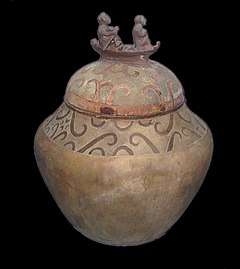

Manunggul Jar

The Manunggul Jar is a secondary burial jar excavated from a Neolithic burial site in the Manunggul cave of the Tabon Caves at Lipuun Point in Palawan. It dates from 890–710 B.C.[2] and the two prominent figures at the top handle of its cover represent the journey of the soul to the afterlife.

| Manunggul Jar | |

|---|---|

| |

| Year | 890-710 BCE |

| Type | Burial Jar |

| Dimensions | 66.5 cm (26.2 in); 51 cm diameter (20 in)[1] |

| Location | National Museum of Anthropology, Manila |

The Manunggul Jar is widely acknowledged to be one of the finest Philippine pre-colonial artworks ever produced and is considered a masterpiece of Philippine ceramics. It is listed as a national treasure and designated as item 64-MO-74[3] by the National Museum of the Philippines. It is now housed at the National Museum of Anthropology and is one of the most popular exhibits there. It is made from clay with some sand soil.

Discovery

The Manunggul Jar was found by Dr. Robert B. Fox and Miguel Antonio in 1962. It was found alongside the remains of Tabon Man. It was recovered by Dr. Fox in Chamber A of Manunggul Cave in Southwestern Palawan.[4][5] Manunggul Cave is one of the Tabon Caves in Lipuun Point. The Tabon Caves are known to be a site of jar burials with artefacts dating in a range from 2300 to 50 B.C. (4250-2000 BP).[4] Chamber A dates as a Late Neolithic burial site (890-710 BC).[4][6] Seventy-eight jars and earthenwares, including the Manunggul Jar, were discovered on the subsurface and surface of Chamber A. Each artefact varied in design and form but was evidently a type of funerary pottery.[7]

First excavation and response to discovery

The first ever excavation that discovered this burial jar was in the year 1964 by Dr. Robert Fox. During that time, he and his team were excavating the Tabon Cave Complex, specifically in the Lipuun Point. Fox’s excavation was most unusual in many ways.[8]

The inside of the jar contained human bones which were covered in red paint. Like Egyptian burial practices, the jar also had numerous bracelets.[9]

“... is perhaps unrivaled in Southeast Asia, the work of an artist and a master potter.” — These words were said by Robert Fox when asked as to how he would describe the jar’s origin, based from its appearance.[9]

Design of the Jar

The Manunggul Jar shows that the Filipinos' maritime culture is paramount that it reflected its ancestors' religious beliefs. Many epics around the Philippines would tell how souls go to the next life, aboard boats, pass through the rivers and seas. This belief is connected with the Austronesian belief of the anito. The fine lines and intricate designs of the Manunggul Jar reflect the artistry of early Filipinos. These designs are proof of the Filipinos' common heritage from the Austronesian-speaking ancestors despite the diversity of the cultures of the Filipinos.[10] The upper part of the Manunggul jar, as well as the cover, is carved with curvilinear scroll designs (reminiscent of waves on the sea) which are painted with hematite.[6]

.jpg)

Early Filipinos believed that a man is composed of a body, a life force called ginhawa, and a kaluluwa.[11] This explains why the design of the cover of the Manunggul Jar features three faces - the soul, the boatman, and the boat itself. On the faces of the figures and on the prow of the boat are eyes and mouth[8] rendered in the same style as other artifacts of Southeast Asia of that period. The two human figures in a boat represent a voyage to the afterlife. The boatman is holding a steering paddle while the one on his front shows hands crossed on his chest. The steersman's oar is missing its paddle, as is the mast in the center of the boat, against which the steersman would have braced his feet. The manner in which the hands of the front figure are folded across the chest is a widespread practice in the Philippines when arranging the corpse.[12]

The lid of the Manunggul Jar provides a clear example of a cultural link between the archeological past and the ethnographic present. It also signifies the belief of ancient Filipinos in life after death.

Jar burial

The practice of jar burial is an instance of secondary burial, in which only the bones of the deceased are reburied.[3] The jar itself was not interred.

See also

References

- Ortiz, Aurora R.; Erestain, Teresita E.; Guillermo, Alice G.; Montano, Myrna C.; Pilar, Santiago A. (1976). Art: Perception & Appreciation. Makati: Goodwill Trading Co. (published 2003). p. 266. ISBN 971-11-0933-6.

- "Museum of the Filipino People - Archaeological Treasures (Kaban ng Lahi)". National Museum of the Philippines. Retrieved 21 August 2010.

- pp. 40-41 Father Gabriel Casal & Regalado Trota Jose, Jr., Eric S. Casino, George R. Ellis, Wilhelm G. Solheim II, The People and Art of the Philippines, printed by the Museum of Cultural History, UCLA (1981)

- Miksic, J.N. (2003). Earthenware in Southeast Asia: Proceedings of the Singapore Symposium on Premodern Southeast Asian Earthenwares. NUS Press.

- Guillermo, A.R. (2012). History Dictionary of the Philippines. Scarescrow Press. p 275

- National Museum of the Philippines. (2014). Manunggul Jar. Retrieved November 20, 2015 from National Museum, Manunggul jar.

- Fox, R.B. (1970). The Tabon Cave: archaeological explorations and excavations on Palawan Island, Philippines. National Museum. University of Michigan. p 112-114

- Chua, M. (1995, April 27). The Arts of the Philippines. Retrieved November 22, 2015, from The manunggul jar as a vessel of history

- Batongbakal, L. (2014, August 27). 15 Most Intense Archaeological Discoveries in Philippine History. Retrieved November 22, 2015, from http://www.filipiknow.net/archaeological-discoveries-in-the-philippines/

- Wilhelm G. Solheim, II, “The Nusantao Hypothesis: The Origins and Spread of Austronesia Speakers,” Asian Perspectives XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 77-78; and Peter Bellwood, “Hypothesis for Austronesian Origins,” Asian Perspectives, XXVI, 1984-85, pp. 107-117.

- Zeus A. Salazar, “Ang Kamalayan at Kaluluwa: Isang Paglilinaw ng Ilang Konsepto sa Kinagisnang Sikolohiya” in Rogelia Pe-Pua, ed., Sikolohiyang Pilipino: Teorya, Metodo at Gamit (Quezon City: Surian ng Sikolohiyang Pilipino, 1982) pp. 83-92; and Prospero R. Covar, Kaalamang Bayang Dalumat ng Pagkataong Pilipino, p. 9-12 (Lekturang Propesoryal bilang tagapaghawak ng Kaalamang Bayang Pag-aaral sa taong 1992, Departamento ng Antropolohiya, Dalubhasaan ng Agham Panlipunan at Pilosopiya, Unibersidad ng Pilipinas. Binigkas sa Bulwagang Rizal, UP Diliman, Lungsod Quezon, Ika-3 ng Marso, 1993).

- Manunggul Jar And The Early Practice Of Burial In The Philippines. Retrieved November 15, 2015 http://noypicollections.blogspot.com/2011/08/manunggul-jar-and-early-practice-of.html.

External links

![]()

- "Manunggul Jar". National Museum of the Philippines. Retrieved 2013-07-02.