Homo antecessor

Homo antecessor is an archaic human species of the Lower Paleolithic, known to have been present in Western Europe (Spain, England and France) between about 1.2 million and 0.8 million years ago (Mya). It was described in 1997 by Eudald Carbonell, Juan Luis Arsuaga and José María Bermúdez de Castro, who based on its "unique mix of modern and primitive traits" classified it as a previously unknown archaic human species.[1]

| Homo antecessor | |

|---|---|

| |

| The "Boy of Gran Dolina" fossils ATD6-15 (frontal bone) and ATD6-69 (maxilla) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | Homininae |

| Tribe: | Hominini |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. antecessor |

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo antecessor Bermúdez de Castro et al., 1997 | |

The fossils associated with Homo antecessor represent the oldest direct fossil record of the presence of Homo in Europe.[2] The species name antecessor proposed in 1997 is a Latin word meaning "predecessor", or "vanguard, scout, pioneer". Authors who do not accept H. antecessor as a separate species consider the fossils in question an early form of H. heidelbergensis or as a European variety of H. erectus.

Taxonomy

Research history

H. antecessor was discovered in 1991 in the Gran Dolina site of the Sierra de Atapuerca region of northern Spain by Spanish palaeoanthropologists José María Bermúdez de Castro, Eudald Carbonell, and Juan Luis Arsuaga. These remains were deposited in the sixth level (TD6) dating to about 780,000 years ago, making them the oldest European human fossils.[3] Stone tools indicate hominin activity in Europe as early as 1.6 mya in Eastern Europe and Spain.[4] The sediment of Gran Dolina was dated at 900,000 years old in 2014.[5] More than 80 bone fragments from six individuals were uncovered in 1994 and 1995. The site also had included approximately 200 stone tools and 300 animal bones. Stone tools including a stone carved knife were found along with the ancient hominin remains. All these remains were dated at least 900,000 years old.[3] The best preserved specimens are ATD6-15 and ATD6-69, a frontal bone and a maxilla (upper jawbone) of a 10 year old boy, dubbed the "Gran Dolina Boy" (el chico de la Gran Dolina),[6] dating to 859–782,000 years ago.[7]

In 2007, a molar dating to 1.2–1.1 million years ago was recovered from the nearby Sima del Elefante site. It belonged to a 20–25 year old individual. In 2008, an additional mandible fragment, stone flakes, and evidence of butchery were discovered.[8] Until 2013 with the discovery of the 1.4 Ma infant tooth from Barranco León, Orce, Spain, these were the oldest human fossils known from Europe.[9]

Evidence of early human presence in England and France has later been tentatively associated with H. antecessor purely on chronological grounds and not based on anatomical evidence. Fifty footprints dating to between 1.2 million and 800,000 years ago were discovered in Happisburgh, England. They were possibly made by an H. antecessor group.[10]

Classification

H. antecessor has been proposed as a chronospecies intermediate between H. erectus (c. 1.9–1.4 Mya) and H. heidelbergensis (c. 0.8–0.3 Mya). While H. heidelbergensis is widely accepted as the immediate predecessor of H. neanderthalensis, and possibly H. sapiens, the derivation of H. heidelbergensis from H. antecessor is debatable. H. antecessor's discoverers suggested H. antecessor as a derivation of African H. erectus (H. ergaster) which would have migrated to the Iberian Peninsula at some point before 1.2 Mya, and developed into H. heidelbergensis by 0.8 Mya, and further into H. neanderthalensis after 0.3 Mya.[2][11][12]

In 2009, palaeoanthropologist Richard Klein stated he was skeptical that H. antecessor was ancestral to H. heidelbergensis, interpreting H. antecessor as a "failed attempt to colonize southern Europe".[13] The legitimacy of H. antecessor as a separate species has also been questioned because the fossil record is fragmentary, and especially as no complete skull has been found, with only fourteen fragments and lower jaw bones known.[2][14] Because of this, it is also proposed that H. antecessor was an early form of H. heidelbergensis, which would extend the range of H. heidelbergensis to 1.2–0.3 Mya.[15] A 2020 analysis by Welker et al. of ancient proteins collected from a tooth of an H. antecessor specimen indicated that H. antecessor belonged to a "sister lineage" related to the ancestor of modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans, but was not itself their direct ancestor, corroborating earlier opinions that H. heidelbergensis was not derived from H. antecessor.[16][17]

Physiology

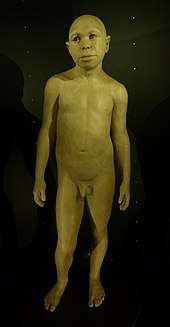

Based on the radial and clavicle lengths, the statures of 2 specimens were calculated to be 174.5 cm (5 ft 9 in) and 170.9 cm (5 ft 7 in). The body proportions of H. antecessor fall within the range of variation for modern humans, and upper limb proportions were likely more similar to those of modern humans than Neanderthals.[11]

The facial anatomy of the Boy of Gran Dolina appears very similar to that of modern humans, and it was thus suggested that this marked the beginning of modern human facial features. These features likely did not change so drastically with age. However, modern humanlike facial features may have evolved multiple times independently among different human lineages.[18]

Based on teeth eruption pattern, the researchers think that H. antecessor had the same development stages as H. sapiens, though probably at a faster pace. Other significant features demonstrated by the species are a protruding occipital bun, a low forehead, and a lack of a strong chin. Some of the remains are almost indistinguishable from the fossil attributable to the 1.5-million-year-old Turkana Boy, belonging to H. ergaster.

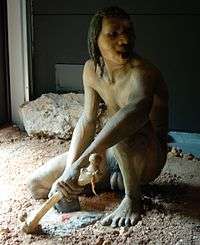

Behaviour

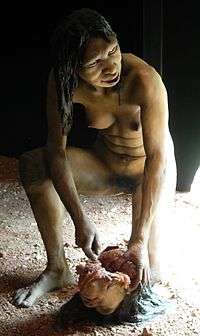

The large animal carcasses at Gran Dolina appear to have been carried to the site intact. This indicates that H. antecessor groups dispatched multi-member hunting parties who delayed eating immediately after a successful kill in order to share it with all group members after hauling it back, showing social cooperation, division of labour, and food sharing. A total of 16 species were recorded from Gran Dolina, including the bush-antlered deer, an extinct species of fallow deer, an extinct red deer, an extinct bison, a wild boar, the rhino Stephanorhinus etruscus, the Stenon zebra, a mammoth, the Mosbach wolf, the fox Vulpes praeglacialis, the Gran Dolina bear, the spotted hyena, and a lynx. The most common butchered remains are those of deer.[19] Also, adult and child H. antecessor specimens from Gran Dolina exhibit cut marks, crushing, burning, and other trauma indicative of cannibalism,[11] and are the second-most common remains bearing evidence of butchering.[19] It is unclear if cannibalism was practiced often (ritual cannibalism) or if this was an isolated incident in a dire situation (survival cannibalism).[20][11]

See also

- Out of Africa I

- Peopling of Europe

- Happisburgh footprints

- Homo heidelbergensis

- Ceprano Man

- Tautavel Man

References

- Bermudez de Castro, JM; Arsuaga, JL; Carbonell, E; Rosas, A; Martinez, I; Mosquera, M (1997). "A Hominid from the Lower Pleistocene of Atapuerca, Spain: Possible Ancestor to Neandertals and Modern Humans" (PDF). Science. 276 (5317): 1392–1395. doi:10.1126/science.276.5317.1392. PMID 9162001.

- Wayman, Erin (November 26, 2011). "Homo antecessor: Common Ancestor of Humans and Neanderthals?". Smithsonian. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- Parés, JM; Arnold, L; Duval, M; Demuro, M; Pérez-Gonzáleza, A; Bermúdez de Castro, JM; Carbonell, E; Arsuagac, JL (2013). "Reassessing the age of Atapuerca-TD6 (Spain): new paleomagnetic results" (PDF). Journal of Archaeological Science. 40 (12): 4586–4595. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2013.06.013.

- Moyano, I. T.; Barsky, D. (2011). "The archaic stone tool industry from Barranco León and Fuente Nueva 3, (Orce, Spain): Evidence of the earliest hominin presence in southern Europe". Quaternary International. 243 (1): 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.12.011.

- "Dating is refined for the Atapuerca site where Homo antecessor appeared". Science X Network. February 7, 2014. Retrieved December 10, 2015.

- Bermúdez de Castro, José M (2002). El chico de la Gran Dolina (PDF) (in Spanish).

- Falguères, Christophe; Bahain, J.; Yokoyama, Y.; Arsuaga, J.; Bermudez de Castro, J.; Carbonell, E.; Bischoff, J.; Dolo, J. (1999). "Earliest humans in Europe: the age of TD6 Gran Dolina, Atapuerca, Spain". Journal of Human Evolution. 37 (3–4): 343–352 [351]. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0326. PMID 10496991.

- Carbonell, Eudald (2008-03-27). "The first hominin of Europe" (PDF). Nature. 452 (7186): 465–469. doi:10.1038/nature06815. hdl:2027.42/62855. PMID 18368116.

- Toro-Moyano, I; Martínez-Navarro, B; Agustí, J; Souday, C; Bermúdez; de Castro, JM; Martinón-Torres, M; Fajardo, B; Duval, M; Falguères, C; Oms, O; Parés, JM; Anadón, P; Julià, R; García-Aguilar, JM; Moigne, AM; Espigares, MP; Ros-Montoya, S; Palmqvist, P (2013). "The oldest human fossil in Europe, from Orce (Spain)". J Hum Evol. 65 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.01.012. hdl:10261/84112. PMID 23481345.

- Ashton, N; Lewis, SG; De Groote, I; Duffy, SM; Bates, M; Bates, R; et al. (2014). "Hominin Footprints from Early Pleistocene Deposits at Happisburgh, UK". PLoS ONE. 9 (2): e88329. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088329. PMC 3917592. PMID 24516637.

- Carretero, JM; Lorenzo, C; Arsuaga, JL (October 1, 1999). "Axial and appendicular skeleton of Homo antecessor". J. Hum. Evol. 37 (3–4): 459–99. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0342. PMID 10496997.

- "... a speciation event could have occurred in Africa/Western Eurasia, originating a new Homo clade [...] Homo antecessor [...] could be a side branch of this clade placed at the westernmost region of the Eurasian continent".Bermúdez-de-Castro, José-María (May 23, 2015). "Homo antecessor: The state of the art eighteen years later". Quaternary International. 433: 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2015.03.049.

- Klein, Richard. 2009. "Hominin Disperals in the Old World" in The Human Past, ed. Chris Scarre, 2nd ed., p. 108.

- Sarmiento, Esteban E.; Sawyer, Gary J.; Mowbray, Kenneth; Milner, Richard; Deak, Viktor; Johanson, Donald C.; Tattersall, Ian (2007). The Last Human: A Guide to Twenty-two Species of Extinct Humans By Esteban E. Sarmiento, Gary J. Sawyer, Richard Milner, Viktor Deak, Ian Tattersall. ISBN 9780300100471.

- "Homo antecessor". Australian Museum. November 26, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2015.

- Scharping, Nathaniel (1 April 2020). "An Ancient Tooth Is Revealing More About Our Human Ancestors: Remains found in Spanish caves also have modern-like facial characteristics". Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- Welker, Frido; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Gutenbrunner, Petra; Mackie, Meaghan; Tiwary, Shivani; Rakownikow Jersie-Christensen, Rosa; Chiva, Cristina; Dickinson, Marc R.; Kuhlwilm, Martin; de Manuel, Marc; Gelabert, Pere; Martinón-Torres, María; Margvelashvili, Ann; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Carbonell, Eudald; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Penkman, Kirsty; Sabidó, Eduard; Cox, Jürgen; Olsen, Jesper V.; Lordkipanidze, David; Racimo, Fernando; Lalueza-Fox, Carles; Bermúdez de Castro, José María; Willerslev, Eske; Cappellini, Enrico (2020-04-01). "The dental proteome of Homo antecessor". Nature. 580 (7802): 235–238. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2153-8. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 32269345.

- Freidline, S. E.; Gunz, P.; et al. (2013). "Evaluating developmental shape changes in Homo antecessor subadult facial morphology". Journal of Human Evolution. 65 (4): 404–423. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2013.07.012.

- Saladié, P.; Huguet, R.; et al. (2011). "Carcass transport decisions in Homo antecessor subsistence strategies". Journal of Human Evolution. 61 (4): 425–446. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.05.012.

- Fernández-Jalvo, Y.; Díez, J. C.; Cáceres, I.; Rosell, J. (September 1999). "Human cannibalism in the Early Pleistocene of Europe (Gran Dolina, Sierra de Atapuerca, Burgos, Spain)". Journal of Human Evolution. 37 (34): 591–622. doi:10.1006/jhev.1999.0324. PMID 10497001.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Homo antecessor. |