.

- Wilkins, William Joseph (1900). Hindu Mythology, Vedic and Puranic. London: Elibron Classics. ISBN 978-81-7120-226-3.

- Mukherjee, Prabhat The history of medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. P.155

- Pradhan, Atul Chandra (June 2004). "Evolution of Jagannath Cult" (PDF). Orissa Review: 74–77. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- Patnaik, Bibhuti (3 July 2011). "My friend, philosopher and guide". The Telegraph. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Misra, Narayan (2005). Annals and Antiquities of the Temple of Jagannātha. Jagannathism: Sarup& Sons. p. 97. ISBN 9788176257473.

- Tripathy, B; Singh P.K. (June 2012). "Jagannath Cult in North-east India" (PDF). Orissa Review: 24–27. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- See: Chakravarti 1994, p 140

- Bijoy M Misra (2007). Edwin Francis Bryant (ed.). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 139–141. ISBN 978-0-19-803400-1.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduikm: N-Z. Rosen Publishing. p. 567. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Das, Basanta Kumar (2009). "Lord Jagannath Symbol of National Integration" (PDF). Orissa Review. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

The term Jagannath etymologically means the Lord of the Universe

- Eschmann, Anncharlott (1978). The Cult of Jagannath and the regional tradition of Orissa. University of California, California, San Francisco, USA: Manohar. p. 537.

- Mohanty, Surendra. Lord Jagannatha: the microcosm of Indian spiritual culture, p. 93. Orissa Sahitya Academy (1982)

- "::: LordJagannath.Co.in ::: Lord Jagannath (Names)". lordjagannath.co.in. 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

Different names of Shree Jagannath

- "The Sampradaya Sun - Independent Vaisnava News - Feature Stories - March 2008".

- "64 Names of Lord Jagannath Around Odisha | PURIWAVES". puriwaves.nirmalya.in. Retrieved 11 December 2012.

Sri Jagannath is being worshipped throughout Orissa over thirty districts in 64 names.

- Joshi, Dina Krishna (June–July 2007). "Lord Jagannath: the tribal deity" (PDF). Orissa Review: 80–84. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 65–67 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Wendy Doniger; Merriam-Webster, In (1999). Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions. Merriam-Webster. p. 547. ISBN 978-0-87779-044-0.

- Santilata Dei (1988). Vaiṣṇavism in Orissa. Punthi. pp. 58–59. ISBN 978-81-85094-14-4.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Chowdhury, Janmejay. "Iconography of Jagannath" (PDF). Srimandir: 21–23. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Thomas E. Donaldson (2002). Tantra and Śākta Art of Orissa. DK Printworld. pp. 779–780. ISBN 978-81-246-0198-3.

- Pattanaik, Shibasundar (July 2002). "Sudarsan of Lord Jagannath" (PDF). Orissa Review: 58–60. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- "The origin of Patita Pavana" (PDF). Sri Krishna Kathamrita. Sri Gopaljiu. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Das, Madhavananda (8 June 2004). "The Story of Gopal Jiu". Vaishnav News. Archived from the original on 13 September 2010. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Vaishnava. Cz. "Jagannatha Puri". Bhakti Vedanta Memorial Library. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Peter J. Claus; Sarah Diamond; Margaret Ann Mills (2003). South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. p. 515. ISBN 978-0-415-93919-5.

- Asiatic Journal. Parbury, Allen, and Company. 1841. pp. 233–. Retrieved 15 December 2012.

- Mishra, Kabi (3 July 2011). "He is the infinite Brahman". The Telegraph, Kolkata. Retrieved 1 December 2012.

- Ray, Dipti (2007). Prataparudradeva, the Last Great Suryavamsi King of Orissa (A.D. 1497 to A.D. 1540). Northern Book Centre. p. 151. ISBN 9788172111953. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- Asiatic Society of Bengal (1825). Asiatic researches or transactions of the Society instituted in Bengal, for inquiring into the history and antiquities, the arts, sciences, and literature, of Asia. p. 319.

- Srinivasan (2011). Hinduism For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-118-11077-5.

- Dash, Durgamadhab (June 2007). "Place of Chakratirtha in the cult of Lord Jagannath" (PDF). Orissa Review. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Mohanty, Tarakanta (July 2005). "Lord Jagannath in the form of Lord Raghunath and Lord Jadunath" (PDF). Orissa Review: 109–110. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Avinash Patra (2011). Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath. Oxford University Press. pp. 4–18.

- Jitāmitra Prasāda Siṃhadeba (2001). Tāntric Art of Orissa. Gyan Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-81-7835-041-7.

- Jagannath Mohanty (2009). Encyclopaedia of Education, Culture and Children's Literature: v. 3. Indian culture and education. Deep & Deep Publications. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-8450-150-6.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. Brill. p. 64. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- James G. Lochtefeld (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: Volume Two. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 665. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

- Index of 16 Purans. Markandeya. 2009. pp. 18, 19.

- Ralph TH Griffith. Rig Veda. verse 10.155.3: Wikisource.CS1 maint: location (link); Quote: अदो यद्दारु प्लवते सिन्धोः पारे अपूरुषम् । तदा रभस्व दुर्हणो तेन गच्छ परस्तरम् ॥३॥

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 59–60 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 58–59 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Ananda Abeysekara (2002). Colors of the Robe: Religion, Identity, and Difference. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 148–149. ISBN 978-1-57003-467-1.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 54–56 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Faxian: Chinese Buddhist Monk, Encyclopedia Britannica

- Paul Gwynne (2011). World Religions in Practice: A Comparative Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. p. 5. ISBN 978-1-4443-6005-9.

- Michael Carrithers; Caroline Humphrey (1991). The Assembly of Listeners: Jains in Society. Cambridge University Press. pp. 50–51. ISBN 978-0-521-36505-5.

- Brad Olsen (2004). Sacred Places Around the World: 108 Destinations. CCC Publishing. p. 91. ISBN 978-1-888729-10-8.

- K. K. Kusuman (1990). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. p. 162. ISBN 978-81-7099-214-1.

- Avinash Patra (2011). Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–7.

- Kar. Dr. Karunakar. Ascharja Charjachaya. Orissa Sahitya Akademy (1969)

- Mohanty, Jagannath (2009). Indian Culture and Education. Deep& Deep. p. 5. ISBN 978-81-8450-150-6.

- Barik, P M (July 2005). "Jainism and Buddhism in Jagannath culture" (PDF). Orissa Review: 36. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Das, Aniruddha. Jagannath and Nepal. pp. 9–10.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 62–63 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 63–64 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Elwin, Verrier (1955). The Religion of an Indian Tribe. Oxford University Press (Reprint). p. 597.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 67–70 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Gavin D. Flood (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-521-43878-0.

- Mohanty, P.C. (June 2012). "Jagannath temples of Ganjam" (PDF). Odisha Review: 113–118. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- "History od deities". Jagannath temple, Puri administration. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Bryant, Edwin F (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0195148916.

- Das, Suryanarayan (2010). Lord Jagannath. Sanbun. p. 89. ISBN 978-93-80213-22-4.

- "History of deities". Jagannath temple, Puri administration. Archived from the original on 2 April 2013. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Behera, Prajna Paramita (June 2004). "The Pillars of Homage to Lord Jagannatha" (PDF). Orissa Review: 65. Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- Starza 1993, p. 70, 97, 105.

- Behuria, Rabindra Kumar (June 2012). "The Cult of Jagannath" (PDF). Orissa Review. pp. 42–43. Retrieved 28 April 2013.

- Purana, Shiva. "Shiva Shahasranama". harekrsna.de. Retrieved 27 March 2019.

- Siṃhadeba, Jitāmitra Prasāda (2001). Tāntric Art of Orissa. Evolution of tantra in Orissa: Kalpaz Publications. p. 145. ISBN 978-81-7835-041-7.

- Tripathy, Manorama (June 2012). "A Reassessment of the origin of the Jagannath cult of Puri" (PDF). Orissa Review: 30. Retrieved 4 December 2012.

- Kulke, Herman (1978). The Cult of Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa. Manohar. p. 26.

- Mukherjee, Prabhat (1981). The History of Medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa. Asian Educational Services. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9788120602298.

- Sālabega (1998). White Whispers: Selected Poems of Salabega. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-81-260-0483-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 341. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 347. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. pp. 373–374. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Roshen Dalal (2010). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin Books. p. 388. ISBN 978-0-14-341421-6.

- Tandra Patnaik (2005). Śūnya Puruṣa: Bauddha Vaiṣṇavism of Orissa. DK Printworld. pp. 111–119. ISBN 978-81-246-0345-1.

- Deshpande, Aruna (2005). India: A Divine Destination. Crest Publishing House. p. 203. ISBN 978-81-242-0556-3.

- Nanda, Prabhat Kumar (June–July 2007). Shree Jagannath and Shree Ram. Orissa Review. pp. 110–111. ISBN 9789380213224. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Das, Suryanarayan (2010). Lord Jagannath. Sanbun. p. 13. ISBN 978-93-80213-22-4.

- Das, Suryanarayan (2010). Lord Jagannath. Sanbun. p. 26. ISBN 978-93-80213-22-4.

- Das, Suryanarayan (2010). Lord Jagannath. Sanbun. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-93-80213-22-4.

- Purushottam Dev and Padmavati. Amar Chitra Katha.

- Mohanty 1980, p. 7.

- Das 1982, p. 120.

- "Guruji's Compositions:Dance and Drama". of Kelucharan Mohapatra. Srjan. Archived from the original on 29 October 2012. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Mukherjee, Sujit (1999). Dictionary of Indian Literature One: Beginnings - 1850. Orient Longman. p. 163. ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9.

- Datta, Amaresh (1988). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: devraj to jyoti. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1091. ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0.

- Das 1982, p. 120-121.

- Panigrahi, K.C. (1995). History of Orissa. Kitab Mahal. p. 320.

- Kusuman, K.K. (1990). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. p. 166. ISBN 9788170992141.

- Ray, Dipti (2007). Prataparudradeva, the Last Great Suryavamsi King of Orissa. Religious conditions: Northern Book Centre. p. 149. ISBN 9788172111953.

- Datta, Amaresh (1988). Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature: devraj to jyoti. Sahitya Akademi. p. 1421. ISBN 9788126011940.

- Hindu Encounter with Modernity, by Shukavak N. Dasa Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine "

- "All of the above-mentioned incarnations are either plenary portions or portions of the plenary portions of the Lord, but Lord Shri Krishna is the original Personality of Godhead." Bhagavat Purana 1:3:28

- Kulke, Herman (2004). A History of India, 4th edition. Routledge. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-415-32920-0.

- Bryant, Edwin Francis (2004). The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Columbia University Press. pp. 68–71. ISBN 9780231508438.

- Melton, Gordon (2007). The Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena. Jagannath: Visible Ink Press. ISBN 9781578592593.

- Waghorne, J.P. (2004). Diaspora of the Gods:Modern Hindu Temples in an Urban Middle-Class World. Oxford University Press. p. 32. ISBN 9780198035572.

- Bromley, David (1989). Krishna Consciousness in West. Bucknell University Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780838751442.

- Tripathy, Shrinibas (September 2009). "Goddess Bimala at Puri" (PDF). Orissa Review: 66–69. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "THE TEMPLE OF JAGANNATHA" (PDF). Official site of Jagannath temple. Shree Jagannath Temple Administration, Puri. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 May 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- Starza 1993, p. 20.

- Mahapatra, Ratnakar (September–October 2005). "Vimala Temple at the Jagannath Temple Complex, Puri" (PDF). Orissa Review: 9–14. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- Simhadeba, J.P. (2001). Tantric Art of Orissa. Gyan Books. p. 133. ISBN 9788178350417.

- Isabel Burton (2012). Arabia, Egypt, India: A Narrative of Travel. Cambridge University Press. p. 168. ISBN 978-1-108-04642-8.

- K.K. Kusuman (1990). A Panorama of Indian Culture: Professor A. Sreedhara Menon Felicitation Volume. Mittal Publications. p. 167. ISBN 9788170992141.

- S.S. Johar, University of Wisconsin--Madison Center for South Asian Studies (1975). Guru Tegh Bahadur. Abhinav Publications. p. 149. ISBN 9788170170303.

- The Real Ranjit Singh; by Fakir Syed Waheeduddin, published by Punjabi University, ISBN 81-7380-778-7, 1 Jan 2001, 2nd ed.

- Satish Chandra (2004). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals-Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526). Mushilal Manoharlal. pp. 216–217. ISBN 978-81-241-1064-5.

- O. M. Starza (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. pp. 146–147. ISBN 978-90-04-09673-8.

- Nancy Gardner Cassels (1988). Religion and Pilgrim Tax Under the Company Raj. Riverdale. pp. 17–22. ISBN 978-0-913215-26-5.

- Michael J. Altman (2017). Heathen, Hindoo, Hindu: American Representations of India, 1721-1893. Oxford University Press. pp. 30–33. ISBN 978-0-19-065492-4.

- Gribbin, William (1973). "The juggernaut metaphor in American rhetoric". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 59 (3): 297–303. doi:10.1080/00335637309383178.

- Hermann Kulke; Burkhard Schnepel (2001). Jagannath Revisited: Studying Society, Religion, and the State in Orissa. Manohar. pp. 159–160. ISBN 978-81-7304-386-4.

- Buchanan, Claudius (1811). Researches in Asia with Notices of the Translation of the Scriptures into the Oriental Languages.

- S. Behera (2007), Essentialising the Jagannath cult: a discourse on self and other, Journal of Comparative Literature and Aesthetics, Volume 30, Number 1-2, pages 51-53

- Nancy Gardner Cassels (1972), The Compact and the Pilgrim Tax: The Genesis of East India Company Social Policy, Canadian Journal of History, Volume 7, Number 1, pages 45-48

- https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/sc-urges-jagannath-temple-to-allow-entry-of-non-hindus/articleshow/64877985.cms

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zGKoxGyzJhk

- http://magazines.odisha.gov.in/Orissareview/2012/June/engpdf/110-115.pdf

- Patra, Avinash (2011). "Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath". University of Oxford Journal: 5–9. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Goldie Osuri (2013). Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (anti) Conversion. Routledge. pp. 55–56. ISBN 978-0-415-66557-5.

- Ingham, Kenneth (1952). "The English Evangelicals and the Pilgrim Tax in India, 1800–1862". The Journal of Ecclesiastical History. 3 (2): 191–200. doi:10.1017/s0022046900028426.

- Claudius Buchanan (1812). Christian Researches in Asia, Ninth edition. T. Cadell & W. Davies. pp. 20–21.

- James Peggs (1830). Pilgrim Tax in India: The Great Temple in Orissa, Second edition. London: Seely, Fleet-Street.

- Nancy Gardner Cassels; Sri Prabhat Mukherjee (2000). Pilgrim Tax and Temple Scandals: A Critical Study of the Important Jagannath Temple Records During British Rule. Orchid. pp. 96–108. ISBN 978-974-8304-72-4.

- N. Chatterjee (2011). The Making of Indian Secularism: Empire, Law and Christianity, 1830-1960. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 58–67. ISBN 978-0-230-29808-8.

- Goldie Osuri (2013). Religious Freedom in India: Sovereignty and (anti) Conversion. Routledge. pp. 56–57. ISBN 978-0-415-66557-5.

- "Festivals of Lord Sri Jagannath". nilachakra.org. 2010. Archived from the original on 22 October 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

By large 13 festivals are celebrated at Lord Jagannath Temple

- "Damanaka Chaturdasi - Jagannath Temple". jagannathtemplepuri.com. Retrieved 21 December 2012.

This falls in the month of Chaitra. On this day, the deities pay a visit to the garden of the celebrated Jagannath Vallabha Matha where they pick-up the tender leaves of the Dayanaa unnoticed by anybody.

- Starza 1993, p. 16.

- Das 1982, p. 40.

- "Juggernaut, definition and meaning". Merriam Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Karan, Jajati (4 July 2008). "Lord Jagannath yatra to begin soon". IBN Live. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Starza 1993, p. 133.

- Mitter 1977, p. 10.

- Starza 1993, p. 129.

- Das 1982, p. 48.

- "Architecture of Jagannath temple". Jagannath temple, Puri. Archived from the original on 20 November 2012. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- "Jagannath Temple, India - 7 wonders". 7wonders.org. 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

The temple is divided into four chambers: Bhogmandir, Natamandir, Jagamohana and Deul

Bibliography

- Das, Bikram: Domain of Jagannath - A Historical Study, BR Publishing Corporation.

- Das, J. P. (1982), Puri Paintings: the Chitrakara and his Work, New Delhi: Arnold Heinemann

- Das, M.N. (ed.): Sidelights on History and Culture of Orissa, Cuttack, 1977.

- Das, Suryanarayan: Jagannath Through the Ages, Sanbun Publishers, New Delhi. (2010)

- Eschmann, A., H. Kulke and G.C. Tripathi (Ed.): The Cult of Jagannath and the Regional Tradition of Orissa, 1978, Manohar, Delhi.

- Hunter, W.W. Orissa: The Vicissitudes of an Indian Province under Native and British Rule, Vol. I, Chapter-III, 1872.

- Kulke, Hermann in The Anthropology of Values, Berger Peter (ed.): Yayati Kesari revisted, Dorling Kindrsley Pvt. Ltd., (2010).

- Mohanty, A. B. (Ed.): Madala Panji, Utkal University reprinted, Bhubaneswar, 2001.

- Mahapatra, G.N.: Jagannath in History and Religious Tradition, Calcutta, 1982.

- Mahapatra, K.N.: Antiquity of Jagannath Puri as a place of pilgrimage, OHRJ, Vol. III, No.1, April, 1954, p. 17.

- Mahapatra, R.P.: Jaina Monuments of Orissa, New Delhi, 1984.

- Mishra, K.C.: The Cult of Jagannath, Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyaya, Calcutta, 1971.

- Mishra, K.C.: The Cult of Jagannath, Calcutta, 1971.

- Mishra, Narayan and Durga Nandan: Annals and antiquities of the temple of Jagannath, Sarup & Sons, New Delhi, 2005.

- Mitter, P. (1977), Much Maligned Monsters: A History of European Reactions to Indian Art, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 9780226532394

- Mohanty, B.C. and Buhler, Alfred: Patachitras of Orissa. (Study of Contemporary Textile Crafts of India). Ahmedabad, India: Calico Museum of Textiles, 1980.

- Mohapatra, Bishnu, N.: Ways of 'Belonging': The Kanchi Kaveri Legend and the Construction of Oriya Identity, Studies in History, 12, 2, n.s., pp. 204–221, Sage Publications, New Delhi (1996).

- Mukherji, Prabhat: The History of Medieval Vaishnavism in Orissa, Calcutta, 1940.

- Nayak, Ashutosh: Sri Jagannath Parbaparbani Sebapuja (Oriya), Cuttack, 1999.

- Padhi, B.M.: Daru Devata (Oriya), Cuttack, 1964.

- Panda, L.K.: Saivism in Orissa, New Delhi, 1985.

- Patnaik, H.S.: Jagannath, His Temple, Cult and Festivals, Aryan Books International, New Delhi, 1994, ISBN 81-7305-051-1.

- Patnaik, N.: Sacred Geography of Puri : Structure and Organisation and Cultural Role of a Pilgrim Centre, Year: 2006, ISBN 81-7835-477-2

- Rajguru, S.N.: Inscriptions of Jagannath Temple and Origin of Purushottam Jagannath, Vol.-I.

- Ray, B. C., Aioswarjya Kumar Das (Ed.): Tribals of Orissa: The changing Socio-Economic Profile, Centre for Advanced Studies in History and Culture, Bhubaneswar. (2010)

- Ray, B.L.: Studies in Jagannatha Cult, Classical Publishing Company, New Delhi, 1993.

- Ray, Dipti: Prataparudradeva, the last great Suryavamsi King of Orissa (1497)

- Sahu, N.K.: Buddhism in Orissa, Utkal University, 1958.

- Siṃhadeba, Jitāmitra Prasāda: Tāntric art of Orissa

- Singh, N.K.: Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Volume 1.

- Sircar, D.C.: Indian Epigraphy, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 1965.

- Starza-Majewski, Olgierd M. L: The Jagannatha temple at Puri and its Deities, Amsterdam, 1983.

- Starza, O. M. (1993). The Jagannatha Temple at Puri: Its Architecture, Art, and Cult. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-9004096738.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Upadhyay, Arun Kumar: Vedic View of Jagannath: Series of Centre of Excellence in Traditional Shastras :10, Rashtriya Sanskrita Vidyapeetha, Tirupati-517507, AP. [2006]

- Origin & Antiquity of the Cult of Lord Jagannath, Avinash Patra, Oxford University Press, England, 2011

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jagannath. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Jagannath. |