Basking shark

The basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) is the second-largest living shark, after the whale shark, and one of three plankton-eating shark species, along with the whale shark and megamouth shark. Adults typically reach 7.9 m (26 ft) in length. It is usually greyish-brown, with mottled skin. The caudal fin has a strong lateral keel and a crescent shape.

| Basking shark | |

|---|---|

| |

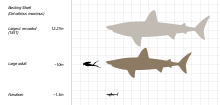

| The size of basking sharks at various stages of growth and maturity with a human for scale | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Lamniformes |

| Family: | Cetorhinidae T. N. Gill, 1862 |

| Genus: | Cetorhinus Blainville, 1816 |

| Species: | C. maximus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cetorhinus maximus (Gunnerus, 1765) | |

| |

| Range of the basking shark | |

| Synonyms | |

|

click to expand

| |

The basking shark is a cosmopolitan migratory species, found in all the world's temperate oceans. A slow-moving filter feeder, its common name derives from its habit of feeding at the surface, appearing to be basking in the warmer water there. It has anatomical adaptations for filter-feeding, such as a greatly enlarged mouth and highly developed gill rakers. Its snout is conical and the gill slits extend around the top and bottom of its head. The gill rakers, dark and bristle-like, are used to catch plankton as water filters through the mouth and over the gills. The teeth are numerous and very small, and often number 100 per row. The teeth have a single conical cusp, are curved backwards, and are the same on both the upper and lower jaws. This species has the smallest weight-for-weight brain size of any shark, reflecting its relatively passive lifestyle.[3]

Basking sharks have been shown from satellite tracking to overwinter in both continental shelf (less than 200 m or 660 ft) and deeper waters.[4] They may be found in either small shoals or alone. Despite their large size and threatening appearance, basking sharks are not aggressive and are harmless to humans.

The basking shark has long been a commercially important fish, as a source of food, shark fin, animal feed, and shark liver oil. Overexploitation has reduced its populations to the point where some have disappeared and others need protection.[5]

Taxonomy

The basking shark is the only extant member of the family Cetorhinidae, part of the mackerel shark order Lamniformes. Johan Ernst Gunnerus first described the species as Cetorhinus maximus, from a specimen found in Norway, naming it. The genus name Cetorhinus comes from the Greek ketos, meaning "marine monster" or "whale", and rhinos, meaning "nose". The species name maximus is from Latin and means "greatest". Following its initial description, more attempts at naming included: Squalus isodus, in 1819 by Italian Zoologist Saverio Macri (1754–1848); Squalus elephas, by Charles Alexandre Lesueur in 1822; Squalus rashleighanus, by Jonathan Couch in 1838; Squalus cetaceus, by Laurens Theodorus Gronovius in 1854; Cetorhinus blainvillei by the Portuguese biologist Felix Antonio De Brio Capello (1828–1879) in 1869; Selachus pennantii, by Charles John Cornish in 1885; Cetorhinus maximus infanuncula, by the Dutch Zoologists Antonius Boudewijn Deinse (1885–1965) and Marcus Jan Adriani (1929–1995) in 1953; and Cetorhinus maximus normani, by Siccardi in 1961.[6] Other common names include bone shark, elephant shark, sail-fish, and sun-fish. In Orkney, it is commonly known as hoe-mother (sometimes contracted to homer), meaning "the mother of the pickled dog-fish".[7]

Range and habitat

The basking shark is a coastal-pelagic shark found worldwide in boreal to warm-temperate waters. It lives around the continental shelf and occasionally enters brackish waters.[8] It is found from the surface down to at least 910 m (2,990 ft). It prefers temperatures of 8 to 14.5 °C (46.4 to 58.1 °F), but has been confirmed to cross the much-warmer waters at the equator.[9] It is often seen close to land, including in bays with narrow openings. The shark follows plankton concentrations in the water column, so is often visible at the surface.[10] It characteristically migrates with the seasons.[11]

Anatomy and appearance

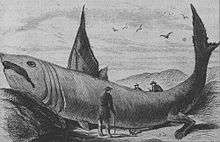

The largest accurately measured specimen was trapped in a herring net in the Bay of Fundy, Canada, in 1851.[12] Its total length was 12.27 m (40.3 ft), and it weighed an estimated 16 t (16 long tons; 18 short tons).[13][14] Dubious reports from Norway mention three basking sharks over 12 m (39 ft), the largest at 13.7 m (45 ft), during 1884 to 1905,[15] these are dubious because few anywhere near that size have been caught in the area since. On average, the adult basking shark reaches a length of 7.9 m (26 ft) and weighs about 4.65 t (4.58 long tons; 5.13 short tons).[14] Some specimens still surpass 9–10 m (30–33 ft), but after years of large-scale fishing, specimens of this size have become rare.

They possess the typical shark lamniform body plan and have been mistaken for great white sharks.[16] The two species can be easily distinguished by the basking shark's cavernous jaw, up to 1 m (3 ft 3 in) in width, longer and more obvious gill slits that nearly encircle the head and are accompanied by well-developed gill rakers, smaller eyes, much larger overall size and smaller average girth. Great whites possess large, dagger-like teeth; basking shark teeth are much smaller 5–6 mm (0.20–0.24 in) and hooked; only the first three or four rows of the upper jaw and six or seven rows of the lower jaw function. In behaviour, the great white is an active predator of large animals and not a filter feeder.

Other distinctive characteristics include a strongly keeled caudal peduncle, highly textured skin covered in placoid scales and a mucus layer, a pointed snout—distinctly hooked in younger specimens—and a lunate caudal fin.[17] In large individuals, the dorsal fin may flop to one side when above the surface. Colouration is highly variable (and likely dependent on observation conditions and the individual's condition): commonly, the colouring is dark brown to black or blue dorsally, fading to a dull white ventrally. The sharks are often noticeably scarred, possibly through encounters with lampreys or cookiecutter sharks. The basking shark's liver, which may account for 25% of its body weight, runs the entire length of the abdominal cavity and is thought to play a role in buoyancy regulation and long-term energy storage.

Life history

Basking sharks do not hibernate, and are active year-round.[18] In winter, basking sharks often move to deeper depths, even down to 900 m (3,000 ft) and have been tracked making vertical movements consistent with feeding on overwintering zooplankton.[19]

Surfacing behaviors

They are slow-moving sharks (feeding at about 2 knots (3.7 kilometres per hour; 2.3 miles per hour))[20] and do not evade approaching boats (unlike great white sharks). They are not attracted to chum.

Though the basking shark is large and slow, it can breach, jumping entirely out of the water.[21] This behaviour could be an attempt to dislodge parasites or commensals.[11] Such interpretations are speculative, however, and difficult to verify; breaching in large marine animals such as whales and sharks might equally well be intraspecific threat displays of size and strength.

Migration

Argos system satellite tagging of 20 basking sharks in 2003 confirmed basking sharks move thousands of kilometres during the summer and winter, seeking the richest zooplankton patches, often along ocean fronts.[22][23] They shed and renew their gill rakers in an ongoing process, rather than over one short period.[24]

A 2009 study tagged 25 sharks off the coast of Cape Cod, Massachusetts, and indicated at least some migrate south in the winter. Remaining at depths between 200 and 1,000 metres (660 and 3,280 ft) for many weeks, the tagged sharks crossed the equator to reach Brazil. One individual spent a month near the mouth of the Amazon River. They may undertake this journey to aid reproduction.[9][25]

On 23 June 2015, a 6.1-metre-long (20 ft), 3,500-kilogram (7,716 lb) basking shark was caught accidentally by a fishing trawler in the Bass strait near Portland, Victoria, in southeast Australia, the first basking shark caught in the region since the 1930s, and only the third reported in the region in 160 years.[26][27] The whole shark was donated to the Victoria Museum for research, instead of the fins being sold for use in shark fin soup.[28][29]

While basking sharks are not infrequently seen in the Mediterranean Sea[30] and records exist in the Dardanelles Strait,[31] it is unclear whether they historically reached into deeper basins of Sea of Marmara, Black Sea and Azov Sea.

Social behavior

Basking sharks are usually solitary but during summer months in particular they aggregate in dense patches of zooplankton where they engage in social behaviour. They can form sex-segregated shoals, usually in small numbers (three or four), but reportedly up to 100 individuals.[11] Small schools in the Bay of Fundy and the Hebrides have been seen swimming nose to tail in circles; their social behavior in summer months has been studied and is thought to represent courtship.[32]

Predators

Basking sharks have few predators. White sharks have been reported to scavenge on the remains of these sharks. Killer whales have been observed feeding on basking sharks off California and New Zealand. Lampreys are often seen attached to them, although they are unlikely to be able to cut through the shark's thick skin.

Diet

The basking shark is a ram feeder, filtering zooplankton, very small fish, and invertebrates from the water with its gill rakers by swimming forwards with their mouths open. A 5-metre-long (16 ft) basking shark has been calculated to filter up to 500 short tons (450 t) of water per hour swimming at an observed speed of 0.85 metres per second (2.8 ft/s).[24] Basking sharks are not indiscriminate feeders on zooplankton. Samples taken in the presence of feeding individuals recorded zooplankton densities 75% higher compared to adjacent non-feeding areas.[33] Basking sharks feed preferentially in zooplankton patches dominated by small planktonic crustaceans called calanoid copepods (on average 1,700 individuals per cubic metre of water). Basking sharks sometimes congregate in groups of up to 1,400 spotted along the northeastern U.S.[34] Samples taken near feeding sharks contained 2.5 times as many Calanus helgolandicus individuals per cubic metre, which were also found to be 50% longer. Unlike the megamouth shark and whale shark, the basking shark relies only on the water it pushes through its gills by swimming; the megamouth shark and whale shark can suck or pump water through their gills.[6]

Reproduction

Basking sharks are ovoviviparous: the developing embryos first rely on a yolk sac, with no placental connection. Their seemingly useless teeth may play a role before birth in helping them feed on the mother's unfertilized ova (a behaviour known as oophagy).[35] In females, only the right ovary appears to function, and it is currently unknown why only one of the organs seems to function.

Gestation is thought to span over a year (perhaps two to three years), with a small, though unknown, number of young born fully developed at 1.5–2 m (4 ft 11 in–6 ft 7 in). Only one pregnant female is known to have been caught; she was carrying six unborn young.[36] Mating is thought to occur in early summer and birthing in late summer, following the female's movement into shallow waters.

The age of maturity is thought to be between the ages of six and 13 and at a length of 4.6–6 m (15–20 ft). Breeding frequency is thought to be two to four years.

The exact lifespan of the basking shark is unknown, but experts estimate to be about 50 years.[37][38]

Conservation

Aside from direct catches, by-catches in trawl nets have been one of several threats to basking sharks. In New Zealand, basking sharks had been abundant historically; however, after the mass by-catches recorded in 1990s and 2000s,[39] confirmations of the species became very scarce.[8] Management plans have been declared to promote effective conservations.[40][41] In June 2018 the Department of Conservation classified the basking shark as "Threatened - Nationally Vulnerable" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[42]

The eastern north Pacific Ocean population is a U.S. National Marine Fisheries Service species of concern, one of those species about which the U.S. Government's National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has some concerns regarding status and threats, but for which insufficient information is available to indicate a need to list the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA).[43]

The IUCN Red List indicates this as an endangered species.

The endangered aspect of this shark was publicised in 2005 with a postage stamp issued by Guernsey Post.

Importance to humans

Historically, the basking shark has been a staple of fisheries because of its slow swimming speed, placid nature, and previously abundant numbers. Commercially, it was put to many uses: the flesh for food and fishmeal, the hide for leather, and its large liver (which has a high squalene content) for oil.[11] It is currently fished mainly for its fins (for shark fin soup). Parts (such as cartilage) are also used in traditional Chinese medicine and as an aphrodisiac in Japan, further adding to demand.

As a result of rapidly declining numbers, the basking shark has been protected in some territorial waters and trade in its products is restricted in many countries under CITES. Among others, it is fully protected in the United Kingdom and the Atlantic and Mexican Gulf regions of the United States.[36] Since 2008, it has been illegal to fish for, or retain if accidentally caught, basking sharks in waters of the European Union.[36] It is partially protected in Norway and New Zealand, as targeted commercial fishing is illegal, but accidental bycatch can be used (in Norway any basking shark caught as bycatch and still alive must be released).[44][36][45] As of March 2010, it was also listed under Annex I of the CMS Migratory Sharks Memorandum of Understanding.[46]

Once considered a nuisance along the Canadian Pacific coast, basking sharks were the target of a government eradication programme from 1945 to 1970. As of 2008, efforts were under way to determine whether any sharks still lived in the area and monitor their potential recovery.[47]

It is tolerant of boats and divers approaching it, and may even circle divers, making it an important draw for dive tourism in areas where it is common.

Carcass misidentification

On several occasions, "globster" corpses initially identified by non-scientists as a sea serpents or plesiosaurs have later been identified as likely to be the decomposing carcasses of basking sharks, as in the Stronsay Beast and the Zuiyo-maru cases.[48]

See also

- List of prehistoric cartilaginous fish

- List of threatened sharks

- Shark liver oil

References

- Sepkoski, Jack (2002). "A compendium of fossil marine animal genera (Chondrichthyes entry)". Bulletins of American Paleontology. 364: 560. Archived from the original on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 9 January 2008.

- Rigby, C.L., Barreto, R., Carlson, J., Fernando, D., Fordham, S., Francis, M.P., Herman, K., Jabado, R.W., Liu, K.M., Marshall, A., Romanov, E. & Kyne, P.M. (2019). "Cetorhinus maximus". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2019: e.T4292A2988471.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Kruska, DC (1988). "Brain of the basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus)". Brain Behav. Evol. 32 (6): 353–63. doi:10.1159/000116562. PMID 3228691.

- Sims, DW; Southall, EJ; Richardson, AJ; Reid, PC; Metcalfe, JD (2003). "Seasonal movements and behaviour of basking sharks from archival tagging: no evidence of winter hibernation" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 248: 187–196. doi:10.3354/meps248187.

- Sims, DW (2008). Sieving a living: A review of the biology, ecology and conservation status of the plankton-feeding basking shark Cetorhinus maximus. Advances in Marine Biology. 54. pp. 171–220. doi:10.1016/S0065-2881(08)00003-5. ISBN 9780123743510. PMID 18929065.

- C. Knickle; L. Billingsley & K. DiVittorio. "Biological Profiles basking shark". Florida Museum of Natural History. Archived from the original on 21 August 2006. Retrieved 24 August 2006.

- Yarrell, William. (1836). A History of British Fishes. Volume II. John Van Voorst, London. p. 397.

- Basking shark. Department of Conservation. govt.nz

- Skomal, Gregory B.; Zeeman, Stephen I.; Chisholm, John H.; Summers, Erin L.; Walsh, Harvey J.; McMahon, Kelton W.; Thorrold, Simon R. (2009). "Transequatorial Migrations by Basking Sharks in the Western Atlantic Ocean". Current Biology. 19 (12): 1019–1022. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.04.019. PMID 19427211.

- Sims, DW; Southall, EJ; Tarling, GA; Metcalfe, JD (2005). "Habitat-specific normal and reverse diel vertical migration in the plankton-feeding basking shark". Journal of Animal Ecology. 74 (4): 755–761. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2656.2005.00971.x.

- Compagno, Leonard J. V. (1984). "CETORHINIDAE – Basking sharks" (PDF). Sharks of the World: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

- "Sharks in the Bay of Fundy, New Brunswick". Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- McClain CR, Balk MA, Benfield MC, Branch TA, Chen C, Cosgrove J, Dove ADM, Gaskins LC, Helm RR, Hochberg FG, Lee FB, Marshall A, McMurray SE, Schanche C, Stone SN, Thaler AD. 2015. Sizing ocean giants: patterns of intraspecific size variation in marine megafauna. PeerJ 3:e715 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.715

- Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. p. 256. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- Basking shark Cetorhinus maximus in Henry B. Bigelow, William C. Schroeder, Fishes of the Gulf of Maine, 1953, p. 28.

- "Basking Shark". San Francisco State University. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- "Basking shark". redorbit.com. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- Sims, DW; Southall, EJ; Richardson, AJ; Reid, PC; Metcalfe, JD (2003). "Seasonal movements and behaviour of basking sharks from archival tagging: no evidence of winter hibernation" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 248: 187–196. doi:10.3354/meps248187.

- Shepard, ELC; Ahmed, MZ; Southall, EJ; Witt, MJ; Metcalfe, JD; Sims, DW (2006). "Diel and tidal rhythms in diving behaviour of pelagic sharks identified by signal processing of archival tagging data". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 328: 205–213. doi:10.3354/meps328205.

- Sims, DW (2000). "Filter-feeding and cruising swimming speeds of basking sharks compared with optimal models: they filter-feed slower than predicted for their size". Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology. 249 (1): 65–76. doi:10.1016/s0022-0981(00)00183-0. PMID 10817828.

- Pelagic Shark Research Foundation. "PSRF Shark Image Library". PSRF. Retrieved 1 June 2006.

- Sims, DW; Quayle, VA (1998). "Selective foraging behaviour of basking sharks on zooplankton in a small-scale front". Nature. 393 (6684): 460–464. doi:10.1038/30959.

- Sims, DW; Southall, EJ; Richardson, AJ; Reid, PC; Metcalfe, JD (2003). "Seasonal movements and behaviour of basking sharks from archival tagging: no evidence of winter hibernation" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 248: 187–196. doi:10.3354/meps248187.

- Sims, DW (1999). "Threshold foraging behaviour of basking sharks on zooplankton: life on an energetic knife-edge?". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 266 (1427): 1437–1443. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0798. PMC 1690094.

- "Giant Shark Mystery Solved: Unexpected Hideout Found". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Howard, Brian Clark (23 June 2015). "Rare, Huge Basking Shark Caught Off Australia". National Geographic.

- "Rare, giant basking shark caught off Australian coast". CNN. 23 June 2015.

- "Rare 3500kg basking shark caught is donated to science". The Australian. 23 June 2015.

- Osborne, Hannah (23 June 2015). "Australia: Rare 6.3m Basking shark donated to science instead of being sold for its fins". International Business Times.

- On the presence of basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) in the Mediterranean Sea

- Cuma. 2009. Çanakkale’de 10 metrelik köpekbalığı!. Retrieved on September 04, 2017

- Sims, DW; Southall, EJ; Quayle, VA; Fox, AM (2000). "Annual social behaviour of basking sharks associated with coastal front areas". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 267 (1455): 1897–1904. doi:10.1098/rspb.2000.1227. PMC 1690754. PMID 11052542.

- Sims, DW; Merrett, DA (1997). "Determination of zooplankton characteristics in the presence of surface feeding basking sharks Cetorhinus maximus" (PDF). Marine Ecology Progress Series. 158: 297–302. doi:10.3354/meps158297.

- "Swarms of Huge Sharks Discovered, Baffling Experts". 12 April 2018.

- "Martin, R. Aidan. "Biology of the Basking Shark(Cetorhinus maximus)". ReefQuest Centre for Shark Research. Archived from the original on 28 May 2008. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- "Basking Shark Factsheet". The Shark Trust. Archived from the original on 17 February 2013. Retrieved 7 July 2006.

- Archipelagos Wildlife Library. "Basking Shark ( Cetorhinus maximus )". Archipelagos Wildlife Library. Archived from the original on 22 January 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Born Free Foundation. "Basking Shark Facts". Born Free Foundation. Archived from the original on 19 February 2013. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- Francis, M. P. & Smith, M. H. (2010). "Basking shark (Cetorhinus maximus) bycatch in New Zealand fisheries, 1994–95 to 2007–08". New Zealand Aquatic Environment and Biodiversity Report No. 49.

- MacFarlane, Trudy (18 June 2010) Submission on Management Options for Basking Sharks Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Ministry of Fisheries (New Zealand)

- Management Options for Basking Sharks to Give Effect to New Zealand's International Obligations. Ministry of Fisheries (New Zealand)

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 9. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.

- "Proactive Conservation Program: Species of Concern". noaa.gov. 5 May 2017.

- Fowler, S.L. (2005). "Cetorhinus maximus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2005: e.T4292A10763893. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2005.RLTS.T4292A10763893.en.

- "Fishing (Reporting) Regulations 2001, Schedule 3, Part 2C Protected Fish Species". NZ Government.

- "MEMORANDUM OF UNDERSTANDING ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SHARKS" (PDF). cms.int.

- Colonist, Times (21 August 2008). "B.C. scientists hunt for elusive shark". Canada.com. Archived from the original on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Kuban, Glen (May 1997). "Sea-monster or Shark?: An Analysis of a Supposed Plesiosaur Carcass Netted in 1977". Reports of the National Center for Science Education. 17 (3): 16–28.

- General references

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2005). "Cetorhinus maximus" in FishBase. 10 2005 version.

- "Cetorhinus maximus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 23 January 2006.

- David A Ebert, Sharks, Rays and Chimaeras of California, ISBN 0-520-23484-7

- Basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus at marinebio.org

- Marine Conservation Society Basking shark page

- FAO Figis Species Fact Sheet for basking shark

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cetorhinus maximus. |

- Basking shark, Cetorhinus maximus at marinebio.org

- Irish Basking Shark Project

- BBC Wildlife Finder – video news and news from the BBC archive

- ARKive entry on the Basking Shark

- Basking Shark Profile and Photos

- Fisheries & Oceans Canada – Basking sharks on the west coast of Canada

- Basking Sharks in the Isle of Man

- Photos of Basking shark on Sealife Collection

- Basking sharks featured on RNZ Critter of the Week, 24 Jan 2020