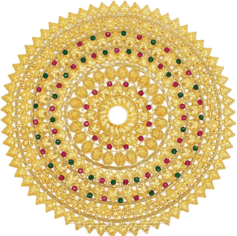

Sudarshana Chakra

The Sudarshana Chakra/Sudharshana Chakra (सुदर्शन चक्र) is a very powerful spinning, disk-like weapon, literally meaning "disk of auspicious vision," having 108 serrated edges used by the Hindu god Vishnu. The Sudarshana Chakra is generally portrayed on the right rear hand of the four hands of Vishnu, who also holds a shankha (conch shell), a Gada (mace) and a padma (lotus).[1] While in the Rigveda the Chakra was Vishnu's symbol as the wheel of time, by the late period Sudarshana Chakra emerged as an ayudhapurusha (anthropomorphic form), as a fierce form of Vishnu, used for the destruction of an enemy. In Tamil, the Sudarshana Chakra is also known as Chakkrath Azhwar (translated as Ring/Circlet of God).

| Sudarshana Chakra | |

|---|---|

Vishnu with Sudarshana Chakra in his right rear hand | |

| Devanagari | सुदर्शन चक्र |

| Affiliation | Weapon of Vishnu and his Avatar Krishna |

| Texts | Vishnu Purana |

Etymology

The word Sudarshana is derived from two Sanskrit words – Su(सु) meaning "good/auspicious" and Darshana (दर्शन) meaning "vision". In the Monier-Williams dictionary the word Chakra is derived from the root क्रम् (kram) or ऋत् (rt) or क्रि (kri) and refers among many meanings, to the wheel of a carriage, wheel of the sun's chariot or metaphorically to the wheel of time.[2][3]

The anthropomorphic form of Sudarshana can be traced from discoid weapons of ancient India to his esoteric multi-armed images in the medieval period in which the Chakra served the supreme deity (Vishnu) as his faithful attendants.[4] While the two-armed Chakra-Purusha was humanistic, the medieval multi-armed Sudarshana was speculatively regarded as an impersonal manifestation of destructive forces in the universe; that, in its final aspect, combined the flaming weapon and the wheel of time which destroys the universe.[4][5]

Legends

- The Chakra finds mention in the Rigveda as a symbol of Vishnu, and as the wheel of time,[6] and in the Itihasas and Puranas. In the Mahabharatha, Krishna, identified with Vishnu, uses it as a weapon. For example, he beheads Shishupala with the Sudarshana Chakra at the Rajasuya yagna of Emperor Yudhishthira.

- According to the Valmiki Ramayana, Purushottama (Vishnu) killed a Danava named Hayagriva on top of mountain named Chakravana constructed by Vishvakarma and took away a Chakra i.e. the Sudarshana Chakra from him.

- In the Puranas, the Sudarshana Chakra was made by the architect of gods, Vishvakarma. Vishvakarma's daughter Sanjana was married to Surya. Due to the Sun's blazing light and heat, she could not go near the Sun. She complained to her father about this. Vishvakarma made the sun shine less so that his daughter could hug the Sun. The leftover stardust was collected by Vishvakarma and made into three divine objects, (1) the aerial vehicle Pushpaka Vimana, (2) Trishula of Shiva, (3) Sudarshana Chakra of Vishnu. The Chakra is described to have 10 million spikes in two rows moving in opposite directions to give it a serrated edge.

- Sudarshana Chakra was used to cut the corpse of Sati, the consort of Shiva into 51 pieces after she gave up her life by throwing herself in a yagna (fire sacrifice) of her father Daksha. Shiva, in grief, carried around her lifeless body and was inconsolable. The 51 parts of the goddess' body were then tossed about in different parts of the Indian subcontinent and became "Shakti Peethas".

- In the Mahabharata, Jayadratha is responsible for the death of Arjuna's son, Arjuna vowing to avenge him by killing Jayadratha the very next day before sunset. However Drona creates a combination of 3 layers of troops, which act as a protective shield around Jayadratha. So Krishna creates an artificial sunset using his Sudarshana Chakra. Seeing this Jayadratha comes out of the protection to celebrate Arjuna's defeat. At that very moment, Krishna withdraws his Chakra to reveal the sun. Krishna then commands Arjuna to kill him and Arjuna follows his orders, beheading Jayadratha.

- Also, in the Mahabharata, Sisupala was beheaded by Krishna after he invoked the Chakra.

- There are several puranic stories associated with the Sudarshana Chakra, such as that of Lord Vishnu granting King Ambarisha the boon of Sudarshana Chakra in form of prosperity, peace, and security to his kingdom.

- Sudarshana Chakra was also used to behead Rahu and cut the celestial Mandra Parvat during the Samudra Manthan

Historical evidence

The chakra is found in the coins of many tribes with the word gana and the name of the tribe inscribed on them.[8] Early historical evidence of the Sudarshana-Chakra is found in a rare tribal Vrishni silver coin with the legend Vṛishṇi-rājaṅṅya-gaṇasya-trātasya which P.L.Gupta thought was possibly jointly issued by the gana (tribal confederation) after the Vrishnis formed a confederation with the Rajanya tribe. However, there is no conclusive proof so far. Discovered by Cunningham, and currently placed in the British Museum, the silver coin is witness to the political existence of the Vrishnis.[9][10] It is dated to around 1st century BCE.[8] Vrishni copper coins dated to later time were found in Punjab. Another example of coins inscribed with the chakra are the Taxila coins of the 2nd century BCE with a sixteen-spoked wheel.[8]

A coin dated to 180 BCE, with an image of Vasudeva-Krishna, was found in the Greco-Bactrian city of Ai-Khanoum in the Kunduz area of Afghanistan, minted by Agathocles of Bactria.[11][12] In Nepal, Jaya Cakravartindra Malla of Kathmandu issued a coin with the chakra.[13]

Among the only two types of Chakra-vikrama coins known so far, there is one gold coin in which Vishnu is depicted as the Chakra-purusha. Though Chandragupta II issued coins with the epithet vikrama, due to the presence of the kalpavriksha on the reverse it has not been possible to ascribe it to him.[14][15]

In anthropomorphic form

The rise of Tantrism aided the development of the anthropomorphic personification of the chakra as the active aspect of Vishnu with few sculptures of the Pala era bearing witness to the development,[16] with the chakra in this manner possibly associated with the Vrishnis.[8] However, the worship of Sudarshana as a quasi-independent deity concentrated with the power of Vishnu in its entirety is a phenomenon of the southern part of India; with idols, texts and inscriptions surfacing from the 13th century onwards and increasing in large numbers only after the 15th century.[16]

The Chakra Purusha in Pancharatra texts has either four, six, eight, sixteen, or thirty-two hands,[17] with double-sided images of multi-armed Sudarshana on one side and Narasimha on other side (called Sudarshana-Narasimha in Pancharatra) within a circular rim, sometimes in dancing posture found in Gaya area datable to 6th and 8th centuries.[18] Unique images of Chakra Purusha, one with Varaha in Rajgir possibly dating to the 7th century, [19] and another from Aphsad (Bihar) detailing a fine personification dating to 672 CE have been found.[20][21]

While the chakra is ancient, with the emergence of the anthropomorphic forms of chakra and shankha traceable in the north and east of India as the Chakra-Purusha and Shanka-Purusha; in the south of India, the Nayak period popularized the personified images of Sudarshana with the flames. In the Kilmavilangai cave is an archaic rock-cut structure in which an image of Vishnu has been hallowed out, holding the Shanka and Chakra, without flames.[22][23] At this point, the Chakrapurusha with the flames had not been conceived in the south of India. The threat of invasions from the north was a national emergency during which the rulers sought out the Ahirbudhnya Samhita, which prescribes that the king should resolve the threat by making and worshiping images of Sudarshana.[5]

Though similar motives induced the Vijayanagara period to install images of Sudarshana, there was a wider distribution of the cult during the Nayak period, with Sudarshana's images set up in temples ranging from small out-of-the-way ones to large temples of importance.[24] Though political turmoil resulted in the disintegration of the Vijayanagara empire, the construction and refurbishing of temples did not cease; with the Nayak period continuing with their architectural enterprises, which Begley and Nilakantha Sastri note "reflected the rulers' awareness of their responsibilities in the preservation and development of all that remained of Hinduism

The worship of Sudarshana Chakra is found in the Vedic and in the tantric cults. In the Garuda purana, the chakra was also invoked in tantric rites.[8] The tantric cult of Sudarshana was to empower the king to defeat his enemies in the shortest time possible.[16] Sudarshana's hair, depicted as tongues of flames flaring high forming a nimbus, bordering the rim of the discus and surrounding the deity in a circle of rays (Prabha-mandala) are a depiction of the deity's destructive energy.[16]

Representation

As a philosophy

Various Pancharatra texts describe the Sudarshan chakra as prana, Maya, kriya, shakti, bhava, unmera, udyama and saṃkalpa.[8] In the Ahirbudhanya Samhita of the Pancharatra, on bondage and liberation, the soul is represented as belonging to bhuti-shakti (made of 2 parts, viz., time (bhuti) and shakti (maya)) which passes through rebirths until it is reborn in its own natural form which is liberated; with the reason and object of samsara remaining a mystery. Samsara is represented as the 'play' of God even though God in the Samhita's representation is the perfect one with no desire to play. The beginning and the end of the play is effected through Sudarshana, who in the Ahirbudhanya Samhita is the will of the omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent God. The Sudarshana manifests in 5 main ways to wit the 5 Shaktis, which are creation, preservation, destruction, obstruction, and obscuration; to free the soul from taints and fetters which produce vasanas causing new births; so as to make the soul return to her natural form and condition which she shares with the supreme lord, namely, omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence.[25]

As a weapon

According to the Ahirbudhanya Samhita, "Vishnu, in the form of Chakra, was held as the ideal of worship for kings desirous of obtaining universal sovereignty",[26] a concept associated with the Bhagavata cult in the Puranas, a religious condition traceable to the Gupta period,[27] which also led to the chakravartin concept.[5] The concept of universal sovereignty possibly facilitated the syncretism of Krishna and Vishnu and reciprocally reinforced their military power and heroic exploits; with the kshatriya hero, Krishna preserving order in the phenomenal world while the composite Vishnu is the creator and upholder of the universe supporting all existence.[5] Begley notes the evolution of the anthropomorphic iconography of Sudarshana, beginning from early expansion of the Bhagavata sect thus:

"In contrast to the relatively simple religious function of the Cakra-Purusa, the iconographic role of the medieval Sudarsana-Purusa of South India was exceedingly complex. The medieval Sudarsana was conceived as a terrifying deity of destruction, for whose worship special tantric rituals were devised. The iconographic conception of Sudarsana as an esoteric agent of destruction constitutes a reassertion of the original militaristic connotation of the cakra".[5]

An early scriptural reference in obtaining the 'grace of Sudarshana' through building a temple for him can be found in the Ahirbudhanya Samhita, in the story of Kushadhvaja, a king of the Janakas, who felt possessed by the devil causing him various ills, due to a sin from his past life in killing a righteous king. His guru advises him to build the temple, following which he performs propitiatory rites for 10 days upon which he is cured.[25] However, the multi-armed Sudarsana as a horrific figure with numerous weapons standing on a flaming wheel comes from southern Indian iconography with the earliest example of the South Indian Sudarsana image being a small eight-armed bronze image from the 13th century.[5]

Chakraperumal

Chakra Perumal is the personified deification of Vishnu's Sudarshana Chakra. Though Chakraperumal or ChakkrathAzhwar shrines (sannidhis) are found inside Vishnu's temples, there are very few temples dedicated to Chakraperumal alone as the main deity (moolavar). The temple of Chakraperumal in Gingee on the banks of Varahanadi was one such temple.[28] However, it is not a functioning temple currently. In the present time, only 2 functioning temples with Chakraperumal as moolavar exist:

- Sri Sudarshana Bhagavan Temple, Nagamangala

- Chakrapani Temple, Kumbakonam - located on the banks of the Chakra bathing ghat of the Cauvery river. Here, the god is Chakrarajan and his consort is Vijayavalli.

The idols of Chakra Perumal are generally built in the Vijayanagar style. There are two forms of Sudarshana or Chakraperumal, one with 16 arms and another with 8 arms. The one with 16 arms is considered the god of destruction and is rarely found. The Chakraperumal shrine inside the Simhachalam Temple is home to the rare 16-armed form. The one with 8 arms is benevolent and is the form generally found in Vishnu's temples in present time. Chakraperumal was deified an avatar of Vishnu himself,[29] with the Ahirbudhnya Samhita identifying the Chakra-Purusha with Vishnu himself, stating Chakrarupi svayam Harih.[30]

The Simhachalam Temple follows the ritual of Baliharanna or purification ceremony. Sudarshana or Chakraperumal is the bali bera of Narasimha,[31] where he stands with 16 arms holding emblems of Vishnu with a circular background halo. Beside his utsava bera are the chaturbhuja thayar (mother goddess), Andal and Lakshminarayana in the bhogamandir.[31] In Baliharana, Chakra Perumal, the bali bera is taken to a yagnasala where a yagna is performed offering cooked rice with ghee while due murti mantras are chanted, along with the Vishnu Sukta and Purusha Sukta. Then he is taken on a palanquin around the temple with the remaining food offered to the guardian spirits of the temple.[31]

Sudarshan Homam

This homam is performed by invoking Lord Sudarshan along with his consort Vijayavalli into the sacrificial fire. This homam is very popular in South India.

Temples of Sudarshana

Most Vishnu temples have a separate shrine (sannidhi) for Sudarshana inside them. Some of them are:

- Sri Sudarshana Bhagavan Temple, Nagamangala

- Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangapatna

- Chakrapani Temple, Kumbakonam – Sudarshana is the main moolavar in this temple.

- Thirumohoor Kalamegaperumal temple, Madurai

- Varadharaja Perumal Temple, Kanchipuram

- Anjumoorthy (Five Deities) Temple, at Anjumoorthy Mangalam, in Palakkad district, Kerala – The main deity of this temple is Sudarshan.

- Thuravur (Alappuzha, Kerala) Narasimha temple, where narasimha and sudarshana are the main deities.

- Sree Vallabha Temple, Thiruvalla in Pathanamthitta district, Kerala

- Jagannath Temple, Puri, where Jagannatha, Subhadra, Balabhadra and Sudarshana are the main deities.

- Sri Narayanathu Kavu Sudarshana Temple, Tirur Kerala (family deity of Mangalassery).

- Shrinathji Temple

See also

- Ayudhapurusha

- Ahirbudhnya Samhita

- Chakra

- Chakram

- Chakri Dynasty of Thailand, named after this weapon.

- Sampo

Further reading

- Vishnu's Flaming Wheel: The Iconography of the Sudarsana-Cakra (New York, 1973) by W. E. Begley

- "Ancient Vishnu idol found in Russian town", Times of India (4 Jan 2007)

References

- Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 80.

- Monier Monier-Williams (1871). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, p. 310.

- Monier-Williams, Leumann E, Cappeller C, eds. (2002). "Chakra". A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages, p. 380. Motilal Banarsidass Publications.

- von Stietencron, Heinrich; Flamm, Peter (1992). Epic and Purāṇic bibliography: A-R. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 3447030283.

- Wayne Edison Begley. (1973). Viṣṇu's flaming wheel: the iconography of the Sudarśana-cakra, pp. 18, 48, 65–66, 76–77. Volume 27 of Monographs on archaeology and fine arts. New York University Press

- Agarwala, Vasudeva Sharana (1965). Indian Art: A history of Indian art from the earliest times up to the third century A.D, Volume 1 of Indian Art. Prithivi Prakashan. p. 101.

- Osmund Bopearachchi, Emergence of Viṣṇu and Śiva Images in India: Numismatic and Sculptural Evidence, 2016.

- Nanditha Krishna, (1980). The Art and Iconography of Vishnu-Narayana, p. 51.

- Handa, Devendra (2007). Tribal Coins of Ancient India. Aryan Books International. p. 140.

- Cunningham, Alexander (1891). Coins of Ancient India: From the Earliest Times Down to the Seventh Century. p. 70.

- Joshi, Nilakanth Purushottam (1979). Iconography of Balarāma. Abhinav Publications. p. 22.

- Sagar, Krishna Chandra (1992). Foreign Influence on Ancient India. Northern Book Centre. p. 94. ISBN 8172110286.

- "Jaya Cakravartindra Malla". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press: 702. 1908.

- Bajpai, K.D (2004). Indian Numismatic Studies. Abhinav Publications. p. 151. ISBN 8170170354.

- Agrawal, Ashvini (1989). Rise and Fall of the Imperial Guptas. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 23. ISBN 8120805925.

- Saryu Doshi, (1998). Treasures of Indian art: Germany's tribute to India's cultural heritage, p. 68. The National Museum of India.

- Parimoo, Ratan (2000). Essays in New Art History: Text. Volume 1 of Essays in New Art History: Studies in Indian Sculpture : Regional Genres and Interpretations. Books & Books. pp. 146–148. ISBN 8185016615.

- The Orissa Historical Research Journal, Volume 31, p. 90. Superintendent of Research and Museum, Orissa State Museum, 1985.

- Frederick M. Asher, 2008. Bodh Gaya: Monumental legacy, p. 90. Oxford University Press

- Col Ved Prakash, (2007). Encyclopaedia of North-East India, Volume 1, p. 375. Atlantic Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 8126907037

- See: http://vmis.in/ArchiveCategories/collection_gallery_zoom?id=491&search=1&index=30876&searchstring=india

- Jouveau-Dubreuil, G (1994). Pallava Antiquities. Asian Educational Services. p. 46. ISBN 8120605713.

- "Kilmavilangai Cave Temple". Retrieved 31 March 2017.

- Wayne Edison Begley (1973). Viṣṇu's flaming wheel: the iconography of the Sudarśana-cakra, p. 77. "attempt+to+resolve" Volume 27 of Monographs on archaeology and fine arts. New York University Press

- Otto, Schrader (1916). Introduction to the Pancaratra and the Ahirbudhnya Samhita. pp. 114–115, 135.

- Wayne Edison Begley (1973). Viṣṇu's flaming wheel: the iconography of the Sudarśana-cakra, p. 48. Volume 27 of Monographs on archeology and fine arts. New York University Press

- Śrīrāma Goyala, (1967). A history of the Imperial Guptas, p. 137. Central Book Depot.

- C.S, Srinivasachari (1943). History Of Gingee And Its Rulers.

- Jayaraj Manepalli (5 May 2006). "Vijayanagara period statues saved from rusting". Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- Swati Chakraborty, (1986). Socio-religious and cultural study of the ancient Indian coins, p. 102

- Sundaram, K. (1969). The Simhachalam Temple, pp. 42, 115. Published by the Simhachalam Devasthanam.