Dhole

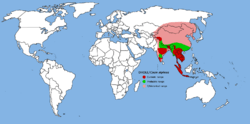

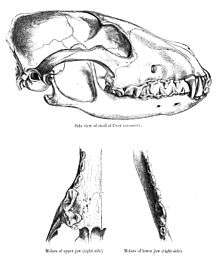

The dhole (/doʊl/; Cuon alpinus) is a canid native to Central, South, East Asia, and Southeast Asia. Other English names for the species include Asian wild dog, Asiatic wild dog,[2] Indian wild dog,[3] whistling dog, red dog,[4] and mountain wolf.[5] It is genetically close to species within the genus Canis,[6](Fig. 10) but distinct in several anatomical aspects: its skull is convex rather than concave in profile, it lacks a third lower molar[7] and the upper molars sport only a single cusp as opposed to between two and four.[8] During the Pleistocene, the dhole ranged throughout Asia, Europe, and North America but became restricted to its historical range 12,000–18,000 years ago.[9]

| Dhole | |

|---|---|

_cropped.jpg) | |

| An Ussuri dhole (Cuon alpinus alpinus) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Subfamily: | Caninae |

| Tribe: | Canini |

| Genus: | Cuon Hodgson, 1838 |

| Species: | C. alpinus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cuon alpinus (Pallas, 1811) | |

| |

| Dhole range | |

The dhole is a highly social animal, living in large clans without rigid dominance hierarchies[10] and containing multiple breeding females.[11] Such clans usually consist of 12 individuals, but groups of over 40 are known.[4] It is a diurnal pack hunter which preferentially targets medium- and large-sized ungulates.[12] In tropical forests, the dhole competes with tiger and leopard, targeting somewhat different prey species, but still with substantial dietary overlap.[13]

It is listed as Endangered by the IUCN as populations are decreasing and are estimated at fewer than 2,500 adults. Factors contributing to this decline include habitat loss, loss of prey, competition with other species, persecution due to livestock predation and disease transfer from domestic dogs.[1]

Etymology and naming

The etymology of "dhole" is unclear. The possible earliest written use of the word in English occurred in 1808 by soldier Thomas Williamson, who encountered the animal in Ramghur district. He stated that dhole was a common local name for the species.[14] In 1827, Charles Hamilton Smith claimed that it was derived from a language spoken in 'various parts of the East'.[15]

Two years later, Smith connected this word with Turkish: deli 'mad, crazy', and erroneously compared the Turkish word with Old Saxon: dol and Dutch: dol (cfr. also English: dull; German: toll),[16] which are in fact from the Proto-Germanic *dwalaz 'foolish, stupid'.[17] Richard Lydekker wrote nearly 80 years later that the word was not used by the natives living within the species' range.[3] The Merriam-Webster Dictionary theorises that it may have come from the Kannada: tōḷa ('wolf').[18]

Taxonomy and evolution

Canis alpinus was the binomial name proposed by Peter Simon Pallas in 1811, who described its range as encompassing the upper levels of Udskoi Ostrog in Amurland, towards the eastern side and in the region of the upper Lena River, around the Yenisei River and occasionally crossing into China.[19][20] This northern Russian range reported by Pallas during the 18th and 19th centuries is "considerably north" of where this species occurs today.[20]

Canis primaevus was a name proposed by Brian Houghton Hodgson in 1833 who thought that the dhole is a primitive Canis form and the progenitor of the domestic dog.[21] Hodgson later took note of the dhole's physical distinctiveness from the genus Canis and proposed the genus Cuon.[22]

The first study on the origins of the species was conducted by paleontologist Erich Thenius, who concluded that the dhole was a post-Pleistocene descendant of a golden jackal-like ancestor.[23] The earliest known member of the genus Cuon is the Chinese Cuon majori of the Villafranchian period. It resembled Canis in its physical form more than the modern species, which has greatly reduced molars, whose cusps have developed into sharply trenchant points. By the Middle Pleistocene, C. majori had lost the last lower molar altogether. C. alpinus itself arose during the late Middle Pleistocene, by which point the transformation of the lower molar into a single cusped, slicing tooth had been completed.

Late Middle Pleistocene dholes were virtually indistinguishable from their modern descendants, save for their greater size, which closely approached that of the gray wolf. The dhole became extinct in much of Europe during the late Würm period,[25] though it may have survived up until the early Holocene in the Iberian Peninsula.[26] and at Riparo Fredian in northern Italy[27] The vast Pleistocene range of this species also included numerous islands in Asia that this species no longer inhabits, such as Sri Lanka, Borneo and possibly Palawan in the Philippines.[28][29][30][31][32] The fossil record indicates that the species also occurred in North America, with remains being found in Beringia and Mexico.[33]

The dhole's distinctive morphology has been a source of much confusion in determining the species' systematic position among the Canidae. George Simpson placed the dhole in the subfamily Simocyoninae alongside the African wild dog and the bush dog, on account of all three species' similar dentition.[34] Subsequent authors, including Juliet Clutton-Brock, noted greater morphological similarities to canids of the genera Canis, Dusicyon, and Alopex than to either Speothos or Lycaon, with any resemblance to the latter two being due to convergent evolution.[7]

Some authors consider the extinct Canis subgenus named Xenocyon as ancestral to both the genus Lycaon and the genus Cuon.[35][36][37][38]:p149 Subsequent studies on the canid genome revealed that the dhole and African wild dog are closely related to members of the genus Canis.[6] This closeness to Canis may have been confirmed in a menagerie in Madras, where according to zoologist Reginald Pocock there is a record of a dhole interbred with a golden jackal.[39]

| Phylogenetic tree of the extant wolf-like canids | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phylogenetic relationships between the extant wolf-like clade of canids based on nuclear DNA sequence data taken from the cell nucleus,[6][40] except for the Himalayan wolf, based on mitochondrial DNA sequences.[40][41] Timing in millions of years.[40] |

Admixture with the African wild dog

In 2018, whole genome sequencing was used to compare all members (apart from the black-backed and side-striped jackals) of the genus Canis, along with the dhole and the African wild dog (Lycaon pictus). There was strong evidence of ancient genetic admixture between the dhole and the African wild dog. Today, their ranges are remote from each other; however, during the Pleistocene era the dhole could be found as far west as Europe. The study proposes that the dhole's distribution may have once included the Middle East, from where it may have admixed with the African wild dog in North Africa. However, there is no evidence of the dhole having existed in the Middle East nor North Africa.[42]

Subspecies

Historically, up to 10 subspecies of dholes have been recognised.[43] As of 2005, seven subspecies are recognised by MSW3.[44][45]

| Subspecies | Image | Trinomial authority | Description | Distribution | Synonyms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C. a. adjustus Burmese dhole[39] | Pocock, 1941[39] | Reddish coat, short hair on the paws and black whiskers.[46] | Northeastern India and south of the Ganges river, northern Myanmar.[46] | antiquus (Matthew & Granger, 1923), dukhunensis (Sykes, 1831) | |

| C. a. alpinus Ussuri red wolf[8]

Red wolf,[47] (Nominate subspecies) |

|

Pallas, 1811[47] | Thick tawny red coat greyish neck and ochre muzzle.[46] | East of eastern Sayan Mountains, East Russia, Northeastern Asia.[46] | |

| C. a. fumosus Asiatic dhole[48] | Pocock, 1936[48] | Luxuriant yellowish-red coat, dark back and grey neck.[46] | Western Szechuan, China and Mongolia. Southern Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia, and Java, Indonesia.[46] | infuscus (Pocock, 1936), javanicus (Desmarest, 1820) | |

| C. a. hesperius

Tien Shan dhole[8] |

|

Afanasjev and Zolotarev, 1935[49] | Long yellow tinted coat, white underside and pale whiskers.[46] Smaller than C. a. alpinus, with wider skull and lighter-coloured winter fur.[8] | Eastern Russia and China.[46] | jason (Pocock, 1936) |

| C. a. laniger Asiatic dhole[48] | Pocock, 1936[48] | Full, yellowish-grey coat, tail not black but same colour as

body.[46] |

Southern Tibet, Himalayan Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and Kashmir.[46] | grayiformis (Hodgson, 1863), primaevus (Hodgson, 1833) | |

| C. a. lepturus Asiatic dhole[48] | Heude, 1892[50] | Uniform red coat with thick underfur.[46] | South of the Yangtze River, China.[46] | clamitans (Heude, 1892), rutilans (Müller, 1839), sumatrensis (Hodgson, 1833) | |

| C. a. sumatrensis Sumatran wild dog[51] |  |

Hardwicke, 1821[51] | Red coat and dark whiskers.[46] | Sumatra, Indonesia.[46] | |

However, studies on the dhole's mtDNA and microsatellite genotype showed no clear subspecific distinctions. Nevertheless, two major phylogeographic groupings were discovered in dholes of the Asian mainland, which likely diverged during a glaciation event. One population extends from South, Central and North India (south of the Ganges) into Myanmar, and the other extends from India north of the Ganges into northeastern India, Myanmar, Thailand and the Malaysian Peninsula. The origin of dholes in Sumatra and Java is, as of 2005, unclear, as they show greater relatedness to dholes in India, Myanmar and China rather than with those in nearby Malaysia. In the absence of further data, the researchers involved in the study speculated that Javan and Sumatran dholes could have been introduced to the islands by humans.[52]

Characteristics

In appearance, the dhole has been variously described as combining the physical characteristics of the gray wolf and the red fox,[8] and as being "cat-like" on account of its long backbone and slender limbs.[23] It has a wide and massive skull with a well-developed sagittal crest,[8] and its masseter muscles are highly developed compared to other canid species, giving the face an almost hyena-like appearance.[53] The rostrum is shorter than that of domestic dogs and most other canids.[4] The species has six rather than seven lower molars.[54] The upper molars are weak, being one third to one half the size of those of wolves and have only one cusp as opposed to between two and four, as is usual in canids,[8] an adaptation thought to improve shearing ability, thus allowing it to compete more successfully with kleptoparasites.[12] Adult females can weigh from 10 to 17 kg (22 to 37 lb), while the slightly larger male may weigh from 15 to 21 kg (33 to 46 lb). The mean weight of adults from three small samples was 15.1 kg (33 lb).[12][55][56][57] Occasionally, dholes may be sympatric with the Indian wolf (Canis lupus pallipes), which is one of the smallest races of the gray wolf, but is still approximately 25% heavier on average.[58][59] It stands 17 to 22 in (430 to 560 mm) at the shoulder and measures 3 ft (0.91 m) in body length. Its ears are somewhat rounded, but less so than the African wild dog.

The general tone of the fur is reddish, with the brightest hues occurring in winter. In the winter coat, the back is clothed in a saturated rusty-red to reddish colour with brownish highlights along the top of the head, neck and shoulders. The throat, chest, flanks, and belly and the upper parts of the limbs are less brightly coloured, and are more yellowish in tone. The lower parts of the limbs are whitish, with dark brownish bands on the anterior sides of the forelimbs. The muzzle and forehead are greyish-reddish. The tail is very luxuriant and fluffy, and is mainly of a reddish-ocherous colour, with a dark brown tip. The summer coat is shorter, coarser, and darker.[8] The dorsal and lateral guard hairs in adults measure 20–30 mm in length. Dholes in the Moscow Zoo moult once a year from March to May.[4]

Dholes produce whistles resembling the calls of red foxes, sometimes rendered as coo-coo. How this sound is produced is unknown, though it is thought to help in coordinating the pack when travelling through thick brush. When attacking prey, they emit screaming KaKaKaKAA sounds.[60] Other sounds include whines (food soliciting), growls (warning), screams, chatterings (both of which are alarm calls) and yapping cries.[61] In contrast to wolves, dholes do not howl or bark.[8] Dholes have a complex body language. Friendly or submissive greetings are accompanied by horizontal lip retraction and the lowering of the tail, as well as licking. Playful dholes open their mouths with their lips retracted and their tails held in a vertical position whilst assuming a play bow. Aggressive or threatening dholes pucker their lips forward in a snarl and raise the hairs on their backs, as well as keep their tails horizontal or vertical. When afraid, they pull their lips back horizontally with their tails tucked and their ears flat against the skull.[62]

Distribution and habitat

.jpg)

The dhole still occurs in Tibet and possibly also in North Korea. It once inhabited the alpine steppes extending into Kashmir to the Ladakh area, but has not been recorded in Pakistan.[1] In Central Asia, the dhole primarily inhabits mountainous areas; in the western part of its range, it lives mostly in alpine meadows and high-montane steppes high above sea level, while in the east, it mainly ranges in montane taigas, and is sometimes sighted along coastlines. In India, Myanmar, Indochina, Indonesia and China, it prefers forested areas in alpine zones and occasionally also in plains regions.[8]

The dhole might still be present in the Tunkinsky National Park in extreme southern Siberia near Lake Baikal.[63] It possibly still lives in the Primorsky Krai province in far eastern Russia, where it was considered a rare and endangered species in 2004, with unconfirmed reports in the Pikthsa-Tigrovy Dom protected forest area; no sighting was reported in other areas since the late 1970s.[64] Currently, no other recent reports are confirmed of dhole being present in Russia.[65]

One pack was sighted in the Qilian Mountains in 2006.[66] In 2011 to 2013, local government officials and herders reported the presence of several dhole packs at elevations of 2,000 to 3,500 m (6,600 to 11,500 ft) near Taxkorgan Nature Reserve in the Xinjiang Autonomous Region. Several packs and a female adult with pups were also recorded by camera traps at elevations of around 2,500 to 4,000 m (8,200 to 13,100 ft) in Yanchiwan National Nature Reserve in the northern Gansu Province in 2013–2014.[67] Dholes have been also reported in the Altyn-Tagh Mountains.[68]

In China's Yunnan Province, dholes were recorded in Baima Xueshan Nature Reserve in 2010–2011.[69] Dhole samples from wild animals were recently obtained in the Jiangxi Province in 2013.[70]. Confirmed records by camera-trapping since 2008 have occurred in southern and western Gansu province, southern Shaanxi province, southern Qinghai province, southern and western Yunnan province, western Sichuan province, the southern Xinjiang Autonomous Region and in the Southeastern Tibet Autonomoous Region.[71]

The dhole occurs in most of India south of the Ganges, particularly in the Central Indian Highlands and the Western and Eastern Ghats. It is also present in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Meghalaya, and West Bengal and in the Indo-Gangetic Plain's Terai region. Dhole populations in the Himalayas and northwest India are fragmented.[1]

In 2011, dhole packs were recorded by camera traps in the Chitwan National Park.[72] Its presence was confirmed in the Kanchenjunga Conservation Area in 2011 by camera traps.[73] In February 2020, dholes were sighted in the Vansda National Park, with camera traps confirming the presence of two individuals in May of the same year. This was the first confirmed sighting of dholes in Gujarat since 1970.[74]

In Bhutan, the dhole is present in Jigme Dorji National Park.[75][76]

In Bangladesh, it inhabits forest reserves in the Sylhet area, as well the Chittagong Hill Tracts in the southeast. Recent camera trap photos in the Chittagong in 2016 showed the continued presence of the dhole [77]. These regions probably do not harbour a viable population, as mostly small groups or solitary individuals were sighted.[1]

In Myanmar, the dhole is present in several protected areas.[1] In 2015, dholes and tigers were recorded by camera-traps for the first time in the hill forests of Karen State.[78]

Its range is highly fragmented in the Malaysian Peninsula, Sumatra, Java, Vietnam and Thailand.[1] In 2014, camera trap videos in the montane tropical forests at 2,000 m (6,600 ft) in the Kerinci Seblat National Park in Sumatra revealed its continued presence.[79] A camera trapping survey in the Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary in Thailand from January 2008 to February 2010 documented one healthy dhole pack.[80] In northern Laos, dholes were studied in Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area.[81] Camera trap surveys from 2012-2017 recorded dholes in the same Nam Et-Phou Louey National Protected Area.[82]

In Vietnam, dholes were sighted only in Pu Mat National Park in 1999, in Yok Don National Park in 2003 and 2004; and in Ninh Thuan Province in 2014.[83]

A disjunct dhole population was reported in the area of Trabzon and Rize in northeastern Turkey near the border with Georgia in the 1990s.[84] This report was not considered to be reliable.[1] One single individual was claimed to have been shot in 2013 in the nearby Kabardino-Balkaria Republic in the central Caucasus); its remains were analysed in May 2015 by a biologist from the Kabardino-Balkarian State University, who concluded that the skull was indeed of a dhole.[85] In August 2015, researchers from the National Museum of Natural History and the Karadeniz Technical University started an expedition to track and document this possible Turkish population of dhole.[86] In October 2015, they concluded that no real evidence exists of a living dhole population in Turkey or in the Kabardino-Balkaria Republic, pending DNA analysis of samples from the original 1994 skins.[87]

Ecology and behaviour

Social and territorial behaviour

Dholes are more social than gray wolves,[8] and have less of a dominance hierarchy, as seasonal scarcity of food is not a serious concern for them. In this manner, they closely resemble African wild dogs in social structure.[10] They live in clans rather than packs, as the latter term refers to a group of animals that always hunt together. In contrast, dhole clans frequently break into small packs of 3 to 5 animals, particularly during the spring season, as this is the optimal number for catching fawns.[88] Dominant dholes are hard to identify, as they do not engage in dominance displays as wolves do, though other clan members will show submissive behaviour toward them.[11] Intragroup fighting is rarely observed.[89]

Dholes are far less territorial than wolves, with pups from one clan often joining another without trouble once they mature sexually.[90] Clans typically number 5 to 12 individuals in India, though clans of 40 have been reported. In Thailand, clans rarely exceed three individuals.[4] Unlike other canids, there is no evidence of dholes using urine to mark their territories or travel routes. When urinating, dholes, especially males, may raise one hind leg or both to result in a handstand. Handstand urination is also seen in bush dogs (Speothos venaticus).[91] They may defecate in conspicuous places, though a territorial function is unlikely, as faeces are mostly deposited within the clan's territory rather than the periphery. Faeces are often deposited in what appear to be communal latrines. They do not scrape the earth with their feet, as other canids do, to mark their territories.[62]

Denning

Four kinds of den have been described; simple earth dens with one entrance (usually remodeled striped hyena or porcupine dens); complex cavernous earth dens with more than one entrance; simple cavernous dens excavated under or between rocks; and complex cavernous dens with several other dens in the vicinity, some of which are interconnected. Dens are typically located under dense scrub or on the banks of dry rivers or creeks. The entrance to a dhole den can be almost vertical, with a sharp turn three to four feet down. The tunnel opens into an antechamber, from which extends more than one passage. Some dens may have up to six entrances leading up to 100 feet (30 m) of interconnecting tunnels. These "cities" may be developed over many generations of dholes, and are shared by the clan females when raising young together.[92] Like African wild dogs and dingoes, dholes will avoid killing prey close to their dens.[93]

Reproduction and development

In India, the mating season occurs between mid-October and January, while captive dholes in the Moscow Zoo breed mostly in February.[4] Unlike wolf packs, dhole clans may contain more than one breeding female.[11] More than one female dhole may den and rear their litters together in the same den.[89] During mating, the female assumes a crouched, cat-like position. There is no copulatory tie characteristic of other canids when the male dismounts. Instead, the pair lie on their sides facing each other in a semicircular formation.[94] The gestation period lasts 60–63 days, with litter sizes averaging four to six pups.[4] Their growth rate is much faster than that of wolves, being similar in rate to that of coyotes.

The hormone metabolites of five males and three females kept in Thai zoos was studied. The breeding males showed an increased level of testosterone from October to January. The oestrogen level of captive females increases for about 2 weeks in January, followed by an increase of progesterone. They displayed sexual behaviours during the oestrogen peak of the females.[95]

Pups are suckled at least 58 days. During this time, the pack feeds the mother at the den site. Dholes do not use rendezvous sites to meet their pups as wolves do, though one or more adults will stay with the pups at the den while the rest of the pack hunts. Once weaning begins, the adults of the clan will regurgitate food for the pups until they are old enough to join in hunting. They remain at the den site for 70–80 days. By the age of six months, pups accompany the adults on hunts and will assist in killing large prey such as sambar by the age of eight months.[93] Maximum longevity in captivity is 15–16 years.[89]

Hunting behaviour

Before embarking on a hunt, clans go through elaborate prehunt social rituals involving nuzzling, body rubbing and homo- and heterosexual mounting.[96] Dholes are primarily diurnal hunters, hunting in the early hours of the morning. They rarely hunt nocturnally, except on moonlit nights, indicating they greatly rely on sight when hunting.[97] Although not as fast as jackals and foxes, they can chase their prey for many hours.[8] During a pursuit, one or more dholes may take over chasing their prey, while the rest of the pack keeps up at a steadier pace behind, taking over once the other group tires. Most chases are short, lasting only 500 m.[98] When chasing fleet-footed prey, they run at a pace of 30 mph (48 km/h).[8] Dholes frequently drive their prey into water bodies, where the targeted animal's movements are hindered.[99]

Once large prey is caught, one dhole will grab the prey's nose, while the rest of the pack pulls the animal down by the flanks and hindquarters. They do not use a killing bite to the throat.[100] They occasionally blind their prey by attacking the eyes.[101] Serows are among the only ungulate species capable of effectively defending themselves against dhole attacks, due to their thick, protective coats and short, sharp horns capable of easily impaling dholes.[3] They will tear open their prey's flanks and disembowel it, eating the heart, liver, lungs and some sections of the intestines. The stomach and rumen are usually left untouched.[102] Prey weighing less than 50 kg is usually killed within two minutes, while large stags may take 15 minutes to die. Once prey is secured, dholes will tear off pieces of the carcass and eat in seclusion.[103] Unlike wolf packs, in which the breeding pair monopolises food, dholes give priority to the pups when feeding at a kill, allowing them to eat first.[11] They are generally tolerant of scavengers at their kills.[104] Both mother and young are provided with regurgitated food by other pack members.[89]

Feeding ecology

Prey animals in India include chital, sambar deer, muntjac, mouse deer, barasingha, wild boar, gaur, water buffaloes, banteng, cattle, nilgai, goats, Indian hares, Himalayan field rats and langurs.[4][39][105] There is one record of a pack bringing down an Indian elephant calf in Assam, despite desperate defense of the mother, resulting in numerous losses to the pack.[5] In Kashmir, they prey on markhor,[39] and thamin in Myanmar,[4] Malayan tapir, Sumatran serow in Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula and Javan rusa in Java.[12] In the Tian Shan and Tarbagatai Mountains, dholes prey on Siberian ibexes, arkhar, roe deer, maral and wild boar. In the Altai and Sayan Mountains, they prey on musk deer and reindeer. In eastern Siberia, they prey on roe deer, Manchurian wapiti, wild pig, musk deer and reindeer, while in Primorye they feed on sika deer and goral. In Mongolia, they prey on argali and rarely Siberian ibex.[8]

Like African wild dogs, but unlike wolves, dholes are not known to attack people.[8][39] Dholes eat fruit and vegetable matter more readily than other canids. In captivity, they eat various kinds of grasses, herbs and leaves, seemingly for pleasure rather than just when ill.[106] In summertime in the Tian Shan Mountains, dholes eat large quantities of mountain rhubarb.[8] Although opportunistic, dholes have a seeming aversion to hunting cattle and their calves.[107] Livestock predation by dholes has been a problem in Bhutan since the late 1990s, as domestic animals are often left outside to graze in the forest, sometimes for weeks at a time. Livestock stall-fed at night and grazed near homes are never attacked. Oxen are killed more often than cows, probably because they are given less protection.[108]

Enemies and competitors

In some areas, dholes are sympatric to tigers and leopards. Competition between these species is mostly avoided through differences in prey selection, although there is still substantial dietary overlap. Along with leopards, dholes typically target animals in the 30–175 kg range (mean weights of 35.3 kg for dhole and 23.4 kg for leopard), while tigers selected for prey animals heavier than 176 kg (but their mean prey weight was 65.5 kg). Also, other characteristics of the prey, such as sex, arboreality and aggressiveness, may play a role in prey selection. For example, dholes preferentially select male chital, whereas leopards kill both sexes more evenly (and tigers prefer larger prey altogether), dholes and tigers kill langurs rarely compared to leopards due to the leopards' greater arboreality, while leopards kill wild boar infrequently due to the inability of this relatively light predator to tackle aggressive prey of comparable weight.[13]

On some occasions, dholes may attack tigers. When confronted by dholes, tigers will seek refuge in trees or stand with their backs to a tree or bush, where they may be mobbed for lengthy periods before finally attempting escape. Escaping tigers are usually killed, while tigers which stand their ground have a greater chance of survival.[39] Tigers are dangerous opponents for dholes, as they have sufficient strength to kill a dhole with a single paw strike.[5] Dhole packs may steal leopard kills, while leopards may kill dholes if they encounter them singly or in pairs.[39] Since leopards are smaller than tigers and are more likely to hunt dholes, dhole packs tend to react more aggressively toward them than they do towards tigers.[109]

There are numerous records of leopards being treed by dholes.[89] Dholes sometimes drive tigers, leopards, snow leopards and bears (see below) from their kills.[89] Dholes were once thought to be a major factor in reducing Asiatic cheetah populations, though this is doubtful, as cheetahs live in open areas as opposed to forested areas favoured by dholes.[110]

Dhole packs occasionally attack Asiatic black bears, snow leopards, and sloth bears. When attacking bears, dholes will attempt to prevent them from seeking refuge in caves and lacerate their hindquarters.[39]

Although usually antagonistic toward wolves,[8] they may hunt and feed alongside one another.[111] There is at least one record of a lone wolf associating with a pair of dholes in Debrigarh Wildlife Sanctuary.[112] They infrequently associate in mixed groups with Eurasian golden jackals. Domestic dogs may kill dholes, though they will feed alongside them on occasion.[113]

Diseases and parasites

Dholes are vulnerable to a number of different diseases, particularly in areas where they are sympatric with other canid species. Infectious pathogens such as Toxocara canis are present in their faeces. They may suffer from rabies, canine distemper, mange, trypanosomiasis, canine parvovirus and endoparasites such as cestodes and roundworms.[12]

Threats

The dhole only rarely takes domestic livestock. Certain people, such as the Kurumbas and some Mon Khmer-speaking tribes will appropriate dhole kills; some Indian villagers welcome the dhole because of this appropriation of dhole kills.[89] Dholes were persecuted throughout India for bounties until they were given protection by the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972. Methods used for dhole hunting included poisoning, snaring, shooting and clubbing at den sites. Native Indian people killed dholes primarily to protect livestock, while British sporthunters during the British Raj did so under the conviction that dholes were responsible for drops in game populations. Persecution of dholes still occurs with varying degrees of intensity according to the region.[12] Bounties paid for dholes used to be 25 rupees, though this was reduced to 20 in 1926 after the number of presented dhole carcasses became too numerous to maintain the established reward.[114] In Indochina, dholes suffer heavily from nonselective hunting techniques such as snaring.[12]

The fur trade does not pose a significant threat to dholes.[12] The people of India do not eat dhole flesh and their fur is not considered overly valuable.[106] Due to their rarity, dholes were never harvested for their skins in large numbers in the Soviet Union and were sometimes accepted as dog or wolf pelts (being labeled as "half wolf" for the latter). The winter fur was prized by the Chinese, who bought dhole pelts in Ussuriysk during the late 1860s for a few silver rubles. In the early 20th century, dhole pelts reached eight rubles in Manchuria. In Semirechye, fur coats made from dhole skin were considered the warmest, but were very costly.[8]

Conservation

In India, the dhole is protected under Schedule 2 of the Wildlife Protection Act, 1972. The creation of reserves under Project Tiger provided some protection for dhole populations sympatric with tigers. In 2014, the Indian government sanctioned its first dhole conservation breeding centre at the Indira Gandhi Zoological Park (IGZP) in Visakhapatnam.[115] The dhole has been protected in Russia since 1974, though it is vulnerable to poison left out for wolves. In China, the animal is listed as a category II protected species under the Chinese wildlife protection act of 1988. In Cambodia, the dhole is protected from all hunting, while conservation laws in Vietnam limit extraction and utilisation.[1]

In 2016, the Korean company Sooam Biotech was reported to be attempting to clone the dhole using dogs as surrogate mothers to help conserve the species.[116]

In culture and literature

Three dhole-like animals are featured on the coping stone of the Bharhut stupa dating from 100 BC. They are shown waiting by a tree, with a woman or spirit trapped up it, a scene reminiscent of dholes treeing tigers.[117] The animal's fearsome reputation in India is reflected by the number of pejorative names it possesses in Hindi, which variously translate as "red devil", "devil dog", "jungle devil", or "hound of Kali".[5] According to zoologist and explorer Leopold von Schrenck, he had trouble obtaining dhole specimens during his exploration of Amurland, as the local Gilyaks greatly feared the species. This fear and superstition was not, however, shared by neighbouring Tungusic peoples.

Von Schrenk speculated that this differing attitude towards dholes was due to the Tungusic people's more nomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle.[24] Dhole-like animals are described in numerous old European texts, including the Ostrogoth sagas, where they are portrayed as hellhounds.[16] The demon dogs accompanying Hellequin in Mediaeval French Passion Plays, as well as the ones inhabiting the legendary forest of Brocéliande, have been attributed to dholes.[16] According to Charles Hamilton Smith, the dangerous wild canids mentioned by Scaliger as having lived in the forests of Montefalcone could have been based on dholes, as they were described as unlike wolves in habits, voice and appearance. The Montefalcone family's coat of arms had a pair of red dogs as supporters.[16]

Dholes appear in Rudyard Kipling's Red Dog, where they are portrayed as aggressive and bloodthirsty animals which descend from the Deccan Plateau into the Seeonee Hills inhabited by Mowgli and his adopted wolf pack to cause carnage among the jungle's denizens. They are described as living in packs numbering hundreds of individuals, and that even Shere Khan and Hathi make way for them when they descend into the jungle. The dholes are despised by the wolves because of their destructiveness, their habit of not living in dens and the hair between their toes. With Mowgli and Kaa's help, the Seeonee wolf pack manages to wipe out the dholes by leading them through bee hives and torrential waters before finishing off the rest in battle.

Japanese author Uchida Roan wrote 犬物語 (Inu monogatari; A dog's tale) in 1901 as a nationalistic critique of the declining popularity of indigenous dog breeds, which he asserted were descended from the dhole.[118] A fictional version of the dhole, imbued with supernatural abilities, appears in the season 6 episode of TV series The X-Files, titled "Alpha".

Dholes also appear as enemies in the video game Far Cry 4, alongside other predators such as the Bengal tiger, honey badger, snow leopard, clouded leopard, Tibetan wolf and Asian black bear. They can be found hunting the player and other NPCs across the map, but are easily killed, being one of the weakest enemies in the game. They once again appear in the video game Far Cry Primal, where they play similar roles as their counterparts in the previous game, but can now also be tamed and used in combat by Takkar, the main protagonist of the game.

Tameability

Brian Houghton Hodgson kept captured dholes in captivity, and found, with the exception of one animal, they remained shy and vicious even after 10 months.[106] According to Richard Lydekker, adult dholes are nearly impossible to tame, though pups are docile and can even be allowed to play with domestic dog pups until they reach early adulthood.[3] A dhole may have been presented as a gift to Ibbi-Sin as tribute.[119]

See also

References

- Kamler, J. F.; Songsasen, N.; Jenks, K.; Srivathsa, A.; Sheng, L. & Kunkel, K. (2015). "Cuon alpinus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T5953A72477893.

- Fox 1984

- Lydekker, R. (1907). The game animals of India, Burma, Malaya, and Tibet. London, UK: R. Ward Limited.

- Cohen J. A. (1978). "Cuon alpinus" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 100 (100): 1–3. doi:10.2307/3503800. JSTOR 3503800. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Perry, R. (1964). The World of the Tiger. London: Cassell.

- Lindblad-Toh, K.; Wade, C.M.; Mikkelsen, T.S.; Karlsson, E.K.; Jaffe, D.B.; Kamal, M.; Clamp, M.; Chang, J.L.; Kulbokas, E.J.; Zody, M.C.; Mauceli, E.; Xie, X.; Breen, M.; Wayne, R.K.; Ostrander, E.A.; Ponting, C.P.; Galibert, F.; Smith, D.R.; Dejong, P.J.; Kirkness, E.; Alvarez, P.; Biagi, T.; Brockman, W.; Butler, J.; Chin, C.W.; Cook, A.; Cuff, J.; Daly, M.J.; Decaprio, D.; et al. (2005). "Genome sequence, comparative analysis, and haplotype structure of the domestic dog". Nature. 438 (7069): 803–819. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..803L. doi:10.1038/nature04338. PMID 16341006.

- Clutton-Brock, J.; Corbet, G. G. & Hills, M. (1976). "A review of the family Canidae, with a classification by numerical methods". Bulletin of the British Museum of Natural History. 29: 179–180. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P., eds. (1998). "Genus Cuon Hodgson, 1838". Mammals of the Soviet Union. II. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution and National science Foundation. Part 1A: Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea Cows, Wolves, and Bears) pp. 566–586. ISBN 1-886106-81-9.

- Zhang, H.; Chen, L. (2010). "The complete mitochondrial genome of dhole Cuon alpinus: Phylogenetic analysis and dating evolutionary divergence within canidae". Molecular Biology Reports. 38 (3): 1651–1660. doi:10.1007/s11033-010-0276-y. PMID 20859694.

- Fox 1984, p. 85

- Fox 1984, pp. 86–7

- Durbin, L. S.; Venkataraman, A.; Hedges, S.; Duckworth, W. (2004). "Dhole Cuon alpinus (Pallas 1811)" (PDF). In Sillero-Zubiri, C.; Hoffmann, M.; Macdonald, D. W. (eds.). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals and Dogs. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. Gland, Switzerland; Cambridge, UK: IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. pp. x, 210–219.

- Karanth, K. U.; Sunquist, M. E. (1995). "Prey selection by tiger, leopard and dhole in tropical forests". Journal of Animal Ecology. 64 (4): 439–450. doi:10.2307/5647. JSTOR 5647.

- Williamson, T. (1808). Oriental field sports: being a complete, detailed, and accurate description of the wild sports of the East. II. London: Orme.

- Smith, C. H. (1827). The class Mammalia. London: Geo. B. Whittaker.

- Smith, C. H.; Jardine, W. (1839). The natural history of dogs: Canidae or genus canis of authors; including also the genera hyaena and proteles. I. Edinburgh, UK: W.H. Lizars.

- Orel, V. (2003), A Handbook of Germanic Etymology, Leiden, DE; Boston, MA: Brill, p. 81, ISBN 978-90-04-12875-0

- dhole. Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

- Pallas, P. S. (1811). "Canis alpinus". Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica: Sistens omnium animalium in extenso Imperio Rossico, et adjacentibus maribus observatorum recensionem, domicilia, mores et descriptiones, anatomen atque icones plurimorum (in Latin). Petropoli: In officina Caes. Acadamiae Scientiarum Impress. pp. 34–35.

- Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P., eds. (1998). "Red Wolf Cuon alpinus Pallas, 1811". Mammals of the Soviet Union. II. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution and National science Foundation. Part 1A: Sirenia and Carnivora (Sea Cows, Wolves, and Bears) pp. 571–586.

- Hodgson, B. H. (1833). "Description and Characters of the Wild Dog of the Himalaya (Canis primævus)". Asiatic Researches. XVIII (2): 221–237, 235.

- Hodgson, B. H. (1842). "European notices of Indian canines, with further illustrations of the new genus Cuon vel Chrysæus". Calcutta Journal of Natural History. II: 205–209.

- Thenius, E. (1955). "Zur Abstammung der Rotwölfe (Gattung Cuon Hodgson)" [On the origins of the dholes (Genus Cuon Hodgson)] (PDF). Österreichische Zoologische Zeitschrift (in German). 5: 377–388.

- (in German) Schrenk, L. v. (1859), Reisen und forschungen im Amur-lande in den jahren 1854–1856, St. Petersburg : K. Akademie der Wissenschaften, pp. 48–50

- Kurtén, Björn (1968). Pleistocene mammals of Europe. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. pp. 111–114. ISBN 9781412845144.

- Ripoll, M.P.R.; Morales Pérez, J.V.; Sanchis Serra, A.; Aura Tortosa, J.E.; Montañana, I.S N. (2010). "Presence of the genus Cuon in upper Pleistocene and initial Holocene sites of the Iberian Peninsula: New remains identified in archaeological contexts of the Mediterranean region". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (3): 437–450. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2009.10.008.

- Petrucci, Mauro; Romiti, Serena; Sardella, Raffaele (2012). "The Middle-Late Pleistocene Cuon Hodgson, 1838 (Carnivora, Canidae) from Italy" (PDF). Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 51 (2): 146.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the World. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 9780801880322.

Cuon.

- Cranbrook, E. (1988). "The contribution of archaeology to the zoogeography of Borneo : with the first record of a wild canid of Early Holocene Age ; a contribution in celebration of the distinguished scholarship of Robert F. Inger on the occasion of his sixty-fifth birthday". Fieldiana Zoology. 42: 6–24.

- Ochoa, J.; Paz, V.; Lewis, H.; Carlos, J.; Robles, E.; Amano, N.; Ferreras, M. R.; Myra, L.; Vallejo, B. Jr. 5; G. Velarde; Villaluz, S. A.; Ronquillo, W.; Solheim, W. II (2004). "The archaeology and palaeobiological record of Pasimbahan-Magsanib Site, northern Palawan, Philippines". Philipine Science Letters. 7 (1): 22–36.

- Dennell, R.; Parr, M. (2014). Southern Asia, Australia, and the Search for Human Origins. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9781107729131.

- Tarling, N. (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia, Volume One, From Early Times to ca. 1800. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-5213-5505-6.

- Kurtén, B. (1980). Pleistocene mammals of North America. Columbia University Press. p. 172. ISBN 0231516967.

- Simpson, G.G. (1945). "The principles of classification and a classification of mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 85: 1–350. hdl:2246/1104.

- Moulle, P.E.; Echassoux, A.; Lacombat, F. (2006). "Taxonomie du grand canidé de la grotte du Vallonnet (Roquebrune-Cap-Martin, Alpes-Maritimes, France)". L'Anthropologie. 110 (5): 832–836. doi:10.1016/j.anthro.2006.10.001. Retrieved 28 April 2008. (in French)

- Baryshnikov Gennady F (2012). "Pleistocene Canidae (Mammalia, Carnivora) from the Paleolithic Kudaro caves in the Caucasus". Russian Journal of Theriology. 11 (2): 77–120. doi:10.15298/rusjtheriol.11.2.01.

- Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide F.; Rook, Lorenzo; Sardella, Raffaele (2013). "Re-Defining Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia): A New Look into the Evolutionary History of Early Pleistocene Dogs Resulting from the Outstanding Fossil Record from Pantalla (Italy)". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 21: 95–110. doi:10.1007/s10914-013-9227-4.

- Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

- Pocock, R.I. (1941). Fauna of British India: Mammals. 2. Taylor & Francis. pp. 146–163.

- Koepfli, K.-P.; Pollinger, J.; Godinho, R.; Robinson, J.; Lea, A.; Hendricks, S.; Schweizer, R. M.; Thalmann, O.; Silva, P.; Fan, Z.; Yurchenko, A. A.; Dobrynin, P.; Makunin, A.; Cahill, J. A.; Shapiro, B.; Álvares, F.; Brito, J. C.; Geffen, E.; Leonard, J. A.; Helgen, K. M.; Johnson, W. E.; O'Brien, S. J.; Van Valkenburgh, B.; Wayne, R. K. (17 August 2015). "Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Golden Jackals Are Distinct Species". Current Biology. 25 (16): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- Werhahn, Geraldine; Senn, Helen; Kaden, Jennifer; Joshi, Jyoti; Bhattarai, Susmita; Kusi, Naresh; Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; MacDonald, David W. (2017). "Phylogenetic evidence for the ancient Himalayan wolf: Towards a clarification of its taxonomic status based on genetic sampling from western Nepal". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (6): 170186. Bibcode:2017RSOS....470186W. doi:10.1098/rsos.170186. PMC 5493914. PMID 28680672.

- Gopalakrishnan, Shyam; Sinding, Mikkel-Holger S.; Ramos-Madrigal, Jazmín; Niemann, Jonas; Samaniego Castruita, Jose A.; Vieira, Filipe G.; Carøe, Christian; Montero, Marc de Manuel; Kuderna, Lukas; Serres, Aitor; González-Basallote, Víctor Manuel; Liu, Yan-Hu; Wang, Guo-Dong; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Mirarab, Siavash; Fernandes, Carlos; Gaubert, Philippe; Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Budd, Jane; Rueness, Eli Knispel; Heide-Jørgensen, Mads Peter; Petersen, Bent; Sicheritz-Ponten, Thomas; Bachmann, Lutz; Wiig, Øystein; Hansen, Anders J.; Gilbert, M. Thomas P. (2018). "Interspecific Gene Flow Shaped the Evolution of the Genus Canis". Current Biology. 28 (21): 3441–3449.e5. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2018.08.041. PMC 6224481. PMID 30344120.

- Ellerman, J.R. & Morrison-Scott, T.C.S. (1966). Checklist of Palaearctic and Indian mammals, British Museum (Natural History), London, UK.

- Wozencraft, C. W. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D. E.; Reader, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference. 1 (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 578. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0.

- Orrell T (2020). Nicolson D, Roskov Y, Abucay L, Orrell T, Nicolson D, Bailly N, Kirk PM, Bourgoin T, DeWalt RE, Decock W, De Wever A, van Nieukerken E, Zarucchi J, Penev L (eds.). "Cuon alpinus (Pallas, 1811) (accepted name)". Catalogue of Life: 2019 Annual Checklist. Catalogue of Life. Retrieved 5 February 2020. Latest taxonomic scrutiny:Wozencraft W.C., 20 November 2015

- Durbin, D.L.; Venkataraman, A.; Hedges, S.; Duckworth, W. (2004). "8.1–Dhole" (PDF). In Sillero-Zubiri, Claudio; Hoffmann, Michael; Macdonald, David Whyte (eds.). Canids: Foxes, Wolves, Jackals, and Dogs:Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN-The World Conservation Union. p. 211. ISBN 978-2831707860. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Pallas, P. S. (1811). "Canis alpinus". Zoographia Rosso-Asiatica: Sistens omnium animalium in extenso Imperio Rossico, et adjacentibus maribus observatorum recensionem, domicilia, mores et descriptiones, anatomen atque icones plurimorum (in Latin). Petropoli: In officina Caes. Acadamiae Scientiarum Impress. pp. 34–35.

"lupus rutilus" or red wolf.

- Pocock, R. I. (1936). "The Asiatic Wild Dog or Dhole (Cuon javanicus)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 106: 33–55. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1936.tb02278.x.

- Afanasjev, N. Zolotarev, “Contribution to the systematics and distribution of red wolf”, Bulletin de l'Académie des Sciences de l'URSS. Classe des sciences mathématiques et na, 1935, no. 3, 425–429

- Heude, Mém. Hist. Nat. Empire Chinois, II, pt2, p. 102 footnote 1892

- Descriptions of the Wild Dog of Sumatra, a new Species of Viverra, and a new Species of Pheasant. Hardwicke, Thomas. Transactions of the Linnean Society of London. Vol.3, pp235-8. 1821

- Iyengar, A.; Babu, V. N.; Hedges, S.; Venkataraman, A. B.; Maclean, N. & P. A. Morin (2005). "Phylogeography, genetic structure, and diversity in the dhole (Cuon alpinus)" (PDF). Molecular Ecology. 14 (8): 2281–2297. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02582.x. PMID 15969714.

- Fox 1984, pp. 61–2

- Fox 1984, pp. 41

- Kamler J. F.; Johnson A.; Vongkhamheng C.; Bousa A. (2012). "The diet, prey selection, and activity of dholes (Cuon alpinus) in northern Laos". Journal of Mammalogy. 93 (3): 627–633. doi:10.1644/11-mamm-a-241.1.

- Gittleman, J. L. (2013). Carnivore behavior, ecology, and evolution. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Atanasov, A. T. (2005). Alometric relationship between length of pregnancy and body mass of mammals. Bulg J Vet Med, 8(1), 20.

- Mukherjee S.; Zelcer M.; Kotler B. P. (2009). "Patch use in time and space for a meso-predator in a risky world". Oecologia. 159 (3): 661–668. Bibcode:2009Oecol.159..661M. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1243-3. PMID 19082629.

- Afik D.; Pinshow B. (1993). "Temperature regulation and water economy in desert wolves". Journal of Arid Environments. 24 (2): 197–209. Bibcode:1993JArEn..24..197A. doi:10.1006/jare.1993.1017.

- Fox 1984, p. 93

- Fox 1984, p. 95

- Fox 1984, p. 97

- Williams, M. & Troitskaya, N. (2007). "Then and Now: Updates from Russia's Imperiled Zapovedniks" (PDF). Russian Conservation News. 42: 14.

- Newell, J. (2004). The Russian Far East: A Reference Guide for Conservation and Development (Second ed.). McKinleyville: Daniel & Daniel.

- Makenov, M. (2018). "Extinct or extant? A review of dhole (Cuon alpinus Pallas, 1811) distribution in the former USSR and modern Russia". Mammal Research. 63 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1007/s13364-017-0339-8.

- Harris, R. B. (2006). "Attempted predation on blue sheep Pseudois nayaur by dholes Cuon alpinus". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 103: 95–97.

- Riordan, P. (2015). "New evidence of dhole Cuon alpinus populations in northwest China". Oryx. 49 (2): 203–204. doi:10.1017/s0030605315000046.

- Xue Yadong; Li Diqiang; Xiao Wenfa; Zhang Yuguang; Feng Bin; Jia Heng (2015). "Records of the dhole (Cuon alpinus) in an arid region of the Altun Mountains in western China". European Journal of Wildlife Research. 61 (6): 903–907. doi:10.1007/s10344-015-0947-z.

- Li, X.; Buzzard, P.; Chen, Y. & Jiang, X. (2013). "Patterns of livestock predation by carnivores: human-wildlife conflict in northwest Yunnan, China". Environ Manage. 52 (6): 1334–1340. doi:10.1007/s00267-013-0192-8.

- Best Practice Guideline Dhole (C. alpinus) (1.Edition): Canid and Hyaenid Taxon Advisory Group February18th, 2017. Amsterdam: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) Executive Office; 2017. p11. Accessed at: https://www.eaza.net/assets/Uploads/CCC/2017-Dhole-EAZA-Best-Practice-Guidelines-Approved.pdf

- Kao, J., N. Songsasen, K. Ferraz and K. Traylor-Holzer (Eds.) (2020). Range-wide Population and Habitat Viability Assessment for the Dhole, Cuon alpinus. IUCN SSC Conservation Planning Specialist Group, Apple Valley, MN, USA. p8. https://www.canids.org/resources/Dhole_PHVA_Report_2020.pdf

- Thapa, K.; Kelly, M. J.; Karki, J. B. & Subedi, N. (2013). "First camera trap record of pack hunting dholes in Chitwan National Park, Nepal" (PDF). Canid Biology & Conservation. 16 (2): 4–7.

- Khatiwada, A. P.; Awasthi, K. D.; Gautam, N. P.; Jnawali, S. R.; Subedi, N. & Aryal, A. (2011). "The Pack Hunter (Dhole): Received Little Scientific Attention". The Initiation. 4: 8–13. doi:10.3126/init.v4i0.5531.

- Parmar, Vijaysinh (23 May 2020). "Rare whistling dogs spotted in Gujarat after 50 years". Times of India. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Wangchuk, T. (2004). "Predator-prey dynamics: the role of predators in the control of problem species" (PDF). Journal of Bhutan Studies. 10: 68–89.

- Thinley, P.; Kamler, J. F.; Wang, S. W.; Lham, K.; Stenkewitz, U. (2011). "Seasonal diet of dholes (Cuon alpinus) in northwestern Bhutan". Mammalian Biology. 76 (4): 518–520. doi:10.1016/j.mambio.2011.02.003.

- https://www.theguardian.com/environment/radical-conservation/2016/mar/01/tiger-country-scientists-uncover-wild-surprises-in-tribal-bangladesh

- Saw Sha Bwe Moo; Froese, G.Z.L.; Gray, T. N. E. (2017). "First structured camera-trap surveys in Karen State, Myanmar, reveal high diversity of globally threatened mammals". Oryx. 52 (3): 1–7. doi:10.1017/S0030605316001113.

- "Sumatran secrets start to be revealed by high altitude camera trapping". Flora and Fauna International. Archived from the original on 1 May 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Jenks, K. E.; Songsasen, N. & P. Leimgruber (2012). "Camera trap records of dholes in Khao Ang Rue Nai Wildlife Sanctuary, Thailand" (PDF). Canid News: 1–5.

- Kamler J. F.; Johnson A.; Chanthavy, V.; Bousa, A. (2012). "The diet, prey selection, and activity of dholes (Cuon alpinus) in northern Laos". Journal of Mammalogy. 93 (3): 627–633. doi:10.1644/11-mamm-a-241.1.

- Rasphone, A; K�ery,M; Kamler,JF; and Macdonald, DA. 2019. "Documenting the demise of tiger and leopard, and the status of other carnivores and prey, in Lao PDR's most prized protected area: Nam Et - Phou Louey" Global Ecology and Conservation. 20:e00766 Accessed at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/335561711_Documenting_the_demise_of_tiger_and_leopard_and_the_status_of_other_carnivores_and_prey_in_Lao_PDR%27s_most_prized_protected_area_Nam_Et_-_Phou_Louey

- Hoffmann, M.; Abramov, A.; Duc, H.M.; Trai, L.T.; Long, B.; Nguyen, A.; Son, N.T.; Rawson, B.; Timmins, R.; Bang, T.V. & Willcox, D. (2019). "The status of wild canids (Canidae, Carnivora) in Vietnam". Journal of Threatened Taxa. 11 (8): 13951–13959. doi:10.11609/jott.4846.11.8.13951-13959.

- Serez, M. & Eroðlu, M. (1994). "A new threatened wolf species, Cuon alpinus hesperius Afanasiev and Zolatarev, 1935 in Turkey". Council of Europe Environmental Encounters Series. 17: 103–106.

- Khatukhov, A.M. (2015). "Красный волк (Cuon alpinus Pallas, 1811) на Центральном Кавказе" [The Dhole (Cuon alpinus Pallas 1811) in the Central Caucasus] (PDF). Современные проблемы науки и образования. 3: 574–581.

- "NMNHS expedition went on the trail of an unknown population of the rare dhole in Turkey". National Museum of Natural History, Sofia (NMNHS). 2015.

- Coel, C. (2015). "[UPDATE] Strongly endangered and undescribed subspecies of dhole discovered? Dhole NOT less endangered than previously thought, according to NMNHS (Bulgaria)". Consortium of European Taxonomic Facilities.

- Fox 1984, pp. 81–2

- Walker, E. P.; Nowak, R. M.; Warnick, F. (1983). Walker's Mammals of the World. 4th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Fox 1984, p. 92

- Keller, R. (1973). "Einige beobachtungen zum verhalten des Dekkan-Rothundes (Cuon alpinus dukhunensis Sykes) im Kanha National Park". Vierteljahresschrift. Naturf. Ges. Zürich (in German). 118: 129–135.

- Fox 1984, pp. 43–49

- Fox 1984, p. 80

- Fox 1984, p. 79

- Khonmee, J.; Rojanasthien, S.; Thitaram, C.; Sumretprasong, J.; Aunsusin, A.; Chaisongkram, C. & Songsasen, N. (2017). "Non-invasive endocrine monitoring indicates seasonal variations in gonadal hormone metabolites in dholes (Cuon alpinus)". Conservation Physiology. 5 (1): cox001. doi:10.1093/conphys/cox001. PMID 28852505.

- Fox 1984, pp. 100–1

- Fox 1984, p. 50

- Fox 1984, p. 73

- Fox 1984, p. 67

- Fox 1984, p. 61

- Grassman, L. I. Jr.; M. E. Tewes; N. J. Silvy; K. Kreetiyutanont (2005). "Spatial ecology and diet of the dhole Cuon alpinus (Canidae, Carnivora) in north central Thailand". Mammalia. 69 (1): 11–20. doi:10.1515/mamm.2005.002. Archived from the original on 23 November 2006.

- Fox 1984, p. 63

- Fox 1984, p. 70

- Fox 1984, p. 51

- Fox 1984, pp. 58–60

- Mivart, G. (1890), Dogs, Jackals, Wolves and Foxes: A Monograph of the Canidæ, London : R.H. Porter : Dulau, pp. 177–88

- Fox 1984, p. 71

- Johnsingh, A.J.T.; Yonten, D.; Wangchuck, S. (2007). "Livestock-Dhole Conflict in Western Bhutan". Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society. 104 (2): 201–202.

- Venkataraman, A. (1995). "Do dholes (Cuon alpinus) live in packs in response to competition with or predation by large cats?" (PDF). Current Science. 69 (11): 934–936.

- Finn, F. (1929). Sterndale's Mammalia of India. London: Thacker, Spink & Co.

- Shrestha, T. J. (1997). Mammals of Nepal: (with reference to those of India, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Pakistan). Kathmandu: Bimala Shrestha. ISBN 978-0-9524390-6-6.

- Nair M. V., Panda S. K. (2013). "Just Friends". Sanctuary Asia. XXXIII: 3.

- Humphrey, S. R.; Bain, J. R. (1990). Endangered Animals of Thailand. Gainesville: Sandhill Crane Press. ISBN 978-1-877743-07-8.

- Fox 1984, p. 109

- Zoo to have conservation breeding centre for ‘dhole’, The Hindu (18 August 2014)

- Zastrow, Mark (8 February 2016). "Inside the cloning factory that creates 500 new animals a day". New Scientist. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- van der Geer, A. A. E. (2008), Animals in stone: Indian mammals sculptured through time, BRILL, p. 188, ISBN 90-04-16819-2

- Skabelund, A. H. (2011). Empire of Dogs: Canines, Japan, and the Making of the Modern Imperial World. Cornell University Press, p. 85, ISBN 0801463246

- McIntosh, J. (2008). The ancient Indus Valley: new perspectives, p. 130, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 1-57607-907-4

Bibliography

- Fox, M. W. (1984). The Whistling Hunters: Field Studies of the Asiatic Wild Dog (Cuon Alpinus). Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-9524390-6-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Cuon alpinus |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cuon alpinus. |

| Look up dhole in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Dhole Home Page (Archive)

- ARKive – images and movies of the dhole

- Saving the dhole: The forgotten 'badass' Asian dog more endangered than tigers, The Guardian (25 June 2015)

- Photos of dhole in Bandipur