Concert of Europe

The Concert of Europe represented the European balance of power in two phases, the first from 1815 to the early 1860s, and the second from the early 1880s to 1914.

| 1815 to 1848 – 1871 to 1914 | |

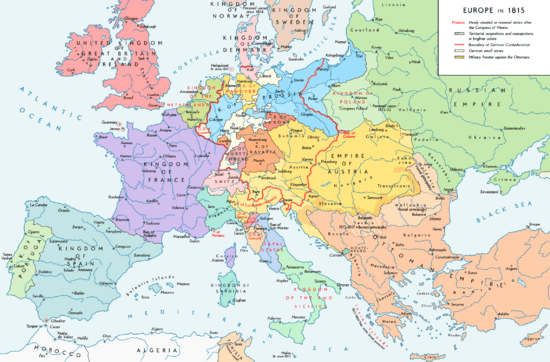

The national boundaries within Europe as set by the Congress of Vienna, 1815 | |

| Including | |

|---|---|

| Preceded by | Napoleonic era |

| Followed by | World War I |

The first phase of the Concert of Europe, known as the Congress System or the Vienna System after the Congress of Vienna (1814–15), was dominated by the five Great Powers of Europe: Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, and Great Britain. The more conservative members of the Concert of Europe, who were also members of the Holy Alliance, used this system to oppose revolutionary movements, weaken the forces of nationalism, and uphold the balance of power.

With the Revolutions of 1848 the Vienna system collapsed and, although the republican rebellions were checked, an age of nationalism began and culminated in the unifications of Italy (by Sardinia) and Germany (by Prussia) in 1871. The German chancellor Otto von Bismarck re-created the Concert of Europe to avoid future conflicts escalating into new wars. The revitalized concert included Austria, France, Italy, Russia, and Britain, with Germany as the main continental power militarily and economically. The Congress of Berlin and the Conference of Berlin promoted the solidification of power in the respective controlled regions as well as imperialism. Ultimately, the Concert of Europe split itself into the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente, which eventually became the principle groups of belligerents at the start of World War I in 1914, which ended the Congress system for good.[1]

Overview

The Concert of Europe describes the geopolitical world order centered around Europe from 1814–1914, revolving around the new Congress System – which is also referred to as the Vienna System. The Concert of Europe is typically explained in two distinct phases: the first from 1814 to the early 1860s, and the second from the 1880s to 1914. The final failure of the Concert of Europe in 1914 culminated in the First World War and was driven by various factors including rival alliances and the rise of nationalism. Remnants of this Congress-centered ideology (the Vienna System) can be seen in the following League of Nations and today's United Nations, all their own distinct examples of attempts at international cooperation and diplomacy.

The Concert of Europe was founded by the powers of Austria, Prussia, Russia and the Great Britain, which were the members of the Quadruple Alliance that defeated Napoleon. In time, France was established as a fifth member of the Concert which marked the formation of the Quintuple Alliance, following the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy. The Ottoman Empire was later admitted to the Concert of Europe in 1856 with the Treaty of Paris.[2]

At first, the leading personalities of the system were British foreign secretary Lord Castlereagh, Austrian chancellor and foreign minister Klemens von Metternich, and Emperor Alexander I of Russia. Charles Maurice de Talleyrand-Périgord of France was largely responsible for quickly returning the country to its place alongside the other major powers in international diplomacy.

The Concert of Europe is sometimes known as the Age of Metternich, due to the influence of the Austrian chancellor's conservatism and the dominance of Austria within the German Confederation, or as the European Restoration, because of the reactionary efforts of the Congress of Vienna to restore Europe to its state before the French Revolution. It is known in German as the Pentarchie (pentarchy) and in Russian as the Vienna System (Венская система, Venskaya sistema).

History

The idea of a European federation had been already raised by figures such as Gottfried Leibniz[3] and Lord Grenville.[4] The Concert of Europe, as developed by Metternich, drew upon their ideas and the notion of a balance of power in international relations, so that the ambitions of each Great Power would be restrained by the others:

The Concert of Europe, as it began to be called at the time, had ... a reality in international law, which derived from the final Act of the Vienna Congress, which stipulated that the boundaries established in 1815 could not be altered without the consent of its eight signatories.[5]

French Revolution

From the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1792 to the exile of Napoleon to Saint Helena in 1815, Europe had been almost constantly at war. During this time, the military conquests of France had resulted in the spread of liberalism throughout much of the continent, resulting in many states adopting the Napoleonic Code. Largely as a reaction to the radicalism of the French Revolution,[6] most of the victorious powers of the Napoleonic Wars resolved to suppress liberalist and nationalist movements, and revert largely to the status quo of Europe prior to 1789.[7]

First phase

The first phase of the Concert of Europe is typically described as beginning in 1814 with the Congress of Vienna, and ending in the early 1860s with the Prussian and Austrian invasion of Denmark.[8] This first phase included numerous congresses, including the Congress of Paris in 1856 which some scholars argue represented the apex of the Concert of Europe in its ending of the Crimean War.[8]

Holy Alliance

The Kingdom of Prussia, and the Austrian and Russian empires, formed the Holy Alliance on 26 September 1815, with the expressed intent of preserving Christian social values and traditional monarchism.[9] Every member of the anti-Napoleonic coalition promptly joined the Alliance, except for Great Britain, a constitutional monarchy with a more liberal political philosophy. The great powers were now in a system of meeting wherever a problem arose. Britain and France did not send their representatives because they opposed the idea of intervention.

Quadruple Alliance

Britain did however ratify the Quadruple Alliance, signed on 20 November 1815, the same day as the Second Treaty of Paris was signed, which later became the Quintuple Alliance when France joined in 1818. It was also signed by the same three powers that had formed the Holy Alliance.[10]

Differences between the Holy Alliance and the Quadruple Alliance

There has been much debate between historians as to which treaty was more influential in the development of international relations in Europe in the two decades following the end of the Napoleonic Wars. In the opinion of historian Tim Chapman the differences are somewhat academic, as the powers were not bound by the terms of the treaties and many of them intentionally broke the terms if it suited them.[11]

The Holy Alliance was the brainchild of Tsar Alexander I. It gained a lot of support because most European monarchs did not wish to offend the Tsar by refusing to sign it, and as it bound monarchs personally rather than their governments, it was easy to ignore once signed. Only three notable princes did not sign: Pope Pius VII (it was not Catholic enough), Sultan Mahmud II of the Ottoman Empire, and the British Prince Regent because his government did not wish to pledge itself to the policing of continental Europe. In the opinion of Lord Castlereagh, the British foreign secretary at the time of its inception, the Holy Alliance was "a piece of sublime mysticism and nonsense".[11] Although it did not fit comfortably within the complex, sophisticated and cynical web of power politics that epitomised diplomacy of the post-Napoleonic era, its influence was more long lasting than its contemporary critics expected and was revived in the 1820s as a tool of repression when the terms of the Quintuple Alliance were not seen to fit the purposes of some of the Great Powers of Europe.[12]

The Quadruple Alliance, by contrast, was a standard treaty, and the four Great Powers did not invite any of their allies to sign it. The primary objective was to bind the signatories to support the terms of the Second Treaty of Paris for 20 years. It included a provision for the High Contracting Parties to "renew their meeting at fixed periods...for the purpose of consulting on their common interests" which were the "prosperity of the Nations, and the maintenance of peace in Europe".[13] A problem with the wording of Article VI of the treaty is that it did not specify what these "fixed periods" were to be and there were no provisions in the treaty for a permanent commission to arrange and organise the conferences. This meant that the first conference in 1818 dealt with remaining issues of the French wars, but after that instead of meeting at "fixed periods" the meetings were arranged on an ad hoc basis, to address specific threats, such as those posed by revolutions, for which the treaty was not drafted.[14]

Quintuple Alliance

The Quintuple Alliance formed in October 1818 when France joined the Quadruple Alliance, with the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle.[15] France was the 5th member of this alliance, which now comprised France, Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain.[15]

Second phase

The second phase of the Concert of Europe is typically described as beginning in the early 1880s with another attempt at alliances driven largely by German Chancellor Bismarck, and ending in 1914 which resulted in the outbreak of World War I.[8] The creation of the Triple Alliance (which consisted of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy) and the rival Triple Entente (which consisted of France, Russia, and Great Britain) occurred during the end of the second phase of the Concert of Europe.[16] It is these two alliances which played major factors in pitting European powers against each other, contributing to Balkan instability in the former Yugoslavia, and the outbreak of the first World War.[17]

Congresses

1814 Congress of Vienna

The Concert of Europe began with the 1814-1815 Congress of Vienna, which was designed to bring together the "major powers" of the time in order to stabilize the geopolitics of Europe after the defeat of Napoleon in 1813–1814, and contain France's power after the war following the French Revolution.[18] The Congress of Vienna took place from November 1814 to June 1815 in Vienna, Austria, and brought together representatives from over 200 European polities.[18] The Congress of Vienna created a new international world order which was based on two main ideologies: restoring and safeguarding power balancing in Europe; and collective responsibility for peace and stability in Europe among the "great powers".[18]

1818 Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle

The 1818 Congress of Aix-la-Chapelle formed the Quintuple Alliance by adding France to the Quadruple Alliance, which had comprised Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia.[19] The ability for this to happen was given by Article V of the Quadruple Alliance, and resulted in ending the occupation of France.[20]

1820 Congress of Troppau

The 1820 Congress of Troppau was held in Troppau, Austria by the Great Powers of the Quintuple Alliance (Russia, Prussia, Austria, France, and Great Britain) to discuss and put down the Napoleonic Revolution in Naples that caused King Ferdinand I to agree to a constitutional monarchy – which was seen by Prussia and Austria as a threat of liberalism.[21] Other powers present at this Congress include Spain, Naples, and Sicily.[19] At this Congress, the Troppau Protocol was signed, which stated that if States which have undergone a change of government due to a revolution threaten other States, then they are ipso facto no longer members of the European Alliance if their exclusion will help to maintain legal order and stability. Furthermore, the Powers of the Alliance would also be bound to peacefully or by means of war bring the excluded State back into the Alliance.[19]

1821 Congress of Laibach

The 1821 Congress of Laibach took place in Laibach (now Ljubljana, Slovenia), between the powers of the Holy Alliance (Russia, Prussia, and Austria) in order to discuss the Austrian invasion and occupation of Naples in order to put down the Napoleonic Revolution.[22] Other powers present at this Congress include Naples, Sicily, Great Britain, and France.[19] The Congress of Laibach represented beginning tensions within the Concert of Europe, between the Eastern powers of Russia, Prussia, and Austria, versus the Western powers of Britain and France.[22]

1822 Congress of Verona

The 1822 Congress of Verona took place in Verona, Italy, between the powers of the Quintuple Alliance (Russia, Prussia, Austria, France, and Great Britain), along with Spain, Sicily, and Naples.[19] This Congress dealt with the question of Spanish revolution of 1820; Russia, Prussia, and Austria agreed to support France's planned intervention in Spain, while Great Britain opposed it.[23] This Congress also looked to deal with the Greek revolution against Turkey, but due to the opposition of Great Britain and Austria to Russian intervention in the Balkans, the Congress of Verona did not end up working on this issue.[23]

1830 London Conference

The 1830–1832 London Conference took place in London, Great Britain, between the powers of Great Britain, France, Prussia, Russia, Austria, Belgium, and the Netherlands.[19] This Conference dealt with the question of the Belgian–Dutch conflict, which was caused by the 1830 Belgian Revolution where Belgium separated from the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Austria, Prussia, and Russia saw Belgium's separation as an event that could negatively impact that Congress system, and worked to convince Belgium to return to the Kingdom of the Netherlands. On the other hand, Great Britain and France both supported Belgium's revolution, and were able to achieve recognition of Belgium from the Conference party members.[24]

1856 Congress of Paris

1878 Congress of Berlin

Decline

First phase

The fall of the first phase of the Concert of Europe can be attributed largely to the failure of a ceasefire in 1864 over the issue of Prussia's and Austria's invasion of Denmark in the Second Schleswig War.[25] Austria and Prussia both opposed negotiation settlement attempts, driving a wedge in the geopolitics of the Concert of Europe.[26] While various Congresses and Conferences took place between the early 1860s when the first phase fell, and the early 1880s when the second phase began, the cooperative nature of the Concert was significantly less present during this time of conflict.

Second phase

The fall of the second phase of the Concert of Europe can be attributed largely to the rival alliance systems – the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy) and the Triple Entente (France, Russia, and Great Britain) – which formed a rift in the European States.[26] These rival alliances threatened the underlying nature of the Concert, which relied on ad hoc alliances to respond to a given situation.[26] The crisis of July 1914 – the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo which lit the fuse on Balkan tensions[27] – catalyzed the collapse of the Concert of Europe for good, and marked the start of the first World War.

Role of nationalism

Nationalism played a role in the fall of both the first and second phases of the Concert of Europe, and was generally on the rise around the world before the start of the first World War; nationalism is seen by some scholars as a driving factor in the creation of the first World War. Particularly with the fall of the first phase, the rise of nationalism was in almost direct opposition to the core cooperative functions of the Concert, and resulted in States who were no longer well constrained by the Congress system.[26] The outbreak of conflict - namely in the Balkans after the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand - highlighted the final failure of the Concert of Europe, in that it was no longer able to constrain State national interests in order to maintain a cooperative international front.

See also

References

- "U.S. Resident Officers Conference". 1950.

- "Treaty of Paris of 1856" (PDF). Economic Cooperation Federation. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- Loemker, Leroy (1969) [1956]. Leibniz: Philosophical Papers and Letters. Reidel. p. 58, fn 9.

- Sherwig, John M. (September 1962). "Lord Grenville's Plan for a Concert of Europe, 1797–99". The Journal of Modern History. 34 (3): 284–93. doi:10.1086/239117.

- Soutou, Georges-Henri (November 2000). "Was There a European Order in the Twentieth Century? From the Concert of Europe to the End of the Cold War". Contemporary European History. Theme Issue: Reflections on the Twentieth Century. 9 (3): 330.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Soutou 2000, p. 329.

- Soutou 2000, p. 330.

- "Concert of Europe (The) | EHNE". ehne.fr. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

-

|year= / |date= mismatch(help) - Chapman, Tim (2006). The Congress of Vienna 1814–1815. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 978-1134680504.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Chapman 2006, p. 60.

- Chapman 2006, p. 61.

- Chapman 2006, p. 62.

- Chapman 2006, pp. 61–62.

- Lascurettes, Kyle (2017). "The Concert of Europe and Great-Power Governance Today" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- "The Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente - 1890-1905". www.lermuseum.org. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- "The Balkans and the outbreak of war | Century Ireland". www.rte.ie. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- "The Congress of Vienna (1814–1815)". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- Lascurettes, Kyle (2017). "The Concert of Europe and Great-Power Governance Today" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved October 17, 2019.

- "The Congress of Aachen [Aix-la-Chapelle] (1818) and the Completion of the Vienna System". Oxford Public International Law. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- "Congress of Troppau (1820)". erc-secure-db. Utrecht University. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- "Congress of Laibach | European history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2019-10-21.

- "History of The Concert of Europe (1815-22)". History Discussion - Discuss Anything About History. 2014-03-06. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- "London Conference of 1830–31". TheFreeDictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- "The German-Danish war (1864) - ICRC". www.icrc.org. 1998-04-06. Retrieved 2019-10-23.

- "Concert of Europe (The) | EHNE". ehne.fr. Retrieved 2019-10-17.

- "July Crisis 1914". International Encyclopedia of the First World War (WW1). Retrieved 2019-10-25.

Further reading

- Bridge, Roy (1979). "Allied Diplomacy in Peacetime: The Failure of the Congress 'System,' 1815–23" in Alan Sked, ed., Europe's Balance of Power, 1815–1848. pp. 34–53.

- Ghervas, Stella (2008). Réinventer la tradition. Alexandre Stourdza et l'Europe de la Sainte-Alliance. Paris: Honoré Champion. ISBN 978-2-7453-1669-1.

- Jarrett, Mark (2013). The Congress of Vienna and its Legacy: War and Great Power Diplomacy after Napoleon. London: I.B. Tauris & Company, Ltd. ISBN 978-1780761169.

- Laven, David, and Lucy Riall, eds. Napoleon's Legacy: Problems of Government in Restoration Europe (Berg, 2000).

- Lyons, Martin. Post-Revolutionary Europe, 1815-1856 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2006).