Allele

An allele (UK: /ˈæliːl/, /əˈliːl/; US: /əˈliːl/; modern formation from Greek ἄλλος állos, "other")[1][2][3] is a variant form of a given gene,[4] meaning it is one of two or more versions of a known mutation at the same place on a chromosome. It can also refer to different sequence variations for a several-hundred base-pair or more region of the genome that codes for a protein. Alleles can come in different extremes of size. At the lowest possible end one can be the single base choice of a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).[5] At the higher end, it can be the sequence variations for the regions of the genome that code for the same protein which can be up to several thousand base-pairs long.[6][7]

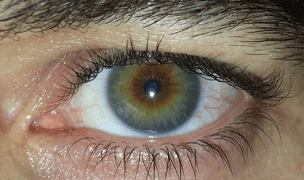

Sometimes, different alleles can result in different observable phenotypic traits, such as different pigmentation. A notable example of this trait of color variation is Gregor Mendel's discovery that the white and purple flower colors in pea plants were the result of "pure line" traits which could be used as a control for future experiments. However, most alleles result in little or no observable phenotypic variation.

Most multicellular organisms have two sets of chromosomes; that is, they are diploid. In this case, the chromosomes can be paired: each pair is a set of homologous chromosomes. If both alleles of a gene at the locus on the homologous chromosomes are the same, they and the organism are homozygous with respect to that gene. If the alleles are different, they and the organism are heterozygous with respect to that gene.

Etymology

The word "allele" is a short form of allelomorph ("other form", a word coined by British geneticists William Bateson and Edith Rebecca Saunders),[8][9] which was used in the early days of genetics to describe variant forms of a gene detected as different phenotypes. It derives from the Greek prefix ἀλληλο-, allelo-, meaning "mutual", "reciprocal", or "each other", which itself is related to the Greek adjective ἄλλος, allos (cognate with Latin alius), meaning "other".

Alleles that lead to dominant or recessive phenotypes

In many cases, genotypic interactions between the two alleles at a locus can be described as dominant or recessive, according to which of the two homozygous phenotypes the heterozygote most resembles. Where the heterozygote is indistinguishable from one of the homozygotes, the allele expressed is the one that leads to the "dominant" phenotype,[10] and the other allele is said to be "recessive". The degree and pattern of dominance varies among loci. This type of interaction was first formally described by Gregor Mendel. However, many traits defy this simple categorization and the phenotypes are modeled by co-dominance and polygenic inheritance.

The term "wild type" allele is sometimes used to describe an allele that is thought to contribute to the typical phenotypic character as seen in "wild" populations of organisms, such as fruit flies (Drosophila melanogaster). Such a "wild type" allele was historically regarded as leading to a dominant (overpowering - always expressed), common, and normal phenotype, in contrast to "mutant" alleles that lead to recessive, rare, and frequently deleterious phenotypes. It was formerly thought that most individuals were homozygous for the "wild type" allele at most gene loci, and that any alternative "mutant" allele was found in homozygous form in a small minority of "affected" individuals, often as genetic diseases, and more frequently in heterozygous form in "carriers" for the mutant allele. It is now appreciated that most or all gene loci are highly polymorphic, with multiple alleles, whose frequencies vary from population to population, and that a great deal of genetic variation is hidden in the form of alleles that do not produce obvious phenotypic differences.

Multiple alleles

A population or species of organisms typically includes multiple alleles at each locus among various individuals. Allelic variation at a locus is measurable as the number of alleles (polymorphism) present, or the proportion of heterozygotes in the population. A null allele is a gene variant that lacks the gene's normal function because it either is not expressed, or the expressed protein is inactive.

For example, at the gene locus for the ABO blood type carbohydrate antigens in humans,[11] classical genetics recognizes three alleles, IA, IB, and i, which determine compatibility of blood transfusions. Any individual has one of six possible genotypes (IAIA, IAi, IBIB, IBi, IAIB, and ii) which produce one of four possible phenotypes: "Type A" (produced by IAIA homozygous and IAi heterozygous genotypes), "Type B" (produced by IBIB homozygous and IBi heterozygous genotypes), "Type AB" produced by IAIB heterozygous genotype, and "Type O" produced by ii homozygous genotype. (It is now known that each of the A, B, and O alleles is actually a class of multiple alleles with different DNA sequences that produce proteins with identical properties: more than 70 alleles are known at the ABO locus.[12] Hence an individual with "Type A" blood may be an AO heterozygote, an AA homozygote, or an AA heterozygote with two different "A" alleles.)

Genotype frequencies

The frequency of alleles in a diploid population can be used to predict the frequencies of the corresponding genotypes (see Hardy–Weinberg principle). For a simple model, with two alleles;

where p is the frequency of one allele and q is the frequency of the alternative allele, which necessarily sum to unity. Then, p2 is the fraction of the population homozygous for the first allele, 2pq is the fraction of heterozygotes, and q2 is the fraction homozygous for the alternative allele. If the first allele is dominant to the second then the fraction of the population that will show the dominant phenotype is p2 + 2pq, and the fraction with the recessive phenotype is q2.

With three alleles:

- and

In the case of multiple alleles at a diploid locus, the number of possible genotypes (G) with a number of alleles (a) is given by the expression:

Allelic dominance in genetic disorders

A number of genetic disorders are caused when an individual inherits two recessive alleles for a single-gene trait. Recessive genetic disorders include albinism, cystic fibrosis, galactosemia, phenylketonuria (PKU), and Tay–Sachs disease. Other disorders are also due to recessive alleles, but because the gene locus is located on the X chromosome, so that males have only one copy (that is, they are hemizygous), they are more frequent in males than in females. Examples include red-green color blindness and fragile X syndrome.

Other disorders, such as Huntington's disease, occur when an individual inherits only one dominant allele.

Epialleles

While heritable traits are typically studied in terms of genetic alleles, epigenetic marks such as DNA methylation can be inherited at specific genomic regions in certain species, a process termed transgenerational epigenetic inheritance. The term epiallele is used to distinguish these heritable marks from traditional alleles, which are defined by nucleotide sequence.[13] A specific class of epiallele, the metastable epialleles, has been discovered in mice and in humans which is characterized by stochastic (probabilistic) establishment of epigenetic state that can be mitotically inherited.[14][15]

See also

References and notes

- "Allele | Meaning of Allele by Lexico". Lexico Dictionaries | English. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- "allele noun - Definition, pictures, pronunciation and usage notes". Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- "allele Meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 29 October 2017.

- Wood, E.J. (1995). "The encyclopedia of molecular biology". Biochemical Education. 23 (2): 1165. doi:10.1016/0307-4412(95)90659-2.

- Smigielski, Elizabeth M.; Sirotkin, Karl; Ward, Minghong; Sherry, Stephen T. (1 January 2000). "dbSNP: a database of single nucleotide polymorphisms". Nucleic Acids Research. 28 (1): 352–355. doi:10.1093/nar/28.1.352. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 102496. PMID 10592272.

- Elston, Robert; Satagopan, Jaya; Sun, Shuying (2012). "Genetic Terminology". Statistical Human Genetics. Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). 850. pp. 1–9. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-555-8_1. ISBN 978-1-61779-554-1. ISSN 1064-3745. PMC 4450815. PMID 22307690.

- "What effect do variants in coding regions have?". EMBL-EBI Train online. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- Craft, Jude (2013). "Genes and genetics: the language of scientific discovery". Genes and genetics. Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Bateson, W. and Saunders, E. R. (1902) "The facts of heredity in the light of Mendel’s discovery." Reports to the Evolution Committee of the Royal Society, I. pp. 125–160

- Hartl, Daniel L.; Elizabeth W. Jones (2005). Essential genetics: A genomics perspective (4th ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 600. ISBN 978-0-7637-3527-2.

- Victor A. McKusick; Cassandra L. Kniffin; Paul J. Converse; Ada Hamosh (10 November 2009). "ABO Glycosyltransferase; ABO". Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man. National Library of Medicine. Archived from the original on 24 September 2008. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- Yip SP (January 2002). "Sequence variation at the human ABO locus". Annals of Human Genetics. 66 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1017/S0003480001008995. PMID 12014997.

- Daxinger, Lucia; Whitelaw, Emma (31 January 2012). "Understanding transgenerational epigenetic inheritance via the gametes in mammals". Nature Reviews Genetics. 13 (3): 153–62. doi:10.1038/nrg3188. PMID 22290458.

- Rakyan, Vardhman K; Blewitt, Marnie E; Druker, Riki; Preis, Jost I; Whitelaw, Emma (July 2002). "Metastable epialleles in mammals". Trends in Genetics. 18 (7): 348–351. doi:10.1016/S0168-9525(02)02709-9. PMID 12127774.

- Waterland, RA; Dolinoy, DC; Lin, JR; Smith, CA; Shi, X; Tahiliani, KG (September 2006). "Maternal methyl supplements increase offspring DNA methylation at Axin Fused". Genesis. 44 (9): 401–6. doi:10.1002/dvg.20230. PMID 16868943.

External links

| Look up allele in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |