History of French Guiana

The history of French Guiana spans many centuries. Before the first Europeans arrived, there was no written history in the territory. It was originally inhabited by a number of Native American peoples, among them the Kalina (Caribs), Arawak, Galibi, Palikur, Teko, Wayampi (also known as Oyampi), and Wayana. The first Europeans arrived in the expeditions of Christopher Columbus, shortly before 1500.

.jpg)

Beginnings of European involvement

In 1498 French Guiana was first visited by Europeans when Christopher Columbus sailed to the region on his third voyage and named it the "Land of Pariahs".[1] In 1608 the Grand Duchy of Tuscany sent an expedition to the area in order to create an Italian colony for the commerce of Amazonian products to Renaissance Italy, but the sudden death of Ferdinando I de' Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany stopped it.

In 1624 the French attempted to settle in the area, but was forced to abandon it in the face of hostility from the Portuguese, who viewed it as a violation of the Treaty of Tordesillas. However French settlers returned in 1630 and in 1643 managed to establish a settlement at Cayenne along with some small-scale plantations. This second attempt would again be abandoned following Amerindian attacks. In 1658 the Dutch West Indies Company seized French territory to establish the Dutch colony of Cayenne. The French returned once more in 1664, and founded a second settlement at Sinnamary (this was attacked by the Dutch in 1665).

In 1667 the English seized the area. Following the Treaty of Breda on 31 July 1667 the area was given back to France. The Dutch briefly occupied it for a period in 1676.

Consolidation of French rule

After the Treaty of Paris in 1763, which deprived France of almost all her possessions in the Americas other than Guiana and a few islands, Louis XV sent thousands of settlers to Guiana who were lured there with stories of plentiful gold and easy fortunes to be made. Instead they found a land filled with hostile natives and tropical diseases. One and a half years later only a few hundred survived. These fled to three small islands which could be seen off shore and named them the Iles de Salut (or "Islands of Salvation"). The largest was called Royal Island, another St. Joseph (after the patron saint of the expedition), and the smallest of the islands, surrounded by strong currents, Île du Diable (the infamous "Devil's Island"). When the survivors of this ill-fated expedition returned home, the terrible stories they told of the colony left a lasting impression in France.

In 1776, Pierre-Victor Malouet was appointed to the Colony,[2] who brought in Jean Samuel Guisan to establish agriculture in the colony.[3] The relatively good period ended in 1792 during the French Revolution, when the first prison for priests and political enemies opened in Sinnamary[4] which set a precedent.

During the Revolution, the National Convention voted to abolish slavery in February 1794, months after the rebelling slaves had already announced an abolition of slavery in Saint-Domingue. However, the 1794 decree was only implemented in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe and French Guiana, and was a dead letter in Senegal, Mauritius, Réunion and Martinique, the last of which had been conquered by the British, who maintained the institution of slavery on that Caribbean island.[5]

In 1794, after the death of Robespierre, 193 of his followers were sent to French Guiana. In 1797 the republican general Pichegru and many deputies and journalists were also sent to the colony. When they arrived they found that only 54 of the 193 deportées sent out three years earlier were left; 11 had escaped, and the rest had died of tropical fevers and other diseases. Pichegru managed to escape to the United States and then returned to France where he was eventually executed for plotting against Napoleon.

Later on, slaves were brought out from Africa and plantations were established along the more disease-free rivers. Exports of sugar, hardwood, Cayenne pepper and other spices brought a certain prosperity to the colony for the first time. Cayenne, the capital, was surrounded by plantations, some of which had several thousand slaves.

1800s and the Penal Era

In 1809 an Anglo-Portuguese naval squadron took French Guiana (ousting governor Victor Hugues) and gave it to the Portuguese in Brazil. However, with the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1814 the region was handed back to the French, though a Portuguese presence remained until 1817.

In 1848 France abolished slavery and the ex-slaves fled into the rainforest, setting up communities similar to the ones they had come from in Africa. Subsequently called Maroons, they formed a sort of buffer zone between the Europeans (who settled along the coast and main rivers) and the unconquered (and often hostile) Native American tribes of the inland regions. Deprived of slave labour the plantations were soon taken over by the jungle, and the planters ruined.

In 1850 several shiploads of Indians, Malays and Chinese were brought out to work the plantations but, instead, they set up shops in Cayenne and other settlements.

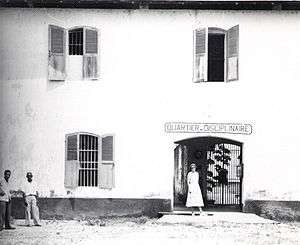

In 1852 the first shiploads of chained convicts arrived from France. In 1885, to get rid of habitual criminals and to increase the number of colonists, the French Parliament passed a law that anyone, male or female, who had more than three sentences for theft of more than three months each, would be sent to French Guiana as a relégué. These relégués were to be kept in prison there for six months but then freed to become settlers in the colony. However, this experiment failed dismally. The ex-prisoners, unable to make a living off the land found themselves forced to revert to crime or to eke out a hand-to-mouth existence until they died. In fact, transportation to French Guiana as a relégué amounted to a life sentence, and usually a short life sentence, as most of the relégués died very quickly from disease and malnutrition.

The prisoners would arrive at St Laurent du Maroni before being transported to various camps throughout the country. The Iles du Salut were used to house political prisoners and for solitary confinement. The islands became notorious for the brutality of life there, centering on the notorious Devil's Island. Famous figures sent to the islands included Alfred Dreyfus (in 1895) and Henri Charrière (in the 1930s). Charrière managed to escape and later wrote a best-selling book about his experiences called Papillon.

In 1853, gold was discovered in the interior, precipitating border disputes with Brazil and Suriname (these were later settled in 1891, 1899 and 1915, although a small region of the border with Suriname remains in dispute). The Republic of Independent Guyana, in French La République de la Guyane indépendante and commonly referred to by the name of the capital "Counani", was created in the area which was disputed by France (as part of French Guiana) and Brazil in the late nineteenth century.[6]

20th century

The territory of Inini, consisting of most of the interior of French Guiana, was created in 1930. It was abolished in 1946.

During World War II the local government declared its allegiance to the Vichy government, despite widespread support for Charles de Gaulle. This government was removed on 22 March 1943.

On January 12, 1943 a Jewish family of seven was deported on the German ship SS Cap Arcona headed toward Italy. The family ended up at Auschwitz II concentration camp. One member of the family died in crematorium 2.[7]

French Guiana became an overseas département of France on 19 March 1946.

The infamous penal colonies, including Devil's Island, were gradually phased out and then formally closed in 1951. At first, only those freed prisoners who could raise the fare for their return passage to France were able to go home, so French Guiana was haunted after the official closing of the prisons by numerous freed convicts leading an aimless existence in the colony.

Visitors to the site in December 1954 reported being deeply shocked by the conditions and the constant screams from the cell-block still in use for convicts who had gone insane and which had only tiny ventilation slots at the tops of the walls under the roof. Food was pushed in and bodies removed once a day.

In 1964 Kourou was chosen to be launch site for rockets, largely due to its favourable location near the equator. The Guiana Space Centre was built and became operational in 1968. This has provided some local employment and the mainly foreign technicians, and hundreds of troops stationed in the region to prevent sabotage, bring a little income to the local economy.

The 1970s saw the settlement of Hmong refugees from Laos in the county, primarily to the towns of Javouhey and Cacao. The Green Plan (Le Plan Vert) of 1976 aimed to improve production, though it had only limited success. A movement for increased autonomy from France gained momentum in the 70s and 80s, along with the increasing success of the Parti Socialiste Guyanais.

Protests by those calling for more autonomy from France have become increasingly vocal. Protests in 1996, 1997 and 2000 all ended in violence. While many Guianese wish to see more autonomy, support for complete independence is low.[8]

21st century

In a 2010 referendum, French Guianans voted against autonomy.[9]

On March 20, 2017, French Guianans began going on strike and demonstrating for more resources and infrastructure.[10] March 28, 2017 saw the largest demonstration ever held in French Guiana.[11]

Notes

- "French Guiana Time Line Chronological Timetable of Events - Worldatlas.com". www.worldatlas.com. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

- Gallois L. (1825) Biographie de tous les ministres: depuis la constitution de 1791, jusqu'au notre jours

- "Jean Samuel Guisan (1740–1801)". Helvetische Strassen-enquête (in German). Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- "French Revolution". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Sue Peabody, French Emancipation https://www.oxfordbibliographies.com/view/document/obo-9780199730414/obo-9780199730414-0253.xml Accessed 27 October 2019.

- "BIU Santé - Recherche dans les périodiques Medic@ - Map of area disputed between France and Brazil". Web2.bium.univ-paris5.fr. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- "22 Mar 1943 - FRENCH GUINEA TURNS FROM GIRAUD TO DE GAULLE NEW". Trove.nla.gov.au. 22 March 1943. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- The World Today Series: 2012 ISBN 978-1-610-48888-4 p. 395

- Faget, Dominique (3 April 2017). "Cazeneuve calls for continuation of dialogue in French Guiana". Radio France International. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

In a referendum in January 2010, French Guiana voted firmly against autonomy.

- Marot, Laurent (27 March 2017). "La Guyane paralysée par les mouvements sociaux". Le Monde. Retrieved 3 April 2017.

- "Guyane : manifestations historiques pour la "journée morte"". Le Point. 28 March 2017. Retrieved 4 April 2017.

References

- Belbenoit, René. 1940. Hell on Trial. Translated from the Original French Manuscript by Preston Rambo. E. P Dutton & Co. Reprint by Blue Ribbon Books, New York, 1941.

- Belbenoit, René. 1938. Dry Guillotine: Fifteen years among the living dead. Reprint: Berkley (1975). ISBN 0-425-02950-6. Reprint: Bantam Books, 1971.

- Charrière, Henri. Papillon. Reprints: Hart-Davis Macgibbon Ltd. 1970. ISBN 0-246-63987-3 (hbk); Perennial, 2001. ISBN 0-06-093479-4

- Tissot, Jean-Michel: La Guyane telle quelle, Paris (Le Créations du Pélican) 1998. ISBN 2-7191-0379-9

Further reading

- Kurlansky, Mark. 1992. A Continent of Islands: Searching for the Caribbean Destiny. Addison-Wesley Publishing. ISBN 0-201-52396-5.

External links

- History of French Guiana – History from the European Space Agency.