History of China–Japan relations

China and Japan share a long history through trade, cultural exchanges, friendship, and conflict. They are only separated by a narrow stretch of ocean. Through cross cultural contact, China and Korea has strongly influenced Japan; particularly from China with its writing system, architecture, culture, religion, philosophy, and law, many of which were introduced by the Kingdom of Baekje.

First evidences of Japan in Chinese historical records AD 1–300

%2C_297.jpg)

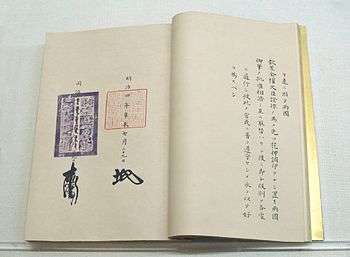

The first mention of the Japanese archipelago was in the Chinese historic text Book of Later Han, in the year 57, in which it was noted that the Emperor of the Han dynasty gave a golden seal to Wa (Japan). The King of Na gold seal was discovered in northern Kyūshū in the eighteenth century.[1] From then on Japan was repeatedly recorded in Chinese historical texts, at first sporadically, but eventually continuously as Japan matured into a notable power in the region.

There is a Chinese tradition that the first Chinese Emperor, Qin Shi Huang, sent several hundred people to Japan to search for medicines of immortality. During the third century, Chinese travelers reported that inhabitants of Japan claimed ancestry from Wu Taibo, a king of the Wu state (located in modern Jiangsu and Zhejiang) during the Warring States era.[2][3] They recorded examples of Wu traditions including ritual teeth-pulling, tattooing and carrying babies on backs. Other records at the time show that Japan already had the same customs recognized today. These include clapping during prayers, eating from wooden trays and eating raw fish (also a traditional custom of Jiangsu and Zhejiang before pollution made this impractical). Kofun era traditions appear in the records as the ancient Japanese built earthen mound tombs.

The first Japanese personage mentioned by the Wei Zhi (Records of Wei) is Himiko, the female shaman leader of a country with hundreds of states called Yamataikoku. Modern historical linguists believe Yamatai was actually pronounced Yamato.

Introduction of Chinese political system and culture in Japan AD 600–900

During the Sui dynasty and Tang dynasty, Japan sent many students on a limited number of Imperial embassies to China, to help establish its own footing as a sovereign nation in northeast Asia. After the fall of the Korean confederated kingdom of Baekje (with whom Japan was closely allied) to combined Tang and Silla forces, Japan was forced to seek out the Chinese state on its own, which in those times was a treacherous undertaking, thus limiting the successes of Japanese overseas contacts during this time.

Important elements brought back from China (and some which were transmitted through Baekje to Japan) included Buddhist teachings, Chinese customs and culture, bureaucracy, architecture and city planning. The Japanese kimono is very similar to the clothing of the Tang Dynasty, and many historians believe that the Japanese started wearing robes like what Tang royalty wore, eventually adapting the garb to match Japanese culture. The capital city of Kyoto was also planned according to Feng Shui elements from the Chinese capital of Chang'an. During the Heian period, Buddhism became one of the major religions, alongside Shinto.

The use of the Chinese model of Imperial government ceased by the tenth century, overtaken by traditional Japanese clan and family rivalries (Soga–Mononobe, Taira–Minamoto).

First recorded China-Japanese battle

In AD 663 the Battle of Baekgang took place, the first China-Japanese conflict in recorded history. The battle was part of the ancient relationships between the Korean Three Kingdoms (Samguk or Samhan), the Japanese Yamato, and Chinese dynasties. The battle itself came near the conclusion of this period with the fall of Baekje, one of the Samguk or three Korean kingdoms, coming on the heels of this battle.

The background of that large battle involves Silla (one of the Korean kingdoms) trying to dominate the Korean Peninsula by forging an alliance with the Tang dynasty, who were trying to defeat Goguryeo, an ongoing conflict that dated back to the Sui dynasty. At the time, Goguryeo was allied to Baekje, the third major Korean kingdom. Yamato Japan supported Baekje earnestly with 30,000 troops and sending Abe no Hirafu, a seasoned general who fought the Ainu in campaigns in eastern and northern Japan. As part of Silla's efforts to conquer Baekje, the battle of Baekgang was fought between Tang China, Baekje, Silla, and Yamato Japan.

The battle itself was a catastrophic defeat for the Yamato forces. Some 300 Yamato vessels were destroyed by a combined Silla–Tang fleet of half the number of ships, and thus the aid to Baekje from Yamato could not help on land, having been defeated at sea. Baekje fell shortly thereafter, in the same year.

Once Baekje was defeated, both Silla and Tang focused on the more difficult opponent, Goguryeo, and Goguryeo fell in 668 AD. For the most part, Silla, having been rivals with Baekje, also was hostile to Yamato Japan, which was seen as a brother state to Baekje, and this policy continued (with one pause between roughly AD 670–730) after Silla united most of what is now Korea and repelled Tang China from what is now the Korean peninsula. Yamato Japan was left isolated for a time and found itself having to forge ties with mainland Asia on its own, having had the most safe and secure pathway obstructed by a hostile Silla.

The prosperities of maritime trading 600–1600

Marine trades between China and Japan are well recorded, and many Chinese artifacts could be excavated. Baekje and Silla sometimes played the role of middleman, while direct commercial links between China and Japan flourished.

After 663 (with the fall of allied Baekje) Japan had no choice (in the face of hostility from Silla, which was temporarily deferred in the face of Tang imperialism – as Tang imperialism posed a threat both to Japan and unified Silla – but resumed in after 730 or so) but to directly trade with the Chinese dynasties. At first the Japanese had little long-range seafaring expertise of their own but eventually (some suggest with the aid of Baekje expatriates who fled their country when it fell) the Japanese improved their naval prowess as well as the construction of their ships.

The ports of Ningbo and Hangzhou had the most direct trading links to Japan and had Japanese residents doing business. The Ming dynasty decreed that Ningbo was the only place where Japanese–Chinese relations could take place.[4] Ningbo, therefore, was the destination of many Japanese embassies during this period. After going into Ningbo they then went to other cities in China. In 1523, two rival embassies were sent to Ningbo by Japan, then in a state of civil war known as the Sengoku period. One of the emissaries was a Chinese, Song Suqing, who had moved to Japan earlier.[5] Song Suqing became involved in a disagreement with a rival Japanese trade delegation, which led to the Ningbo Incident where the Japanese pillaged and plundered in the vicinity of Ningbo before escaping in stolen ships, defeating a Ming pursuing flotilla on the way. As a result of the incident, the port of Ningbo was closed to the Japanese – only two more Japanese missions were received (in 1540 and 1549) until the end of the Ming dynasty.

Direct trade with China was limited by the Tokugawa shogunate after 1633, when Japan decided to close all direct links with the foreign world, with the exception of Nagasaki which had Dutch and Chinese trading posts. Some trading was also conducted by the Shimazu clan of Satsuma province through the Ryukyu Islands and with the Ainu of Hokkaido.

Japanese piracy on China's coasts and Mongol invasions 1200–1600

Japanese pirates (or Wokou) were a constant problem, not only for China and Korea, but also for Japanese society, from the thirteenth century until Hideyoshi's failed invasions of Korea at the end of the sixteenth century. Japanese pirates were often from the undesirable parts of Japanese society, and the Japanese were just as happy to be (for the most part) rid of them as they were raiding more prosperous shores (at the time, Japan was ravaged by civil wars, and so while Korea, China, and the Mongol Empire were enjoying relative peace, prosperity, and wealth, the Japanese were upon hard times).

Ming dynasty during Hideyoshi's Korean invasions of 1592–1598

Toyotomi Hideyoshi was one of the three unifiers of Japan (Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu were the others). After subduing the Mōri and Shimazu clans, Hideyoshi had the dream of eventually conquering China but needed to cross through Korea.

When Hideyoshi received refusals to his demands by Korea to cross the country to Ming-dynasty China, he invaded Korea. In the first year of invasion in 1592, the Japanese reached as far as Manchuria under Katō Kiyomasa and fought the Jianzhou Jurchens. Seonjo (Korean king) requested aid from the Ming dynasty, but since Japanese advances were so fast, only small Ming forces were initially committed. Konishi Yukinaga, who garrisoned in Pyongyang in winter 1592, first encountered and defeated a force of 5,000 Chinese soldiers. In 1593, greater Chinese participation under General Li Rusong with an army of 45,000 took Pyongyang with artillery and drove the Japanese to the south, but the Japanese forces defeated them at the Battle of Byeokjegwan.

After 1593, there was a truce of about four years. During that time, Ming granted Hideyoshi the title as "King of Japan" as withdrawal conditions, but Hideyoshi felt it insulted the Emperor of Japan and demanded concessions including the daughter of the Wanli emperor. Further relations soured and war reignited. The second invasion was far less successful for Hideyoshi. The Chinese and Koreans were much more prepared and quickly confined and besieged the Japanese in the south until they were finally driven to the sea and defeated by the Korean admiral Yi Sun Shin. The invasion was a failure but severely damaged the Korean cities, culture and countryside with huge civilian casualties (the Japanese massacred civilians in captured Korean cities). The invasions also drained Ming China's treasury and left it weak against the Manchus, who eventually destroyed the Ming Dynasty and created the Qing dynasty in 1644.

Afterwards, Japan, under the Tokugawa shogunate adopted a policy of isolationism until forced open by Commodore Perry in the 1850s.

Ming and Qing dynasties and Edo period Tokugawa Japan

Chinese men visiting Edo period Tokugawa shogunate Japan patronized Japanese sex workers in brothels who were designated for them. Japanese women designated for Chinese male customers were known as Kara-yuki while Japanese women designated for Dutch men at Dejima were known as Oranda-yuki while Japanese women servicing Japanese men were called Nihon-yuki. Karayuki-san was then used for all Japanese women serving foreigners in sexual capacities during the Meiji period. The Japanese girls were offered to Japanese and Chinese customers at a low fee but the price of Japanese girls for Dutch sutomers was expensive and higher. Dutch traders were confined to the designated post at Dejima where Oranda-yuki prostitutes were sent. Initially Chinese men were much less restricted than the Dutch were at Dejimi, Chinese men could live all over Nagasaki and besides having sex with the kara-yuki Japanese prostitutes, the Chinese men could have sex with ordinary Japanese women since 1635 unlike Dutch men who were limited to prostitutes. Later the rules that applied to Dutch were applied to Chinese and Chinese were put in Jūzenji-mura into Tōjun-yashiki, a Chinese settlement in 1688 so they would have sex with the Kara-yuki Japanese prostitutes sent to them. Chinese men developed long term romances with the Japanese girls like the Chinese Suzhou (Su-chou) merchant Chen Renxie (Ch’ên Jên-hsieh) 陳仁謝 with the Japanese Azuyama girl Renzan 連山 who both committed suicide in a lover's pact in 1789, and the Chinese He Minde (Ho Min-tê) 何旻德 who pledged eternal love in Yoriai-machi with the Chikugoya Japanese girl Towa 登倭. She killed herself to join him in death when he was executed for forgery in 1690. The Chinese men were generous with their expensive presents to the Japanese girls and were praised by them for it. The Japanese girls violated Japan's laws which only permitted each to spend one night in the Chinese settlement by retracing their steps after reporting to the guards when they left the gate open in the morning. The Japanese issued laws and regulations considering the mixed children born to Japanese women from Maruyama and the foreigner Dutch and Chinese men in the Shōtoku era (1711-1716). The mixed children had to stay in Japan and could not be taken back to China or the Dutch country but their fathers could fund the children's education. The boy Kimpachi 金八 was born to the Iwataya Japanese girl Yakumo 八 and the Nanking Chinese captain Huang Zheqing 黃哲卿 (Huang Chê-ch’ing). He requested a permit from the Chief Administrator's Office of Nagasaki to trade goods to create a fund his son could live on for all his life, after coming back to Nagasaki at age 71 in 1723. A Hiketaya Japanese girl in Sodesaki 袖笑 gave birth to a son fathered by the Chinese Jiang Yunge 江芸閣 (Chiang Yün-ko) (Xinyi, Hsin-i 辛夷), a poet, painter and sea captain. Yanagawa Seigan and Rai Sanyu were his friends. Chinese dishes, delicacies, sweets and candies were introduced to Japan by Chinese men teaching their Japanese prostitute lover girls who to make them. In the Genroku era (1688-1704) a Chinese instructed the Japanese prostitute Ume how to make plum blossom shaped sugar and rice flour soft sweet called kōsakō. Her name also meant plum blossom. The songs were sung in the Tōsō-on The Kagetsu Entertainment (Kagetsu yokyō) booklet contained information about songs the Chinese men taught to their Japanese prostitute lovers showing that they were sang in Tōsō-on with instruments like hu-kung (two-stringed violin), ch’i-hsien-ch’in (seven-stringed dulcimer) and yüeh-ch’in (lute). The Japanese prostitutes of Maruyama who served the Chinese men in Nagasaki were taught dance, songs and music of Chinese origin. The gekkin (yüeh-ch’in) were used to play these Kyūrenhwan songs. The Kankan-odori dance accompanied one of these songs which spread in Edo and Kyōto as it gained fame. Exhibitions of the original Chinese style dance were performed in Edo by arranging for the sending of Nagasaki officials managing Chinese affairs and geisha to be sent there by Takahashi Sakuzaemon (1785-1829) who was the court astronomer of the Shogunate. He became famous due to the Siebold Incident. Later on the prostitutes were sent to service the Dutch at Dejima after they serviced Chinese at Maruyama being paid for by the Commissioners for Victualing.[6]

Meiji Restoration and the rise of the Japanese Empire 1868–1931

After the arrival of Commodore Perry and the forced opening of Japan to western trading, Japan realized it needed to modernize to avoid the humiliation suffered by China during the First and Second Opium Wars. Anti-Tokugawa tozama daimyōs[lower-alpha 1] led by the Shimazu and Mori clans overthrew the Tokugawa shogunate during the Meiji Restoration and restored the Japanese Emperor as head of state. Afterwards, Japan initiated structural reforms resulting in rapid modernization, industrialization, militarization and imperialism modeled after the imperialistic Western powers.

Conflict after 1870

As Japan modernized and built a strong economy and military, the smaller country grew in power. Friction between China and Japan arose from the 1870s from Japan's control over the Ryukyu Islands, rivalry for political influence in Korea and trade issues.[7] Japan, having built up a stable political and economic system with a small but well-trained army and navy, surprised the world with its easy victory over China in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1894–95. Japanese soldiers massacred the Chinese after capturing Port Arthur on the Liaotung Peninsula. In the harsh Treaty of Shimonoseki of April 1895, China recognized the independence of Korea, and ceded to Japan Formosa, the Pescatores Islands and the Liaotung Peninsula. China further paid an indemnity of 200 million silver taels, opened five new ports to international trade, and allowed Japan (and other Western powers) to set up and operate factories in these cities. However, Russia, France, and Germany saw themselves disadvantaged by the treaty and in the Triple Intervention forced Japan to return the Liaotung Peninsula in return for a larger indemnity. The only positive result for China came when those factories led the industrialization of urban China, spinning off a local class of entrepreneurs and skilled mechanics.[8]

Japanese troops participated in the Boxer Rebellion in 1900. The Chinese were again forced to pay another huge indemnity, but Japan was pressured to accept much less by the United States. Rivalries between the imperialist nations and the American Open Door Policy prevented China from being carved up into many colonies.[9] On the other hand, the Japanese government and individuals provided assistance to Sun Yat-sen and other members of the Tongmenghui who were instrumental in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of the Republic of China.

First World War

Japanese and British military forces in 1914 liquidated Germany's holdings in China. Japan occupied the German military colony in Qingdao, and occupied portions of Shandong Province. China was financially chaotic, highly unstable politically, and militarily very weak. Its best hope was to attend the postwar peace conference, and hope to find friends would help block the threats of Japanese expansion. China declared war on Germany in August 1917 as a technicality to make it eligible to attend the postwar peace conference. They planned to send a combat unit to the Western Front, but never did so.[10][11] British diplomats were afraid that the U.S. and Japan would displace Britain's leadership role in the Chinese economy. They sought to play Japan and the United States against each other, while at the same time maintaining cooperation among all three nations against Germany.[12]

In January 1915, Japan secretly issued an ultimatum of Twenty-One Demands to the Chinese government. They included Japanese control of former German rights, 99 year leases in southern Manchuria, an interest in steel mills, and concessions regarding railways. China did have a seat at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. However it was refused a return of the former German concessions and China had to accept the Twenty-One demands. A major reaction to this humiliation was a surge in Chinese nationalism expressed in the May Fourth Movement.[13]

Second Sino-Japanese War

In the beginning of the Shōwa period, the Japanese wanted to occupy Manchuria for its resources. Due to the fractious nature of China during the Warlord Era, and latterly the Chinese Civil War, the Japanese were able to gain influence in the region through espionage, diplomacy, and use of force. Two notable examples are the assassination of Zhang Zuolin, and the Mukden Incident. The latter was used by Japan as justification for the invasion of Manchuria and establishment of a friendly state, Manchukuo.[14]

In the period between the Mukden Incident in 1931 and the official beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 there were intermittent clashes and engagements between Japanese and the various Chinese forces. These engagements were collectively described by the Japanese government as "incidents" to downplay the conflict. This was primarily to prevent the United States deeming the conflict an actual war, and thus placing an embargo upon Japan as per the neutrality acts. The incidents collectively placed pressure on China to sign various agreements to Japan's benefit. These included the demilitarisation of Shanghai, the He–Umezu Agreement, and the Chin–Doihara Agreement. The period was turbulent for the Chinese Nationalists, as it was mired in a civil war with the Chinese Communists and maintained an uneasy truce with remnant warlords, who nominally aligned with Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek (Jiang Jieshi), following the Northern Expedition. This period also saw the Chinese Nationalists' pursuit in modernizing its National Revolutionary Army, through the assistance of Soviet, and later German, advisors.

In July 1937 the conflict escalated after a significant skirmish with Chinese forces at the Marco Polo Bridge. This marked the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War. Chinese nationalist forces retaliated by attacking Shanghai. The Battle of Shanghai lasted for several months, concluding with Chinese defeat on November 26, 1937.

Following this battle, Japanese advances continued to the south and west. A contentious aspect of these Japanese campaigns are the war crimes committed against Chinese people. The most infamous example was the Rape of Nanking, when Japanese forces subjected the population to looting, mass rape, massacres, and other crimes. Other, less publicised, atrocities were committed during Japanese advances and it's estimated that millions of Chinese civilians were killed. Various attempts to quantify the crimes committed have proved contentious, and at times divisive.

The war from 1938 onwards was marked by Chinese use of guerilla tactics to stall advances, and retreat to the deep interior where necessary. This eventually limited Japanese advances because of supply-line limitations – the Japanese were unable to adequately control remote areas but they did control practically all the major cities and ports, as well as air space.

World War II

By 1938, the United States increasingly was committed to supporting China and, with the cooperation of Britain and the Netherlands, threatening to restrict the supply of vital materials to the Japanese war machine, especially oil. The Japanese army, after sharp defeats by the Russians, wanted to avoid war with the Soviet Union, even though it would have aided the German war against the USSR. The Navy, increasingly threatened by the loss of its oil supplies, insisted on a decision, warning the alternatives were a high risk war, the Japan might lose, or a certain dissent into third class status and a loss of China and Manchuria. Officially the Emperor made the decision, but he was told by a key civilian official on 5 November 1941:

- it is impossible, from the standpoint of our domestic political situation and of our self-preservation, to accept all of the American demands....we cannot let the present situation continue. If we miss the present opportunity to go to war, we will have to submit to American dictation. Therefore, I recognize that it is inevitable that we must decide to start a war against the United States. I will put my trust in what it have been told: namely, that things will go well in the early part of the war; and that although we will experience increasing difficulties as the war progresses, there is some prospect of success.[15]

The Emperor became fatalistic about going to war, as the military assumed more and more control. Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe was replaced by the war cabinet of General Hideki Tojo (1884-1948), who demanded war. Tōjō had his way and the attack was made on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, as well as British and Dutch strong points. the main American battle fleet was disabled, and in the next 90 days Japan made remarkable advances including the Dutch East Indies, the Philippines, Malaya and Singapore.[16]

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the entry of the US into the war, fighting in the Pacific, and South East and South West Asia, significantly weakened the Japanese.

Occupation

After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet invasion of Japanese-occupied Manchuria, Japan surrendered.

The Republic of China (ROC) administrated Taiwan after Japan's unconditional surrender in 1945, following a decision by the Allied Powers at the Cairo Conference in 1943. The ROC moved its central government to Taiwan in December 1949, following the victory of the PRC in the Chinese Civil War. Later, no formal transfer of the territorial sovereignty of Taiwan to the PRC was made in the post-war San Francisco Peace Treaty, and these arrangements were confirmed in the Treaty of Taipei concluded by the ROC and Japan in 1952. At the time, the Taiwanese authorities (the Chinese Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT)) were recognized by Japan, not communist China (the People's Republic of China, or PRC). As such, the KMT did not accept Japanese reparations only in the name of the ROC government. Later, the PRC also refused reparations in the 1970s. See more details in the section about World War II reparations and the statement by Japanese Prime Minister Tomiichi Murayama (August, 1995).

See also

- International relations of the Great Powers (1814–1919)

- China–Japan relations, since 1949

- Republic of China–Japan relations

Notes

- major clans who sided against Tokugawa Ieyasu during the battle of Sekigahara in 1600

References

- "Gold Seal (Kin-in)". Fukuoka City Museum. Retrieved 2013-08-05.

- Encounters of the Eastern Barbarians, Wei Chronicles

- Brownlee, John S. (2011-11-01). Japanese Historians and the National Myths, 1600–1945: The Age of the Gods and Emperor Jinmu. UBC Press. ISBN 9780774842549.

- Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 420. ISBN 0521497817. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Official relations with Japan could only be conducted through the port of Ning-po, at the north-eastern tip of Chekiang;

- Jacques Gernet (1996). A history of Chinese civilization (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 421. ISBN 0-521-49781-7. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Thanks to the embassies, over a hundred known Japanese monks were thus able to come to China in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, visiting, on the way from Ning-po to Peking, Hangchow, Soochow, Nanking, the valley of the Huai and Tientsin, and make contact with Chinese literai. . . There was a case of a rich Chinese merchant by the name of Sung Su-ch'ing (1496–1523), a native of Chekiang, who, after trading with Japan and settling down there in 1510, formed part of the Japanese embassy which arrived in Ning-po in 1523.

- Vos, Fritz (December 2014). Breuker, Remco; Penny, Benjamin (eds.). "FORGOTTEN FOIBLES: LOVE AND THE DUTCH AT DEJIMA (1641–1854)". East Asian History. Published jointly by The Australian National University and Leiden University (39): 139–52. ISSN 1839-9010.

- Seo-Hyun Park, "Changing Definitions of Sovereignty in Nineteenth-Century East Asia: Japan and Korea Between China and the West". Journal of East Asian Studies 13#2 (2013): 281–307.

- William T. Rowe (2010). China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. Harvard UP. p. 234. ISBN 9780674054554.

- Yoneyuki Sugita, "The Rise of an American Principle in China: A Reinterpretation of the First Open Door Notes toward China," in Richard Jensen, Jon Davidann, Yoneyuki Sugita, eds., Trans-Pacific Relations: America, Europe, and Asia in the Twentieth Century (2003) pp. 3–20 online.

- Stephen G. Craft, "Angling for an Invitation to Paris: China's Entry into the First World War". International History Review 16#1 (1994): 1–24.

- Guoqi Xu, "The Great War and China's military expedition plan". Journal of Military History 72#1 (2008): 105–140.

- Clarence B. Davis, "Limits of Effacement: Britain and the Problem of American Cooperation and Competition in China, 1915–1917". Pacific Historical Review 48#1 (1979): 47–63. in JSTOR

- Zhitian Luo, "National humiliation and national assertion-The Chinese response to the twenty-one demands" Modern Asian Studies (1993) 27#2 pp 297–319.

- Barnouin, Barbara; Changgen, Yu (1998). Chinese Foreign Policy during the Cultural Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 113–116. ISBN 0-7103-0580-X.

- Quoted in Marius B. Jansen, Japan and China: from War to Peace, 1894–1972 (1975) p 405.

- Noriko Kawamura, "Emperor Hirohito and Japan's Decision to Go to War with the United States: Reexamined." Diplomatic History 2007 31#1: 51-79. online

Further reading

- Boyle, John Hunter. China and Japan at war, 1937–1945: the politics of collaboration (Stanford University Press, 1972)

- Chi, Madeleine. China Diplomacy, 1914–1918 (Harvard Univ Asia Center, 1970).

- Coox, Alvin. China and Japan: The Search for Balance Since World War I (ABC-Clio, 1978).

- Hiroshi, Nakanishi, et al. The golden age of the US-China-Japan triangle, 1972-1989 (Harvard Asia Center, 2002).

- Ikei, Masaru. "Japan's Response to the Chinese Revolution of 1911." Journal of Asian Studies 25.2 (1966): 213–227. online

- Jansen, Marius B. Japan and China From War to Peace 1894 - 1972 (1975)

- Jung-Sun, Han. "Rationalizing the Orient: The 'East Asia Cooperative Community' in Prewar Japan". Monumenta Nipponica (2005): 481–514. in JSTOR

- Kokubun, Ryosei, et al. Japan–China Relations in the Modern Era (Routledge, 2017).

- Matsusaka, Yoshihisa Tak. The Making of Japanese Manchuria, 1904–1932 (Harvard University Asia Center, 2001).

- Morley, James William, ed. Japan's Foreign Policy, 1868–1941: A Research Guide (Columbia UP, 1974), policies toward China pp 236–64; historiography.

- Morley, James William, ed. The China Quagmire Japan's Expansion on the Asian Continent 1933-1941: Selected Translations from Taiheiyō Sensō E No Michi: Kaisen Gaikō Shi (Columbia University Press, 1983), primary sourced.

- Morse, Hosea Ballou. The international relations of the Chinese empire Vol. 1 (1910) to 1859; online;

- Nobuya, Bamba. Japanese Diplomacy in a Dilemma: New Light on Japan's China Policy, 1924–29 (U of British Columbia Press, 1973).

- Nish, Ian. (1990) "An Overview of Relations between China and Japan, 1895–1945." China Quarterly (1990) 124 (1990): 601–623. online

- Reynolds, D.R., “A golden age forgotten: Japan-China relations, 1898–1907,” Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 4th series, Vol. 2 (1987), pp. 93–153.

- Sun, Youli, and You-Li Sun. China and the Origins of the Pacific War, 1931–1941 (St. Martin's Press, 1993)

- Verschuer, Charlotte von. Across the Perilous Sea: Japanese Trade with China and Korea from the Seventh to the Sixteenth Centuries (Cornell University East Asia Program. 2006)

- Vogel, Ezra F. China and Japan: Facing History (2019) excerpt scholarly survey over 1500 years

- Wang, Zhenping: Ambassadors from the Islands of the Immortals: China–Japan Relations in the Han–Tang Period. (U of Hawaii Press, 2005) 387 pp.

- Yick, Joseph. "Communist-Puppet collaboration in Japanese-Occupied China: Pan Hannian and Li Shiqun, 1939–43". Intelligence and National Security 16.4 (2001): 61–88.

- Yoshida, Takashi. The making of the" Rape of Nanking": history and memory in Japan, China, and the United States (Oxford UP, 2006).

- Zhang, Yongjin. China in the International System, 1918–20: the Middle Kingdom at the periphery (Macmillan, 1991)

.svg.png)