Roman–Latin wars

The Roman–Latin wars were a series of wars fought between ancient Rome (including both the Roman Kingdom and the Roman Republic) and the Latins, from the earliest stages of the history of Rome until the final subjugation of the Latins to Rome in the aftermath of the Latin War.

First war with Rome

The Latins first went to war with Rome in the 7th century BC during the reign of the Roman king Ancus Marcius.

According to Livy the war was commenced by the Latins who anticipated Ancus would follow the pious pursuit of peace adopted by his grandfather, Numa Pompilius. The Latins initially made an incursion on Roman lands. When a Roman embassy sought restitution for the damage, the Latins gave a contemptuous reply. Ancus accordingly declared war on the Latins. The declaration is notable since, according to Livy, it was the first time that the Romans had declared war by means of the rites of the fetials.[1]

Ancus Marcius marched from Rome with a newly levied army and took the Latin town of Politorium by storm. Its residents were removed to settle on the Aventine Hill in Rome as new citizens, following the Roman traditions from wars with the Sabines and Albans. When the other Latins subsequently occupied the empty town of Politorium, Ancus took the town again and demolished it.[2] Further citizens were removed to Rome when Ancus conquered the Latin towns of Telleni and Ficana.[2]

The war then focused on the Latin town of Medullia. The town had a strong garrison and was well fortified. Several engagements took place outside the town and the Romans were eventually victorious. Ancus returned to Rome with much loot. More Latins were brought to Rome as citizens and were settled at the foot of the Aventine near the Palatine Hill, by the temple of Murcia.[2]

War with Rome under Tarquinius Priscus

When Rome was ruled by Lucius Tarquinius Priscus the Latins went to war with Rome on two occasions.

On the first, which according to the Fasti Triumphales occurred prior to 588 BC, Tarquinius took the Latin town of Apiolae by storm, and from there brought back a great amount of loot to Rome.[3]

On the second occasion, Tarquinius subdued the entirety of Latium, and took a number of towns that belonged to the Latins or which had revolted to them: Corniculum, old Ficulea, Cameria, Crustumerium, Ameriola, Medullia and Nomentum, before agreeing to peace.[4]

War between Clusium and Aricia

In 508 BC, Lars Porsena king of Clusium (at that time reputed to be one of the most powerful cities of Etruria) departed Rome after ending his war against Rome by peace treaty. Porsena split his forces, and sent part of the Clusian army with his son Aruns to besiege the Latin city of Aricia. The Aricians sent for assistance from the Latin League, and also from the Greek city of Cumae. When support arrived, the Arician army ventured beyond the walls of the city, and the combined armies met the Clusian forces in battle. According to Livy, the Clusians initially routed the Arician forces, but the Cumaean troops allowed the Clusians to pass by, then attacked from the rear, gaining victory against the Clusians. Livy says the Clusian army was destroyed.[5]

The Pometian revolt

In 503 BC two Latin towns, Pometia and Cora, said by Livy to be colonies of Rome, revolted against Rome. They had the assistance of the southern Aurunci tribe.

Livy says that a Roman army led by the consuls Agrippa Menenius Lanatus and Publius Postumius Tubertus met the enemy on the frontiers and was victorious, after which Livy says the war was confined to Pometia. Livy says many enemy prisoners were slaughtered by each side.[6] Livy also says that the consuls celebrated a triumph, however the Fasti Triumphales record that an ovation was celebrated by Postumius and a triumph by Menenius, both over the Sabines.

In the following year the consuls were Opiter Virginius and Sp. Cassius. Livy says that they attempted to take Pometia by storm, but then resorted to siege engines. However the Aurunci launched a successful sally, destroying the siege engines, wounding many, and nearly killing one of the consuls. The Romans retreated to Rome, recruited additional troops, and returned to Pometia. They rebuilt the siege engines and when they were about to take the town, the Pometians surrendered. The Aurunci leaders were beheaded, the Pometians sold into slavery, the town razed and the land sold. Livy says the consuls celebrated a triumph as a result of the victory.[7] The Fasti Triumphales record only one triumph, by Cassius (possibly over the Sabines although the inscription is unclear).

The battle of Lake Regillus and the foedus Cassianum

In 501 BC word reached Rome that thirty of the Latin cities had joined in league against Rome, at the instigation of Octavius Mamilius of Tusculum. Because of this (and also because of a dispute with the Sabines), Titus Lartius was appointed as Rome's first dictator, with Spurius Cassius as his magister equitum.[8]

However war with the Latins did not come to pass until at least two years later.

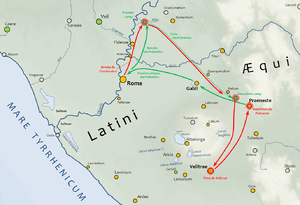

In 499 BC, or possibly 496 BC, war broke out. At first Fidenae was besieged (although it is not clear by whom), Crustumerium was captured (again it is not clear by whom), and Praeneste defected to the Romans. Aulus Postumius was appointed dictator, with Titus Aebutius Elva as his magister equitum. With the Roman army, they marched into the Latin territory and were victorious at the Battle of Lake Regillus.[9]

Shortly afterwards, in 495 BC, the Latins resisted calls from the Volsci to join with them to attack Rome, and went so far as to deliver the Volscian ambassadors to Rome. The Roman senate, in gratitude, granted freedom to 6,000 Latin prisoners, and in return the Latins sent a crown of gold to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus in Rome. A great crowd formed, including the freed Latin prisoners, who thanked their captors. Great bonds of friendship were said to have arisen between the Romans and the Latins as a result of this event. The Latins also warned Rome of the Volscian invasion which occurred shortly after in the same year[10]

In 493 a treaty, the Foedus Cassianum, was concluded, establishing a mutual military alliance between the Latin cities with Rome as the leading partner. A second people, the Hernici, joined the alliance sometime later. While the precise workings of the Latin League remains uncertain, its overall purpose seems clear. During the 5th century the Latins were threatened by invasion from the Aequi and the Volsci, as part of a larger pattern of Sabellian-speaking peoples migrating out of the Apennines and into the plains. Several peripheral Latin communities appear to have been overrun, and the ancient sources record fighting against either the Aequi, the Volsci, or both almost every year during the first half of the 5th century. This annual warfare would have been dominated by raids and counter-raids rather than the pitched battles described by the ancient sources.

Defection of the Latins from Rome (389–385)

In 390 a Gaulish warband first defeated the Roman army at the Battle of the Allia and then sacked Rome. According to Livy the Latins and Hernici, after a hundred years of loyal friendship with Rome, used this opportunity to break their treaty with Rome in 389.[11] In his narrative of the years that followed, Livy describes a steady deterioration of relations between Rome and the Latins. In 387 the situation with Latins and Hernici was brought up in the Roman senate, but the matter was dropped when news reached Rome that Etruria was in arms.[12] In 386 the Antiates invaded the Pomptine territory and it was reported in Rome that the Latins had sent warriors to assist them. The Latins claimed they had not sent aid to the Antiates, but had not prohibited individuals from volunteering for such service.[13] A Roman army under Marcus Furius Camillus and P. Valerius Potitus Poplicola met the Antiates at Satricum. In addition to Volscians the Antiates had brought a large number of Latins and Hernicians to the field.[14] In the battle that followed the Romans were victorious and the Volscians were slaughtered in great number. The Latins and Hernicians now abandoned the Volscians, and Satricum fell to Camillus.[15] The Romans demanded to know from the Latins and Hernici why for the last few years' wars they had not furnished any contingents. They claimed not to have been able to supply troops due to fear of Volscian incursions. The Roman senate considered this defence to be insufficient, but that time was not right for war.[16] In 385 the Romans appointed Aulus Cornelius Cossus Dictator to deal with the Volscian war.[17] The Dictator marched his army into the Pomptine territory, which he had heard was being invaded by the Volscians.[18] The Volscian army was once again swelled by Latins and Hernici, including contingents from the Roman colonies of Circeii and Velitrae, and in the battle that followed the Romans were once again victorious. The majority of the captives were found to be Hernici and Latins, including men of high rank, which the Romans took as proof that their states were formally assisting the Volscians.[19] However the sedition of Marcus Manlius Capitolinus prevented Rome from declaring war on the Latins.[20] When the Latins, Hernici, and the colonists of Circeii and Velitrae tried to persuade the Romans to release those of their countrymen who had been made prisoner, they were refused.[21] That same year Satricum was colonized with 2,000 Roman citizens, each to receive two and a half jugera of land.[22]

Some modern historians have questioned Livy's portrayal of the Latins as rebelling from Rome. Cornell (1995) believes that there was no armed uprising of Latins, rather the military alliance between Rome and the other Latin towns seems to have been allowed to wither. In the preceding decades Rome had grown considerably in power, especially with the conquest of Veii, and the Romans might now have preferred freedom of action to the obligations of the alliance. Also, several Latin towns appear to have remain allied to Rome; based on later events these would have included at least Tusculum and Lanuvium to which Cornell adds Aricia, Lavinium and Ardea. The colonies of Circeii and Velitrae are likely to have remained partly inhabited by Volsci, which helps explain their rebellion, but these two settlements more than any other Latin towns would have felt vulnerable to Rome's aggressive designs for the Pomptine region.[23]

Division among the Latins is also the stance taken by Oakley (1997) who substantially accepts Cornell's analysis. The continued loyalty of Ardea, Aricia, Gabii, Labicum, Lanuvium and Lavinium would help explain how Roman armies could operate in the Pomptine region.[24] In their writings on the early Roman Republic Livy and Dionysius of Halicarnassus often mention men from states formally at peace with Rome fighting in the armies of Rome's enemies in a private capacity. Though this might genuinely reflect Italic warfare of this era, Livy appears here to be using it as a literary motif to bring continuity to his narrative of the 380s.[25]

War between Rome and Praeneste (383–379)

In the last years of the 380s Praeneste emerged as the leading Latin city in opposition to Rome. In terms of territory Praeneste was the third largest city in Latium, but between 499 and 383 Praeneste is wholly absent from the sources and much of the fighting against the Aequi by Rome and the Latin League appear to have taken place to the south of her territory. Modern historians have therefore proposed that Praeneste was overrun or at least came to some kind of understanding with the Aequi. If this was the case Praeneste would not have been part of the Latin League for most of the 5th century. The end of the Aequan threat by the early 4th century freed Praeneste to move against Rome.[26][27]

Outbreak

Livy records that in 383 Lanuvium, which had so far been loyal to Rome, rebelled. In Rome, on the advice of the senate, the tribes unanimously declared for war on Velitrae after five commissioners had been appointed to distribute the Pomptine territory and three to settle a colony at Nepete. However, there was pestilence in Rome throughout the year and no campaign was launched. Among the revolting colonists a peace party was in favour of asking Rome for pardon, but the war party continued to hold the population's favour and a raid was launched into Roman territory, effectively ending all talk of peace. There was also a rumour that Praeneste had revolted, and the peoples of Tusculum, Gabii and Labici complained that their territories had been invaded, but the Roman senate refused to believe these charges.[28] In 382 consular tribunes Sp. and L. Papirius marched against Velitrae, their four colleagues being left to defend Rome. The Romans defeated the Veliternian army, which included a large number of Praenestine auxiliaries, but refrained from storming the place, doubting whether a storm would be successful and not wanting to destroy the colony. Based on the report of the tribunes, Rome declared war on Praeneste.[29]

Of all the old Latin towns, Lanuvium was closest to Pomptine plain; it is therefore no surprise that she now joined the struggle against Rome.[30] Rumours of wars about to break out are common in Livy's writings, but of doubtful historicity; such rumours would have been easy inventions for the annalists seeking to bring life to their narratives. However, some of them may be based on authentic records; if this is the case here, it may represent an attempt by Praeneste to win over the Latin cities still loyal to Rome.[31] While the details provided by Livy for the campaign of 382 are plausible, the original records likely only stated there was fighting against Praeneste and Velitrae.[32]

Livy and Plutarch provide parallel narratives for 381. In that year the Volsci and Praenestines are said to have joined forces and, according to Livy, successfully stormed the Roman colony of Satricum. In response the Romans elected M. Furius Camillus as consular tribune for the sixth time. Camillus was assigned the Volscian war by special senatorial decree. His fellow tribune L. Furius Medullinus was chosen by lot to be his colleague in this undertaking.[33] There are some differences between Livy and Plutarch in their accounts of the campaign that followed. According to Livy the tribunes marched out from the Esquiline Gate for Satricum with an army of four legions, each consisting of 4000 men. At Satricum they met an army considerably superior in number and eager for battle. Camillus however refused to engage the enemy, seeking instead to protract the war. This exasperated his colleague, L. Furius, who claimed that Camillus had become too old and slow and soon won over the whole army to his side. While his colleague prepared for battle, Camillus formed a strong reserve and awaited the outcome of the battle. The Volsci started to retire soon after the battle had started, and, as they had planned, the Romans were drawn into following them up the rising ground toward the Volscian camp. Here the Volsci had placed several cohorts in reserve and these joined the battle. Fighting uphill against superior numbers, the Romans started to flee. However Camillus brought up the reserves and rallied the fleeing soldiers to stand their ground. With the infantry wavering, the Roman cavalry, now led by L. Furius, dismounted and attacked the enemy on foot. As a result, the Volsci were defeated and fled in panic, and their camp was taken. A large number of Volsci were killed and an even larger number taken prisoners.[34] According to Plutarch, a sick Camillus was waiting in the camp while his colleague engaged the enemy. When he heard that Romans had been routed, he sprung from his couch, rallied the soldiers and stopped the enemy pursuit. Then, on the second day, Camillus led his forces out, defeated the enemy in battle and took their camp. Camillus then learned that Satricum had been taken by the Etruscans and all the Roman colonists there slaughtered. He sent the bulk of his forces back to Rome, while he and the youngest men fell upon the Etruscans and expelled them from Satricum.[35]

Of the two versions of this battle that have been preserved, Plutarch's is thought to be closer to the earlier annalists than that of Livy. Notably, Livy presents a more noble picture of Camillus than Plutarch, and he has also compressed all the fighting into one day rather than two.[36] That the Praenestines should have joined with the Volsci at Satricum and been defeated there by Camillus is credible enough; however, most, if not all, the details surrounding the battle, including the supposed quarrel between Camillus and L. Furius, are today considered to be later inventions. Especially the scale of the battle and the Roman victory have been vastly exaggerated.[32]

Roman annexation of Tusculum

Having described Camillus' victory against the Volsci, Livy and Plutarch move on to a conflict with Tusculum. According to Livy, Camillus found Tusculans among the prisoners taken in the battle against the Volscians. Camillus brought these back to Rome, and after the prisoners had been examined, war was declared on Tusculum.[37] According to Plutarch, Camillus had just returned to Rome with the spoils when it was reported that the Tusculans were about to rebel.[38] The conduct of the war was entrusted to Camillus, who chose L. Furius as his colleague. Tusculum, however, offered no resistance whatsoever, and when Camillus entered the city he found everyone going about their daily life as if there was no war. Camillus ordered the leading men of Tusculum to go to Rome and plead their case. This they did with the dictator of Tusculum as the spokesman. The Romans granted Tusculum peace and not long after full citizenship.[39]

By 381 Tusculum was almost surrounded by Roman territory and her annexation was a logical step for Rome. Besides increasing Roman territory and manpower, this had the additional benefit of separating Tibur and Praeneste from the cities on the Alban hills.[40] Tusculum became the first Roman municipium, a self-governing city of Roman citizens. Some modern historians have argued that this episode has been invented or is a retrojection of later events. Cornell (1995) Oakley (1998) and Forsythe (2005) accept the incorporation of Tusculum in 381 as historical.[40][41] Livy and other later writers portrayed the annexation of Tusculum as a benevolent act, but this view more properly reflect their own times, when Roman citizenship was highly sought after. In the 4th century when the Latin cities struggled to maintain their independence from Rome, it would have been seen as an aggressive act. Later events reveal that Tusculum was not yet firmly in Roman hands.[42] In the Roman period the chief magistrates of Tusuclum had the title of aedile, but it is possible, as Livy claims, that in 381 Tusculum was governed by a dictator.[43]

Dictatorship of T. Quinctius Cincinnatus

Livy provides the only full narrative for 380. After a failed census in Rome, the plebeian tribunes started agitating for debt relief and obstructed the enrollment of fresh legions for the war against Praeneste. Not even the news that the Praenestines had advanced into the district of Gabii deterred the tribunes. Learning that Rome had no army in the field, the Praenestine army pushed on until it stood before the Colline Gate. Alarmed, the Romans appointed T. Quinctius Cincinnatus as Dictator with A. Sempronius Atratinus as his Master of the Horse and assembled the army. In response the Praenestines withdrew to the Allia where they set up camp, hoping that memories of their earlier defeat against the Gauls at the same place would cause dread among the Romans. The Romans, however, recalled their previous victories against the Latins and relished the chance of wiping out previous defeats. The Dictator ordered A. Sempronius to charge the Praenestine center with the cavalry; the Dictator would then attack the disordered enemy with the legions. The Praenestines broke at the first charge. In the panic they abandoned their camp, the flight not stopping until they were within sight of Praeneste. At first unwilling to abandon the countryside to the Romans, the Praenestines established a second camp, but on the arrival of the Romans this second camp was also abandoned and the Praenestines retreated behind the walls of their city. The Romans first captured eight towns subordinated to Praeneste and then marched on Velitrae which was stormed. When the Roman army arrived before Praeneste the Praenestines surrendered. Having defeated the enemy in battle and captured two camps and nine towns, Titus Quinctius returned to Rome in triumph, carrying with him from Praeneste a statue of Jupiter Imperator. This statue was set up on the Capitol between the shrines of Jupiter and Minerva with the inscription "Jupiter and all the gods granted that the dictator Titus Quinctius should capture nine towns". Titus Quinctius laid down his office on the twentieth day after his appointment.[44] According to D.H. and Festus the nine towns were captured in nine days.[45] Festus further adds that Quinctius captured Praeneste on the tenth and dedicated a golden crown weighing two and one third of a pound.[46] D.S. also records a Roman victory in battle against the Praenestines in this year, but does not provide any details.[47] According to Livy, the next year, 379, the Praenestines renewed hostilities by instigating revolts among the Latins;[48] however, apart from this notice Praeneste is not mentioned again in the sources until 358.

Modern historians generally accept the core of Livy's account of Titus Quinctius' dictatorship and its dating to 380. Thus that he captured nine towns subordinated to Praeneste and forced the Praenestines to sue for peace is considered historical.[49] Oakley (1998) also believes Quinctius' victory in pitched battle could be historical, and maybe also his capture of Velitrae as well. No fighting is reported against Velitrae until 369, but this could also be a later invention. However, the claims that the Praenestines marched on Rome via Gabii and the placement of the battle at the Allia are of very doubtful historicity.[50] With regards to the discrepancies between Livy and Festus, Oakley believes that Festus, while mistaken when claiming that Praeneste was stormed, was correct in stating that T, Quinctius dedicated a crown rather than, more magnificently, bringing back a statue from Praeneste. Titus Quinctius Flamininus is said to have brought back a statue of Jupiter from Macedonia after his victories in the Second Macedonian War two centuries later and these two events have become then confused.[51] This view is accepted by Forsythe (2005).[52] Forsythe considers T. Quinctius Cincinnatus' inscription to be origin of the more famous, but in Forsythe's view fictitious, story of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus' dictatorship and victory against the Aequi in 458 BC.[53]

Destruction of Satricum (377)

According to Livy, in 377 the Volsci and Latins united their forces at Satricum. The Roman army, commanded by consular tribunes P. Valerius Potitus Poplicola and L. Aemilius Mamercinus, marched against them. The battle that followed was interrupted on the first day by a rainstorm. On the second the Latin resisted the Romans for some time, being familiar with their tactics, but a cavalry charge disrupted their ranks and when the Roman infantry followed up with a fresh attack they were routed. The Volsci and Latins retreated first to Satricum and thence to Antium. The Romans pursued, but lacked the equipment to lay siege to Antium. After a quarrel whether to continue the war or sue for peace, the Latin forces departed and the Antiates surrendered their city to the Romans. In fury the Latins set fire to Satricum and burned the whole city down except the temple of Mater Matuta – a voice coming from the temple is said to have threatened terrible punishment if the fire was not kept away from the shrine. Next the Latins attacked Tusculum. Taken by surprise, the whole city fell except the citadel. A Roman army under consular tribunes L. Quinctius Cincinnatus and Ser. Sulpicius Rufus marched to the Tusculans' relief. The Latins attempted to defend the walls, but caught between the Roman assault and the Tusculans sallying from the citadel they were all killed.[54]

Mater Matuta was a deity originally connected with the early morning light, and the temple at Satricum was the chief centre of her cult.[55] However, Livy also records the burning of Satricum, except the temple of Mater Matuta, in 346, this time by the Romans. Modern historians agree that this twice burning of Satricum in 377 and 346 is a doublet. Beloch, believing that the Romans would not have recorded a Latin attack on Satricum, considered the burning in 377 a retrojection of the events of 346. Oakley (1997) takes the opposite view, believing that the ancient historians are less likely to have invented the burning by the Latins than the burning by the Romans. Though the twice miraculous saving of the temple is discarded as a doublet, it does not automatically follow that hotly contested Satricum could not have been captured both in 377 and 346.[56] Latin displeasure with Tusculum's annexation by Rome could explain why they might also have acted in support of an anti-Roman revolt.[57]

War between Rome and Tibur (361–354)

Tibur was one of the largest Latin cities, but is only scarcely attested in the sources. Like Praeneste, Tibur might therefore have been overrun or detached from the Latin League by the Aequi in the 5th century.[58] Livy then records a long war between Rome and Tibur lasting from 361 to 354. Two triumphs connected to this war are recorded in the Fasti Triumphales. From a notice in Diodorus Siculus, it appears that also Praeneste was at war with Rome in this time period, but, except in connection with the Gallic invasion of 358, Praeneste is nowhere mentioned in Livy's account of this time period.[59]

Tibur allies with the Gauls

According to Livy the immediate cause for this war came in 361 when the Tiburtes closed their gates against a Roman army returning from a campaign a Q. Servilius Ahala as dictator. The dictator defeated the Gauls in a battle near the Colline Gate. The Gauls fled towards Tibur, but were intercepted by the consul. The Tiburtes sallied in a failed attempt to assist their allies, and both the Tiburtes and Gauls were driven within the gates. The dictator praised the consuls and laid down his office. Poetilius celebrated a double triumph over the Gauls and the Tiburtes, but the Tiburtes belittled the achievements of the Romans.[60] The Fasti Triumphales records that C. Poetelius Libo Visolus, consul, celebrated a triumph over the Gauls and Tiburtes on 29 July. According to Livy in 359 the Tiburtes marched at night against the City of Rome. The Romans were at first alarmed, but when daylight revealed a comparatively small force, the consuls attacked from two separate gates and the Tiburtines were routed.[61]

There are some inconsistencies in what caused the war between Rome and Tibur, and much of the details for these years are likely invented. The historicity of this Gallic war is itself somewhat dubious; this, along with the fact that both Livy and F.T. assign the triumph to the consul, have led to doubts about the historicity of Servilius' dictatorship as well.[62]

Renewed alliance between Roman and the Latins

In 358 Latium was again threatened by invasion from the Gauls. Livy records that the Romans granted a new treaty to the Latins on their request. The Latins sent a strong contingent to fight against the Gauls, who had reached Praeneste and settled in the country round Pedum, in accordance with the old treaty which for many years had not been observed.[63] Led by the Roman dictator C. Sulpicius Peticus, the Roman-Latin army defeated the Gauls. In this year Rome also established the Pomptina tribe.[64]

We have no knowledge precisely who these Latins were, or if they had been at war with Rome in the preceding years. The other Latin states cannot have been pleased with the now-permanent Roman presence in the Pomptine region, but the seriousness of the Gallic threat would have provided motive for resuming their alliance with Rome. However, Tibur and Praeneste evidently remained hostile to Rome.[65] None of the other Latin states are recorded as hostile to Rome and presumably continued to supply contingents after 358, and this might be one of the reasons behind the increased pace of Roman expansion during the 350s and 340s.[66]

Conclusion of the war

Livy only provides brief descriptions of the final years of this war. In 356, consul M. Popilius Laenas commanded against the Tiburtes. He drove them into their city and ravaged their fields.[67] In 355, the Romans took Empulum from the Tiburtes without serious fighting. According to some of the writers consulted by Livy, both consuls, C. Sulpicius Peticus and M. Valerius Poplicola, commanded against the Tiburtes; according to others, it was only Valerius, while Sulpicius campaigned against the Tarquinienses.[68] Then, in 354, the Romans took Sassula from Tibur. After this, the Tiburtes surrendered and the war was brought to a conclusion. A triumph was celebrated against the Tiburtes.[69] The Fasti Triumphales records that M. Fabius Ambustus, consul, triumphed over the Tiburtes on 3 June. D.S. records that Rome made peace with Praeneste this year.[70]

This is the only recorded mention of Empulum and Sassula. They must have been small towns located in territory controlled by Tibur, but their precise locations are unknown. Modern historians consider the capture of such obscure sites unlikely to be invented; they might here ultimately derive from pontifical records of captured towns.[71] While not all the fighting recorded in this war appears to have been very serious, Tribur and Praeneste must have been worn down by continuous warfare when they sued for peace in 354. They are not heard from again before the outbreak of the great Latin War in 340.[72]

The Latin War (340–338)

With the Latin War the Latins and the Volsci made a final bid to shake off Roman dominion. Once again Rome was victorious. In the peace settlement that followed, Rome annexed some states outright, while others remained autonomous Latin states, but the Latin League was dissolved. Instead the surviving Latin states were bound to Rome by separate bilateral treaties. The Campanians, who had sided with the Latins, were organized as civitas sine suffragio – citizenship without a vote – which gave them all the rights and duties of a Roman citizen, including that of military service, except the right to vote in the Roman assemblies. This peace settlement was to become a template for how Rome later dealt with other defeated states.

References

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:32

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:33

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:35

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1:38

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.14

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.16

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.17

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2:18

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2:19–20

- Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.22, 24

- Livy, 6.2.3–4; Plutarch, Camillus 33.1 (who does not mention the Hernici)

- Livy, 6.6.2–3

- Livy, 6.6.4–5

- Livy, 7.7.1

- Livy, 6.8.4–10

- Livy, 6.10.6–9

- Livy, 6.11.9

- Livy, 6.12.1

- Livy, 6.12.6–11 & 6.13.1–8

- Livy, 6.14.1

- Livy, 6.17.7–8

- Livy, 6.15.2

- Cornell, T. J. (1995). The Beginnings of Rome- Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC). New York: Routledge. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7.

- Oakley, S. P. (1997). A Commentary on Livy Books VI-X, Volume 1 Introduction and Book VI. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 353–356. ISBN 0-19-815277-9.

- Oakley, pp. 446–447

- Cornell, pp. 306, 322–323

- Oakley, p. 338

- Livy, 6.21.2–9

- Livy, 6.22.1–3

- Cornell, p. 322

- Oakley, pp. 356, 573–574

- Oakley, p. 357

- Livy, 6.22.3–4; Plutarch, Camillus 37.2

- Livy, 6.22.7–24.11

- Plutarch, Camillus 37.3–5

- Okley, p. 580

- Livy, 6.25.1–5

- Plutarch, Camillus 38.1

- Livy, 6.25.5–26.8; D.H. xiv 6; Plutarch, Camillus 38.1–4; Cass. fr. 28.2

- Cornell, p. 323, Oakley p. 357

- Forsythe, Gary (2005). A Critical History of Early Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 257. ISBN 0-520-24991-7.

- Cornell, p. 323-324, Oakley p. 357

- Oakley p. 603-604

- Livy, 6.27.3–29.10

- D.H., XIV 5

- Fest. 498L s.v. trientem tertium

- D.S, xv.47.8

- Livy, 6.30.8

- Cornell, p. 323; Oakley, p. 358; Forsythe, p. 258

- Oakley, pp. 358, 608–609

- Oakley, p. 608

- Forsythe, p. 258

- Forsythe, p. 206

- Livy, 6.32.4–33.12

- Oakley, pp. 642–643

- Oakley, p. 352

- Oakley, p. 359

- Oakley, S. P. (1998). A Commentary on Livy Books VI-X, Volume 2 Books VII-VII. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 111–112. ISBN 978-0-19-815226-2.

- Oakley, p. 5-6

- Livy, 7.11.2–11

- Livy, 7.12.1–5

- Oakley, pp. 7, 151

- Livy, 7.12.7

- Livy, 7.15.12

- Cornell p.324; Oakley, p. 5

- Oakley, p. 7

- Livy, 7.17.2

- Livy, 7.18.1–2

- Livy, 7.19.1–2

- D.S., xvi.45.8

- Oakley, pp. 6, 193, 196; Forsythe p. 277

- Oakley, p. 6