Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement

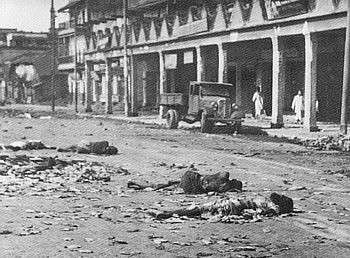

The Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement refers to the movement of the Bengali Hindu people for the Partition of Bengal in 1947 to create a homeland aka West Bengal for themselves within the Indian Union, in the wake of Muslim League's proposal and campaign to include the entire province of Bengal within Pakistan, which was to be a homeland for the Muslims of British India. The movement began in late 1946, especially after Direct Action Day in Kolkata and the Noakhali riots, gained significant momentum in April, 1947 and in the end met with success on 20 June 1947 when the legislators from the Hindu majority areas returned their verdict in the favour of Partition.

Background

| Part of a series on |

| Persecution of Bengali Hindus |

|---|

Part of Bengali Hindu history |

| Discrimination |

| Persecution |

|

| Opposition |

Deterioration of law and order

The law and order situation had rapidly deteriorated in Kolkata after the riots. When the Inspector General of Police asked for 50% increase in the Calcutta Armed Police Force, the Prime Minister Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy insisted that the new recruits must all be Punjabi Muslims to which Governor Frederick Burrows readily agreed.[1][2] To speed up training they must be ex-servicemen. As suitable candidates were not found in Bengal, 600 Punjabi Muslims were recruited from the Punjab. When the new recruits were given preferential treatment by the Muslim League government, the existing Gurkha policemen resented and the former engaged themselves in an armed conflict with the Gurkha policemen.

The Muslim police used to enter Bengali Hindu households and molest women. On 12 April, the police entered a Bengali Hindu household in Manicktala and beat up the residents. One, Chhayalata Ghosh, who was pregnant at that time, was severely injured.[3] News spread out that on 14 April another Bengali Hindu housewife was raped by the police.[3] Another such incident which took place on 100, Harrison Road, grabbed the headlines for quite some time. The Calcutta Riot Enquiry Committee observed that the police used to arrest young Bengali Hindu boys, so as to prevent them from appearing before the Committee in order to provide evidence. The Deputy Police Commissioner of Kolkata, Shams-ud-Doha systematically arrested Hindu youths upon identification by one single Muslim. He believed he would teach Hindus a lesson that way.

The Muslim League government imposed pre-censorship on news comments criticizing the police excesses. Through a special ordinance, the government imposed penalties on Hindu-owned media like Amrita Bazar Patrika, Hindustan Standard, Anandabazar Patrika and Modern Review and their security deposits confiscated.[3]

In certain towns of eastern Bengal, Bengali Hindu girls, in order to defend themselves, began to carry sharp weapons resembling bagh nakh, hidden in their dresses, while going to school.[4]

Mood of the Bengali Hindu people

On 5 March, Kiran Shankar Roy met Fredrick Burrows, the then Governor of Bengal. When the latter asked Roy about the Bengali Hindu opinion on the question of a sovereign united Bengal, Roy summed up that the Bengali Hindu resentment towards the Muslim League government was so high that it was possible that they would build up a passive resistance to the move, refuse to pay taxes to the Muslim League government and set up parallel government of their own.

According to Sir Chandulal Tribedi, Hindus in Bengal didn't want an independent Bengal.

Campaign

.jpg)

According to historian Amalendu De, the partition of Bengal was demanded for the first time by the Bengal Provincial Hindu Mahasabha during the Kolkata riots. But according to historian Dinesh Chandra Sinha, the West Bengal Provincial Committee was set up a few months before the Great Calcutta Killings, for the purpose of agitating for the partition of Bengal.[5] Towards the end of 1946, the Bengal Partition League was formed by eminent Bengali Hindu intellectuals as an association for the partition of Bengal. The key people among them were Hemanta Kumar Sarkar, Nalinakshya Sanyal, Major General A. C. Chatterjee, Jadab Panja, Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, Upendranath Banerjee, Dr. Shishir Kumar Banerjee, Subhodh Chandra Mitra and Shailendra Kumar Ghosh. The Bengal Partition League later came to be known as the Bengal Provincial Conference.[6] In February, the Bengal Provincial Hindu Mahasabha constituted a committee for the creation of a separate province for the Hindus of Bengal and began their campaign in the districts. On 29 March, at the annual meeting of the British Indian Association a proposal was passed for the constitution of a homeland for the Bengali Hindus. Maharaja Udaychand Mehtab of Burdwan, P.N.Sinha Ray, Maharaja Srish Chandra Nandy of Cossimbazar, Maharaja Prabendra Mohan Tagore, Maharaja Sitangshukanta Acharya Chaudhuri, Amulyadhan Auddy and Amarendra Narayan Roy were among the eminent persons who supported the move.[7]

Political

Early in February, the Bengal Hindu Sabha constituted a committee for the creation of a separate province for the Hindus of Bengal and began campaigning in the districts. In the first week of April, it convened a three-day-long Bengal Hindu Conference at Tarakeswar, starting on the 4th and attended by over 400 delegates from all over Bengal and over 50,000 people. In his presidential address on the first day of the conference, Nirmal Chandra Chatterjee lauded the successful agitation against Curzon's Partition of Bengal as the most outstanding chapter in the history of Bengal. He said the British had resorted to the partition of the province in order "to cripple the greatest nationalist force working for Independence of the country by making the Bengal Hindus minorities in both the provinces". The reason for demanding partition now, he explained, was to sustain Bengali Hindu nationalism, carve out a separate homeland for the Bengali Hindu people and constitute it as a province within India, and preserve the Bengali culture and heritage.[8] He further emphasized that it was a question of life or death for the Bengali Hindus. On 5 April, Syama Prasad, in his speech at the Bengal Hindu Conference at Tarakeshwar, suggested the partition of Bengal as the only solution to the communal problem. On the concluding day of the conference, the proposal of the partition was formally raised on behalf of the Bengal Hindu Sabha by Sanat Kumar Raychaudhuri and Surya Kumar Bose. At resolution was passed at the Bengal Hindu Conference at Tarakeswar, authorizing Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee to constitute a council of action in order to establish a separate homeland for the Bengali Hindus. It was decided that 100,000 volunteers would be enrolled for the purpose by the end of June. The Constituent Assembly was to be requested to appoint a boundary commission for the partition of the province.

On 4 April, the very day the Bengal Hindu Conference was under progress in Tarakeswar, the working committee of the Bengal Congress passed a resolution demanding the partition of Bengal. The meeting was attended by Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, Kshitish Chandra Niyogi, Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy, Nalini Ranjan Sarkar, Dr. Pramathanath Banerjee, Debendra Lal Khan, Makhanlal Sen and Atul Chandra Gupta among others. After this, the Bengal Hindu Sabha and the Congress intensified their campaigns. No less than 76 Partition meetings were held, of which 59 were convened by the Congress, 12 by the Mahasabha and five jointly.

Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee further clarified that the movement for the partition of Bengal was not directly related to the partition of India. Even if Pakistan was not created, it was necessary to partition Bengal for the safety of the Bengali Hindu people and their culture. On 22 April, at a public rally in New Delhi, Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee declared that even if the Muslim League accepts the Cabinet Mission plan, a separate province needs to be constituted in the Hindu majority areas of Bengal. Syama Prasad Mookerjee called a general strike in Bengal on 23 April demanding against the inclusion of the whole of Bengal into Pakistan. The strike was initially supported by the Communist Party of India. Later the tram workers union, owing affiliation to the CITU planned to defy the strike. When the news reached him, Syama Prasad Mookerjee himself toured the tram depots in person and successfully motivated the tram workers in favour of the strike.[9]

The Bengal Provincial Depressed Classes League too supported the partition of Bengal. The BPDCL secretary R. Das clarified that the Jogendranath Mandal's views are not supported by the majority.

Media

According to Dr. Dinesh Chandra Sinha, the Roy's Weekly suggested the division of Bengal to solve the communal problem for the first time.[10] After that Professor Hemanta Kumar Sarkar wrote a series of articles in Dainik Basumati, a Bengali daily, proposing the creation of a separate province of West Bengal.[10] After the Great Calcutta Killings in August, 1946, the correspondence columns of The Statesman and Amrita Bazar Patrika were opened to writers for and against the partition.[10] In December, 1946, Prabasi, a Bengali weekly commented that, chances of reconciliation and co-operation between the two communities are slim. It is time for due consideration of the proposal for partition of Bengal.[11][12] Sajanikanta Das, the editor of Shanibarer Chithi, a Bengali weekly noted that the Bengali Hindu Homeland Movement was being led by Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, Major General A.C.Chatterjee and Dr. Pramathanath Banerjee, therefore one can be rest assured that they would leave no stone unturned to achieve it.[10] In April, 1947, Sajanikanta Das opined in Shanibarer Chithi that it is in the best of interests to part ways.[11] On 23 April, Amrita Bazar Patrika published an article titled, Homeland for Bengali Hindus[5] where the results of a gallop poll were published. The survey revealed that an overwhelming 98.3% of the Bengali Hindus wanted the partition of Bengal and creation of a separate Bengali Hindu homeland.[12][13][14] On 24 April, The Statesman commented that the resentment among the middle class Bengali Hindus towards the Muslim League government was so high that nothing less than Partition would satisfy them.[15] Amrita Bazar Patrika subsequently constituted the Bengal Partition Fund, a public fund for the realization of the Bengali Hindu homeland.[12][16][17]

Intellectuals

On 15 March, Syama Prasad Mookerjee convened a meeting in Kolkata, attended by leading intellectuals like Dr. Ramesh Chandra Majumder, Dr. Makhanlal Raychaudhuri, Dr. Suniti Kumar Chattopadhyay, Pandit Ramshankar Tripathi among others.[18] At the meeting Shyama Prasad explained that, from the past experiences it is now clear that Hindus would not be able to live with honour and dignity in Pakistan. Therefore, unless a homeland for the Bengali Hindus is carved out, they would not be able to seek proper rehabilitation. In his speech Dr. Suniti Kumar Chattopadhyay seconded Shyama Prasad's proposal for a separate Bengali Hindu homeland.[19] At the conference it was declared that out of 106 proposals received from the different parts of the province, only six were against the partition of the province, while the overwhelming 94.33% were for creation of homeland for the Bengali Hindu people.[19] On 7 May, eminent Bengali Hindu intellectuals like Dr. Meghnad Saha, Dr. Jadunath Sarkar, Dr. Ramesh Chandra Majumder and Dr. Suniti Kumar Chattopadhyay demanded a separate homeland for the Bengali Hindu people on the ground of security.[11] In May, both the Hindu Mahasabha and Congress jointly convened a mammoth public meeting, presided over by historian Dr. Jadunath Sarkar, to press for Partition.

Judiciary

The jurists of the Kolkata High Court realized the need for a separate homeland for the Bengali Hindus. Otherwise, they felt, the Bengali Hindus would only exchange one form of slavery for another. 50 jurists signed a statement demanding the partition of Bengal.

Lobbying

On 1 April, 11 members of the Constituent Assembly from Bengal submitted a memorandum to the Viceroy, in support of the Partition. On 23 April, Syama Prasad Mookerjee met Viceroy Mountbatten and explained that if the Cabinet Mission plan failed and British India was to be partitioned, then Bengal should also be partitioned. On 26 April, both Kiran Shankar Roy and Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy assured Dr. Syama Prasad Mookerjee, that they would convince the Congress Working Committee of the need of partition of Bengal. On 3 May, two Scheduled Caste representatives of the Constituent Assembly from eastern Bengal met Viceroy Mountbatten at a party and stated that the Scheduled Castes were determined not to be left under the brutal suppression and domination of Muslims. They firmly demanded the partition of Bengal and suggested that the seven million Scheduled Castes should be relocated in the proposed Bengali Hindu homeland in western Bengal.

Outside support

On 30 April, the meeting of the Chambers of Commerce held at Kolkata lent the support for the Partition of Bengal. According to G.D.Birla, Partition was not only unavoidable, but an excellent way to solve the communal problem. The Muslim owned businesses too wanted Bengal to be partitioned because they wanted to free themselves from the unequal competition with the Tatas and the Birlas.

Aftermath

On 28 June 1947, Frederick Burrows, the Governor of Bengal invited Dr. Prafulla Chandra Ghosh, the leader of the Congress Assembly Party in Bengal to form a cabinet without portfolios and formal administrative powers.[20] The ministers of the cabinet would have the right to access to all the government papers and comment thereupon. They would also have the right to object to any proposal that affected the non-Muslim majority areas of the province.[20] The Bengali Hindu leadership and the press strongly criticized this arrangement as it meant that the Muslim League ministry would still continue hold the office. On 29 June, the Congress and the Muslim League high commands in New Delhi decided that the Muslim League government would continue in Bengal, but with limited powers that would allow them to legislate only for the Muslim-majority districts of eastern Bengal.[21] On the other hand, the Congress Assembly Party in Bengal would nominate a shadow cabinet to administer the Hindu-majority districts of western Bengal.[21] Accordingly, on 2 July, Dr. Prafulla Chandra Ghosh announced an eleven-member cabinet with portfolios. The cabinet included Scheduled Caste members Hem Chandra Naskar, in charge of Agriculture, Forest & Fisheries and Radhanath Das, in charge of Civil Supplies.[20]

Timeline

- 15 March, Bengal Hindu Conference held at Kolkata.

- 29 March, British Indian Association passes a resolution for the formation of a Bengali Hindu homeland.

- 1 April, 11 members of the Bengal Constituent Assembly submit a memorandum to the Viceroy demanding the Partition of Bengal.

- 4 April, Bengal Partition Convention held at Tarakeshwar.

- 23 April, Transport strike in Kolkata in favour of Partition of Bengal.

- 4 May, 2,000 rallies are simultaneously held across Bengal for the partition of the province.

- 7 May, conference in Kolkata in favour of partition.

- 3 June, Mountbatten announces plan for the Partition of Bengal.

- 20 June, Hindu legislators of the Bengal Legislative Assembly vote in favour of the Partition of Bengal.

References

- Chakrabarty, Bidyut (2004). The Partition of Bengal and Assam 1932-47. New Delhi: Routledge Curzon. p. 108.

- Sinha, Dinesh Chandra (2001). শ্যামাপ্রসাদ: বঙ্গভঙ্গ ও পশ্চিমবঙ্গ [Shyamaprasad: Banga Bibhag O Paschimbanga] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Akhil Bharatiya Itihash Sankalan Samiti. p. 250.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sandip (2010). ইতিহাসের দিকে ফিরে: ছেচল্লিশের দাঙ্গা [The Calcutta Riots, 1946] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Radical. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-85459-07-3.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sandip (2010). ইতিহাসের দিকে ফিরে: ছেচল্লিশের দাঙ্গা [The Calcutta Riots, 1946] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Radical. p. 71. ISBN 978-81-85459-07-3.

- Sinha, Dinesh Chandra (2001). শ্যামাপ্রসাদ: বঙ্গভঙ্গ ও পশ্চিমবঙ্গ [Shyamaprasad: Banga Bibhag O Paschimbanga] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Akhil Bharatiya Itihash Sankalan Samiti. p. 317.

- Sanyal, Sunanda; Basu, Soumya (2011). The Sickle & the Crescent: Communists, Muslim League and India's Partition. London: Frontpage Publications. p. 154. ISBN 978-81-908841-6-7.

- Sinha, Dinesh Chandra (2001). শ্যামাপ্রসাদ: বঙ্গভঙ্গ ও পশ্চিমবঙ্গ [Shyamaprasad: Banga Bibhag O Paschimbanga] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Akhil Bharatiya Itihash Sankalan Samiti. p. 275.

- Chatterji, Joya (2002). Bengal divided: Hindu communalism and partition, 1932-1947. Cambridge University Press. p. 241. ISBN 0-521-52328-1. Retrieved 20 March 2011.

The most glorious chapter in the history of Bengal is the agitation against the Partition imposed by British Imperialism. [It] was a fight against Imperialism which wanted to cripple the greatest nationalist force working for Independence of the country by making the Bengal Hindus minorities in both the provinces. Our demand for partition today is prompted by the same ideal and same purpose, namely, to prevent the disintegration of the nationalist element and to preserve Bengal's culture and to secure a Homeland for the Hindus of Bengal which will constitute a National State as a part of India. (Presidential address by N. C. Chartered at the Tarakeswar session of the Bengal Provincial Hindu Conference, 4 April 1947.)

- Das, Shyamalesh (1997). দূরদর্শী রাজনীতিক ডঃ শ্যামাপ্রসাদ [Dr Shyamapasad: The Foresighted Statesman] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Shreebhumi Publishing Company. pp. 69–70.

- Sinha, Dinesh Chandra (2001). শ্যামাপ্রসাদ: বঙ্গভঙ্গ ও পশ্চিমবঙ্গ [Shyamaprasad: Banga Bibhag O Paschimbanga] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Akhil Bharatiya Itihash Sankalan Samiti. p. 276.

- Das, Shyamalesh (1997). দূরদর্শী রাজনীতিক ডঃ শ্যামাপ্রসাদ [Dr Shyamapasad: The Foresighted Statesman] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Shreebhumi Publishing Company. p. 72.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sandip (2010). ইতিহাসের দিকে ফিরে: ছেচল্লিশের দাঙ্গা [The Calcutta Riots, 1946] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Radical. p. 74. ISBN 978-81-85459-07-3.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (1997). Caste, Protest and Identity in Colonial India: The Namasudras of Bengal, 1872-1947. Routledge. p. 225. ISBN 0-7007-0626-7.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar. "Changing Borders, Shifting Loyalties: Religion, Caste and the Partition of Bengal in 1947" (PDF). Asian Studies Institute Working Paper 2. Asian Studies Institute (1998): 5. Retrieved 16 March 2011.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2007). Bengal Divided - The Unmaking of a Nation (1905-1971). New Delhi: Penguin Books India. p. 148. ISBN 978-0-670-99913-2.

- Sen, Shila (1977). Muslim Politics in Bengal, 1937-47. New Delhi: Impex India. p. 227.

- Amrita Bazar Patrika. 28 May 1947. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Das, Shyamalesh (1997). দূরদর্শী রাজনীতিক ডঃ শ্যামাপ্রসাদ [Dr Shyamapasad: The Foresighted Statesman] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Shreebhumi Publishing. p. 70.

- Das, Shyamalesh (1997). দূরদর্শী রাজনীতিক ডঃ শ্যামাপ্রসাদ [Dr Shyamapasad: The Foresighted Statesman] (in Bengali). Kolkata: Shreebhumi Publishing Company. p. 71.

- Bandyopadhyay, Sekhar (19 August 2004). Caste, Culture and Hegemony: Social Dominance in Colonial Bengal. SAGE. p. 230. ISBN 9780761998495. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- Chatterji, Joya (15 November 2007). The Spoils of Partition: Bengal and India, 1947–1967. Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9781139468305. Retrieved 9 April 2017.