Diffuse interstellar bands

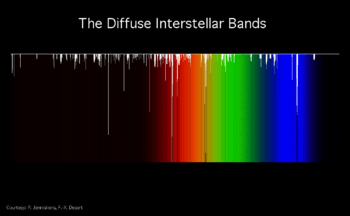

Diffuse interstellar bands (DIBs) are absorption features seen in the spectra of astronomical objects in the Milky Way and other galaxies. They are caused by the absorption of light by the interstellar medium. Circa 500 bands have now been seen, in ultraviolet, visible and infrared wavelengths.[1]

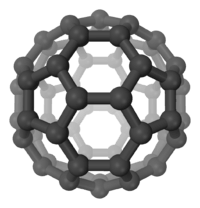

The origin of DIBs was unknown and disputed for many years, and the DIBs were long believed to be due to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and other large carbon-bearing molecules.[2][3] Their rapid and efficient deactivation when photoexcited accounts for their remarkable photostability[4][5] and therefore possible abundance in the interstellar medium. However, no agreement of the bands could be found with laboratory measurements or with theoretical calculations until July 2015, when the group of John Maier (University of Basel) announced the unequivocal assignment of two lines for Buckminsterfullerene (C60+),[6] confirming a prediction made in 1987.[7]

Discovery and history

Much astronomical work relies on the study of spectra - the light from astronomical objects dispersed using a prism or, more usually, a diffraction grating. A typical stellar spectrum will consist of a continuum, containing absorption lines, each of which is attributed to a particular atomic energy level transition in the atmosphere of the star.

The appearances of all astronomical objects are affected by extinction, the absorption and scattering of photons by the interstellar medium. Relevant to DIBs is interstellar absorption, which predominantly affects the whole spectrum in a continuous way, rather than causing absorption lines. In 1922, though, astronomer Mary Lea Heger[8] first observed a number of line-like absorption features which seemed to be interstellar in origin.

Their interstellar nature was shown by the fact that the strength of the observed absorption was roughly proportional to the extinction, and that in objects with widely differing radial velocities the absorption bands were not affected by Doppler shifting, implying that the absorption was not occurring in or around the object concerned.[9][10][11] The name Diffuse Interstellar Band, or DIB for short, was coined to reflect the fact that the absorption features are much broader than the normal absorption lines seen in stellar spectra.

The first DIBs observed were those at wavelengths 578.0 and 579.7 nanometers (visible light corresponds to a wavelength range of 400 - 700 nanometers). Other strong DIBs are seen at 628.4, 661.4 and 443.0 nm. The 443.0 nm DIB is particularly broad at about 1.2 nm across - typical intrinsic stellar absorption features are 0.1 nm or less across.

Later spectroscopic studies at higher spectral resolution and sensitivity revealed more and more DIBs; a catalogue of them in 1975 contained 25 known DIBs, and a decade later the number known had more than doubled. The first detection-limited survey was published by Peter Jenniskens and Xavier Desert in 1994 (see Figure above),[12] which led to the first conference on The Diffuse Interstellar Bands at the University of Colorado in Boulder on May 16–19, 1994. Today circa 500 have been detected.

In recent years, very high resolution spectrographs on the world's most powerful telescopes have been used to observe and analyse DIBs.[13] Spectral resolutions of 0.005 nm are now routine using instruments at observatories such as the European Southern Observatory at Cerro Paranal, Chile, and the Anglo-Australian Observatory in Australia, and at these high resolutions, many DIBs are found to contain considerable sub-structure.[14][15]

The nature of the carrier

The great problem with DIBs, apparent from the earliest observations, was that their central wavelengths did not correspond with any known spectral lines of any ion or molecule, and so the material which was responsible for the absorption could not be identified. A large number of theories were advanced as the number of known DIBs grew, and determining the nature of the absorbing material (the 'carrier') became a crucial problem in astrophysics.

One important observational result is that the strengths of most DIBs are not strongly correlated with each other. This means that there must be many carriers, rather than one carrier responsible for all DIBs. Also significant is that the strength of DIBs is broadly correlated with the interstellar extinction. Extinction is caused by interstellar dust; however, DIBs, are not likely to be caused by dust grains.

The existence of sub-structure in DIBs supports the idea that they are caused by molecules. Substructure results from band heads in the rotational band contour and from isotope substitution. In a molecule containing, say, three carbon atoms, some of the carbon will be in the form of the carbon-13 isotope, so that while most molecules will contain three carbon-12 atoms, some will contain two 12C atoms and one 13C atom, much less will contain one 12C and two 13C, and a very small fraction will contain three 13C molecules. Each of these forms of the molecule will create an absorption line at a slightly different rest wavelength.

The most likely candidate molecules for producing DIBs are thought to be large carbon-bearing molecules, which are common in the interstellar medium. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, long carbon-chain molecules such as polyynes, and fullerenes are all potentially important.[9][16]

Fullerene C60+ identified as carrier of diffuse interstellar bands

The first prediction that C60+ could be a carrier of DIBs was put forward by Harry Kroto,[17] co-discoverer of C60. In 1987, Kroto proposed that "The present observations indicate that C60 might survive in the general medium (probably as the ion C60+) protected by its unique ability to survive processes so drastic that most, if not all, other known molecules are destroyed."[18] However, that time it was hard to prove due to inability to record a reliable spectrum of C60+.[19]

Only in 2015, C60+ spectrum was obtained by the group of John Maier at the University of Basel.[20] They developed a state of the art spectroscopic technique that allowed observation of C60+ spectrum at the low temperature and low pressure comparable with interstellar medium. The precise overlap between diffused bands at 9632 Å and 9577 Å observed by Foing and Enhrenfreund in 1994 and spectroscopic bands of C60+ in helium matrix recorded in 2015, has confirmed C60+ as a first DIB carrier.[20] Later on, three other C60+ bands at 9428 Å, 9365 Å, and 9348 Å were found among near-infrared DIBs.[21] The presence of the 9365 Å, 9428 Å and 9577 Å C60+ bands was subsequently confirmed using the Hubble Space Telescope, towards a sample of seven Galactic background stars, which helped place the assignment of interstellar C60+ beyond reasonable doubt.[22]

The origin of closely spaced C60+ bands was not understood until 2018, when the quantum chemistry studies revealed the Jahn-Teller distortion of C60+ excited state. This distortion leads to the two excited states (Bg and Ag) populated upon light illumination. Two states form two progressions of closely spaced absorption bands. The strong bands at 9632 Å and 9577 Å were assigned to the cold electronic excitations, while the weak bands at 9428 Å, 9365 Å, and 9348 Å to the hot vibronic excitations.[23]

References

- "ESO Diffuse Interstellar Bands Large Exploration Survey (EDIBLES) - Merging Observations and Laboratory Data". 2016-03-29. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Bierbaum, Veronica M.; Keheyan, Yeghis; Page, Valery Le; Snow, Theodore P. (January 1998). "The interstellar chemistry of PAH cations". Nature. 391 (6664): 259–260. Bibcode:1998Natur.391..259S. doi:10.1038/34602. PMID 9440689.

- Snow, Theodore P. (2001-03-15). "The unidentified diffuse interstellar bands as evidence for large organic molecules in the interstellar medium". Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy. 57 (4): 615–626. Bibcode:2001AcSpA..57..615S. doi:10.1016/S1386-1425(00)00432-7. PMID 11345242.

- Zhao, Liang; Lian, Rui; Shkrob, Ilya A.; Crowell, Robert A.; Pommeret, Stanislas; Chronister, Eric L.; Liu, An Dong; Trifunac, Alexander D. (2004). "Ultrafast Studies on the Photophysics of Matrix-Isolated Radical Cations of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons". The Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 108 (1): 25–31. Bibcode:2004JPCA..108...25Z. doi:10.1021/jp021832h.

- Tokmachev, Andrei M.; Boggio-Pasqua, Martial; Mendive-Tapia, David; Bearpark, Michael J.; Robb, Michael A. (2010). "Fluorescence of the perylene radical cation and an inaccessible D0/D1 conical intersection: An MMVB, RASSCF, and TD-DFT computational study". The Journal of Chemical Physics. 132 (4): 044306. Bibcode:2010JChPh.132d4306T. doi:10.1063/1.3278545. PMID 20113032.

- Campbell, E. K.; Holz, M.; Gerlich, D.; Maier, J. P. (2015). "Laboratory confirmation of C60+ as the carrier of two diffuse interstellar bands". Nature. 523 (7560): 322–3. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..322C. doi:10.1038/nature14566. PMID 26178962.

- "C60 in space and the Diffuse Interstellar Bands - History and State of the Art". Retrieved 23 August 2015.

- Heger, M. L. (1922). "Further study of the sodium lines in class B stars". Lick Observatory Bulletin. 10 (337): 141–148. Bibcode:1922LicOB..10..141H. doi:10.5479/ADS/bib/1922LicOB.10.141H.

- Herbig, G. H. (1995). "The Diffuse Interstellar Bands". Annual Review of Astronomy and Astrophysics. 33: 19–73. Bibcode:1995ARA&A..33...19H. doi:10.1146/annurev.aa.33.090195.000315.

- Krelowski, J. (1989). "Diffuse interstellar bands - An observational review". Astronomische Nachrichten. 310 (4): 255–263. Bibcode:1989AN....310..255K. doi:10.1002/asna.2113100403.

- Sollerman, J.; et al. (2005). "Diffuse Interstellar Bands in NGC 1448". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 429 (2): 559–567. arXiv:astro-ph/0409340. Bibcode:2005A&A...429..559S. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20041465.

- Jenniskens, P.; Desert, F.-X. (1994). "A survey of diffuse interstellar bands (3800-8680 A)". Astronomy and Astrophysics Supplement Series. 106: 39. Bibcode:1994A&AS..106...39J.

- Fossey, S. J.; Crawford, I. A. (2000). "Observing with the Ultra-High-Resolution Facility at the Anglo-Australian Telescope: Structure of Diffuse Interstellar Bands". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 32: 727. Bibcode:2000AAS...196.3501F.

- Jenniskens, P.; Desert, F. X. (1993). "Complex Structure in Two Diffuse Interstellar Bands". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 274: 465. Bibcode:1993A&A...274..465J.

- Galazutdinov, G.; et al. (2002). "Fine structure of profiles of weak diffuse interstellar bands". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 396 (3): 987–991. Bibcode:2002A&A...396..987G. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20021299.

- Ehrenfreund, P. (1999). "The Diffuse Interstellar Bands as evidence for polyatomic molecules in the diffuse interstellar medium". Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society. 31: 880. Bibcode:1999AAS...194.4101E.

- "C60 in space and the diffuse interstellar bands".

- Kroto, H. W. (1987). "Chains and Grains in Interstellar Space" (PDF). Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons and Astrophysics. 191: 197–206. Bibcode:1987ASIC..191..197K.

- Fulara, Jan; Jakobi, Michael; Maier, John P. (1993-08-13). "Electronic and infrared spectra of C+60 and C−60 in neon and argon matrices". Chemical Physics Letters. 211 (2–3): 227–234. Bibcode:1993CPL...211..227F. doi:10.1016/0009-2614(93)85190-Y. ISSN 0009-2614.

- Maier, J. P.; Gerlich, D.; Holz, M.; Campbell, E. K. (July 2015). "Laboratory confirmation of C60+ as the carrier of two diffuse interstellar bands". Nature. 523 (7560): 322–323. Bibcode:2015Natur.523..322C. doi:10.1038/nature14566. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26178962.

- Campbell, E. K.; Holz, M.; Maier, J. P.; Gerlich, D.; Walker, G. A. H.; Bohlender, D. (2016). "Gas Phase Absorption Spectroscopy of C+60 and C+70 in a Cryogenic Ion Trap: Comparison with Astronomical Measurements". The Astrophysical Journal. 822 (1): 17. Bibcode:2016ApJ...822...17C. doi:10.3847/0004-637X/822/1/17. ISSN 0004-637X.

- Cordiner, M.; Linnartz, H.; Cox, N.; Cami, J.; Najarro, F.; Proffitt, C.; Lallement, R.; Ehrenfreund, P.; Foing, B.; Gull, T.; Sarre, P.; Charnley, S. (2019). "Confirming Interstellar C60+ Using the Hubble Space Telescope". The Astrophysical Journal Letters. 875 (2): L28. arXiv:1904.08821. Bibcode:2019ApJ...875L..28C. doi:10.3847/2041-8213/ab14e5. ISSN 2041-8205.

- Lykhin, Aleksandr O.; Ahmadvand, Seyedsaeid; Varganov, Sergey A. (2018-12-18). "Electronic Transitions Responsible for C60+ Diffuse Interstellar Bands". The Journal of Physical Chemistry Letters. 10 (1): 115–120. doi:10.1021/acs.jpclett.8b03534. ISSN 1948-7185. PMID 30560674.