Sahelanthropus

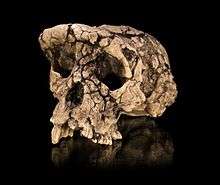

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an extinct species of the Homininae (African apes) dated to about 7 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch. The species, and its genus Sahelanthropus, was announced in 2002, based mainly on a partial cranium, nicknamed Toumaï, discovered in northern Chad.

| Sahelanthropus tchadensis "Toumaï" | |

|---|---|

| |

| Cast of a Sahelanthropus tchadensis skull (Toumaï) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Infraorder: | Simiiformes |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Subfamily: | incertae sedis |

| Genus: | †Sahelanthropus Brunet et al., 2002[1] |

| Species: | †S. tchadensis |

| Binomial name | |

| †Sahelanthropus tchadensis Brunet et al., 2002[1] | |

Sahelanthropus tchadensis lived close to the time of the chimpanzee–human divergence, and is likely an ancestor to Orrorin, a species of Homininae that lived about one million years later. It may have been ancestral to both humans and chimpanzees (which would place it in the tribe Hominini), or alternatively an early member of the tribe Gorillini.

Fossils

Existing fossils include a relatively small cranium, five pieces of jaw, and some teeth, making up a head that has a mixture of derived and primitive features. The braincase, being only 320 cm3 to 380 cm3 in volume, is similar to that of extant chimpanzees and is notably less than the approximate human volume of 1350 cm3.

The teeth, brow ridges, and facial structure differ markedly from those found in Homo sapiens. Cranial features show a flatter face, u-shaped dental arcade, small canines, an anterior foramen magnum, and heavy brow ridges. No postcranial remains have been recovered. The only known skull suffered a large amount of distortion during the time of fossilisation and discovery, as the cranium is dorsoventrally flattened, and the right side is depressed.[1]

Discovery and name

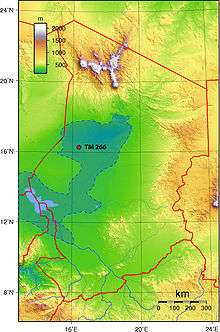

The fossils were discovered in the Djurab Desert of Chad by a team of four led by a Frenchman, Alain Beauvilain, and three Chadians, Adoum Mahamat, Djimdoumalbaye Ahounta, and Gongdibé Fanoné, members of the Mission paleoanthropologique Franco-tchadienne led by Michel Brunet.[2][3] All known material of Sahelanthropus was found between July 2001 and March 2002 at three sites in the Toros-Menalla formation, designated TM 266 (which yielded most of the material, including a cranium and a femur), TM 247 and TM 292. The discoverers claimed that S. tchadensis is the oldest-known human ancestor after the split of the human line from that of chimpanzees.[4]

The bones were found far from most previous hominin fossil finds, which are from Eastern and Southern Africa. However, an Australopithecus bahrelghazali mandible was found in Chad by Mamelbaye Tomalta, Najia and Alain Beauvilain, Michel Brunet and Aladji H. E. Moutaye as early as 1995.[5] With the sexual dimorphism known to have existed in early hominins, the difference between Ardipithecus and Sahelanthropus may not be large enough to warrant a separate species for the latter.[6]

Sahelanthropus ("Sahel man") was proposed as a new genus within Hominidae by Brunet et al. (2002). The species designation of tchadensis (reflecting the French spelling of the name of Chad) was proposed in the same publication, "[i]n recognition [of the fact] that all specimens were recovered in Chad."[1]

The nickname Toumaï given to the cranium reportedly is a given name in Dazaga, one of the Saharan languages spoken in the region, translating to "hope of life" and given to infants born just before the dry season. The nickname was suggested by the president of Chad, Idriss Déby. Déby explained that he chose the name in honour of one of his comrades-in-arms who was from the region, and who had been killed in the revolt against Hissène Habré.[7]

Bipedalism

Sahelanthropus tchadensis may have walked on two legs.[8] However, because no postcranial remains (i.e., bones below the skull) have been discovered, it is not known definitively whether Sahelanthropus was indeed bipedal, although claims for an anteriorly placed foramen magnum suggests that this may have been the case. Upon examination of the foramen magnum in the primary study, the lead author speculated that a bipedal gait "would not be unreasonable" based on basicranial morphology similar to more recent hominins.[1] Some palaeontologists have disputed this interpretation, stating that the basicranium, as well as dentition and facial features, do not represent adaptations unique to the hominin clade, nor indicative of bipedalism;[9] and stating that canine wear is similar to other Miocene apes.[1] Further, according to recent information, what might be a femur of a hominid was also discovered near the cranium—but which has not been published nor accounted for.[10]

In 2018, Roberto Macchiarelli, anthropologist at the University of Poitiers and the Museum of Natural History of Paris,[11] published his suspicion that Michel Brunet and his laboratory in Poitiers may have blocked information about a femur which may be Sahelanthropus found close to the skull.[12] The alleged motive for this suppression of information would be that the morphology of the femur might cast doubt on the bipedalism of Toumaï.[13][14][15][16]

Taxonomic classification

Sahelanthropus is described by Brunet as the earliest representative of the human lineage and this is endorsed by the Smithsonian Institution in its description of the species, which states that it has two key human characteristics, small canine teeth and walking upright on two legs. However, some researchers doubt whether Sahelanthropus is a hominin and argue that fossils in Ethiopia and Kenya are better candidates.[13][17]

The placement of this species as a human ancestor but not a chimpanzee ancestor, as suggested by the original 2002 publication by Brunet et al., the facial features of the Toumaï cranium bring into doubt the status of Australopithecus whose thickened brow ridges were reported to be similar to those of some later fossil hominins (notably Homo erectus), and where the brow ridge morphology of Sahelanthropus differs from that observed in all australopithecines, most fossil hominins and extant humans. Brahic (2012) reports on research concluding that the human–chimpanzee split is earlier than previously thought, with a possible range of 7 to 13 million years ago (with the more recent end of this range being favoured by most researchers), based on slower than previously thought changes between generations in human DNA. Tim D. White has taken this to imply that objections to the effect of Sahelanthropus being too old to belong to the Hominina (human) no longer carry weight.[18]

A further possibility is that Toumaï is not ancestral to either humans or chimpanzees at all, but rather an early representative of the Gorillini lineage. Brigitte Senut and Martin Pickford, the discoverers of Orrorin tugenensis, suggested that the features of S. tchadensis are consistent with a female proto-gorilla. Even if this claim is upheld the find would lose none of its significance, because at present, very few chimpanzee or gorilla ancestors have been found anywhere in Africa. Thus if S. tchadensis is an ancestral relative of the chimpanzees or gorillas, then it represents the earliest known member of their lineage. And S. tchadensis does indicate that the last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees is unlikely to closely resemble extant chimpanzees, as had been previously supposed by some paleontologists.[19][20]

Sediment isotope analysis of cosmogenic atoms in the fossil yielded an age of about 7 million years.[21] In this case, however, the fossils were found exposed in loose sand; co-discoverer Beauvilain cautions that such sediment can be easily moved by the wind, unlike packed earth, making the date of 7 million years less certain.[22] In fact, Toumaï may have been reburied in the recent past. Taphonomic analysis reveals the likelihood of one, perhaps two, burial(s). Two other hominid fossils (a left femur and a mandible) were in the same "grave" along with various mammal remains. The sediment surrounding the fossils might thus not be the material in which the bones were originally deposited, making it necessary to corroborate the fossil's age by some other means.[12] The fauna found at the site—namely the anthracothere Libycosaurus petrochii and the suid Nyanzachoerus syrticus—suggests an age of more than 6 million years, as these species were probably already extinct by that time.[23]

See also

- Ardipithecus

- Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor

- Human evolution

- Human timeline

- List of human evolution fossils (with images)

- Orrorin

References

- Brunet, M.; Guy, F.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (2002). "A new hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad, Central Africa". Nature. 418 (6894): 145–151. Bibcode:2002Natur.418..145B. doi:10.1038/nature00879. PMID 12110880.

- Beauvilain, Alain (5 October 2006). "Toumaï : "Histoire des Sciences et Histoire d'Hommes"". Tchad Actuel (in French). Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Toumaï, the Human Adventure". Chad, Cradle of Humanity?. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Brunet, M; Beauvilain, A; Coppens, Y; Heintz, E; Moutaye, A.H.E.; Pilbeam, D (1995). "The first australopithecine 2,500 kilometres west of the Rift Valley (Chad)" (PDF). Nature. 378 (6554): 273–275. Bibcode:1995Natur.378..273B. doi:10.1038/378273a0. PMID 7477344.

- Chad, cradle of humanity. Participants in sahara scientific mission

- Haile-Selassie, Yohannes; Suwa, Gen; White, Tim D. (2004). "Late Miocene Teeth from Middle Awash, Ethiopia, and Early Hominid Dental Evolution". Science. 303 (5663): 1503–1505. Bibcode:2004Sci...303.1503H. doi:10.1126/science.1092978. PMID 15001775.

- "Sahelanthropus tchadensis : Découverte de Toumaï, un "Tchadien" de 7 millions d'années". Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "What Does It Mean To Be Human? - Walking Upright". Smithsonian Institution. August 14, 2016. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- Wolpoff, Milford H.; Senut, Brigitte; Pickford, Martin; et al. (2002). "Palaeoanthropology (communication arising): Sahelanthropus or 'Sahelpithecus'?" (PDF). Nature. 419 (6907): 581–582. Bibcode:2002Natur.419..581W. doi:10.1038/419581a. hdl:2027.42/62951. PMID 12374970.

- Hawks, John (2009-07-03). "Sahelanthropus: The femur of Toumaï?". Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Anthropologie : Roberto Macchiarelli reçoit le prix " Fabio Frassetto " 2011" (in French). French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS). Retrieved 2020-01-01 – via Planet Techno Science.

- Beauvilain, A.; Watté, J.P. (2009). "Was Toumaï (Sahelanthropus Tchadensis) Buried?" (PDF). Anthropologie. 47 (1/2): 1–6. JSTOR 26292847.

- Callaway, Ewen (25 January 2018). "Femur findings remain a secret" (PDF). Nature. 553: 391–92. Bibcode:2018Natur.553..391C. doi:10.1038/d41586-018-00972-z. PMID 29368713.

- "Chronicle of Toumaï's femur rediscovery". Chad, Cradle of Humanity?. Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Constans, N (2018-01-23). "L'histoire du Fémur de Toumaï" [The history of Toumai's thighbone] (in French). Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- Hartenberger, J.L. (2018-12-13). "Toumaï aïe aïe aïe : triste histoire d'un fémur indigne" [sad story of an unworthy femur]. Le Dinoblog (in French). Retrieved 2020-01-01.

- "Sahelanthropus tchadensis". Smithsonian Institution. 24 August 2018.

- Catherine Brahic (24 Nov 2012). "Our True Dawn". New Scientist (2892): 34–7. ISSN 0262-4079., citing research by Augustine Kong (Decode Genetics, Reykjavik), David Reich (Harvard) and others

- Guy, F.; Lieberman, D.E.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (2005). "Morphological affinities of the Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Late Miocene hominid from Chad) cranium". PNAS. 102 (52): 18836–18841. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10218836G. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509564102. PMC 1323204. PMID 16380424.

- Wolpoff, M. H.; Hawks, J.; Senut, B.; et al. (2006). "An Ape or the Ape : Is the Toumaï Cranium TM 266 a Hominid?" (PDF). PaleoAnthropology. 2006: 36–50.

- Lebatard, A.-E.; Bourles, D. L.; Duringer, P.; et al. (2008). "Cosmogenic nuclide dating of Sahelanthropus tchadensis and Australopithecus bahrelghazali: Mio-Pliocene hominids from Chad". PNAS. 105 (9): 3226–3231. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.3226L. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708015105. PMC 2265126. PMID 18305174.

- Beauvilain, Alain (2008). "The contexts of discovery of Australopithecus bahrelghazali and of Sahelanthropus tchadensis (Toumaï) : unearthed, embedded in sandstone or surface collected?". South African Journal of Science. 104 (3): 165–168.

- Brunet, M.; Guy, F.; Pilbeam, D.; et al. (2005). "New material of the earliest hominid from the Upper Miocene of Chad" (PDF). Nature. 434 (7034): 752–755. Bibcode:2005Natur.434..752B. doi:10.1038/nature03392. PMID 15815627.

Further reading

- Beauvilain, Alain (2003). Toumaï: l'aventure humaine (in French). Table ronde. ISBN 2-7103-2592-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brunet, Michel (2006). D'Abel à Toumaï: Nomade, chercheur d'os (in French). Odile Jacob. ISBN 978-2-7381-1738-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbons, Ann (2006). The first human. Doubleday. ISBN 978-0385512268.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Reader, John (2011). Missing Links: In Search of Human Origins. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-927685-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sahelanthropus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Sahelanthropus |

- Fossil Hominids: Toumai

- National Geographic: Skull Fossil Opens Window Into Early Period of Human Origins

- New Findings Bolster Case for Ancient Human Ancestor

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis, Toumaï, Detailed composition of the Franco-Chadian palaeoanthropological Mission, the sahara scientific missions, the discovery’s context, controversy about the misplacement of a molar, the minimum number of individuals, the geology of the site, was Toumaï buried ? and research to date the skull,…

- Sahelanthropus news reporting by John Hawks

- S. tchadensis reconstruction

- Sahelanthropus tchadensis Origins – Exploring the Fossil Record – Bradshaw Foundation

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).