Battle of Mutina

The Battle of Mutina took place on 21 April 43 BC between the forces loyal to the Senate under Consuls Gaius Vibius Pansa and Aulus Hirtius, supported by the legions of Caesar Octavian, and the Caesarian legions of Mark Antony which were besieging the troops of Decimus Brutus. The latter, one of Caesar's assassins, held the city of Mutina (present-day Modena) in Cisalpine Gaul.

| Battle of Mutina | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

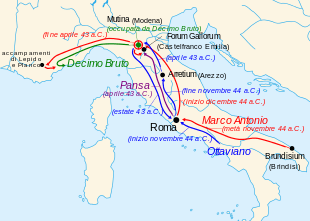

Map of the movements of the various legions during the campaigns leading up to the Battle of Mutina | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Senate | Mark Antony's forces | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Aulus Hirtius † Octavian Decimus Brutus Albinus | Mark Antony | ||||||

The battle took place after the bloody and uncertain Battle of Forum Gallorum had ended with heavy losses on both sides and the mortal wounding of Consul Vibius Pansa. Six days after Forum Gallorum, the other Consul Aulus Hirtius and the young Caesar Octavian launched a direct attack on the camps of Mark Antony in order to break the front of encirclement around Mutina. The fighting was very fierce and bloody; the Republican troops broke into the enemy's camps but Antony's veterans counterattacked. Hirtius himself was killed in the melee while attacking Antony's camp, leaving the army and republic leaderless. Octavian saw action in the battle, recovered Hirtius' body, and managed to avoid defeat. Decimus Brutus also participated in the fighting with part of his forces locked up in the city. Command of the deceased consul Hirtius' legions devolved to Caesar Octavian. Decimus Brutus, marginalized after the battle, soon fled Italy in the hopes of joining fellow assassins Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus. En route, however, Decimus Brutus was captured and executed, thus becoming the second of Caesar's assassins to be killed, after Lucius Pontius Aquila, who was killed during the battle.

After the battle, Mark Antony decided to give up the siege and skillfully retreated westward along the Via Aemilia, escaping the enemy forces and rejoining the reinforcements of his lieutenant Publius Ventidius Bassus. The battle of 21 April 43 BC brought the brief war of Mutina to a victorious end for the Republicans allied with Caesar Octavian, but the situation would change completely the following autumn with the formation of the Second Triumvirate of Antony, Octavian, and Lepidus.

Background

Mark Antony had dominated the political situation in Rome for only a short time after the assassination of Julius Caesar on 15 March 44 BC. An incongruous coalition among some of Caesar's assassins, the resurgent Senatorial faction led by Marcus Tullius Cicero, and the followers of the dictator's young heir, Caesar Octavian—the future emperor Augustus—had quickly caused difficulties for the consul Antony by eroding his consensus of support within the Caesarian camp.[1] Relations between the Roman Senate and Antony broke down entirely around one year after Julius Caesar's murder. Antony was unhappy with the province he was due to govern, Macedonia, after his one-year term as consul expired. Macedonia was too far away if trouble were to threaten him in the capital, Rome, so he sought to exchange the post for a five-year term in Cisalpine Gaul. From that region he could overawe the capital, and if need be intervene directly, as Caesar did in 44 BC. However, a different governor had already been selected for Cisalpine Gaul, namely Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, who was already in possession of the province with three legions with the consent of the Senate. Decimus Brutus was a distant relative of Marcus Junius Brutus and a one-time follower of Julius Caesar who had lost confidence in the dictator and taken part in his assassination on the Ides of March. Antony attempted to preempt the hostile attitude of his opponents by marching his legions of Caesarian veterans from Macedonia north to force Decimus Junius Brutus to surrender the province of Cisalpine Gaul to him.[2]

.jpg)

On 28 November 44 BC, Mark Antony left Rome and took command of four legions of veterans that had landed at Brundisium from Macedonia, as well as Legio V Alaudae, which had been deployed earlier along the Via Appia.[3] The cohesion of this force was, however, seriously compromised by the defection at Brundisium of two of the best Caesarian legions, the Martia and the IIII Macedonica, who abandoned the consul for young Caesar Octavian. Despite exhortations and punishments, Mark Antony could not restore discipline to these two legions, who buttressed the forces of Caesar's heir, which already included a substantial number of veterans recruited in Campania.[4] At the end of the year, Mark Antony reached Cisalpine Gaul with his three remaining legions and a legion of reactivated veterans.[5] As Decimus Brutus refused to abandon the province to him, Antony invested Mutina,[6] located just south of the Padus (Po) River on the Via Aemilia.

Meanwhile, in Rome, a formidable coalition was coming together in support of Decimus Brutus and in opposition to Antony, particularly since Cicero's return to the Senate in late 44 BC. Cicero delivered a series of increasingly uncompromising speeches against Antony, called the Philippics. On 1 January 43 BC, two moderate Caesarians, Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa, took office as consuls, whereupon the republican faction took the initiative, declaring Antony a public enemy, legalizing the actions of Decimus Brutus and Caesar Octavian, and recruiting new legions.[7]

Though Octavian had no love for Decimus Brutus, one of his adoptive father's assassins, he gained legitimacy by using his legions in support of the Senate against Antony. Therefore, after being appointed a propraetor by the Senate, he joined his forces with those of the new consul Hirtius, who had assumed command as Octavian's superior in January 43 BC at Ariminum, for the relief of Brutus. The forces of Caesar Octavian included the two legions that had defected and three legions of recalled veterans. From Ariminum, Hirtius and Octavian advanced along the Via Aemilia while Mark Antony continued to press the siege of Mutina.

On 19 March 43 BC, Pansa, the other new consul, was also sent north from Rome to join up with Hirtius (his fellow consul) and Octavian, at Forum Gallorum. Pansa had four legions of recruits.[8] Antony marched on 14 April with his praetorian cohort, the II and the XXXV legions, light-armed troops, and a strong body of cavalry to cut Pansa off before he could reach the senatorial armies. Antony assumed that Pansa had only four legions of raw recruits, but the previous night Hirtius had dispatched the Legio Martia and Octavian's praetorian cohort to assist Pansa. Antony prepared a deadly ambush against these hardened veterans, as well as Pansa's recruits,[9] in the marshes along the Via Aemilia. The Battle of Forum Gallorum[10] was fierce and bloody; Pansa's troops were routed and their commander mortally wounded. However, instead of gaining a decisive victory, Antony was forced to withdraw when a legion of reinforcements sent by Hirtius crashed into his own exhausted ranks.[11] This turned the fortunes of the battle. Antony's legions were beaten and retreated to Mutina.

Battle

Attack on the camps of Mark Antony

Initial news in Rome claimed that the Senate's forces had suffered a defeat at Forum Gallorum, arousing concern and fears among the Republican faction. Only on 18 April did they receive Aulus Hirtius' letter and a report detailing the events of the battle. The victory at Forum Gallorum, wrongly considered decisive, was greeted with enthusiasm; Antony was roundly denounced and his sympathizers forced into hiding. In the Senate on 21 April 43 BC, Cicero emphatically pronounced the Fourteenth and final Philippic, in which he exulted in the victory at Forum Gallorum, proposed forty days of public thanksgiving, and particularly praised the legionaries who had fallen and the two consuls Aulus Hirtius and Vibius Pansa. The latter was injured, but his life did not then seem in danger. The orator rather minimized the contribution of Caesar Octavian,[12] although the young man, despite his minor role in the battle, had been acclaimed imperator on the field by the troops, as had the two consuls Hirtius and Pansa.[13]

The Battle of Forum Gallorum appeared to decide the campaign in favour of the Senate's coalition. Mark Antony, after the losses he had suffered, had retreated with his surviving troops to his camp around Mutina and seemed determined to remain on the defensive. He had, however, strengthened the encircling front around Decimus Brutus in Mutina and continued to maintain his positions.[14] Mark Antony was by no means resigned to defeat, but for the time being he considered it dangerous to court another pitched battle against combined enemy forces that were numerically superior to his own. Instead, he intended to harass and weaken the armies of Hirtius and Octavian with continuous cavalry skirmishes. In this way he hoped to gain time and increase the pressure on Decimus Brutus, whose besieged troops in Mutina were now short of supplies.[15] The consul Hirtius and propraetor Octavian, confident after the victory of Forum Gallorum and reassured by the discipline of their Caesarian legions, were determined to force a new struggle to rescue Decimus Brutus and break the siege of Mutina.[16] After trying unsuccessfully to force Antony into open battle, the two commanders manoeuvred with their troops and concentrated the legions in a field where the enemy camps were less strongly fortified due to the characteristics of the ground.[15]

On 21 April 43 BC, Hirtius and Octavian launched their attack, trying to force a passage for supply columns to the besieged city.[16] Mark Antony initially sought to avoid a general battle and to respond to the challenge with only his cavalry, but when the enemy's cavalry units opposed him, he could not avoid committing his legions to the fray.[15] Antony therefore, in order to keep his siege lines from breaking, ordered up two of his legions to stem the advance of Hirtius and Octavian's massed forces.[16]

Now that the Antonian forces were finally out in the open field, Aulus Hirtius and Caesar Octavian concentrated their legions to attack them. A fierce battle commenced outside the camps. Mark Antony transferred additional forces to meet the onslaught. According to Appian, at this stage of the battle the Antonian forces found themselves struggling mainly because of the slow arrival of their reinforcements; the legions who were caught by surprise and deployed far from the area where the most important clashes were going on, entered the field late and Octavian's forces seemed to have the best of the fighting.[15]

Death of Aulus Hirtius

While this battle was raging outside the camps, the consul Hirtius took the bold decision to break directly into the camp of Antony with some of his forces. The consul then personally led the Legio III into the camp, making directly for Mark Antony's personal tent.[15] At the same time, Decimus Brutus had finally organized a sortie with some of his cohorts who, under the command of Lucius Pontius Aquila (another of Caesar's assassins), came out of Mutina and attacked the camp of Antony.[16] At first, Hirtius' action appeared successful: the Legio III, after breaking through, fought near Antony's tent; the consul led the legionaries on the frontline; meanwhile, the battle continued in other areas as well. Soon, however, the situation deteriorated for the troops that had beset the camps. Mark Antony's Legio V, which defended the camp, opposed the Legio III, and after an awkward and bloody melee managed to halt its advance, protecting their commander's tent. During the confusion of this fighting, Aulus Hirtius was killed and his legion seemed to be forced to retreat from the ground it had won.[16] As the Legio III began to fold under the Antonian counterattack, other troops led by Caesar Octavian came to their relief. Caesar's young heir found himself in the midst of the fiercest clashes and fought violently to recover Hirtius' body.[15] According to Suetonius, "in the thick of the fight, when the eagle-bearer of his legion was sorely wounded, he shouldered the eagle and carried it for some time."[17]

Octavian eventually managed to recover the consul's remains, but could not keep possession of the camps. In the end, his legions retreated from Antony's camp. At the culminating moment of the battle, Pontius Aquila was killed, and his troops, which had made a sortie out of the city, eventually returned to Mutina.[16] On the basis of the reconstructions of ancient historians it is difficult to know precisely the true course of the final clashes of the battle, pro-Augustan accounts exalting the role of Octavian and his courageous action to recover the body of the consul Hirtius.[18] Other sources cast doubts on the real actions of the young heir of Caesar; Suetonius[19] and Tacitus[20] report other versions that hint that Hirtius was even dispatched during the melee by Octavian himself in his eagerness to get rid of an uncomfortable political rival. The death of Pontius Aquila, a fierce opponent of the Caesarian faction, has also appeared suspect to some historians.[21]

By virtue of his imperium as propraetor, Caesar Octavian assumed command of Hirtius' legions. When the Senate ordered that the legions be handed over to Decimus Brutus, Octavian refused, assuming permanent command on the grounds that the established legions would refuse to fight under the command of one of Julius Caesar's assassins. As a result, Octavian came to control eight legions, loyal to himself rather than to the Republic. He refused to co-operate with Decimus Brutus, whose legions at Mutina began deserting him, many going over to Octavian. His position deteriorating by the day, Decimus Brutus abandoned his remaining legions and fled Italy. He attempted to reach Macedonia, where fellow assassins Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus were stationed, but was captured and executed en route by a Gallic chief loyal to Mark Antony.

Mark Antony's retreat

The Battle of Mutina ended without a clear victor. Mark Antony, though in serious difficulty under the attacks of the superior enemy forces, had not been annihilated, and the two sides suffered nearly equal casualties.[22] However, the very night of the battle, Antony summoned a war council and determined that further resistance would be useless, despite his lieutenants' exhortations that he renew the attack, taking advantage of his superiority in cavalry and the exhaustion of Decimus Brutus's supplies.[22]

Antony probably did not know about the death of Hirtius or understand the weakness of the legions left to Octavian's command. Rather than contemplating a decisive counterattack, Antony feared a renewed attack on his own camps.[23] He therefore adopted Julius Caesar's expedient after the failure at the Battle of Gergovia and abandoned the siege, hoping to join up with the legions that Ventidius Bassus was bringing from Picenum.[24] Having reconcentrated his forces, he proceeded to march to the Alps to communicate with the Caesarian leaders Marcus Aemilius Lepidus in Gallia Narbonensis and Lucius Munatius Plancus in Gallia Comata. After making his decision, Mark Antony acted swiftly and effectively: the very night after the battle, he sent a message instructing Ventidius Bassus to march quickly through the Apennines and join him with his three legions. He then abandoned the siege on the morning of 22 April 43 BC, retiring with all his surviving forces.[24] In a few days, marching west along the Via Aemilia, his legions reached first Parma and then Placentia without difficulty, for his opponents had remained in Mutina, leaving Antony to gain two days' advantage.[25] Arriving at Tortona, Mark Antony decided to turn southwards and crossed his four legions over the Apennines. In this way, he reached the coast of Liguria west of Genoa at Vada Sabatia, where on 3 May 43 BC, he was joined by Ventidius Bassus with three legions.[26] Antony's lieutenant had not encountered any check to his progress through the mountains to the Ligurian coast; thus, Antony's manoeuvre to extricate himself from Mutina and regrouping proved successful.[26]

Aftermath and assessment

The victory of the Senatorial forces and the allied faction of young Caesar Octavian at the Battle of Mutina did not decisively put an end to Mark Antony's hostility, who, in a timely and successful retreat, was able to cheat the victors of success in the campaign. The eventual turnaround in Antony's fortunes was facilitated by the breakdown of the precarious alliance between Octavian and the Republican faction led by Cicero. Following the death of Aulus Hirtius in battle on the night of 22–23 April, the consul Vibius Pansa also died as a result of the wounds he had suffered at Forum Gallorum. In this case, too, the circumstances of his death remained obscure and rumours spread, according to Suetonius and Tacitus, that Pansa had been poisoned, with hints that the ambitious Octavian might be implicated.[27]

After the death of the two consuls, Caesar Octavian was left alone at the helm of the Senate's legions. Mutina is essentially where Octavian turns from an inferior young man to an equal of Antony. He immediately adopted an attitude of opposition to Decimus Brutus, refusing any co-operation with this murderer of Caesar.[28] In Rome, Cicero and his supporters in the Senate dismayed Octavian by minimizing his role and assigning the supreme command in the war against Antony to Decimus Brutus alone. Brutus' plans to pursue the enemy were, however, thwarted by the obstructionism of Octavian, who, in command of eight legions at Bononia, did not march to the Apennines to block Ventidius Bassus, as Caesar's assassin had intended.[29] Within a few weeks Mark Antony, strengthened by the legions of Ventidius Bassus, reached the Alps and concluded a formidable alliance with the Caesarian commanders Lepidus, Lucius Munatius Plancus, and Gaius Asinius Pollio,[30] assembling an army of 17 legions and 10,000 cavalry (in addition to six legions left behind with Varius, according to Plutarch). Decimus Brutus, abandoned by his legions and forced to flee to Macedonia, would later be killed by Celtic warriors sent to pursue him by Antony, while Caesar Octavian was eventually to march with his troops on Rome, forcing the Ciceronian faction in the Senate into submission or exile.[31] Following a face-to-face meeting near Bononia in October, Mark Antony, Caesar Octavian, and Lepidus concluded a formal pact. This resulted in their legally becoming the Commission of Three for the Ordering of the State, more commonly known as the Second Triumvirate, through the Lex Titia promulgated in Rome on 27 November 43 BC. The three Caesarian leaders solemnly entered the capital, assumed full political control, and ruthlessly pursued their opponents in the republican faction.[32] Cicero, who was killed on the orders of Antony, was the most high-profile victim of the triumvirate's proscriptions.[33]

In the power struggles ensuing many years later, Octavian would eventually defeat Antony and Cleopatra at Actium in 31 BC and usher in the Principate, but Mutina was the milestone where Octavian first established himself as a force to be reckoned with. Without this victory, Octavian might never have attained the prestige necessary to be looked upon as Caesar's successor, and the stability of the Empire might never have been established in the lasting manner which Octavian had decided for it.

Notes

- Syme (2014), pp. 110–136.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 23–24.

- Ferrero (1946), pp. 100.

- Syme (2014), pp. 140–142.

- Appian, III, 46.

- Syme (2014), pp. 142–143.

- Syme (2014), pp. 187–188.

- Syme (2014), pp. 189–193.

- Ferrero (1946), p. 211.

- Oddly, Ovid Fasti 4.627-28 lists 14 April as date of the battle at which Caesar defeated the foe (Antony) at Mutina, but at Tristia 4.10.10–14, the poet lists his own birthday as 20 March – thought to be the exact day of the Battle of Mutina, and he says exactly one year after his brother's birthday. Apparently Ovid was not born on the very day of the battle.

- Ferrero (1946), pp. 212–213.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 42–44.

- Syme (2014), p. 193.

- Ferrero (1946), pp. 213–214.

- Appian, III, 71.

- Ferrero (1946), p. 214.

- Suetonius, Life of Augustus 10.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 48–49.

- Suetonius, Life of Augustus 11.

- Tacitus, Annals I.10.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 49, 54–55.

- Appian, III, 72.

- Ferrero (1946), pp. 214–215.

- Ferrero (1946), p. 215.

- Syme (2014), p. 196.

- Syme (2014), p. 199.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 53–55.

- Canfora (2007), pp. 62–63.

- Syme (2014), pp. 197–198.

- Syme (2014), pp. 199–201.

- Syme (2014), pp. 205–206.

- Syme (2014), pp. 210–213.

- Syme (2014), p. 214.

References

Ancient sources

- Appian of Alexandria. Historia Romana (Ῥωμαϊκά) (in Ancient Greek). Civil Wars, book III.

- Cassius Dio Cocceianus. Historia Romana (in Ancient Greek). Book XXXXVI.

Modern sources

- Bleicken, Jochen (1998). Augustus. Berlin: Fest. ISBN 3-8286-0136-7.

- Canfora, Luciano (2007). La prima marcia su Roma. Bari: Editori Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-8970-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ferrero, Guglielmo (1946). Grandezza e decadenza di Roma. Volume III: da Cesare a Augusto. Cernusco sul Naviglio: Garzanti.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fields, Nic (2018). Mutina 43 BC: Mark Antony's struggle for survival. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-4728-3120-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Syme, Ronald (2002). The Roman Revolution. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-1928-0320-7.

- Syme, Ronald (2014). La rivoluzione romana. Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-22163-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (Italian translation)

External links

- Jon Day, "Operation Columba" (review of Gordon Corera, Secret Pigeon Service, William Collins, 2018, 326 pp., ISBN 978 0 00 822030 3), London Review of Books, vol. 41, no. 7 (4 April 2019), pp. 15–16. "Pigeons flew across the Roman Empire carrying messages from the margins to the capital. [In 43 BCE] Decimus Brutus broke Marc Antony's siege of Mutina by sending letters to the consuls via pigeon. 'What service,' Pliny wrote, 'did Antony derive from his trenches, and his vigilant blockade, and even from his nets stretched across the river, while the winged messenger was traversing the air?'" (Jon Day, p. 15.)