Kofun

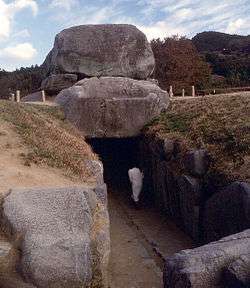

Kofun (古墳, from Sino-Japanese "ancient grave") are megalithic tombs or tumuli in Japan, constructed between the early 3rd century and the early 7th century AD. The term is the origin of the name of the Kofun period, which indicates the middle 3rd century to early–middle 6th century. Many Kofun have distinctive keyhole-shaped mounds (zempō-kōen fun (前方後円墳)), which are unique to ancient Japan. The Mozu-Furuichi kofungun or tumulus clusters were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2019, while Ishibutai Kofun is one of a number in Asuka-Fujiwara residing on the Tentative List.[1][2]

Overview

The kofun tumuli have assumed various shapes throughout history. The most common type of kofun is known as a zenpō-kōen-fun (前方後円墳), which is shaped like a keyhole, having one square end and one circular end, when viewed from above. There are also circular-type (empun (円墳)), "two conjoined rectangles" typed (zenpō-kōhō-fun (前方後方墳)), and square-type (hōfun (方墳)) kofun. Orientation of kofun is not specified. For example, in the Saki Kofun group, all of the circular parts are facing north, but there is no such formation in the Yanagimoto kofun group. Haniwa, terracotta figures, were arrayed above and in the surroundings to delimit and protect the sacred areas.

Kofun range from several metres to over 400m long. The largest, which has been attributed to Emperor Nintoku, is Daisen Kofun in Sakai City, Osaka Prefecture.

The funeral chamber was located beneath the round part and comprised a group of megaliths. In 1972, the unlooted Takamatsuzuka Tomb was found in Asuka, and some details of the discovery were revealed. Inside the tightly assembled rocks, white lime plasters were pasted, and colored pictures depict the 'Asuka Beauties' of the court as well as constellations. A stone coffin was placed in the chamber, and accessories, swords, and bronze mirrors were laid both inside and outside the coffin. The wall paintings have been designated national treasures and the grave goods as important cultural property, while the tumulus is a special historic site.[3][3][4]

Locations and number

Kofun burial mounds and their remains have been found all over Japan, including remote islands such as Nishinoshima.[5]

A total of 161,560 kofun tomb sites have been found as of 2001. Hyōgo Prefecture has the most of all prefectures (16,577 sites), and Chiba Prefecture has the second most (13,112 sites).[6]

History

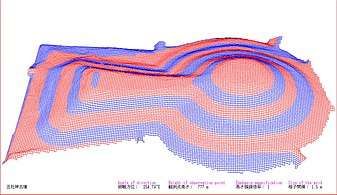

(Gosashi Kofun (Nara, Nara), 4th century)

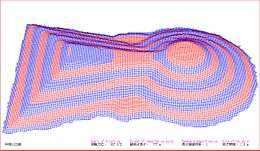

(Nakatsuyama Kofun (Fujiidera, Osaka), 5th century)

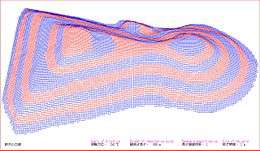

(Danpusan Kofun (Nagoya), 6th century)

Yayoi period

Most of the tombs of chiefs in the Yayoi period were square-shaped mounds surrounded by ditches. The most notable example in the late Yayoi period is Tatetsuki Mound Tomb in Kurashiki, Okayama. The mound is about 45 metres wide and 5 metres high and has a shaft chamber. Broken pieces of Tokushu-kidai, cylindrical earthenware, were excavated around the mound.

Another prevalent type of Yayoi period tomb is the Yosumi tosshutsugata funkyūbo, a square mound with protruding corners. These tombs were built in the San'in region, a coastal area off the Sea of Japan. Unearthed articles indicate the existence of alliances between native tribes in the region.

Early Kofun period

One of the first keyhole-shaped kofun was built in the Makimuku area,[7] the southeastern part of the Nara Basin. Hashihaka Kofun, which was built in the middle of the 3rd century AD, is 280 metres long and 30 metres high. Its scale is obviously different from previous Yayoi tombs. During the next three decades, about 10 kofun were built in the area, which are now called as the Makimuku Kofun Group. A wooden coffin was placed on the bottom of a shaft, and the surrounding walls were built up by flat stones. Finally, megalithic stones formed the roof. Bronze mirrors, iron swords, magatama, clay vessels and other artifacts were found in good condition in undisturbed tombs. Some scholars assume the buried person of Hashihaka kofun was the shadowy ancient Queen Himiko of Yamataikoku, mentioned in the Chinese historical texts. According to the books, Japan was called Wa, which was the confederation of numerous small tribes or countries. The construction of gigantic kofun is the result of the relatively centralized governmental structure in the Nara Basin, possibly the origin of the Yamato polity and the Imperial lineage of Japan.

Mid-Kofun period

During the 5th century AD, the construction of keyhole kofun began in Yamato Province; continued in Kawachi, where gigantic kofun, such as Daisen Kofun of the Emperor Nintoku, were built; and then throughout the country. The proliferation of keyhole kofun is generally assumed to be evidence of the Yamato court's expansion in this age. However, some argue that it simply shows the spread of culture based on progress in distribution, and has little to do with a political breakthrough.

In recent years, South Korea has begun to allocate more resources toward archaeology, and keyhole tombs have been found around the Yeongsan River basin, during the mid-Baekje Era. The keyhole tombs that have thus far been discovered on the Korean peninsula were built between the 5th and 6th centuries AD.[8] There remains questions over whether the tombs were made for Japanese aristocrats and mercenaries loyal to Baekje, Japanese merchants who controlled the region, or a class independent from both Baekje and Yamato Japan.[8]

Late Kofun period

Keyhole-shaped kofun disappeared in the late 6th century AD, probably due to the drastic reformation in the Yamato court, where Nihon Shoki records the introduction of Buddhism during this era.

UNESCO Kofun Group

This list includes the "Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan",[9] which was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site on 6 July 2019.[10]

| Name | Coordinates | Property | Buffer Zone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aoyama Kofun | 34°33′20.99″N 135°36′2″E | 0.51 ha (1.3 acres) | |

| Chuai-tenno-ryo Kofun | 34°33′56.99″N 135°35′38.99″E | 9.34 ha (23.1 acres) | 350 ha (860 acres) |

| Dogameyama Kofun | 34°33′46″N 135°28′56″E | 0.06 ha (0.15 acres) | |

| Genemonyama Kofun | 34°33′54.69″N 135°29′29.38″E | 0.09 ha (0.22 acres) | |

| Gobyoyama Kofun | 34°33′16.98″N 135°29′26.98″E | 5.4 ha (13 acres) | |

| Hachizuka Kofun | 34°34′4.5″N 135°35′43.58″E | 0.31 ha (0.77 acres) | |

| Hakayama Kofun | 34°33′28″N 135°36′15.99″E | 4.34 ha (10.7 acres) | |

| Hakuchoryo Kofun | 34°33′3.98″N 135°36′15.99″E | 5.65 ha (14.0 acres) | |

| Hanzei-tenno-ryo Kofun | 34°34′33.99″N 135°29′17.98″E | 4.06 ha (10.0 acres) | |

| Hatazuka Kofun | 34°33′24″N 135°28′58″E | 0.38 ha (0.94 acres) | |

| Hazamiyama Kofun | 34°33′42″N 135°36′7.98″E | 1.5 ha (3.7 acres) | |

| Higashiumazuka Kofun | 34°33′50″N 135°36′43.98″E | 0.03 ha (0.074 acres) | |

| Higashiyama Kofun | 34°33′42.09″N 135°36′20.7″E | 0.41 ha (1.0 acre) | |

| Ingyo-tenno-ryo Kofun | 34°34′23″N 135°37′0″E | 6.43 ha (15.9 acres) | |

| Itasuke Kofun | 34°33′11″N 135°29′8.98″E | 2.42 ha (6.0 acres) | |

| Joganjiyama Kofun | 34°33′24.99″N 135°36′6.99″E | 0.52 ha (1.3 acres) | |

| Komoyamazuka Kofun | 34°34′0.9″N 135°29′3.38″E | 0.08 ha (0.20 acres) | |

| Komuroyama Kofun | 34°34′5″N 135°36′33.99″E | 2.92 ha (7.2 acres) | |

| Kurizuka Kofun | 34°33′46″N 135°36′45″E | 0.11 ha (0.27 acres) | |

| Magodayuyama Kofun | 34°33′36″N 135°29′06″E | 0.45 ha (1.1 acres) | |

| Maruhoyama Kofun | 34°34′1″N 135°29′6.99″E | 0.69 ha (1.7 acres) | |

| Minegazuka Kofun | 34°33′7.98″N 135°35′49.79″E | 1.12 ha (2.8 acres) | |

| Mukohakayama Kofun | 34°33′25.98″N 135°36′21.98″E | 0.33 ha (0.82 acres) | |

| Nabezuka Kofun | 34°34′17.6″N 135°36′52.58″E | 0.14 ha (0.35 acres) | |

| Nagatsuka Kofun | 34°33′27.6″N 135°29′15.28″E | 0.51 ha (1.3 acres) | |

| Nagayama Kofun | 34°34′5″N 135°29′11.99″E | 0.97 ha (2.4 acres) | |

| Nakatsuhime-no-mikoto-ryo Kofun | 34°34′11.8″N 135°36′44.6″E | 7.23 ha (17.9 acres) | |

| Nakayamazuka Kofun | 34°34′5″N 135°36′48.98″E | 0.24 ha (0.59 acres) | |

| Nintoku-tenno-ryo Kofun, Chayama Kofun and Daianjiyama Kofun | 34°33′52.98″N 135°29′15.98″E | 46.4 ha (115 acres) | |

| Nisanzai Kofun | 34°32′47.99″N 135°29′57.98″E | 10.53 ha (26.0 acres) | |

| Nishiumazuka Kofun | 34°33′21.98″N 135°36′24″E | 0.07 ha (0.17 acres) | |

| Nonaka Kofun | 34°33′32″N 135°36′15.99″E | 0.19 ha (0.47 acres) | |

| Ojin-tenno-ryo Kofun, Konda-maruyama Kofun and Futatsuzuka Kofun | 34°33′43.98″N 135°36′33.99″E | 28.92 ha (71.5 acres) | |

| Osamezuka Kofun | 34°33′31.88″N 135°29′17.08″E | 0.07 ha (0.17 acres) | |

| Otorizuka Kofun | 34°34′1″N 135°36′32″E | 0.51 ha (1.3 acres) | |

| Richu-tenno-ryo Kofun | 34°33′14″N 135°28′38.99″E | 17.3 ha (43 acres) | |

| Shichikannon Kofun | 34°33′24.4″N 135°28′46.5″E | 0.09 ha (0.22 acres) | |

| Suketayama Kofun | 34°34′5″N 135°36′47″E | 0.12 ha (0.30 acres) | |

| Tatsusayama Kofun | 34°33′39.98″N 135°28′59.99″E | 0.34 ha (0.84 acres) | |

| Terayama-minamiyama Kofun | 34°33′21.98″N 135°28′47.99″E | 0.42 ha (1.0 acre) | |

| Tsudo-shiroyama Kofun | 34°34′55″N 135°35′36.98″E | 4.74 ha (11.7 acres) | 23 ha (57 acres) |

| Tsukamawari Kofun | 34°33′46″N 135°29′25.98″E | 0.07 ha (0.17 acres) | |

| Yashimazuka Kofun | 34°34′5″N 135°36′51.99″E | 0.25 ha (0.62 acres) | |

| Zenemonyama Kofun | 34°33′9.6″N 135°29′12.38″E | 0.1 ha (0.25 acres) | |

| Zenizuka Kofun | 34°33′19.19″N 135°29′3.58″E | 0.3 ha (0.74 acres) |

Aerial photos

Oyamato, Yanagimoto and Makimuku Kofun Group, Nara Prefecture, 3rd century

Oyamato, Yanagimoto and Makimuku Kofun Group, Nara Prefecture, 3rd century Saki Tatanami Kofun Group and the Heijō-kyō site, Nara Prefecture, 4th century

Saki Tatanami Kofun Group and the Heijō-kyō site, Nara Prefecture, 4th century Furuichi Kofun Group, Osaka Prefecture, 5th century

Furuichi Kofun Group, Osaka Prefecture, 5th century

See also

- William Gowland, a British engineer who made the first survey for Saki kofun group

- Ernest Satow, a British diplomat who wrote about kofun in Kozuke for the Asiatic Society of Japan

- Fukiishi, stones used to cover kofun

Notes

- "Mozu-Furuichi Kofungun, Ancient Tumulus Clusters". UNESCO. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "Asuka-Fujiwara: Archaeological sites of Japan's Ancient Capitals and Related Properties". UNESCO. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- "Database of National Cultural Properties". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- "Database of National Cultural Properties". Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 14 May 2011.

- 島根県遺跡データベース Archaeological Database of Shimane(Japanese)

- 兵庫県教育委員会 兵庫県の遺跡・遺物数の全国的な位置(pdf file, Japanese)

- Krako-kagi Archaeological Museum (2013). "たわらもと2013発掘速報展". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-01.

- Yoshii, Hideo (Kyoto University). "Keyhole-shaped tombs in Korean Peninsula".

- "Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group: Mounded Tombs of Ancient Japan". UNESCO. 6 July 2019.

- "Seven cultural sites inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List". UNESCO. 6 July 2019.

References

- 飛鳥高松塚 (Takamatsuzuka, Asuka), 橿原考古学研究所編, 明日香村, 1972.

- 前方後円墳 (Keyhole-shaped kofun), 上田宏範, 学生社, 東京, 1969.

- 前方後円墳と古代日朝関係 (Keyhole-shaped kofun and diplomatic relations between ancient Japan and Korea), 朝鮮学会編, 東京, 同成社, 2002.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to kofun. |

- Kofun - Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Japanese Archaeology: Kofun Culture

- (in Japanese) Decorated Kofun Database

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties