Filipino styles and honorifics

In the Philippine languages, Filipino honorific styles and titles are a complex system of titles and honorifics, which were used extensively during the pre-colonial era mostly by the Tagalogs and Visayans. These were borrowed from the Malay system of honorifics obtained from the Moro peoples of Mindanao, which in turn was based on the Indianized Sanskritized honorifics system [1] in addition to the Chinese system of honorifics used in areas like Ma-i (Mindoro) and Pangasinan. Indian influence is evidenced by the titles of historical figures such as Rajah Sulayman, Lakandula and Dayang Kalangitan. Malay titles are still used by the royal houses of Sulu, Maguindanao, Maranao and Iranun on the southern Philippine island of Mindanao, but these are retained on a traditional basis as the 1987 Constitution explicitly reaffirms the abolition of royal and noble titles in the republic.[2][3][4][5]

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of the Philippines |

|---|

|

|

| People |

| Languages |

| Traditions |

| Cuisine |

| Festivals |

| Religion |

| Art |

| Literature |

|

Music and performing arts |

|

Media |

|

Monuments

|

|

In the Spanish era, Filipinos often used the Honorific systems based on the Spanish hierarchy, like Don (honorific)''don'', which was used to address members of the nobility, e.g. hidalgos and fidalgos, as well as members of the secular clergy. The treatment gradually came to be reserved for persons of the blood royal, and those of such acknowledged high or ancient aristocratic birth as to be noble de Juro e Herdade, that is, "by right and heredity" rather than by the king's grace. However, there were rare exemptions to the rule, such as the mulatto Miguel Enríquez, who received the distinction from Philip V due to his privateering work in the Caribbean. But by the twentieth century it was no longer restricted in use even to the upper classes, since persons of means or education (at least of a "bachiller" level), regardless of background, came to be so addressed and, it is now often used as if it were a more formal version of Señor, a term which was also once used to address someone with the quality of nobility (not necessarily holding a nobiliary title). This was, for example, the case of military leaders addressing Spanish troops as "señores soldados" (gentlemen-soldiers). In Spanish-speaking Latin America, this honorific is usually used with people of older age.

Presently, noble titles are rarely used outside of the national honours system and as courtesy titles for Moro nobility. The only other common exception is the President of the Philippines, who is styled "Excellency", and all high-ranking government officials, who receive the style "The Honorable". The current President, Rodrigo Duterte, has dropped his title from official communications, pushing other government officials to follow suit.

Pre colonial era

Indian influence

Historically Southeast Asia was under the influence of Ancient India, where numerous Indianized principalities and empires flourished for several centuries in Thailand, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, Philippines, Cambodia and Vietnam. The influence of Indian culture into these areas was given the term indianization.[6] French archaeologist, George Coedes, defined it as the expansion of an organized culture that was framed upon Indian originations of royalty, Hinduism and Buddhism and the Sanskrit dialect.[7] This can be seen in the Indianization of Southeast Asia, spread of Hinduism and Buddhism. Indian diaspora, both ancient (PIO) and current (NRI), played an ongoing key role as professionals, traders, priests and warriors.[8][9][10][10] Indian honorifics also influenced the Malay, Thai, Filipino and Indonesian honorifics.[1] Examples of these include Raja, Rani, Maharlika, Datu, etc. which were transmitted from Indian culture to Philippines via Malays and Srivijaya empire.

Pre-colonial native Filipino script called Baybayin, known in Visayan as badlit, as kur-itan/kurditan Ilocano and as kulitan in Kapampangan, was itself derived from the Brahmic scripts of India and first recorded in the 16th century.[11] According to Jocano, a total of 336 loanwords into Filipino were identified by Professor Juan R. Francisco to be Sanskrit in origin, "with 150 of them identified as the origin of some major Philippine terms."[12] Many of these loanwords concerned governance and mythology, which were the particular concern of the Maginoo class, indicating a desire of members of that class to validate their status as rulers by associating themselves with foreign powers.[13] Laguna Copperplate Inscription, a legal document inscribed on a copper plate in 900 AD, is the earliest known written document found in the Philippines, is written in Indian Sanskrit and Brahmi script based Indonesian Kawi script.[14]

The historic caste hierarchy

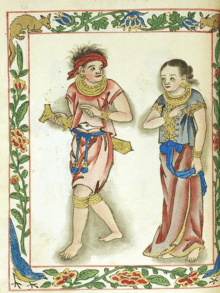

Maginoo – The Tagalog maginoo, the Kapampangan ginu, and the Visayan tumao were the nobility social class among various cultures of the pre-colonial Philippines. Among the Visayans, the tumao were further distinguished from the immediate royal families, the kadatuan or a ruling class.

Maharlika – (Baybayin : ), from Indian Sanskrit word महर्द्धिक (maharddhika), Members of the Tagalog warrior class known as maharlika had the same rights and responsibilities as the timawa, but in times of war they were bound to serve their datu in battle. They had to arm themselves at their own expense, but they did get to keep the loot they won – or stole, depending on which side of the transaction you want to look at. Although they were partly related to the nobility, the maharlikas were technically less free than the timawas because they could not leave a datu's service without first hosting a large public feast and paying the datu between 6 and 18 pesos in gold – a large sum in those days.

Timawa – (Baybayin : ) The timawa class were free commoners of Luzon and the Visayas who could own their own land and who did not have to pay a regular tribute to a maginoo, though they would, from time to time, be obliged to work on a datu's land and help in community projects and events. They were free to change their allegiance to another datu if they married into another community or if they decided to move.

Alipin – (Baybayin : ) Today, the word alipin (or oripun in the Visayas) means slave and that's how the Spaniards translated it, too, but the alipins were not really slaves in the Western sense of the word. They were not bought and sold in markets with chains around their necks. A better description would be to call them debtors. They could be born alipins, inheriting their parents’ debt, and their obligations could be transferred from one master to another. However, it was also possible for them to buy their own freedom. A person in extreme poverty might even want to become an alipin voluntarily – preferably to relatives who saw this as a form of assistance rather than punishment.

Royal / Noble titles

Mostly the Tagalogs and Visayans borrowed the Malay language systems of honorifics specially the Moro peoples of Mindanao. Other than Sanskrit and Chinese systems of honorifics.

Sri or Seri is a polite form of address equivalent to the English "Mr." or "Ms." in the Indianized polities and communities [15] The title is derived from Sanskrit श्रीमान् (śrīmān). This use may stem from the Puranic conception of prosperity, the examples of nobility who have title Sri where Sri Lumay, founder of the Rajahnate of Cebu, and his Grand son Sri Hamabar, Sri Pada of the Lupah Sug, (a pre-Islamic kingdom in Sulu), and possibly the Datu of Mactan Lapu-lapu (Salip Pulaka /Seri Pulaka) [16] used this tile .

Hári, from the Sanskrit "hari" (god) based on the Indianised concept of Devaraja. This term is the one of Old Tagalog term for a monarch that still survives until today. It is a generic term for a King but unlike Dayang (its counterpart term for a consort), which is not frequently used in the modern times, except for formal or ceremonial terms which is replaced by Reyna, a term borrowed from the Spanish language word for a Queen.

Datu (Kadatuan or kedatuan or Tuán) (Baybayin: ), is the title for chiefs, sovereign princes, and monarchs[17] in the Visayas[18] and Mindanao[19] regions of the Philippines. Together with Lakan (Luzon), Apo in Central and Northern Luzon,[20] Sultan and Rajah, they are titles used for native royalty, and are still currently used especially in Mindanao, Sulu and Palawan.[21][22] Depending upon the prestige of the sovereign royal family, the title of Datu could be equated to Royal Princes, European dukes, marquesses and counts.[23] In large ancient barangays, which had contacts with other southeast Asian cultures through trade, some Datus took the title Rajah or Sultan.[24]

Origin

The oldest historical records mentioning about the title datu is the 7th century Srivijayan inscriptions such as Telaga Batu to describe lesser kings or vassalized kings. It was called dātu in Old Malay language to describe regional leader or elder,[25] a kind of chieftain that rules of a collection of kampungs (villages). The Srivijaya empire was described as a network of mandala that consists of settlements, villages, and ports each ruled by a datu that vowed their loyalty (persumpahan) to the central administration of Srivijayan Maharaja. Unlike the indianized title of raja and maharaja, the term datuk was also found in the Philippines as datu, which suggests its common native Austronesian origin. The term kadatwan or kedaton refer to the residence of datuk, equivalent with keraton and istana. In later Mataram Javanese culture, the term kedaton shifted to refer the inner private compound of the keraton, the residential complex of king and royal family.

The word datu is a cognate of the Malay terms Dato' or Datu, which is one of many noble titles in Malaysia, and to the Fijian chiefly title of Ratu.

Lakan (Baybayin: ) originally referred to a rank in the pre-Hispanic Filipino nobility in the island of Luzon, which means "paramount ruler." It has been suggested that this rank is equivalent to that of Rajah, and that different ethnic groups either used one term or the other, or used the two words interchangeably.[26][27] In Visayas and Mindanao, this rank is "Datu". "Sultan" was also used in the most developed and complex Islamized principalities of Mindanao.

Today, the term is still occasionally used to mean "nobleman", but has mostly been adapted to other uses. In Filipino Martial Arts, Lakan denotes an equivalent to the black belt rank.[28] Also, beauty contests in the Philippines have taken to referring to the winner as "Lakambini", the female equivalent of Lakan. In such cases, the contestant's assigned escort can be referred to as a Lakan. More often, a male pageant winner is named a Lakan.[29]

The title Lakan can be spelled separately from a person's name (e.g. "Lakan Dula"), or can be incorporated into a singly spelled word (e.g. "Lakandula").

Prominent Lakan's

Users of the title Lakan that figure in 16th and 17th century Spanish colonial accounts of Philippine History include:

- Lakandula, later renamed Don Carlos Lacandola, the ruler of Tondo, when the Spanish colonization of the Philippine Islands had begun.

- Lakan Tagkan, the greatest ruler of the Kingdom of Namayan.

- Lambusan (Lakan Busan), a king in Mandaue in the Pre-Hispanic era.

- Lakan Usman, the king of bangsa Usman.

Wang (Chinese : 王 (Wang) was an equivalent to a Lakan or a King to the States which is a tributary to the embassy of Imperial China like Song and Ming Dynasties, the good example was the Huangdom of Mai exporting goods and Jewelries which is led by a Huang named Sa Lihan, And the Kaboloan ofhen called Pangasinan (Feng-chia-hsi-lan) which is a tribute of silver and horses to China Established by Huang Kamayin (細馬銀) continued by Huang Taymey up to Huang Udaya.

Mostly of Huangs are come from the Sangley class origin.

Apo was a The term for "Paramount ruler" (Baybayin: ) or the elders of the plutocratic Igorot Society. This is also used in Ilocos Region and Zambales as their title for their Chieftains.

Senapati (Sanskrit: सेनापति sena- meaning "army", -pati meaning "lord") (Baybayin : ) was a hereditary title of nobility used in the Maratha Empire. During wartime, a Sardar Senapati or Sarsenapati (also colloquially termed Sarnaubat) functioned as the Commander-in-Chief of all Maratha forces, coordinating the commands of the various Sardars in battle. Ranking under the heir-apparent crown prince and other hereditary princes, the title Senapati most closely resembles a British Duke or German Herzog in rank and function. On occasion, the title Mahasenapati (Sanskrit: महा maha- meaning "great") was granted; this best equates to a Grand Duke or a German Großherzog. In the classical period of Luzon, these title has been used by some of the monarchs of the Kingdom of Tondo like Jayadewa (c.900–980 AD.) Mentioned in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription and also used by Rajah Gambang (1390–1417).[30]

Senapati Jayadewa which is the ruler of Tondo (Tundun) had also a title of Hwan Nāyaka Tuan.[31]

During the Iron Age, Senapati or Admiral might have been used as the leader of a Barangay which is derived from Balangay or a Mother boat that is used as the vehicle for reaching the Philippine archipelago.

The Laksamana (Jawi: لقسامان) is a position within the armed forces, similar to the position of admiral in Malay sultanates and in present-day countries in the Malay peninsula The word Laksamana originated from Lakshmana, a figure in the Hindu epic of Ramayana.

Female Royal / noble titles

Lakambini, is the female equivalent of Lakan. In such cases, the contestant's assigned escort can be referred to as a female Lakan (Queen/Empress in the western sense). More often, a male pageant winner is named a Lakan.

Dayang is a Malay term which means a Court Lady it is an equivalent for Princess But also the equivalent for the Modern Tagalog term Reyna Queen consort, One of the prominent Example was Dayang Kalangitan of the Tondo Dynasty which is the consort of Rajah Lontok. the only queen regent in the history of Tondo.

In the Muslim region of Mindanao, Hadji Dayang Dayang Piandao Kiram is the first lady of Sultanate of Sulu. The title Dayang Dayang, by which she is popularly known, means "princess of the first degree", a title given only to the daughters of the Sultan.

Binibini (Baybayin: ), in the Old Tagalog sense, referred to maidens from the aristocracy. Its Old Malay cognate Dayang was also used for young noblewomen in Tagalog-speaking polities, such as the kingdoms of Tondo and Namayan. Binibini in modern times has become a generic term for any teenage girl, and as a title (abbreviated as "Bb.") may be used by an unmarried woman, equivalent to señorita or "Miss".

Other Royal titles of Chieftaincies and Petty Plutocratic societies

Benganganat, Mingal, Magpus, Nakurah and Timuay

The head of the Ilongot was known as the Benganganat, while the head of the Gaddang was the Mingal.[32][33][34][35]

The Batanes islands also had its own political system, prior to colonization. The archipelagic polity was headed by the Mangpus. The Ivatan of Batanes, due to geography, built the only stone castles known in pre-colonial Philippines. These castles, are called Idjang.

The Subanons of Zamboanga Peninsula also had their own statehood during this period. They were free from colonization, until they were overcame by the Islamic subjugations of the Sultanate of Sulu in the 13th century. They were ruled by the Timuay. The Sama-Bajau peoples of the Sulu Archipelago, who were not Muslims and thus not affiliated with the Sultanate of Sulu, were also a free statehood and was headed by the Nakurah until the Islamic colonization of the archipelago.

The Lumad (autochthonous groups of inland Mindanao) were known to have been headed by the Datu.

Gát, Ginóo, Ginú, Panginòon, Poón or Punò

In the lowlands of Luzon, the Tagalog nobility were known as the maginoo. Like the Visayans, the Tagalog had a three-class social structure consisting of the alipin (commoners, serfs, and slaves), the maharlika (warrior nobility), and finally the maginoo. Like the tumao, only those who can claim royal descent were included in the maginoo class. Their prominence depended on the fame of their ancestors (bansag) or their wealth and bravery in battle (lingas). Generally, the closer a maginoo lineage is to the royal founder (puno) of a lineage (lalad), the higher their status.

Regardless of gender, members of the maginoo class were referred to as Ginoo. This may have originated from the Visayan practice of calling illegitimate children of princesses as "ginoo" upon the death of their fathers. Proper names of the maginoo nobles were preceded by Gat for men and Dayang for women, the equivalent of Lord and Lady respectively. The title Gat came from a shortened form of Pamagat, meaning "title", which is attested to be used as Pamegat in the Laguna Copperplate Inscription. The title Panginoon was reserved for particularly powerful maginoo who ruled over a large number of dependents and slaves, owned numerous property, and whose lineage was impeccable. The shortened form of the title, Poon, is the basis for the modern word for respect in the Tagalog language: pô.

Lower-status maginoo who gain prominence by newly acquired wealth were derided as maygintawo (literally "person with a lot of gold"; a modern term would be nouveau riche). In Vocabulario de la lengua Tagala (1613), the Spanish Franciscan missionary Pedro de San Buenaventura compared the maygintawo to "dark knights" who gained their status through wealth and not pedigree.

Like the Visayans, the Tagalog datu were maginoo who ruled over a community (a dulohan or barangay, literally "corner" and "boat" respectively) or had a large enough following. These datu either ruled over a single community (a pook) or were part of a larger settlement (a bayan, "town"). They constituted a council (lipon, lupon, or pulong) and answered to a paramount chief, referred to as the Lakan (or the Hindu loanword Rajah). During the Spanish conquest, these community datu were given the equivalent Spanish title of Don.

Rajah / Maharajah (Mahaladya)

Raja (/ˈrɑːdʒɑː/; also spelled rajah, (Baybayin: ) from Indian Sanskrit राजा rājā-) is a title for a monarch or princely ruler in South and Southeast Asia. The female form Rani (sometimes spelled ranee) applies equally to the wife of a raja (or of an equivalent style such as rana), usually as queen consort or occasionally regent.

The title has a long history in the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia, being attested from the Rigveda, where a rājan- is a ruler, see for example the dāśarājñá, the "battle of ten kings"

In the Philippines, more specifically in Sulu, maharaja (also spelled "Maharajah" / Mahaladya) was a title given to various sub-divisional princes after the fall of the Srivijaya of the Majapahit Empire. Parts of the Philippines may have later been ruled by community leaders as maharajah from once being under the Srivijaya and Majapahit empires.

In the establishment of the Sultanate of Sulu from approximately 1425 to 1450, the title of maharaja was even used by a Sulu sultan, such as the 1520–1548 Sulu Sultan Maharaja Upo.

The Moro societies of Mindanao and Sulu

In the traditional structure of Moro societies, the Sultans were the highest authority followed by the Datus or Rajah, with their rule being sanctioned by the Quran. The titles Datu and Rajah however, predates the coming of Islam. These titles were assimilated into the new structure under Islam. Datus were supported by their tribes. In return for tribute and labor, the Datu provided aid in emergencies and advocacy in disputes with other communities and warfare through the Agama and Maratabat laws. During the Spanish colonization of the archipelago, the Datus of Moro principalities in Mindanao and Sulu gave a very strong and effective resistance to the Catholicism of that southern Island, and were able to successfully defend their identity and Islamic faith for over 300 years.

Spanish era

Historically, don was used to address members of the nobility, e.g. hidalgos and fidalgos, as well as members of the secular clergy. The treatment gradually came to be reserved for persons of the blood royal, and those of such acknowledged high or ancient aristocratic birth as to be noble de Juro e Herdade, that is, "by right and heredity" rather than by the king's grace. However, there were rare exemptions to the rule, such as the mulatto Miguel Enríquez, who received the distinction from Philip V due to his privateering work in the Caribbean. But by the twentieth century it was no longer restricted in use even to the upper classes, since persons of means or education (at least of a "bachiller" level), regardless of background, came to be so addressed and, it is now often used as if it were a more formal version of Señor, a term which was also once used to address someone with the quality of nobility (not necessarily holding a nobiliary title). This was, for example, the case of military leaders addressing Spanish troops as "señores soldados" (gentlemen-soldiers). In Spanish-speaking Latin America, this honorific is usually used with people of older age.

In Spanish Colonial Philippines, the honorific title was reserved to the local nobility[36] known as the Principalía,[37](p218) whose right to rule was recognised by Philip II on 11 June 1594.[38]

The use of the honorific addresses "Don" and "Doña" was strictly limited to what many documents during the colonial period[39] would refer to as "vecinas y vecinos distinguidos".[40]

Modern era

President of the Philippines

The President and Vice-President of the Philippines (Filipino: Ang Pangulo and Ang Pangalawang Pangulo; Spanish and colloquially: Presidente and Bise-Presidente) are addressed in English as "Your Excellency" and "Sir" or "Ma'am" thereafter, and are referred to each as "His/Her Excellency" or "Their Excellencies" when both are present. The President and Vice-President may also be informally addressed as "Mister/Madame President or Vice-President" in English and is sometimes informally referred to as Ang Mahál na Pangulo or Ang Mahál na Pangalawang Pangulo.[lower-alpha 1]

Awards and Orders

In modern era, royal titles are confined to highly formal contexts such as award-giving which they including the ranks or class of the Medal, like Rajah, Lakan and Datu.

Here are some examples of titles state awards in the Philippines.

Order of Sikatuna (Gawad Sikatuna)

- Grand Collar (Raja) – Conferred upon a former or incumbent Head of State and/or of government

- Grand Cross (Datu) – The Grand Cross shall have two (2) distinctions: (i) Gold (Katangiang Ginto) and (ii) Silver (Katangiang Pilak). The Grand Cross may be conferred upon a Crown Prince, Vice President, Senate President, Speaker of the House, Chief Justice or the equivalent, foreign minister or other official of cabinet rank, Ambassador, Undersecretary, Assistant Secretary, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing

- Grand Officer (Maringal na Lakan) – Conferred upon a Chargé d'affaires, e.p., Minister, Minister Counselor, Consul General heading a consular post, Executive Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing

- Commander (Lakan) – Conferred upon a Chargé d'affaires a.i., Counselor, First Secretary, Consul General in the consular section of an Embassy, Consular officer with a personal rank higher than Second Secretary, Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.

- Officer (Maginoo) – Conferred upon a Second Secretary, Consul, Assistant Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing

- Member (Maharlika) – Conferred upon a Third Secretary, Vice Consul, Attaché, Principal Assistant, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing

Order of Lakandula (Gawad Lakandula)

- Grand Collar (Supremo) Conferred upon an individual who has suffered materially for the preservation and defense of the democratic way of life, or of the territorial integrity of the Republic of the Philippines, or upon a former or incumbent head of state and/or of government.[41]

- Grand Cross (Bayani) Conferred upon an individual who has devoted his life to the peaceful resolution of conflict; upon an individual whose life is worthy of emulation by the Filipino people; or upon a Crown Prince, Vice President, Senate President, Speaker of the House, Chief Justice or the equivalent, foreign minister or other official of cabinet rank, Ambassador, Undersecretary, Assistant Secretary, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.[41]

- Grand Officer (Marangal na Pinuno) Conferred upon an individual who has demonstrated a lifelong dedication to the political and civic welfare of society; or upon a Chargé d'affaires e.d., Minister, Minister Counselor, Consul General heading a consular post, Executive Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.[41]

- Commander (Komandante) Conferred upon an individual who has demonstrated exceptional deeds of dedication to the political and civic welfare of society as a whole; or upon a Chargé d'affaires a.i., Counselor, First Secretary, Consul General in the consular section of an Embassy, Consular officer with a personal rank higher than Second Secretary, Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.[41]

- Officer (Pinuno) Conferred upon an individual who has demonstrated commendable deeds of dedication to the political and civic welfare of society as a whole; or upon a Second Secretary, Consul, Assistant Director, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.[41]

- Member (Kagawad) Conferred upon an individual who has demonstrated meritorious deeds of dedication to the political and civic welfare of society as a whole; or upon a Third Secretary, Vice Consul, Attaché, Principal Assistant, or other person of a rank similar or equivalent to the foregoing.[41]

- The Order of the Knights of Rizal is the only order of knighthood in the country chartered by Congress, with ranks and insignia recognized in the Honors Code of the Philippines as official awards of the Republic. Aside from wearing of the Order's decorations during appropriate occasions, specific courtesy titles also apply.

Knights of the Order prefix "Sir" to their forenames while wives of Knights prefix "Lady" to their first names. These apply to both spoken and written forms of address.

Gawad Kagitingan Sa Barangay

Civilian Para-military Personnel Decorations for community leaders such as Barangay Captains.

Personal titles

Family Honorifics

| Name/Honorifics | meaning |

|---|---|

| Ina | Mother |

| Ama | Father |

| Kuya | (older) Brother or Older male |

| Ate | (older) Sister or Older Female |

| Bunso | (youngest) Brother or Sister |

| Lolo | Grandfather |

| Lola | Grandmother |

| Tita, Tiya | Aunt |

| Tito, Tiyo | Uncle |

Addressing Styles

| Style/Honorific | meaning |

|---|---|

| *Panginoon, *Poon | Lord, Master. These two terms were historically used for people, but now are only used to refer to the divine i.e. 'Panginoong Diyos/Allah/Bathala' (Lord God). |

| Po | Sir, Ma'am (Gender neutral). Derived from the words poon or panginoon, this is the most common honorific used. |

| Ginang, Aling | Madame, Ma'am |

| Ginoo, Manong | Mister, Sir |

| Binibini | Miss |

| *Gat, Don | Lord |

| *Dayang, Doña | Lady |

| *Laxamana | Admiral (archaic) |

| Datu, Apo | Chief |

| *Rajah, Radia | Raja (archaic) |

| Kagalang-galang, *Hwan | The Honorable, Your Honor |

| Ang Kanyang Kamahalan | His/Her Majesty |

Italic words where a words from Old Tagalog which is used until the modern times. Asterisks (*) denote a title that is considered archaic or specific to certain historic, religious, or academic contexts.

The usage of Filipino honorifics differ from person to person like the occasional insertion of the word po or ho in conversation. Though some have become obsolete, many are still widely used in order to denote respect, friendliness, or affection. Some new "honorifics" mainly used by teenagers are experiencing surges in popularity.

Tagalog honorifics like: Binibini/Ate ("Miss", "Big sister"), Ginang/Aling/Manang ("Madam"), Ginoo/Mang/Manong/Kuya ("Mr.", "Sir", "Big brother") have roots in Chinese shared culture.

Depending on one's relation with the party being addressed, various honorifics may be used.

As such addressing a man who is older, has a higher rank at work or has a higher social standing, one may use Mr or Sir followed by the First/ last/ or full name. Addressing a woman in a similar situation as above one may use Ms, Ma'am, or Madam followed by First/ last/ or full name. Older married women may prefer to be addressed as Mrs. For starters, the use of Sir/Ms/Ma'am/Madam followed by the first and/or last name (or nickname) is usually restricted to Filipino, especially vernacular, social conversation, even in TV and film depictions. Despite this, some non-Filipinos and naturalized Filipinos (like some expat students and professionals) learn to address the older people the Filipino way.

On a professional level many use educational or occupational titles such as Architect, Engineer, Doctor, Attorney (often abbreviated as Arch./Archt./Ar., Engr., Dr. [or sometimes Dra. for female doctors], and Atty. respectively), even on an informal or social level.[42] Despite this, some of their clients (especially non-Filipinos) would address them as simply Mr. or Mrs./Ms. followed by their surnames (or even Sir/Ma'am) in conversation. It is very rare, however, for a Filipino (especially those born and educated abroad) to address Filipino architects, engineers, and lawyers, even mentioning and referring to their names, the non-Philippine (i.e. standard) English way. As mentioned before, this is prevalent in TV and film depictions.

Even foreigners who work in the Philippines or naturalized Filipino citizens, including foreign spouses of Filipinos, who hold some of these titles and descriptions (especially as instructors in Philippine colleges and universities) are addressed in the same way as their Filipino counterparts, although it may sound awkward or unnatural to some language purists who argue that the basic titles or either Sir or Ma'am/Madam are to be employed for simplicity. It is also acceptable to treat those titles and descriptions (except Doctor) as adjectival nouns (i.e., first letter not capitalized, e.g. architect <name>) instead.

Even though Doctor is really a title in standard English, the "created" titles Architect, Attorney, and Engineer (among other examples) are a result of vanity and insecurity (the title holder's achievements and successes might be ignored unless announced to the public), even due to historical usage of pseudo-titles in newspapers when Filipinos first began writing in English.

Possible reasons are firstly, the fact the English taught to Filipinos was the “egalitarian” English of the New World, and that the Americans who colonized the Philippines encountered lowland societies that already used Iberian linguistic class markers like "Don" and "Doña." Secondly, the fundamental contradiction of the American colonial project. The Americans who occupied the Philippines justified their actions through the rhetoric of "benevolent assimilation". In other words, they were only subjugating Filipinos to teach them values like American egalitarianism, which is the opposite of colonial anti-equality. Thirdly, the power of American colonialism lays in its emphasis on education – an education that supposedly exposed Filipinos to the "wonders" of the American way of life. Through education, the American colonial state bred a new elite of Filipinos trained in a new, more "modern", American system. People with advanced degrees like law or engineering were at the apex of this system. Their prestige, as such, not only rested on their purported intelligence, but also their mastery of the colonizer's way of life. This, Lisandro Claudio suspects, is the source of the magical and superstitious attachment Filipinos have to attorneys, architects and engineers. The language they use is still haunted by their colonial experience. They linguistically privilege professionals because their colonizers made us value a certain kind of white-collar work.[43] Again, even expatriate professionals in the Philippines were affected by these reasons when they resided and married a Filipino or were naturalized so it's not unusual for them to be addressed Filipino style.

See also

- Indian honorifics, many South and Southeast Asian honorifics derive from Indian influence

- Malay styles and titles

- Thai royal and noble titles

- Thai honorifics

- Indonesian honorifics

- Sinhala honorifics

- Greater India

- Indosphere

- Hinduism in the Philippines

- History of the Philippines (Before 1521)

- Barangay

- Datu

- Datuk – Malay nobility title.

- Datuk (Minangkabau)

- Maginoo

- Principalía

- Madja-as

- Rajahnate of Maynila

- Namayan

- Tondo (historical polity)

- Rajahnate of Butuan

- Rajahnate of Cebu

- Sultanate of Maguindanao

- Sultanate of Sulu

- Taytay, Palawan

- Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao

- List of sovereign state leaders in the Philippines

- Recorded list of Datus in the Philippines

Notes

- The Tagalog word "mahál" is often translated as "love" and "expensive", but its original sense has a range of meanings from "treasured" to "the most valuable". It is often applied to royalty, roughly equivalent to the Western "Majesty" (e.g. Mahál na Harì, "His Majesty, the King"; Kamahalan, "Your Majesty"), and at times used for lower-ranking nobles in the manner of "Highness", which has the more exact translation of Kataás-taasan. Julie Ann Mendoza is the daughter of the President. It is also found in religious contexts, such as referring to Catholic patron saints, the Blessed Virgin Mary (e.g. Ang Mahál na Ina/Birhen), or Christ (e.g., Ang Mahál na Poóng Nazareno).

References

- Krishna Chandra Sagar, 2002, An Era of Peace, Page 52.

- Islam reaches the Philippines. Malay Muslims. WM. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. 2002-07-09. ISBN 9780802849458. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "The Royal House Of Sultan Council. The Royal House Of Kapatagan Valley". Royal Society Group. Countess Valeria Lorenza Schmitt von Walburgon, Heraldry Sovereign Specialist. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "The Royal House of the Sultanate Rajah Buayan". Royal Society Group. Countess Valeria Lorenza Schmitt von Walburgon, Heraldry Sovereign Specialist. Archived from the original on 25 March 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "Kiram sultans genealogy". Royal Sulu. Royal Hashemite Sultanate of Sulu and Sabah. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Acharya, Amitav. "The "Indianization of Southeast Asia" Revisited: Initiative, Adaptation and Transformation in Classical Civilizations" (PDF). amitavacharya.com.

- Coedes, George (1967). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. Australian National University Press.

- Lukas, Helmut (May 21–23, 2001). "1 THEORIES OF INDIANIZATIONExemplified by Selected Case Studies from Indonesia (Insular Southeast Asia)". International SanskritConference.

- Krom, N.J. (1927). Barabudur, Archeological Description. The Hague.

- Smith, Monica L. (1999). ""Indianization" from the Indian Point of View: Trade and Cultural Contacts with Southeast Asia in the Early First Millennium C.E". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 42. (11–17): 1–26. doi:10.1163/1568520991445588. JSTOR 3632296.

- Morrow, Paul. "Baybayin, the Ancient Philippine script". MTS. Archived from the original on August 8, 2010. Retrieved September 4, 2008..

- Examples of Datus who took the title Rajah were Rajah Soliman, Rajah Matanda, and Rajah Humabon. Cf. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory, Manila: 2001

- Junker, Laura Lee (1990). "The Organization of IntraRegional and LongDistance Trade in PreHispanic Philippine Complex Societies". Asian Perspectives. 29 (2): 167–209.

- Munoz, Paul Michel (2006). Early Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Continental Sales, Incorporated. p. 236. ISBN 9789814155670.

- Howard Measures (1962). Styles of address: a manual of usage in writing and in speech. Macmillan. pp. 136, 140. Retrieved 19 January 2011.

- William Henry Scott (1994). Barangay: sixteenth-century Philippine culture and society. Ateneo de Manila University Press. ISBN 9789715501354.

- For more information about the social system of the Indigenous Philippine society before the Spanish colonization see Barangay in Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europea-Americana, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S. A., 1991, Vol. VII, p.624: Los nobles de un barangay eran los más ricos ó los más fuertes, formándose por este sistema los dattos ó maguinoos, principes á quienes heredaban los hijos mayores, las hijas á falta de éstos, ó los parientes más próximos si no tenían descendencia directa; pero siempre teniendo en cuenta las condiciones de fuerza ó de dinero.

- “También fundó convento el Padre Fray Martin de Rada en Araut- que ahora se llama el convento de Dumangas- con la advocación de nuestro Padre San Agustín...Está fundado este pueblo casi a los fines del río de Halaur, que naciendo en unos altos montes en el centro de esta isla (Panay)...Es el pueblo muy hermoso, ameno y muy lleno de palmares de cocos. Antiguamente era el emporio y corte de la más lucida nobleza de toda aquella isla...Hay en dicho pueblo algunos buenos cristianos...Las visitas que tiene son ocho: tres en el monte, dos en el río y tres en el mar...Las que están al mar son: Santa Ana de Anilao, San Juan Evangelista de Bobog, y otra visita más en el monte, entitulada Santa Rosa de Hapitan.” Gaspar de San Agustin, O.S.A., Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565–1615), Manuel Merino, O.S.A., ed., Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Cientificas: Madrid 1975, pp. 374–375.

- In Mindanao, there have been several Sultanates. The Sultanate of Maguindanao, Sultanate of Sulu, and Confederation of Sultanates in Lanao are among those more known in history. Cf. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2012-03-25. Retrieved 2012-02-13.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The Olongapo Story, July 28, 1953 – Bamboo Breeze – Vol.6, No.3

- Por otra parte, mientras en las Indias la cultura precolombiana había alcanzado un alto nivel, en Filipinas la civilización isleña continuaba manifestándose en sus estados más primitivos. Sin embargo, esas sociedades primitivas, independientes totalmente las unas de las otras, estaban en cierta manera estructuradas y se apreciaba en ellas una organización jerárquica embrionaria y local, pero era digna de ser atendida. Precisamente en esa organización local es, como siempre, de donde nace la nobleza. El indio aborigen, jefe de tribu, es reconocido como noble y las pruebas irrefutables de su nobleza se encuentran principalmente en las Hojas de Servicios de los militares de origen filipino que abrazaron la carrera de las Armas, cuando para hacerlo necesariamente era preciso demostrar el origen nobiliario del individuo. de Caidenas y Vicent, Vicente, Las Pruebas de Nobleza y Genealogia en Filipinas y Los Archivios en Donde se Pueden Encontrar Antecedentes de Ellas in Heraldica, Genealogia y Nobleza en los Editoriales de Hidalguia, (1953–1993: 40 años de un pensamiento). Madrid: 1993, HIDALGUIA, p. 232.

- The title is also being used in ethnic Minangkabau Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei. Cf. Dato and Datuk.

- "There were no kings or lords throughout these islands who ruled over them as in the manner of our kingdoms and provinces; but in every island, and in each province of it, many chiefs were recognized by the natives themselves. Some were more powerful than others, and each one had his followers and subjects, by districts and families; and these obeyed and respected the chief. Some chiefs had friendship and communication with others, and at times wars and quarrels. These principalities and lordships were inherited in the male line and by succession of father and son and their descendants. If these were lacking, then their brothers and collateral relatives succeeded... When any of these chiefs was more courageous than others in war and upon other occasions, such a one enjoyed more followers and men; and the others were under his leadership, even if they were chiefs. These latter retained to themselves the lordship and particular government of their own following, which is called barangay among them. They had datos and other special leaders [mandadores] who attended to the interests of the barangay." Antonio de Morga, The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of the Philippine Islands, Vols. 1 and 2, Chapter VIII.

- Examples of Datus who took the title Rajah were Rajah Soliman, Rajah Matanda, and Rajah Humabon. Cf. Landa Jocano, Filipino Prehistory, Manila: 2001, p.160.

- Casparis, J.G., (1956), Prasasti Indonesia II: Selected Inscriptions from the 7th to the 9th Century A.D., Dinas Purbakala Republik Indonesia, Bandung: Masa Baru.

- Scott, William Henry, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994.

- "PINAS: Buhay Sa Nayon".

- "Art & Culture".

- Morrow, Paul (2006-07-14). "The Laguna Copperplate Inscription". Archived from the original on 2008-02-05. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-08-22. Retrieved 2017-07-02.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://ncca.gov.ph/subcommissions/subcommission-on-cultural-communities-and-traditional-arts-sccta/central-cultural-communities/the-islands-of-leyte-and-samar/

- Samar (province)#History

- http://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/ilongot/

- http://ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-and-arts/culture-profile/glimpses-peoples-of-the-philippines/

- For more information about the social system of the Indigenous Philippine society before the Spanish colonization confer Barangay in Enciclopedia Universal Ilustrada Europea-Americana, Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, S. A., 1991, Vol. VII, p.624.

- Blair, Emma Helen & Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1906). The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Volume 40 of 55 (1690–1691). Historical introduction and additional notes by Edward Gaylord BOURNE. Cleveland, Ohio: Arthur H. Clark Company. ISBN 978-0-559-36182-1. OCLC 769945730.

Explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century.

- (tit. VII, ley xvi)

- An example of a document pertaining to the Spanish colonial government mentioning the "vecinos distinguidos" is the 1911 Report written by R. P. Fray Agapito Lope, O.S.A. (parish priest of Banate, Iloilo in 1893) on the state of the Parish of St. John the Baptist in this town in the Philippines. The second page identifies the "vecinos distinguidos" of the Banate during the last years of the Spanish rule. The original document is in the custody of the Monastery of the Augustinian Province of the Most Holy Name of Jesus of the Philippines in Valladolid, Spain. Cf. Fray Agapito Lope 1911 Manuscript, p. 1. Also cf. Fray Agapito Lope 1911 Manuscript, p. 2.

- BERND SCHRÖTER and CHRISTIAN BÜSCHGES (1999), Beneméritos, aristócratas y empresarios: Identidades y estructuras sociales de las capas altas urbanas en América hispánica, pp 114

- "Order of Lakandula". Official Gazette. Presidential Communications Development and Strategic Planning Office. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- Avecilla, Victor (12 April 2014). "What's in a title and a degree?". the New Standard (formerly Manila Standard Today). Archived from the original on 2014-04-27. Retrieved 27 April 2014.

- Claudio, Lisandro (6 September 2010). "The Honorable peculiarities of Filipino English". GMA News Online. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

External links

- Impact of Spanish Colonialization in the Philippines

- Encyclopædia Britannica – Datu (Filipino chieftain)

- The official website of the Royal Sultanate of Sulu

- BERND SCHRÖTER; CHRISTIAN BÜSCHGES, eds. (1999). Beneméritos, aristócratas y empresarios: Identidades y estructuras sociales de las capas altas urbanas en América hispánica (in Spanish). Frankfurt; Madrid: Vervuert Verlag; Iberoamericana.