Rift Valley fever

Rift Valley fever (RVF) is a viral disease of humans and livestock that can cause mild to severe symptoms.[1] The mild symptoms may include: fever, muscle pains, and headaches which often last for up to a week.[1] The severe symptoms may include: loss of sight beginning three weeks after the infection, infections of the brain causing severe headaches and confusion, and bleeding together with liver problems which may occur within the first few days.[1] Those who have bleeding have a chance of death as high as 50%.[1]

| Rift Valley fever | |

|---|---|

| |

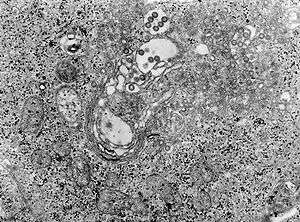

| TEM micrograph of tissue infected with Rift Valley fever virus | |

| Specialty | Infectious disease |

| Symptoms | Fever, muscle pains, headaches[1] |

| Complications | Loss of sight, confusion, bleeding, liver problems[1] |

| Duration | Up to a week[1] |

| Causes | Phlebovirus spread by an infected animal or mosquito[1] |

| Diagnostic method | Finding antibodies or the virus in the blood[1] |

| Prevention | Vaccinating animals against the disease, decreasing mosquito bites[1] |

| Treatment | Supportive care[1] |

| Frequency | Outbreaks in Africa and Arabia[1] |

The disease is caused by the RVF virus, which is of the Phlebovirus type.[1] It is spread by either touching infected animal blood, breathing in the air around an infected animal being butchered, drinking raw milk from an infected animal, or the bite of infected mosquitoes.[1] Animals such as cows, sheep, goats, and camels may be affected.[1] In these animals it is spread mostly by mosquitoes.[1] It does not appear that one person can infect another person.[1] The disease is diagnosed by finding antibodies against the virus or the virus itself in the blood.[1]

Prevention of the disease in humans is accomplished by vaccinating animals against the disease.[1] This must be done before an outbreak occurs because if it is done during an outbreak it may worsen the situation.[1] Stopping the movement of animals during an outbreak may also be useful, as may decreasing mosquito numbers and avoiding their bites.[1] There is a human vaccine; however, as of 2010 it is not widely available.[1] There is no specific treatment and medical efforts are supportive.[1]

Outbreaks of the disease have only occurred in Africa and Arabia.[1] Outbreaks usually occur during periods of increased rain which increase the number of mosquitoes.[1] The disease was first reported among livestock in Rift Valley of Kenya in the early 1900s,[2] and the virus was first isolated in 1931.[1]

Signs and symptoms

In humans, the virus can cause several syndromes. Usually, sufferers have either no symptoms or only a mild illness with fever, headache, muscle pains, and liver abnormalities. In a small percentage of cases (< 2%), the illness can progress to hemorrhagic fever syndrome, meningoencephalitis (inflammation of the brain and tissues lining the brain), or affect the eye. Patients who become ill usually experience fever, generalised weakness, back pain, dizziness, and weight loss at the onset of the illness. Typically, people recover within two to seven days after onset.About 1% of people with the disease die of it. In livestock, the fatality level is significantly higher. Pregnant livestock infected with RVF abort virtually 100% of foetuses. An epizootic (animal disease epidemic) of RVF is usually first indicated by a wave of unexplained abortions.

Other signs in livestock include vomiting and diarrhoea, respiratory disease, fever, lethargy, anorexia and sudden death in young animals.[3]

Cause

Virology

| Rift Valley fever phlebovirus | |

|---|---|

| Virus classification | |

| (unranked): | Virus |

| Realm: | Riboviria |

| Kingdom: | Orthornavirae |

| Phylum: | Negarnaviricota |

| Class: | Ellioviricetes |

| Order: | Bunyavirales |

| Family: | Phenuiviridae |

| Genus: | Phlebovirus |

| Species: | Rift Valley fever phlebovirus |

The virus belongs to the Bunyavirales order. This is an order of enveloped negative single stranded RNA viruses. All Bunyaviruses have an outer lipid envelope with two glycoproteins—G(N) and G(C)—required for cell entry. They deliver their genome into the host-cell cytoplasm by fusing their envelope with an endosomal membrane.

The virus' G(C) protein has a class II membrane fusion protein architecture similar to that found in flaviviruses and alphaviruses.[4] This structural similarity suggests that there may be a common origin for these viral families.

The virus' 11.5 kb tripartite genome is composed of single-stranded RNA. As a Phlebovirus, it has an ambisense genome. Its L and M segments are negative-sense, but its S segment is ambisense.[5] These three genome segments code for six major proteins: L protein (viral polymerase), the two glycoproteins G(N) and G(C), the nucleocapsid N protein, and the nonstructural NSs and NSm proteins.

Transmission

The virus is transmitted through mosquito vectors, as well as through contact with the tissue of infected animals. Two species—Culex tritaeniorhynchus and Aedes vexans—are known to transmit the virus.[6] Other potential vectors include Aedes caspius, Aedes mcintosh, Aedes ochraceus, Culex pipiens, Culex antennatus, Culex perexiguus, Culex zombaensis and Culex quinquefasciatus.[7][8][9] Contact with infected tissue is considered to be the main source of human infections.[10] The virus has been isolated from two bat species: the Peter's epauletted fruit bat (Micropteropus pusillus) and the aba roundleaf bat (Hipposideros abae), which are believed to be reservoirs for the virus.[11]

Pathogenesis

Although many components of the RVFV's RNA play an important role in the virus’ pathology, the nonstructural protein encoded on the S segment (NSs) is the only component that has been found to directly affect the host. NSs is hostile and combative against the hosts interferon (IFNs) antiviral response.[12] IFNs are essential in order for the immune system to fight off viral infections in a host.[13] This inhibitory mechanism is believed to be due to a number of reasons, the first being, competitive inhibition of the formation of the transcription factor.[12] On this transcription factor, NSs interacts with and binds to a subunit that is needed for RNA polymerase I and II.[12][14] This interaction cause competitive inhibition with another transcription factor component and prevents the assembly process of the transcription factor complex, which results in the suppression of the host antiviral response.[12][14] Transcription suppression is believed to be another mechanism of this inhibitory process.[12] This occurs when an area of NSs interacts with and binds to the host's protein, SAP30 and forms a complex.[12][14] This complex causes histone acetylation to regress, which is needed for transcriptional activation of the IFN promoter.[14] This causes IFN expression to be obstructed. Lastly, NSs has also been known to affect regular activity of double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase R.. This protein is involved in cellular antiviral responses in the host. When RVFV is able to enter the hosts DNA, NSs forms a filamentous structure in the nucleus. This allows the virus to interact with specific areas of the hosts DNA that relates to segregation defects and induction of chromosome continuity. This increases host infectivity and decreases the host's antiviral response.[12]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis relies on viral isolation from tissues, or serological testing with an ELISA.[3] Other methods of diagnosis include Nucleic Acid Testing (NAT), cell culture, and IgM antibody assays.[15] As of September 2016, the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) has developed a product called Immunoline, designed to diagnose the disease in humans much faster than in previous methods.[16]

Prevention

A person's chances of becoming infected can be reduced by taking measures to decrease contact with blood, body fluids, or tissues of infected animals and protection against mosquitoes and other bloodsucking insects. Use of mosquito repellents and bed nets are two effective methods. For persons working with animals in RVF-endemic areas, wearing protective equipment to avoid any exposure to blood or tissues of animals that may potentially be infected is an important protective measure.[17] Potentially, establishing environmental monitoring and case surveillance systems may aid in the prediction and control of future RVF outbreaks.[17]

No vaccines are currently available for humans.[17][1] While a vaccines have been developed for humans, it has only been used experimentally for scientific personnel in high-risk environments.[1] Trials of a number of vaccines, such as NDBR-103 and TSI-GSD 200, are ongoing.[18] Different types of vaccines for veterinary use are available. The killed vaccines are not practical in routine animal field vaccination because of the need of multiple injections. Live vaccines require a single injection but are known to cause birth defects and abortions in sheep and induce only low-level protection in cattle. The live-attenuated vaccine, MP-12, has demonstrated promising results in laboratory trials in domesticated animals, but more research is needed before the vaccine can be used in the field. The live-attenuated clone 13 vaccine was recently registered and used in South Africa. Alternative vaccines using molecular recombinant constructs are in development and show promising results.[17]

A vaccine has been conditionally approved for use in animals in the US.[19] It has been shown that knockout of the NSs and NSm nonstructural proteins of this virus produces an effective vaccine in sheep as well.[20]

Epidemiology

RVF outbreaks occur across sub-Saharan Africa, with outbreaks occurring elsewhere infrequently. In Egypt in 1977–78, an estimated 200,000 people were infected and there were at least 594 deaths.[21] [22] In Kenya in 1998, the virus killed more than 400 people. In September 2000, an outbreak was confirmed in Saudi Arabia and Yemen. On 19 October 2011, a case of Rift Valley fever contracted in Zimbabwe was reported in a Caucasian female traveler who returned to France after a 26-day stay in Marondera, Mashonaland East Province during July and August, 2011[23] but later classified as "not confirmed."[24]

Outbreaks of this disease usually correspond with the warm phases of the EI Niño/Southern Oscillation. During this time there is an increase in rainfall, flooding and greenness of vegetation index, which leads to an increase in mosquito vectors.[25] RVFV can be transmitted vertically in mosquitos, meaning that the virus can be passed from the mother to her offspring. During dry conditions, the virus can remain viable for a number of years in the egg. Mosquitos lay their eggs in water, where they eventually hatch. As water is essential for mosquito eggs to hatch, rainfall and flooding cause an increase in the mosquito population and an increased potential for the virus.[26]

2006/07 outbreak in Kenya and Somalia

In November 2006, a Rift Valley fever outbreak started in Kenya. The cases were from the North Eastern Province and Coast Province of Kenya, which had received heavy rain, causing floods and creating breeding grounds for mosquitoes, which spread the virus of the fever from infected livestock to humans.

By 7 January 2007, about 75 people had died and another 183 were infected.[27] The outbreak forced the closure of livestock markets in the North Eastern Province, affecting the economy of the region.[28]

The outbreak was subsequently reported to have moved into Maragua and Kirinyaga districts of Central Province of Kenya.[29]

On 20 January 2007, the outbreak was reported to have crossed into Somalia from Kenya and killed 14 people in the Lower Jubba region.[30]

As of 23 January 2007, cases had started to crop up at the Kenyan capital, Nairobi. Businesses were suffering large losses, as customers were shunning the common meat joints for the popular nyama choma (roast meat), as it was believed to be spreading the fever.

In December 2006 and again in January 2007, Taiwan International Health Action (Taiwan IHA) began operating missions in Kenya [31] consisting of medical experts assisting in training laboratory and health facility personnel, and included donations of supplies, such as mosquito sprays. The United States Centers for Disease Control also set up an assistance mission and laboratory in Kenya.

By the end of January, 2007, some 148 people had died since the outbreak began in December.

On 14 March 2007, the Kenyan government declared RVF cases to be diminished after spending an estimated $2.5 million in vaccine and deployment costs. It also lifted the ban on cattle movement in the affected areas. The final death toll in this outbreak was more than 150 people.[32]

However, on 8 June 2018, the Ministry of Health in Kenya declared another outbreak of RVF.[33]

2007 outbreak in Sudan

As of 2 November 2007, 125 cases, including 60 deaths, had been reported from more than 10 localities of White Nile, Sinnar, and Gezira states in Sudan. Young adult males were predominantly affected. More than 25 human samples have been found positive for RVF by PCR or ELISA.[34]

2010 South Africa outbreak

As of 8 April 2010, the Ministry of Health South Africa had reported 87 human cases infected with Rift Valley fever (RVF), including two deaths in Free State, Eastern Cape and Northern Cape provinces.[35] Most of these cases reported direct contact with RVFV-infected livestock and or were linked to farms with confirmed animal cases of RVF. The human cases were among farmers, veterinarians and farm workers. All cases were confirmed with RVF by test conducted at the National Institute of Communicable Diseases (NICD) in Johannesburg, South Africa.

An outbreak of Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) infection affected sheep, goats, cattle and wildlife on farms within Free State, Eastern Cape, Northern Cape, Western Cape, Mpumalanga, North West, and Gauteng provinces. As of 29 March 2010, about 78 farms reported laboratory-confirmed animal cases, with extensive livestock deaths.

Before the 2010 outbreak, sporadic cases of RVFV infection in animals had been documented in South Africa. The last major outbreak of the disease in humans occurred between 1974 and 1976, where an estimated 10,000 to 20,000 cases were recorded.[36]

2016 outbreak in Uganda

In March 2016, a male butcher from Kabale District in western Uganda reported to a local hospital with symptoms of headache, fever, fatigue and bleeding, subsequently testing positive for Rift Valley Fever. CDC sent epidemiologists to the District to assist the Ugandan Ministry of Health with the epidemiologic investigation of this small, localized outbreak of 3 confirmed and 2 probable cases. Working with the Uganda Virus Research Institute (UVRI) and the Uganda Ministry of Health, the CDC team conducted a serologic study in animals and humans and also assessed residents’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to Rift Valley Fever. The team collected samples from cows, goats and sheep, and interviewed and tested 650 district residents. A coordinated educational campaign targeting the general population, farmers, herders, and butchers was initiated and informational posters were created targeting these groups.[37]

2018 outbreak in Kenya

As of 16 June 2018, an outbreak of Rift Valley fever is ongoing in northern Kenya, with 26 suspected human cases including 6 deaths in Wajir County (24 cases) and Marsabit County (2 cases); 7 cases have been confirmed. There have also been numerous deaths and abortions in camels, goats and other livestock across a wider area of the country.[32]

2018–19 outbreak in Mayotte

As of 3 May 2019, an outbreak is ongoing in the French Mayotte Islands, part of the Comoro group off Mozambique. The first human case showed symptoms on 22 November 2018, and there have been a total of 129 confirmed human cases, as well as more than a hundred foci in livestock. The outbreak has led to restrictions on the sale of uncooked milk, as well as the sale and export of cattle and uncooked meat. WHO noted that mosquito transmission should decrease as the rainy season ends in April, although Cyclone Kenneth has been associated with increased rain.[38]

Biological weapon

Rift Valley fever was one of more than a dozen agents that the United States researched as potential biological weapons before the nation suspended its biological weapons program in 1969.[39][40]

Research

The disease is one of several identified by WHO as a likely cause of a future epidemic in a new plan developed after the Ebola epidemic for urgent research and development toward new diagnostic tests, vaccines and medicines.[41][42]

References

- "Rift Valley fever". Fact sheet N°207. World Health Organization. May 2010. Archived from the original on 15 April 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- Palmer SR (2011). Oxford textbook of zoonoses : biology, clinical practice, and public health control (2nd ed.). Oxford u.a.: Oxford Univ. Press. p. 423. ISBN 9780198570028. Archived from the original on 2017-09-08.

- Rift Valley Fever Archived 2012-05-08 at the Wayback Machine reviewed and published by WikiVet, accessed 12 October 2011.

- Dessau M, Modis Y (January 2013). "Crystal structure of glycoprotein C from Rift Valley fever virus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 110 (5): 1696–701. Bibcode:2013PNAS..110.1696D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1217780110. PMC 3562824. PMID 23319635.

- "ViralZone: Phlebovirus". viralzone.expasy.org. Archived from the original on 2016-10-03. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- Jupp PG, Kemp A, Grobbelaar A, Lema P, Burt FJ, Alahmed AM, Al Mujalli D, Al Khamees M, Swanepoel R (September 2002). "The 2000 epidemic of Rift Valley fever in Saudi Arabia: mosquito vector studies". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 16 (3): 245–52. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00371.x. PMID 12243225.

- Turell MJ, Presley SM, Gad AM, Cope SE, Dohm DJ, Morrill JC, Arthur RR (February 1996). "Vector competence of Egyptian mosquitoes for Rift Valley fever virus". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 54 (2): 136–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.136. PMID 8619436.

- Turell MJ, Lee JS, Richardson JH, Sang RC, Kioko EN, Agawo MO, Pecor J, O'Guinn ML (December 2007). "Vector competence of Kenyan Culex zombaensis and Culex quinquefasciatus mosquitoes for Rift Valley fever virus". Journal of the American Mosquito Control Association. 23 (4): 378–82. doi:10.2987/5645.1. PMID 18240513. S2CID 36591701.

- Fontenille D, Traore-Lamizana M, Diallo M, Thonnon J, Digoutte JP, Zeller HG (1998). "New vectors of Rift Valley fever in West Africa". Emerging Infectious Diseases. 4 (2): 289–93. doi:10.3201/eid0402.980218. PMC 2640145. PMID 9621201.

- Swanepoel R, Coetzer JA (2004). "Rift Valley fever". In Coetzer JA, Tustin RC (eds.). Infectious diseases of livestock (2nd ed.). Cape Town: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. pp. 1037–70. ISBN 978-0195761702.

- Boiro I, Konstaninov OK, Numerov AD (1987). "[Isolation of Rift Valley fever virus from bats in the Republic of Guinea]". Bulletin de la Société de Pathologie Exotique et de Ses Filiales (in French). 80 (1): 62–7. PMID 3607999.

- Boshra H, Lorenzo G, Busquets N, Brun A (July 2011). "Rift valley fever: recent insights into pathogenesis and prevention". Journal of Virology. 85 (13): 6098–105. doi:10.1128/JVI.02641-10. PMC 3126526. PMID 21450816.

- Fensterl V, Sen GC (2009-01-01). "Interferons and viral infections". BioFactors. 35 (1): 14–20. doi:10.1002/biof.6. PMID 19319841.

- Ikegami T, Makino S (May 2011). "The pathogenesis of Rift Valley fever". Viruses. 3 (5): 493–519. doi:10.3390/v3050493. PMC 3111045. PMID 21666766.

- Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley PM (2013). Fields Virology, 6th Edition. Philadelphia, PA, USA: Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 441. ISBN 978-1-4511-0563-6.

- "Kemri develops kit for rapid test of viral disease". Archived from the original on 2016-09-06. Retrieved 2016-09-14.

- "Prevention: Rift Valley Fever | CDC". US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- Fawzy M, Helmy YA (February 2019). "The One Health Approach is Necessary for the Control of Rift Valley Fever Infections in Egypt: A Comprehensive Review". Viruses. 11 (2): 139. doi:10.3390/v11020139. PMC 6410127. PMID 30736362.

- Ikegami T, Hill TE, Smith JK, Zhang L, Juelich TL, Gong B, Slack OA, Ly HJ, Lokugamage N, Freiberg AN (July 2015). "Rift Valley Fever Virus MP-12 Vaccine Is Fully Attenuated by a Combination of Partial Attenuations in the S, M, and L Segments". Journal of Virology. 89 (14): 7262–76. doi:10.1128/JVI.00135-15. PMC 4473576. PMID 25948740.

- Bird BH, Maartens LH, Campbell S, Erasmus BJ, Erickson BR, Dodd KA, Spiropoulou CF, Cannon D, Drew CP, Knust B, McElroy AK, Khristova ML, Albariño CG, Nichol ST (December 2011). "Rift Valley fever virus vaccine lacking the NSs and NSm genes is safe, nonteratogenic, and confers protection from viremia, pyrexia, and abortion following challenge in adult and pregnant sheep". Journal of Virology. 85 (24): 12901–9. doi:10.1128/JVI.06046-11. PMC 3233145. PMID 21976656.

- Arzt J, White WR, Thomsen BV, Brown CC (January 2010). "Agricultural diseases on the move early in the third millennium". Veterinary Pathology. 47 (1): 15–27. doi:10.1177/0300985809354350. PMID 20080480. S2CID 31753926.

- Bird BH, Ksiazek TG, Nichol ST, Maclachlan NJ (April 2009). "Rift Valley fever virus". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 234 (7): 883–93. doi:10.2460/javma.234.7.883. PMID 19335238. S2CID 16239209.

- Vesin G (19 October 2011). "Rift Valley Fever, human—France: ex Zimbabwe (Mashonaland East) first report". ProMED mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 20111020.3132. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015.

- Grandadam M, Malvy D (29 November 2011). "Rift Valley Fever, human—France: ex Zimbabwe (Mashonaland East) not". ProMED mail. International Society for Infectious Diseases. 20111129.3486. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015.

- Nanyingi MO, Munyua P, Kiama SG, Muchemi GM, Thumbi SM, Bitek AO, Bett B, Muriithi RM, Njenga MK (2015-07-31). "A systematic review of Rift Valley Fever epidemiology 1931-2014". Infection Ecology & Epidemiology. 5: 28024. doi:10.3402/iee.v5.28024. PMC 4522434. PMID 26234531. Archived from the original on 2016-12-02.

- "Rift Valley Fever | CDC". www.cdc.gov. Archived from the original on 2016-12-04. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- "At least 75 people die of Rift Valley Fever in Kenya". International Herald Tribune. 7 January 2007. Archived from the original on 9 January 2007.

- "Kenya: Schools Disrupted As Deadly Fever Hits Incomes". IRIN. 11 January 2007.

- "Nairobi at risk of RVF infection". The Standard (Kenya). 22 January 2007. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007.

- "14 die after Rift Valley Fever breaks out in southern Somalia". Shabelle Media Network, Somalia. 20 January 2007. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30.

- Issue Archived 2007-09-30 at the Wayback Machine. Mofa.gov.tw (2012-04-02). Retrieved on 2014-05-12.

- "Rift Valley fever – Kenya". WHO. 18 June 2018. Retrieved 1 July 2018.

- "WHO | Rift Valley fever – Kenya". WHO. Retrieved 2019-12-07.

- "Deadly fever spreads Kenya Panic". BBC. 26 January 2007. Archived from the original on 1 May 2008.

- ProMED-mail Archived 2011-07-28 at the Wayback Machine. ProMED-mail. Retrieved on 2014-05-12.

- "Rift Valley fever in South Africa". WHO. Archived from the original on 2010-04-12.

- "Outbreak Summaries | Rift Valley Fever | CDC". 2019-02-15.

- "Rift Valley Fever – Mayotte (France)". WHO. 13 May 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- "Chemical and Biological Weapons: Possession and Programs Past and Present", James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury College, April 9, 2002, accessed November 14, 2008.

- "Select Agents and Toxins" (PDF). USDA-APHIS and CDC: National Select Agent Registry. 2011-09-19. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-25.

- Kieny M. "After Ebola, a Blueprint Emerges to Jump-Start R&D". Scientific American Blog Network. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

- "LIST OF PATHOGENS". World Health Organization. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 13 December 2016.

External links

- CDC RVF Information Page

- Rift Valley Fever disease card at OIE

- "Rift Valley fever". Fact sheet N°207. World Health Organization. May 2010. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- "Rift Valley fever virus". NCBI Taxonomy Browser. 11588.

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |