Isle of Mull

The Isle of Mull[6] (Scottish Gaelic An t-Eilean Muileach, pronounced [ən 'tjelan ˈmuləx]) or just Mull (English and Scots: [mʌl]; Scottish Gaelic: Muile, [ˈmulə] (![]()

| Gaelic name | Muile |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈmulə] ( |

| Norse name | Myl |

| Meaning of name | pre-Gaelic |

Tobermory waterfront | |

| Location | |

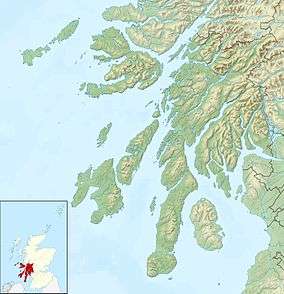

Isle of Mull Mull shown within Argyll and Bute | |

| OS grid reference | NM590354 |

| Coordinates | 56.45°N 6°W |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Mull |

| Area | 875.35 km2 (337.97 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 4 [1] |

| Highest elevation | Ben More 966 m |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Argyll and Bute |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,990 (2011 Census) |

| Population rank | 8 [1] |

| Population density | 3.2/km2 (8.3/sq mi) [2][3] |

| Largest settlement | Tobermory |

| References | [3][4][5] |

Covering 875.35 square kilometres (337.97 sq mi), Mull is the fourth-largest Scottish island and has the same rank as regards Great Britain. In the 2011 census the usual resident population was 2,800.[2] In 2001 the figure was 2,667.[7] In the summer these are supplemented by many tourists. Much of the population lives in colourful Tobermory, the only burgh on the island until 1973 and its capital.

Tobermory hosts Mull's only single malt Scotch whisky distillery, Tobermory distillery (formerly Ledaig).[8] The isle has numerous sports and the Highland Games competition in July. It also has at least four castles including the towering keep of Moy Castle. A much older stone circle is beside Lochbuie on the south coast.

Geography

Mull has a coastline of 480 km (300 mi), and its climate is moderated by the Gulf Stream. The island has a mountainous core; the highest peak on the island is Ben More, which reaches 966 m (3,169 ft). Various peninsulas, which are predominantly moorland, radiate from the centre.

The Aros peninsula to the north includes the main town of Tobermory, which was a burgh until 1973 when burghs were abolished. Other settlements include Salen, Dervaig and Calgary. The Ross of Mull lies to the south-west and includes the villages of Bunessan, Pennyghael, Uisken, and Fionnphort. Lochbuie, Lochdon, and Craignure lie to the east.

Numerous islands lie off the west coast of Mull, including Erraid, Inch Kenneth, Iona, Gometra, and Ulva. Smaller uninhabited islands include Eorsa, Little Colonsay, the Treshnish Isles, and Staffa (of Fingal's Cave fame). Calve Island is an uninhabited island in Tobermory Bay. Two outlying rock lighthouses are also visible from the south-west of Mull, Dubh Artach and Skerryvore. The Torran Rocks are a large shoal of reefs, islets, and skerries, approximately 15 square miles (39 square kilometres) in extent, two miles (three kilometres) to the south-west, between the Ross of Mull peninsula and Dubh Artach. Frank Lockwood's Island near Lochbuie is named after Frank Lockwood, the brother-in-law of the 21st MacLean of Lochbuie and Solicitor General from 1894 to 1895.[9]

Part of the indented west coast of Mull and some of the offshore islands there are part of the Loch Na Keal National Scenic Area.[10]

History

Early history

The Isle of Mull has probably been inhabited since shortly after the end of the last Ice Age, around 11000 years ago. This is evidenced by radio carbon dating from a mesolithic hut at Crieth Dubh on the northwest coast of the island.[11] Later, Bronze Age and Iron Age inhabitants built brochs at Dun Nan Gall [12] and An Sean Chaisteal [13], and a stone circle at Lochbuie [14] along with numerous examples of burial cairns.[15] Two crannogs have been dated to the Iron Age.[16]

In the 6th century AD, Irish migrants invaded Mull and the surrounding coast, establishing the Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riata. The kingdom was divided into a number of regions, each controlled by a kin group, of which the Cenél Loairn controlled Mull and the adjacent mainland to the east. Dál Riata was a springboard for the Christianisation of the mainland; the pivotal point was AD 563, when Columba, an Irish missionary, arrived at the island of Iona just off the south-west point of Mull and founded a monastery from which to start evangelising the local population.[17]

Norse period

In the 9th century, Viking invasions led to the destruction of Dál Riata and its replacement by the Norse Kingdom of the Isles, which became part of the kingdom of Norway following Norwegian unification around 872. The Kingdom of the Isles was much more extensive than Dál Riata, encompassing also the Outer Hebrides and Skye. The island kingdom became known as the Suðreyjar, meaning southern isles in Old Norse. The former lands of Dál Riata acquired the geographic description "Argyle" (now "Argyll"): the Gaelic coast.

In the late 11th century, Magnus Barefoot, the Norwegian king, launched a military campaign which in 1098 led the king of Scotland to quitclaim to Magnus all claim of sovereign authority over the territory of the Kingdom of the Isles.[18] However, a coup some 60 years later, led by a Norse-Gael named Somerled, detached the whole of the Suðreyjar from Norway and transformed it into an independent kingdom. After Somerled's death in 1164, nominal Norwegian authority was established, but practical control of the realm was divided between Somerled's sons and the heirs of Somerled's brother-in-law, the Crovan Dynasty. His son Dougall received the former territory of the Cenél Loairn, now known as Lorn, of which Mull formed part.[19]

Meanwhile, the Crovan dynasty had retained the title "king of the Isles" and control of Lewis, Harris, and the Isle of Man. After a few decades, they acknowledged the English kings as their overlords, so Dougall's heirs (the MacDougalls) complained to Haakon, the Norwegian king, and in 1237 were rewarded by the kingship being split; rule of the Hebrides was transferred to the MacDougall line, and they were made the "kings of the Hebrides". They established the twin castles of Aros (in Mull) and Ardtornish (on the mainland, opposite), which together controlled the Sound of Mull.

Throughout the early 13th century, the king of Scots, Alexander II, had aggressively tried to expand his realm into the Suðreyjar, despite Edgar's earlier quitclaim. This led to hostility between Norway and Scotland, which continued under Alexander III. King Haakon IV of Norway died shortly after the indecisive Battle of Largs. In 1266, his more peaceable successor ceded his nominal authority over the Suðreyjar to Alexander III by the Treaty of Perth in return for a very large sum of money. Alexander generally acknowledged the semi-independent authority of Somerled's heirs; the former Suðreyjar had become Scottish crown dependencies rather than parts of Scotland.

Lords of the Isles

At the end of the 13th century, a violent dispute arose over the Scottish kingship between King John Balliol and Robert de Bruys. By then, Somerled's descendants had formed into three families: as well as Dougall's heirs (the MacDougalls), there were also the heirs of his nephew Donald (the MacDonalds) and those of Donald's brother (the MacRory); the MacDougalls backed Balliol, while the MacDonalds and MacRory backed de Bruys. When de Bruys defeated John, he declared the MacDougall lands forfeit and gave them to the MacDonalds and MacRory, with the latter acquiring Lorn (and hence, Mull). John of Islay, the head of the MacDonald family, then married Amy of Garmoran. the heir of the MacRory family, thereby consolidating the remains of Somerled's realm, and transforming it into the Lordship of the Isles.

In 1354, though in exile and without control of his ancestral lands, John, the MacDougall heir, quitclaimed any rights he had over Mull to the Lord of the Isles. When Robert's son David II became king, he spent some time in English captivity; after his release, in 1357, he restored MacDougall authority over Lorn, effectively cancelling Robert's grant to the MacRory. The 1354 quitclaim, which seems to have been an attempt to ensure peace in just such an eventuality, took automatic effect, splitting Mull from Lorn and making it subject to the Lordship of the Isles.

In 1437, the Lordship was substantially expanded when Alexander, the Lord of the Isles, inherited the rule of Ross maternally. The expansion led the MacDonalds to move their centre of power from Islay to the twin castles of Aros and Ardtornish.

In 1462, the most ambitious of the Lords of the Isles, John MacDonald, struck an alliance with Edward IV of England to conquer Scotland. Civil war in England prevented this from taking effect and from being discovered until 1475, when the English court voluntarily revealed its existence. Calls for forfeiture of the Lordship naturally followed, but they were calmed when John quitclaimed most of his mainland territories. However, John's nephew launched a severe raid on Ross, but it ultimately failed. Within two years of the raid, in 1493, James IV of Scotland declared the Lordship of the Isles forfeit, transforming the realm into an intrinsic part of Scotland rather than a dependency.

MacLeans

Throughout this time, the descendants of the Cenél Loairn retained their identity; they were now the MacLeans. Now that John MacDonald was exiled, James IV restored the authority of the MacLeans over Mull. An earlier chief of the MacLeans had married the daughter of the first Lord of the Isles and received Duart Castle as the dowry; this now became the stronghold of MacLean control of Mull. The cadet branch of the family constructed a tower house at Moy on the southern side of Mull, while the senior branch retained Duart Castle.

Legend has it that the wreck of a Spanish galleon, laden with gold, lies somewhere in the mud at the bottom of Tobermory Bay. By some accounts, the Florencia (or Florida or San Francisco), a ship of the defeated Spanish Armada fleeing the English fleet in 1588, anchored in Tobermory to take on provisions. After a dispute over payment, the ship caught fire and the gunpowder magazine exploded, sinking the vessel. In her hold, reputedly, was £300,000 in gold bullion.[20] Other sources claim the vessel was the San Juan de Sicilia (or San Juan de Baptista), which carried troops, not treasure.[21] According to that account, the island's chief, Lachlan Mor Maclean, struck a deal with the Spanish commander to re-provision and refit the ship in return for military intervention on the side of the MacLeans in their feud with enemies on nearby islands.[22] There have been numerous searches for the wreck and its rumoured treasure from the mid-17th century to the end of the 20th century.[23] No significant treasure has been recovered in Tobermory Bay.[24]

Following the Scottish Reformation, the MacLeans became supporters of Protestantism. By the mid-17th century, they had become promoters of conventicles, opposed to king Charles II's repudiation of the Solemn League and Covenant and supporting acts of civil disobedience. Though personally opposed to persecution of such people, Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, was specifically ordered by the Scottish privy council to suppress conventicles within his lands, which included Lorn. The atmosphere of hostility soon spread to Mull, where opponents of the conventicles felt emboldened, leading to outbreaks of violence between the two religious factions.

In 1678, Campbell was specifically instructed to seize Mull and suppress both the violence and conventicles. It took him until 1680 to gain possession of the whole island. Campbell took charge of Duart Castle and ejected the MacLean leadership from Mull; they moved to Cairnburgh Castle in the Treshnish Islands off the north-west of Mull. Campbell's own position was somewhat undermined when he instigated Argyll's Rising against the reign of James VII. The loyalty of subsequent Campbell leaders ensured the Campbells retained possession of Duart (it was only after the Campbells sold it, and it had spent a century under other owners, that the MacLeans were able to recover it by purchase). Under Campbell pressure, shrieval authority was established under the sheriff of Argyll, which they controlled.

Later history

Following Jacobite insurrections, the Heritable Jurisdictions Act abolished comital authority in Mull and Campbell control of the Argyll sheriffdom; the Campbells could now only assert influence as landlords. Many castles that had been in the hands of the MacLeans (such as Moy) had been slighted by the Campbells or fallen into disrepair, but more comfortable homes were built nearby.

During the 18th century, the island was home to a Gaelic Bard, whom Father Charles MacDonald describes only as "The Mull Satirist." The Satirist is said to have been a vocal enemy of the Jacobite Bard Alasdair Mac Mhaighstir Alasdair and to have attacked the latter in many poems that have survived. When the Jacobite poet converted from the Calvinist Church of Scotland to the Roman Catholic Church, the Mull Satirist accused him of doing so, not out of serious conviction, but to curry favour with the exiled House of Stuart.[25]

In 1773 the island was visited by Samuel Johnson and James Boswell during their tour of the Western Islands. Farming, fishing, and burning seaweed for kelp ash (used in the manufacture of soap and glass) were the main economic activities on the island until the 19th century. Tobermory was built by the British Fisheries Society in 1788 as a planned settlement to support the fishing industry. Following the Highland Clearances in the 18th and 19th centuries and the Highland Potato Famine, the population fell from 10,000 to less than 3,000, and the island economy collapsed. Despite this, several grand houses were built on Mull in the period, including Torosay Castle. By the early 20th century there were more sheep than people.

In 1889, counties were formally created in Scotland on shrieval boundaries by a dedicated Local Government Act; Mull therefore became part of the newly created County of Argyll.

The whole island became a Restricted Area during World War II. The bay at Tobermory became a naval base commanded from HMS Western Isles. The base and the Restricted Area were under Commodore (later Vice Admiral) Sir Gilbert Stephenson, whose strict discipline and ferocious temper earned him the nickname "The Terror of Tobermory".[26] The base was used to train Escort Groups in anti-submarine warfare. 911 ships passed through the base between 1940 and 1945. Following late 20th century reforms, Mull is now part of the wider area of Argyll and Bute.

Gaelic language

In Mull and the adjacent islands Gaelic had been the traditional language since the early Middle Ages. The twentieth century in particular saw a reduction in the number of speakers, with a significant fall (20%) in Mull after the Second World War. This was associated with strong emigration and abandonment of the language by the younger generation. In the 1951 census only 10 people said they could not speak English.[27]

The following decades saw the beginnings of a revival. Gaelic medium education was introduced in 1996 after a long dispute with the authorities. A Gaelic medium unit was introduced in the local school, the language began to be taught in the first two years of secondary school and Gaelic playgroups were introduced. By 2006 it was found that, though only 10% of the working age cohort spoke or understood Gaelic, language ability at school age was much higher. There was great local variation in the number of speakers, from around 25% in Creag an Iubhair (Craignure) to 4% in Aros. It has been argued, however, that in terms of language survival, there is reason for optimism in Mull.[27]

Economy

The economy began to revive when the construction of Craignure Pier in 1964 started to bring tourists. Tourism is now the mainstay of the island's economy. Ecotourism became popular from the 1990s, and the reintroduction of white-tailed eagles in 2005 became a particular ecotourist attraction.[28]

There is a small amount of farming, aquaculture, and fishing, and Forestry and Land Scotland has several plantations on the island. Tobermory also has one whisky distillery (Tobermory distillery) and from 2005 to 2009 had a brewery (Isle of Mull Brewing Company).[29]

Isle of Mull cheese is Scottish cheddar cheese made from raw cow milk produced on the Isle of Mull.[30]

Transport

Ferries

Ferry links to Mull from the mainland include:

- the most-used ferry, from Oban to Craignure (approx. 45 minutes),

- Kilchoan to Tobermory (approx. 35 minutes)

- Lochaline to Fishnish (approx. 15 minutes).

Advance bookings are not required for the Kilchoan or Fishnish ferries; access to those two ferry terminals on the mainland side is via single-track roads.

There are also ferry links from Fionnphort on Mull to the neighbouring island of Iona and from Oskamull to Ulva. In past years there were direct sailings to Oban (calling at Drimnin, Salen, Lochaline, and Craignure), and to Barra, Coll, and Tiree from Tobermory. During the summer there was also a sailing to Staffa and Iona from Oban that called at Tobermory.

Buses

Buses are operated by West Coast Motors Ltd. There are routes from Tobermory to Calgary via Dervaig (Service 494), Tobermory to Craignure via Salen (Service 495), and Craignure to Fionnphort via Bunessan (Service 496). Limited services operate to Lochbuie and Gruline.[31] West Coast Motors also provide guided tours around Mull, Iona, and Staffa, including boat transfers from Oban.

A minibus service also operates seasonally from Craignure to Duart Castle.[32]

There is also a community-run service from Calgary to Salen via Ulva Ferry.[33]

Airstrip

There is a landing strip for private light aircraft near Salen.[34] There was a seaplane that linked Tobermory with Glasgow and Oban. The regular scheduled service terminated in 2009. Loganair operated a scheduled service to Glasgow in the 1960s from Glenforsa airfield, a 780-metre-long (2,560 ft) grass airstrip constructed by the Royal Engineers in 1965 near Salen. The airstrip has been operated since 2014 by Brendan and Allison Walsh, owners of the adjacent Glenforsa Hotel.

Tourist railway

The Isle of Mull Railway ran from Craignure to Torosay Castle but closed in 2011.

Schooling

There is one secondary school on the island (Tobermory High School, which includes a Gaelic medium education unit) and six primary schools. Salen Primary School has a Gaelic medium education unit. Secondary pupils (age 11 - 18) from Iona, Bunessan and Fionnphort in the south-west attend Oban High School, staying in an Oban hostel from Monday to Thursday.

Communications

Mull was connected to the mainland by a submarine telegraph cable between Oban and Grass Point in 1871. There were telegraph offices at Tobermory, Dervaig, Calgary, Craignure, Pennyghael, Tiroran, Fionnphort, Bunessan, and Iona.[35]

The Post Office built an experimental wireless telegraph station on Meall an Inbhire near Tobermory in 1892.[36]

In 2014, fibre optic cables for support of high speed internet were laid between Kilchoan (in Ardnamurchan) and Tobermory and between Dunstaffnage (near Oban) and Torosay. In February 2015 additional cables were laid underground between Tobermory and Torosay to complete the link.

Media and the arts

AM radio, broadcast from Oban, came to the island in 1930 and television in 1954. New AM radio and UHF television transmitters were constructed on Druim Mòr, one mile (1.6 km) west of Torosay Castle, in 1978. Digital transmissions commenced on 15 November 1998 and analogue transmissions ceased on 27 October 2010. The digital transmitters have 22 relays on Mull, surrounding islands, and parts of the mainland, collectively the Torosay Transmitter Group.[37]

Mull Theatre is a professional theatre company based in a 2008 theatre production centre on the outskirts of Tobermory.[38] The company commissions plays, tours throughout Scotland and beyond, and runs an education and outreach programme. It started at the "Mull Little Theatre" at Dervaig in 1966 and was the "Smallest Professional Theatre in the World" according to the Guinness World Records. The National Theatre of Scotland were in residence at the Mull Theatre in April 2009.

An Tobar ("The Well"), based in Tobermory, is the only publicly funded multidisciplinary arts centre in Argyll. Established in 1997, it is a centre for visual arts, crafts and music.[39] With effect from 1 April 2013, An Tobar and the Mull Theatre were brought together as Comar.

Natural history

The Isle of Mull is a popular destination for naturalists and photographers for seeing some of Britain's more elusive species.

Mull has over 800 species of vascular plant (684 native and 171 naturalised) including 33 species of fern,[40] at least 18 species of orchid and 22 native species of tree. There are about 700 species of lichen, 571 liverworts and mosses, and 247 marine algae (seaweeds), making a total of 2,388 species of plant recorded from the island. In addition, more than 2,000 species of fungi have been recorded on Mull: Dennis and Watling write, "When one speaks of the Inner Hebridean fungi one is referring to the floras of Mull and Rhum".[41]

The island has 261 different bird species, including the white-tailed eagle, which was reintroduced to the nearby island of Rùm and migrated to Mull, where it now has a stronghold. Basking sharks, minke whales, porpoises, and dolphins are among the sea life nearby.

The island is home to a population of otters that live in coastal habitat, hunting during the day.[42] The Mull Otter Group was established for the conservation needs of otters on the Isle of Mull.[43]

The island also has several birds of prey, such as hen harriers,[44] golden eagles,[45] and short eared owls,[46] all difficult species to see throughout the rest of the UK. Pine martens have also recently become established on Mull;[47] based on sighting records and from resulting modelling exercises, it is believed the species arrived in 2004 through accidental transportation on timber boats from the mainland. It is unlikely that pine martens have ever been native to the Isle of Mull.[48]

The Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust was established in 1994 as a registered charity for education and monitoring programmes on cetaceans in the Hebrides.[49] The trust is based at Tobermory, where it has its main, education, and research offices and a visitor centre.

There are also a number of invasive species on the island, including plant species such as Japanese knotweed[50] and animals such as feral cats and American mink[51] that are believed to be causing damage to the indigenous species populations through competition and predation.[40]

Sport

The Tour of Mull is a road-closing rally around the island every October. It has been sponsored since 2005 by Tunnock's, the Lanarkshire teacake and biscuit manufacturer.[52] A five-year sponsorship deal with Beatson's Building Supplies started in 2015.

There are several shipwrecks around the shores that offer scuba diving.

There is an Isle of Mull Cycling Club.

The Cross at the Castle cyclocross event is held annually at Glengorm Castle near Tobermory and features the World Santacross Championships and the Scottish Singlespeed Cylocross Championships.

Mull Runners organise a half marathon and 10K run each August between Craignure and Salen.

Rugby is played at Garmony (beside the Craignure to Salen road 6.5 miles north of Craignure). The Mull Rugby 7s Competition takes place annually in May at The Isle of Mull R.F.C's rugby club.

There are golf courses at Tobermory (Erray Park), Craignure (beside the Craignure to Salen road a mile north of Craignure) and on Iona.

Mull Highland Games are held each July in the grounds of Tobermory Golf Club (Erray Park). Events include Heavy Weights, Light Field, and Highland Dance.

The swimming pool at the Isle of Mull Hotel, Craignure is open to the paying public.

Tobermory has some free tennis courts.

Football is played, mainly in the south end. Bunessan F.C. play a number of games during the summer, most notably against arch rivals Iona FC, the island just off the south west end. Bunessan F.C. also hold an annual 5-a-side tournament in July.

Community initiatives

Following research and community consultation in 1996/97, a development trust was created to identify key goals for the communities of Mull and Iona. Mull & Iona Community Trust[53] was formed in 1997 and published a "Community Regeneration Strategy" for the islands. They purchased the only butcher's shop on the island (closed February 2010), created a community-run Countryside Ranger service, instigated various recycling initiatives, and provide a fundraising and training consultancy.[54]

.jpg)

Notable people connected to Mull

- Duncan Livingstone (1877-1964) Scottish Gaelic Bard, born at Torloisk, emigrated to South Africa in 1903. Continued to write Gaelic verse in Pretoria until his death.

- Agnes Maxwell MacLeod (1783-1879) poet and minister's wife

- Margaret McKellar (1861–1941), medical missionary[55]

- Norman Maclean (1902-1990), Scottish-American author who explored the legacy of his Mull ancestors in the 1976 novella A River Runs Through It and Other Stories.

- Mary Macleod, 17th-century poet said to have been banished to Mull.[56]

- Lachlan Macquarie, (1762-1824), born on the nearby island of Ulva.[57]

- Major General Colin Gubbins, head of Special Operations Executive during World War II

- Peter Bonetti, (1941-2020), English footballer (goalkeeper)

See also

References

- Baird, Bob (1995) Shipwrecks of the West of Scotland. Glasgow. Nekton Books. ISBN 1-897995-02-4

- Currie, Jo. (2001) Mull: The Island and Its People. Birlinn Ltd.

- Jermy, A.C. and Crabbe, J.A. (Ed) (1978) The Island of Mull a Survey of its Flora and Environment. London. British Museum (Natural History).

Footnotes

- Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland's Inhabited Islands" (PDF). Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland Release 1C (Part Two) (PDF) (Report). SG/2013/126. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

- Ordnance Survey. OS Maps Online (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure.

- Anderson, Joseph (Ed.) (1893) Orkneyinga Saga. Translated by Jón A. Hjaltalin & Gilbert Goudie. Edinburgh. James Thin and Mercat Press (1990 reprint). ISBN 0-901824-25-9

- "Isle of Mull". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- Tobermory Distillery tobermory.co.uk Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- Baird (1995) p. 142

- "National Scenic Areas" Archived 11 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine. SNH. Retrieved 30 Mar 2011.

- Mithen, S., Wicks, K., Berg-Hansen, I.M. 2020 The Mesolithic coastal exploitation of western Scotland: The impacts of climate change and use of favoured locations. In: Schülke, A. (ed) Coastal Landscapes of the Mesolithic. Abingdon: Routledge

- "Dun Nan Gall, Mull | Canmore".

- "An Sean Chaisteal, Ardnacross, Mull | Canmore".

- "Mull, Lochbuie | Canmore".

- Fisher, P., Farrelly, C. (1997), p.585

- Holley, M.W., Ralston, I.B.M. 1995. Radiocarbon dates for two crannogs on the Isle of Mull, Strathclyde Region, Scotland. Antiquity 69(264), 595-596

-

- Susan Crane (29 November 2012). Animal Encounters: Contacts and Concepts in Medieval Britain. University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-8122-0630-2.

- Nicholas Ostler (23 February 2016). Passwords to Paradise: How Languages Have Re-invented World Religions. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-62040-517-8.

- Norbert Brockman (13 September 2011). Encyclopedia of Sacred Places. ABC-CLIO. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-59884-654-6.

- Ó Corráin, D. 2008. The Vikings and Ireland. In Brink, S. (ed) The Viking World. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sellar, W., Hamilton, D. 2000. Hebridean sea kings: The successors of Somerled, 1164–1316. In Cowan, E.J., McDonald, R.A. (eds.) Alba: Celtic Scotland in the middle ages. Tuckwell Press.

- A Clan Feud, a Spanish Galleon, and a Big Bang. lostfort.blogspot.com Retrieved 10 July 2010.

-

- The Galleon San Francisco. shipmodeling.net Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- The Tobermory Wreck. news.scotsman.com Retrieved 2010-07-10.

-

- Martin, Colin; Parker, Geoffrey (1988), The Spanish Armada, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, p. 244, ISBN 978-0-393-02607-8

- Campbell of Airds, Alastair (2002), A History of Clan Campbell; Volume 2; From Flodden to the Restoration, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, p. 95, ISBN 978-1-902930-18-3

- Lewis, Michael (1960), The Spanish Armada, London: B. T. Batsford Ltd

- Martin, Colin (1975), Full Fathom Five: Wrecks of the Spanish Armada, New York: The Viking Press, p. 58, ISBN 978-0-670-33193-2

- Tobermory Bay. reese.org Archived 21 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 2010-07-10.

- MacDonald (2011), Moidart: Among the Clanranalds, page 132.

- Baker, Richard (1972). The Terror of Tobermory: Vice-Admiral Sir Gilbert Stephenson, KBE, CB, CMG. W.H. Allen. ISBN 978-1-84158-197-2.

- Kurt C. Duwe, “Muile, Tiriodh & Colla”, Vol. 20, Gàidhlig (Scottish Gaelic) Local Studies, 2006: http://www.linguae-celticae.org/dateien/Gaidhlig_Local_Studies_Vol_20_Muile_Tiriodh_Ed_II.pdf

- "Wildlife at work: The economic impact of white-tailed eagles on the Isle of Mull" (PDF). Royal Society for the Protection of Birds. 3 March 2011.

- "Isle of Mull Brewing Company". Today's Breweries. ScottishBrewing.com. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- Cheese For Dummies - Culture Magazine, Laurel Miller, Thalassa Skinner. p. 144.

- "Timetables & maps - West Coast Motors". Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ulva Ferry Community Bus". Retrieved 14 February 2019.

- "Transport Links" The Glen Forsa Hotel. Retrieved 14 July 2008.

- P. A. Macnab (1970). The Isle of Mull. David & Charles. p. 129.

- "Electrical engineering". 9. 1913: 623. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Torosay and relays". UK Free TV. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- "Druimfin, the new home for Mull Theatre". Mull Theatre. Retrieved 26 July 2009.

- "Welcome to AN TOBAR, Tobermory, Isle of Mull" antobar.co.uk. Retrieved 21 June 2010.

- "Home - Wild Mull". Archived from the original on 22 December 2015.

- Dennis, R.W.G., Watling, R. 1983. Fungi in the Inner Hebrides. In The Natural Environment of the Inner Hebrides, Edited by John Morton Boyd and D.R. Bowes, Volume 83, January 1983, pp 415-429

- "Lutra lutra". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Mull Otter Group". Mull Otter Group. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Circus cyaneus". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Aquila chrysaetos". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Asio flammeus". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Martes martes Wild Mull". Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- Roy, S., Milborrow, J., Allan, J. and Robertson, P. 2012. Pine martens on the Isle of Mull – Assessing risks to native species. Scottish Natural Heritage Commissioned Report No.560

- "Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust". Hebridean Whale and Dolphin Trust. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Reynoutria japonica". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

- "Neovison vison". Wild Mull. Retrieved 24 October 2015.

-

- "Tunnock's Tour of Mull" 2300club.org. Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- "Tour of Mull Rally 1969-2002" Archived 19 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine Mullcarclub.co.uk. Retrieved 27 September 2008.

- "Mull and Iona Community Trust".

- DTA Scotland Directory of Members Archived 3 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Leonard, John William (1914). Woman's Who's who of America: A Biographical Dictionary of Contemporary Women of the United States and Canada. American Commonwealth Company. pp. 524–.

- Thomson, Derick S. "Màiri nighean Alasdair Ruaidh". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/17675. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- McLachlan, N. D. (1967). "Macquarie, Lachlan (1762–1824)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Melbourne University Press. ISSN 1833-7538. Retrieved 7 June 2009 – via National Centre of Biography, Australian National University.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Isle of Mull. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mull. |