John Bull

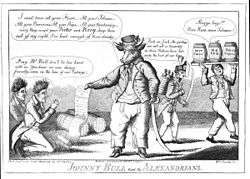

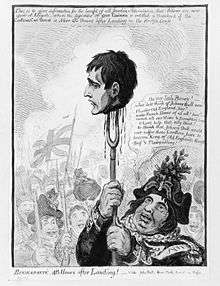

John Bull is a national personification of the United Kingdom in general and England in particular,[1] especially in political cartoons and similar graphic works. He is usually depicted as a stout, middle-aged, country-dwelling, jolly and matter-of-fact man.

Origin

John Bull originated as a satirical character created by Dr John Arbuthnot, a friend of Jonathan Swift and Alexander Pope. Bull first appeared in 1712 in Arbuthnot's pamphlet Law is a Bottomless Pit.[2] The same year Arbuthnot published a four-part political narrative The History of John Bull. In this satirical treatment of the War of the Spanish Succession John Bull brings a lawsuit against various figures intended to represent the kings of France (Louis Baboon) and Spain (Lord Strutt) as well as institutions both foreign and domestic.[3]

William Hogarth and other British writers made Bull, originally derided, "a heroic archetype of the freeborn Englishman."[2] Later, the figure of Bull was disseminated overseas by illustrators and writers such as American cartoonist Thomas Nast and Irish writer George Bernard Shaw, author of John Bull's Other Island.

Starting in the 1760s, Bull was portrayed as an Anglo-Saxon country dweller.[2] He was almost always depicted in a buff-coloured waistcoat and a simple frock coat (in the past Navy blue, but more recently with the Union Jack colours).[2] Britannia, or a lion, is sometimes used as an alternative in some editorial cartoons.

As a literary figure, John Bull is well-intentioned, frustrated, full of common sense, and entirely of native country stock. Unlike Uncle Sam later, he is not a figure of authority but rather a yeoman who prefers his small beer and domestic peace, possessed of neither patriarchal power nor heroic defiance. John Arbuthnot provided him with a sister named Peg (Scotland), and a traditional adversary in Louis Baboon (the House of Bourbon[4] in France). Peg continued in pictorial art beyond the 18th century, but the other figures associated with the original tableau dropped away. John Bull himself continued to frequently appear as a national symbol in posters and cartoons as late as World War I.

Depiction

Bull is usually depicted as a stout man in a tailcoat with light-coloured breeches and a top hat which, by its shallow crown, indicates its middle class identity. During the Georgian period his waistcoat is red and/or his tailcoat is royal blue which, together with his buff or white breeches, can thus refer to a greater or lesser extent to the "blue and buff" scheme;[2] this was used by supporters of Whig politics, which was part of what John Arbuthnot wished to deride when he created and designed the character. By the twentieth century, however, his waistcoat nearly always depicts a Union Flag,[2] and his coat is generally dark blue. (Otherwise, however, his clothing still echoes the fashions of the Regency period.) He also wears a low topper (sometimes called a John Bull topper) on his head and is often accompanied by a bulldog. John Bull has been used in a variety of different ad campaigns over the years, and is a common sight in British editorial cartoons of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Singer David Bowie wore a coat in the style of Bull.[2]

Washington Irving described him in his chapter entitled "John Bull" from The Sketch Book:

- "...[A] plain, downright, matter-of-fact fellow, with much less of poetry about him than rich prose. There is little of romance in his nature, but a vast deal of a strong natural feeling. He excels in humour more than in wit; is jolly rather than gay; melancholy rather than morose; can easily be moved to a sudden tear or surprised into a broad laugh; but he loathes sentiment and has no turn for light pleasantry. He is a boon companion, if you allow him to have his humour and to talk about himself; and he will stand by a friend in a quarrel with life and purse, however soundly he may be cudgelled."

The cartoon image of stolid, stocky, conservative and well-meaning John Bull, dressed like an English country squire, sometimes explicitly contrasted with the conventionalised scrawny, French revolutionary sans-culottes Jacobin, was developed from about 1790 by British satirical artists James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson and George Cruikshank. (An earlier national personification was Sir Roger de Coverley, from a 1711 edition of The Spectator.)

A more negative portrayal of John Bull occurred in the cartoons drawn by the Egyptian nationalist journalist Yaqub Sanu in his popular underground newspaper Abu-Naddara Zarqa in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.[5] Sanu's cartoons depicted John Bull as a coarse, ignorant drunken bully who pushed around ordinary Egyptians while stealing all the wealth of Egypt.[6] Much of Sanu's humor revolved around John Bull's alcoholism, his crass rudeness, his ignorance about practically everything except alcohol, and his inability to properly speak French (the language of the Egyptian elite), which he hilariously mangled unlike the Egyptian characters who spoke proper French.[7]

Increasingly through the early twentieth century, John Bull became seen as not particularly representative of "the common man," and during the First World War this function was largely taken over by the figure of Tommy Atkins.[8] According to Alison Light, during the interwar years the nation abandoned "formerly heroic...public rhetorics of national destiny" in favour of "an Englishness at once less imperial and more inward-looking, more domestic and more private".[9] Consequently, John Bull was replaced by Sidney Strube's suburban Little Man as the personification of the nation.[10] Some saw John Bull's replacement by the Little Man as symbolic of Britain's post-First World War decline; W. H. Auden's 1937 poem "Letter to Lord Byron" favourably contrasted John Bull to the Little Man.[11] Auden wrote:

- Ask the cartoonist first, for he knows best.

- Where is the John Bull of the good old days,

- The swaggering bully with the clumsy jest?

- His meaty neck has long been laid to rest,

- His acres of self-confidence for sale;

- He passed away at Ypres and Passchendaele.[12]

John Bull's surname is also reminiscent of the alleged fondness of the English for beef, reflected in the French nickname for English people, les rosbifs, which translates as "the 'Roast Beefs.'" It is also reminiscent of the animal, and for that reason Bull is portrayed as "virile, strong, and stubborn," like a bull.[2]

A typical John Bull Englishman is referenced in Margaret Fuller's Summer on the Lakes, in 1843 in Chapter 2: "Murray's travels I read, and was charmed by their accuracy and clear broad tone. He is the only Englishman that seems to have traversed these regions, as man, simply, not as John Bull."

In 1966, The Times, criticising the Unionist government of Northern Ireland, branded the region "John Bull's Political Slum."

In fiction

In Jules Verne's novel The Mysterious Island a character calls some unseen adversaries "sons of John Bull!", which is explained with: "When Pencroft, being a Yankee, treated any one to the epithet of 'son of John Bull,' he considered he had reached the last limits of insult."[13] In another of Verne's novels, Around the World in Eighty Days, an American colonel refers to the English protagonist as "a son of John Bull."[14]

Some John Bull imagery appears in the first volume of The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen by Alan Moore and Kevin O'Neill. John Bull is visible in the illustration accompanying the foreword, on a matchbox on the comic's first page and in person at the bottom of the final panel.

In the Japanese anime Hellsing Ultimate, Alucard refers to Walter, the Hellsing family butler, as "John Bull" on a few occasions, often in mockery.

In the Japanese anime Youjo Senki, the main character Tanya Degurechaff references soldiers from the Allied Kingdom (a fictitious analogue to the United Kingdom) as John Bulls.

In the Clint Eastwood film Unforgiven, a character by the nickname of "English Bob" (played by Richard Harris) is derisively called "John Bull".

See also

- List of national symbols of the United Kingdom, the Channel Islands and the Isle of Man

- Terminology of the British Isles

- John Bull's Other Island

- Sawney

- Brother Jonathan

- Uncle Sam

- Marianne

- Britannia, the female personification of Britain.

- William Ball, "the Shropshire Giant", a nineteenth century giant who displayed himself in public as 'John Bull'.

References

- Taylor, Miles (2004). "Bull, John (supp. fl. 1712–)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/68195.

- "AngloMania: Tradition and Transgression in British Fashion," Metropolitan Museum of Art (2006), exhibition brochure, p. 2.

- Adrian Teal, "Georgian John Bull", pages 30–31 "History Today January 2014"

- "The view from England". The Fitzwilliam Museum. 3 July 2007.

- Fahamy, Ziad "Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya'qub Sannu'" pp. 170-183 from Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 28, Number 1, 2008 pp. 173-175.

- Fahamy, Ziad "Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya'qub Sannu'" pp. 170-183 from Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 28, Number 1, 2008 pp. 173-175.

- Fahamy, Ziad "Francophone Egyptian Nationalists, Anti-British Discourse, and European Public Opinion, 1885-1910: The Case of Mustafa Kamil and Ya'qub Sannu'" pp. 170-183 from Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, Volume 28, Number 1, 2008 pp. 174-175.

- Carter, Philip. "Myth, legend, and mystery in the Oxford DNB". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press.

- Todd Kuchta, Semi-Detached Empire: Suburbia and the Colonization of Britain, 1880 to the Present (University of Virginia Press, 2010), p. 173.

- Rod Brookes, '‘Everything in the Garden Is Lovely’: The Representation of National Identity in Sidney Strube's "Daily Express" Cartoons in the 1930s', Oxford Art Journal, Vol. 13, No. 2 (1990), p. 32.

- Kuchta, p. 174.

- Norman Page, The Thirties (London: Macmillan, 1990), p. 25.

- Verne, Jules (1875). The Mysterious Island.

son of john bull the mysterious island.

- 1828-1905., Verne, Jules (1996). Around the world in eighty days. New York: Viking. ISBN 9780140367119. OCLC 34726054.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

External links

![]()