Demerara

Demerara (Dutch: Demerary) is a historical region in the Guianas on the north coast of South America which is now part of the country of Guyana. It was a Dutch colony until 1815 and a county of British Guiana from 1838 to 1966. It was located about the lower courses of the Demerara River, and its main town was Georgetown.

Colony of Demerara Kolonie Demerary | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1745–1815 | |||||||||

Flag

Coat of arms

| |||||||||

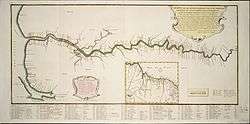

The Demerara colony in 1759 (Note this map has East at its top.) See here for its exact location (6° 48' N 58° 10' W). | |||||||||

| Status | Dutch colony | ||||||||

| Capital | Fort Zeelandia (1745–1755) Borsselen (1755–1782) Stabroek (1782–1815) | ||||||||

| Common languages | Dutch | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | 1745 | ||||||||

• Ceded to the United Kingdom | November 20 1815 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Guyana | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||

(1830s).jpg)

The name "Demerara" comes from a variant of the Arawak word "Immenary" or "Dumaruni" which means "river of the letterwood (Brosimum aubletii)".[1] Demerara sugar is so named because originally it came from sugar cane fields in the colony of Demerara.

History

Demerara was first mentioned in 1691 as a trading post.[2] On 18 October 1745, Demerara was created as a separate colony, even though it was located on an unoccupied part of Essequibo, because the people from the province of Holland wanted to settle there and Essequibo was part of Zeeland.[3] In the founding documents, it was mentioned that the colonists should live in peace with the Amerindian population and respect their territories, because they fought with the colony of Essequibo against the French privateers and helped to chase them off. The Amerindian were considered free people, and they were not allowed to enslave them.[4]

The first planter was Andries Pieterse who already owned a plantation in Essequibo. Half a year later, there were 18 large sugar plantations and 50 smaller plantations.[5] The colony was initially governed from Fort Zeelandia by Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande, the governor of Essequibo. In 1750 he appointed his son Jonathan as Commander of Demerara.[6]

Demerara grew rapidly,[7] and attracted many English planters.[8] The Dutch West India Company, who had a monopoly on the slave trade, was unable to supply them, leading to illegal smuggling from English colonies.[9]

In 1755, Gedney Clarke, a Barbados merchant and plantation owner,[10] requested political representation,[11] therefore the administration was moved to the island of Borsselen,[8] 20 miles (32 km) upriver near plantation Soesdyke which was owned by the commander of Demerara.[12] The decision was criticised because the island was hard to defend,[13] and the planters had started to build houses around the guard post near the mouth of the river. That settlement later became known as Stabroek,[8] and in 1782 the capital of the colony.[14] The town was renamed Georgetown in 1812.[15]

In 1763, a slave uprising took place in neighbouring Berbice. Governor van 's Gravesande formed an alliance with the Amerindian Arawak, Kalina, Warao and Akawaio[16] tribes,[17] and prevented the uprising from spreading to Demerara and Essequibo.[8] 50 soldiers from Demarara were sent to Berbice as assistance.[18] The slave uprisings were source of concern: in a 1767 letter to Frederick the Great, the King of Prussia, which aimed to promote the colony for German planters, a request was added for 100 soldiers.[19]

In 1780, there were almost 200 plantations in Demerara compared to 129 in Essequibo.[20] Demerara had become more successful than Essequibo.[18][8] The rivalry between the colonies resulted in the creation of a combined Court of Policy in Fort Zeelandia.[21] The majority of the white population of the colony were English[8] and Scottish[22][23] planters.

Conquest and reconquest

In 1781, the American revolution induced the Dutch Republic to join with the Bourbon side against the British, a large fleet under Admiral Lord Rodney's command was sent to the West Indies, and after having made some seizures in the Caribbean Islands, a squadron was detached to take possession of the colonies of Essequibo and Demerara, which was accomplished[24] without even a fight.[25][26] The previous year, the colony produced 10,000 hogsheads of sugar, 5,000,000 pounds coffee and 800,000 pounds cotton.[26]

In 1782 the French took possession of the whole of the Dutch settlements, compelling Gov. Robert Kingston to surrender.[27] The opinion of the Dutch newspapers varied. The Leeuwarder Courant called it the loss of our Demerary,[28] while the Hollandsche historische courant described it as a pleasant reconquest.[29] The peace of Paris, which occurred in 1783, restored these territories to the Dutch.[30]

The British recaptured Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice in 1796.[23] A deal was struck with the colony: all laws and customs could remain, and the citizens were equal to British citizens. Any government official who swore loyalty to the British crown could remain in function.[23] They returned the colony to the Dutch in 1802 under the terms of the Peace of Amiens,[31] but re-took control of it a year later.[31]

On 28 April 1812,[32] the British combined the colonies of Demerara and Essequibo into the colony of Demerara-Essequibo.[31] They were ceded to Britain on 13 August 1814. On 20 November 1815, the Netherlands ratified the agreement.[33]

Slave rebellion

Large slave rebellions broke out in West Demerara in 1795 and on the East Coast of Demerara in 1823.[34] Although these rebellions were easily and bloodily crushed, according to Winston McGowan, they may have had a long-term impact in ending slavery:

The 1823 revolt had a special significance not matched by the earlier Berbice uprising. It attracted attention in Britain inside and outside Parliament to the terrible evil slavery and the need to abolish it. This played a part, along with other humanitarian, political and economic factors, in causing the British parliament ten years later in 1833 to take the momentous decision to abolish slavery in British Guiana and elsewhere in the British Empire with effect from 1 August 1834. After serving four years of a modified form of slavery euphemistically called apprenticeship, the slaves were finally freed on 1 August 1838.

— [35]

Dissolution

On 21 July 1831, Demerara-Essequibo united with Berbice as British Guiana, now Guyana.[36] In 1838, Demerara was made one of the three counties of Guiana, the other two being Berbice and Essequibo.[37] In 1958, the county was abolished when Guiana was subdivided into districts. Currently, historical Demerara is part of (and the name is used in) the Guyanese administrative regions of Demerara-Mahaica, Essequibo Islands-West Demerara, and Upper Demerara-Berbice.[37]

Notable Demerarans

- Sir James Douglas (1803-1877), Governor of the Colony of Vancouver Island (1851–64) and the Colony of British Columbia (1858–64).

- Rev. Joseph Ketley (1802–1875), Congregational missionary, mid 19th century.

- John Edmonstone (late 18th century–mid 19th century), a freed slave who taught Charles Darwin taxidermy.[38]

Commanders of Demerara

- Jonathan Samuel Storm van 's Gravesande (†1761) (1750–1761)[39]

- Laurens Lodewijk van Bercheijk (†1765) (1761–1765)

- Jan Cornelis van den Heuvel (1765–1770)

- Paulus van Schuylenburgh (1772–1781)

- Antony Beaujon (22 April 1796 – 27 March 1802)

Governors of Demerara

- Robert Kingston (27 February 1781 – 1782)

- Louis Antoine Dazemard de Lusignan (1782)

- Armand Guy Simon de Coëtnempren, comte de Kersaint (*1742 – †1793) (1782)

- Georges Manganon de la Perrière (1783–1784)

Directors-general

- Laurens Storm van 's Gravesande (1752-1772)[39]

- Joseph Bourda (acting) (6 March 1784 – February 1785)

- Jan L'Éspinasse (February 1785 – 18 August 1789)

- Albertus Backer (18 August 1789 – 31 March 1793)

- Willem August van Sirtema, baron van Grovestins (31 March 1793 – May 1795)

- Antony Beaujon (*17... – †1805) (1795 – 22 April 1796)

- Antony Meertens (27 March 1802 – September 1803)

Lieutenant governors

- Robert Nicholson (September 1803 – 18 August 1804)

- Antony Beaujon (18 August 1804 – 19 October 1805)

- James Montgomery (acting) (19 October 1805 – 8 May 1806)

- Count Henri Guillaume (Henry William) Bentinck (*1765 – †1821) (8 May 1806 – February 1812)

- Hugh Lyle Carmichael (*1764 – †1813) (February 1812 – 11 May 1813)

- E. Codd (acting) (11 May 1813 – 23 May 1813)

- John Murray (23 May 1813 – 26 April 1824)

- Sir Benjamin d'Urban (26 April 1824 – 21 July 1831)

Leaders of rebellions

- 1823: Jack Gladstone of Plantation Success

- 1823: Quamina of Plantation Success

References

- Benn, Brindley H. (1962-06-30). "Guyana the Name". Thunder. Georgetown, Guyana. Archived from the original on May 1, 2008.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, p. 38.

- Hartsinck 1770, pp. 267-268.

- Hartsinck 1770, p. 270.

- Netscher 1888, p. 116.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, p. 40.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, p. 39.

- "Establishment of Demerara". Guyana Times International. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- Netscher 1888, p. 128.

- "The Rise and Fall of a Barbados Merchant". Washington Papers. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, p. 40, :The College of Kiezers, the electoral college, of Essequibo had refused to admit new members

- "The Wonderful Demerara River". Guyanese Online. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- Netscher 1888, p. 186.

- Netscher 1888, p. 149.

- Netscher 1888, p. 310.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, pp. 235-236: In September 1763, the Chief of the Akawaio paid a visit to the Governor of Essequibo in Fort Zeelandia with two slaves, three cut-off hands and reported that his tribe had killed 55 slaves. He wanted a reward, guns and ammunition.

- Esther Baakman. "Their power has been broken, the danger has passed." Dutch newspaper coverage of the Berbice slave revolt, 1763". Early Modern Low Countries Journal.

- Netscher 1888, p. 144.

- Storm van 's Gravesande & Villiers 1920, p. 311.

- Netscher 1888, pp. 149-150.

- Netscher 1888, p. 143.

- "How Scotland erased Guyana from its past". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 August 2020.

- A.N. Paasman (1984). "Reinhart: Nederlandse literatuur en slavernij ten tijde van de Verlichting". Digital Library for Dutch Literature. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- Hadden 2009, p. 64.

- Netscher 1888, p. 150.

- "Middelburgsche courant". Middelburgsche courant via Delpher (in Dutch). 1 May 1781. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Dalton 1855, p. 239.

- "Leeuwarder Courant". Leeuwarder Courant via Delpher (in Dutch). 23 March 1782. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- "Vrankrijk". Hollandsche historische courant via Delpher (in Dutch). 27 April 1782. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- Edler 2001, p. 185

- Schomburgk 1840, p. 86.

- Netscher 1888, p. 290.

- "Berbice". British Empire. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- McGowan, Winston (2000). "The distinctive features of the 1823 Demerara slave rebellion". Starbroeck News. Retrieved 2017-08-15.

- McGowan, Winston (2006). "The 1763 and 1823 slave rebellions (Part 2)". Stabroek News. Archived from the original on 2007-09-27. Retrieved 2006-12-07.

- "37. The Beginning of British Guiana". Guyana.org. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- Regions of Guyana at Statoids.com. Updated 20 June 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2013.

- "The Extraordinary Life of the Freed Slave Who Taught Darwin Taxidermy". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 11 August 2020.

- P.J. Blok & P.C. Molhuysen (1927). "Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek. Deel 7". Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). Retrieved 14 August 2020.

Further reading

- da Costa, Emilia Viotti. Crowns of Glory, Tears of Blood (1994). scholarly study of the Demerara slave rebellion of 1823.

- Dalton, Henry G (1855). The History of British Guiana: Comprising a General Description of the Colony: A narrative of some of the principal events from the earliest period of products and natural history. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Edler, F. (2001) [1911], The Dutch Republic and The American Revolution, Honolulu, Hawaii: University Press of the Pacific, ISBN 0-89875-269-8

- Hadden, James (2009). Hadden's Journal and Orderly Books. Applewood. ISBN 1-4290-1685-X.

- Hartsinck, J.J. (1770), Beschryving van Guiana, of de wilde kust in Zuid-America, Amsterdam: Gerrit TielenburgCS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Netscher, Pieter Marinus (1888). Geschiedenis van de koloniën Essequebo, Demerary en Berbice, van de vestiging der Nederlanders aldaar tot op onzen tijd (in Dutch). The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Oostindie, Gert. "‘British Capital, Industry and Perseverance’ versus Dutch ‘Old School’? The Dutch Atlantic and the Takeover of Berbice, Demerara and Essequibo, 1750-1815" BMGN: Low Countries Historical Review (2012) 127#4 pp 28–55.

- Schomburgk, Sir Robert H. (1840). A Description of British Guiana, Geographical and Statistical: Exhibiting Its Resources and Capabilities. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co. ISBN 978-0714619491.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sheridan, Richard B. "The condition of the slaves on the sugar plantations of Sir John Gladstone in the colony of Demerara, 1812-49." New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 76#3-4 (2002): 243-269.

- St Pierre, Maurice. "The 1823 Guyana Slave Rebellion: A Collective Action Reconsideration." Journal of Caribbean History 41#1/2 (2007): 142.

- Storm van 's Gravesande, Laurens; Villiers, J.A.J. de (1920). Storm van 's Gravesande: zijn werk en zijn leven uit zijne brieven opgebouwd (in Dutch). The Hague: Nijhoff.