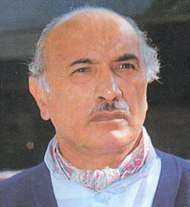

Asghar Khan

Mohammad Asghar Khan (Urdu: اصغر خان 17 January 1921 – 5 January 2018), was a Pakistani politician and an autobiographer, later a dissident serving the cause of pacifism, peace, and human rights.[3]

Asghar Khan | |

|---|---|

Asghar Khan (1921–2018) | |

| President of Pakistan International Airlines | |

| In office 20 August 1965 – 30 November 1968 | |

| Preceded by | Mirza Ahmad Ispahani |

| Succeeded by | Air-Mshl. Nur Khan |

| Director-General of the Civil Aviation Authority | |

| In office 1965–1968 | |

| Commander in Chief of Pakistan Air Force | |

| In office 23 July 1957 – 22 July 1965 | |

| President | Ayub Khan (1960–65) Iskander Mirza (1956–59) |

| Deputy | Air-Mshl. Sharbat Changezi (Deputy Air Cdr-in-C) |

| Preceded by | AVM Arthur McDonald |

| Succeeded by | AM. Nur Khan |

| Chairman of the Solidarity Movement | |

| In office 29 June 1970 – 12 December 2011 | |

| Preceded by | Party established |

| Succeeded by | Imran Khan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Mohammad Asghar Khan 17 January 1921 Jammu, Kashmir, British India (Present day in Jammu in Jammu and Kashmir in India) |

| Died | 5 January 2018 (aged 96) Combined Military Hospital in Rawalpindi, Punjab in Pakistan |

| Cause of death | Cardiac arrest |

| Resting place | Abottabad, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan |

| Citizenship | British India (1921–1947) Pakistan (1947–2018) |

| Political party | Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf |

| Other political affiliations | National Democratic Party |

| Children | Nasreen, Shereen, Omar and Ali Asghar |

| Civilian awards | |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Shaheen-i-Pakistan Night Flyer |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1939–68[2] |

| Rank | |

| Unit | 9th Deccan Horse, Armored Corps |

| Commands | Pakistan Air Force Academy Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force, Air AHQ Peshawar Air Force Base No. 9 Squadron, RIAF |

| Battles/wars | World War II First Burma Campaign Second Burma Campaign |

| Military awards | |

Born into a military family, Asghar Khan briefly served as an officer in the Indian Army before being deputed to the Royal Indian Air Force (IAF) as a military adviser in 1941— he was later drafted into the IAF as its commanding officer on the Asian front of World War II.[4] After the Partition of India In 1947, Khan chose to join the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) and later secured promotion as a three star rank air officer when he was appointed in 1957 as Commander-in-chief to command the PAF at the age of 36 – the youngest officer at the command level in the Pakistani military at that time. In 1965, his dissent with General Musa Khan, the Army Commander in Chief, over the Operation Gibraltar area contingency plans, and vetoing decisions to go on the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, eventually led to his replacement with Air Marshal Malik Nur Khan.[3] Asghar Khan continued to serve with his rank when he was deputed as a Pakistan International Airlines's executive, until retiring in 1968.[2]

After his retirement from the military in 1968, Asghar Khan founded the Tehrik-e-Istiqlal (Solidarity Party) with a secular and centrist political program in direct opposition to the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and the Pakistan Muslim League (PML), but failed to make any significant impact in the 1970 Pakistani general elections. From the 1970s–90s, Khan's political career focused towards the 'Dharna' or 'politics of agitation', against the elected civilian governments, and gained notability when he filed multiple lawsuits, over the Mehrangate bank scandal, against the PPP and the PML(N) at the Supreme Court of Pakistan in the 1990s.[5] During this time, Khan authored many political books, some very critical or given dissenting criticism of the Pakistan Army's involvement in national politics.[6][7]

In 2011, Khan merged his party with the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (Pakistan Movement for Justice).[8] Khan died in January 2018 and was buried with state honours.[9]

Biography

Family background, early life and military career in India

Mohammad Asghar Khan was born in Jammu, Kashmir in the British Indian Empire on 17 January 1921 into a Pashtun family.[10]:iii[4] His family belonged to an Afridi tribe from the Tirah Valley in the tribal-belt region, that settled in Jammu and Kashmir.[4] His father, Brigadier Thakur Rehmatullah Khan, was an army officer in the Jammu and Kashmir Rifles of the British Indian Army, and later emigrated to Abbottabad after the Partition of British India in 1947.[11][12]

His elder brother, Brigadier Aslam Khan, was a one-star rank army general in the Pakistan Army who earned his reputation as the "Legend of Baltistan" after his participation in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948, Pakistan's first war with India.[13]

After his education at a boarding school, Asghar Khan was sent to attend the Royal Indian Military College in 1933 where he secured his matriculation in 1939, subsequently joining the British Indian Army in 1939.:67[14] After graduating from the Indian Military Academy 1940, he gained a commission in the British Indian Army as the Second lieutenant in the Royal Deccan Horse attached to the Armoured Corps of the Indian Army in December 1940.[15] In 1941, Lieutenant Asghar Khan was seconded to the Royal Indian Air Force, joining the No. 9 Squadron as its military adviser during the Burma fronts.:15[16][4] In 1942, Captain Khan was transferred to the Royal Indian Air Force, where he saw actions in the first front in Burma against Japan, and flew bomber missions in the Hawker Hurricane.:14[17]

In 1944, Squadron Leader (Sq Ldr.) Khan later served in the second front in Burma, commanding the No. 9 Squadron alongside Sq Ldr. Arjan Singh who led the No. 1 Squadron during the aerial operations of the Arakan Campaign 1942–43.:content[4]

After the end of World War II in the Pacific, Sq Ldr. Khan was posted to the Ambala Air Force Station where he was assigned as the flight instructor at the Flying Instructors School until 1947.:15[16] He was noted to be the first Indian to have qualified to fly the Gloster Meteor jet fighter, in the United Kingdom in 1946.[4]

During this time, Sq Ldr. Khan decided to transfer to the Pakistan Air Force and went to Great Britain to attend the RAF Staff College at Bracknell, where he graduated in 1949.[4] He was later directed to attend the Joint Service Defence College located in Latimer, Buckinghamshire and graduated in 1952.:v[10] He continued his further education at the Imperial Defence College and graduated in 1955.:v[10][4]

Command and war appointments in the Pakistani military

Upon returning to Pakistan Wing Commander (Wg-Cdr.) Asghar was appointed as the first Commandant of the Pakistan Air Force Academy in Risalpur in 1947 until 1949, he was attached to command the Peshawar Air Force base in 1949–50.[19] In 1948–49, Wg-Cdr. Khan greeted Governor-General Muhammad Ali Jinnah when Jinnah visited the PAF Academy.[20] For a short brief of time in 1953, Group Captain (Gp-Capt.) Asghar was taken in deputation in the services of the Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) where he served in the corporate administration.:38[21] In 1955, Gp-Capt. Khan was appointed as the commander of the No. 1 Group.:120[22]:97[23]

In 1955–56, Air Commodore (Air-Cdre.) Khan was posted to the PAF Air Headquarters and briefly met with the Brigadier-General Saxton of the U.S. Air Force to discuss the Military Advisory Assistance Group and equipment procurement for the Pakistan Air Force.:97[23] In 1957, Air Vice-Marshal (AVM) Khan was appointed as the Deputy Commander-in-Chief of Administration and took an initiative in establishing the Air Force Education Command that oversaw the establishment of the PAF Air War College in Islamabad and the College of Aeronautical Engineering in Risalpur.[19]

Commander-in-Chief and President of Pakistan International Airlines

In 1957, the Government of Pakistan announced the retirement of the Royal Air Force's Air Vice-Marshal (AVM) Sir Arthur McDonald, and promoted AVM Asghar Khan to the two-star rank.:v[10] In 1957, AVM Khan took over the command of the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) as its first, and the youngest, Air Commander in the military– he was only aged 36 at the time of his promotion.[25] In 1958, AVM Khan's rank was upgraded to three-star rank .:v[10][25]

Soon after his promotion in 1958, as Air Marshal (Air-Mshl) Khan soon become involved in national politics and harboured strong feelings towards the nation's politicians involved in monetary corruption.:104[26] He sided with Army Commander, General Ayub Khan against the Navy Commander, Vice-Admiral H. M. S. Choudhri over the contingency plans and management of the Joint Staff.:381–382[27] Eventually, Lt-Gen. Khan played a crucial role in support of the 1958 Pakistani coup d'état, and consolidating control in support of General Ayub Khan, alongside with Admiral A. R. Khan and the 'Gang of Four', four Army and Air Force generals, Azam Khan, Amir Kan, Wajid Burkk, who were instrumental in Ayub Khan's rise to the Presidency.[26]

The overthrow of President Iskander Mirza was welcomed in public circles, Air-Mshl. Khan backed the martial law enforcement which he viewed as a necessary step to eradicate the corrupt practices found in the nation's politics.:104[26][28] In 1960, Air-Mshl. Khan was given an extension and was allowed to continue commanding the Air Force.:37[29] In 1963, his second extension by approved by President Ayub Khan, which was set till 1965.[24] During this time, Air-Mshl. Khan maintained close ties with the U.S. Air Force to continue training and supported the test pilot program where many Pakistan Air Force pilots qualified as career test pilots on U.S. military aircraft.[23]

In 1965, Air-Mshl. Khan reportedly was in conflict with the army department led by its army commander General Musa Khan when he questioned the contingency plans and secret infiltration into the Indian held side of Kashmir.[30] Air-Mshl. Khan reported that neither the Air Force nor the Pakistan Navy was kept informed by military planners when the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965 (the second war with India) broke out.[31] Before the declaration of war by either side, Air-Mshl. Khan reportedly spoke with Air-Mshl. Arjan Singh, the Indian Air Force's Chief of the Air Staff, where both reached a mutual understanding for avoiding bombardment of each sides residential cities.:17[32]

Khan boldly came out against the war with India during a meeting with President Ayub Khan and correctly calculated that "a provoked India is likely to respond along the border in an all-out war."[24] Though, President Ayub took the war option after being convinced by the arguments presented by his Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.[24]

In August 1965, President Ayub Khan reportedly refused to approve Air-Mshl. Asghar Khan's extension papers for a third term and Khan was replaced in his command when Air Vice Marshal Nur Khan was appointed to the post.:67[29]:148[33] By the time Air-Mshl. Asghar was replaced from his command appointment, the Pakistan Air Force had been a formidable branch of the armed forces.[31]

After leaving command of the Air Force, President Ayub Khan appointed Ashgar Khan as the President of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) which he served with his rank.[34][35][36] There, Khan qualified to fly commercial aircraft and obtained his commercial pilot license.[36] Khan transformed the corporate culture into professionalism when he introduced new uniforms for the air hostesses and stewards, which earned admiration at domestic and international airports.[37]

After the deadly Pakistan International Airlines Flight 17 incident took place in 1966 involving the PIA East Pakistan Helicopter Service, Khan stressed aviation safety, which led to PIA achieving the lowest aircraft accident rate, and highest net profit of Pakistan, and was a formidable competitor in the world airline business.[38] In addition, Asghar Khan briefly served as the Director-General of the Pakistani Civil Aviation Authority (CAA) from 1965 until retiring in 1968.:196[39] His tenure as PIA President is often remembered as the "Golden Age of PIA" by his supporters.[38] In 1968, Khan retired from military service and also left the corporate affairs of the airline.[2]

Political career in Pakistan

Solidarity Party, politics of agitation and support for martial law

After retiring from his military service, Asghar Khan announced he was forming a political party, the Tehrik-e-Istiqlal (TeI) (lit. Movement for Solidarity Party), in response to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's announcement of the formation of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP).[24] The TeI was a centrist political party founded in direct opposition to the left-wing PPP, though both were opposing the Ayub administration.:169[40] Despite its centerist and secular program, the TeI attracted the right-wing conservative vote bank and support from the Muttahida Majlis-e-Amals ultraconservative clergy.:169[40][41] During the election campaign in 1969–70, Khan placed the blame on Zulfikar Ali Bhutto for starting the second war with India in 1965 after reading a statement from Ayub Khan after meeting the latter.:23–24[42]

He also was very critical of Bhutto and Mujibur Rahman (Mujib) when they quietly sustained the overturn of the Government of Pakistan under President Yahya Khan.:89–90[43] He was later imprisoned alongside Bhutto and Mujib for sometime, sharing the limelight in the news for his imprisonment.:76[44] In protest in 1969, Khan renounced the civil awards bestowed to him by the Government of Pakistan.:vii[45] He later advised President Yahya Khan on transferring the control of the government to Mujibur Rahman to prevent the breaking-up the unity of Pakistan as early as 1971.:contents[46]

During the nationwide 1970 Pakistani general elections, Khan decided to run on the Rawalpindi's constituencies, believing that the city's population would vote in appreciation of a retired air force general who is also close to the military establishment.:76[44] However, Khan clearly lost the election to the less-known politician, Khurshid Hasan Mir of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP); the Tehrik-e-Istiqlal (TeI) generally lost the election without winning any seats for the National Assembly of Pakistan as the PPP had performed well to claim the exclusive mandate in the Four Provinces of Pakistan.:159[47]

After the disastrous Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, the third war with India, Khan joined the National Assembly, only to be served in the Opposition bench led by Wali Khan of the communist Awami National Party.:159[47][36] After Yahya administration turned over the civilian government to Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as President, Khan accused Bhutto of escalating the situation that led to the Breakup of East and West Pakistan and noting that: "We are living virtually under one-party state... The outstanding feature is suppression."[41]

In 1973, his criticism of Prime Minister Bhutto grew further and Khan held him directly responsible for authorizing the 1970s military operations to curb nationalism in Balochistan, Pakistan.:205[48][41] In 1974, Khan criticized the nationalization of industry in Pakistan and his party benefitted from financial support from industrialists such as Nawaz Sharif, Javed Hashmi, Shuja'at Hussain to oppose such policy measures.[4] In 1975–76, Khan eventually supported and was instrumental in forming the National Front, a massive nine-party conservative alliance, and was said to be determined to oust Bhutto and his party from the government and power.:163[49]

Khan participated in the 1977 Pakistani general election on his previous constituency but lost the elections to less-known politicians, much to his surprise.:76[44] He refused the election results and leveled charges on the government of vote rigging, immediately calling for the massive dharnas against the government.:76[44] When provincial governments led the arrests of workers from the National Front, it was reported by historians that it was Khan who penned a letter to the Chairman Joint Chiefs Admiral Mohammad Shariff and Army Chief General Zia-ul-Haq reminding them of not to obey the law of their civilian superiors.:68[50]:contents[51] Excerpts of this letter was later published by the historians as Khan later asking the military to renounce their support for the "Illegal regime of Bhutto", and asked the military leadership to "differentiate between a "lawful and an unlawful" command... and save Pakistan.".:181[52]

To the historians and observer, the letter was a pivot for the military to engage in establishing martial law against Prime Minister Bhutto in 1977.:68[50][52] Khan was reportedly offered a cabinet post in the Zia administration but he declined to serve.[52]

Imprisonment and political struggle to maintain image

After the imposing of martial law by the bloodless 5 July 1977 Operation Fair Play coup by the Army Chief, General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq, Khan began opposing the Zia administration and called for support for restoring democracy.[52] On television interviews with news channels, Khan strongly defended his letter as according to him, "nowhere in the letter had he asked for the military to take over", and he had written it in response to a news story he read in which an Army Major had shot a civilian showing him the "V sign".[52]

In 1983, Khan went on to join the left-wing alliance, the Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) led by Benazir Bhutto, supported by the communist parties at that time.[53]

Khan was kept under house arrest at his Abbottabad residence from 16 October 1979 to 2 October 1984 and was named a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International.[54] In 1986, Khan left the MRD, which was under the influence of the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and Awami National Party (ANP), and had paving a way for the Bhuttoism which had irked Khan.:51–52[55] His decision of boycotting the non-partisan 1985 Pakistani general election eventually led to many of his party's key member defecting to the Pakistan Muslim League led by its President M. K. Junejo.:134[56]

In 1988, his letter calling for support for martial law became a public matter Khan and failed to defend his multiple constituencies against the PPP's politicians when the 1988 Pakistani general elections were held.:114–115[57] He also lost the 1988 general elections and leveled accusations on the military of financing (Mehrangate) the conservative Pakistan Muslim League (N) (PML(N)) and PPP.:187[58] He eventually took his case to the Supreme Court of Pakistan where the hearings of his case are still being heard by the Nisar Court of present.[5] In 1997, Khan boycotted the 1997 Pakistani general elections.:703[59]

Public disapproval and merging with Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf

Since 1990, Khan's political image had failed to sustain any political influence in Pakistan.[60] In 1998–99, Asghar Khan made unsuccessful attempts to merge his party's cause to Imran Khan's PTI.:887[61]

In 2002, he handed over his small party to his elder son, Omar Asghar Khan, who was a cabinet minister in the early Musharraf administration.[60] After his son's death in 2002, Khan joined the National Democratic Party in 2004, which he remained part of until 2011.:428[62] On 12 December 2011, Ashgar Khan announced his full support of the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) and Imran Khan.[63] He praised Imran Khan for his struggle and endorsed him as the only hope left for the survival of Pakistan.[63] This endorsement came at a crucial time for Imran Khan, when many tainted politicians were joining his party.[63][64]

Dissent: Criticism on state, military and politicians

During this political career, Khan was very critical of the Pakistan Army's involvement in politics and issued a strong criticism to the Pakistan Army's general, in the first instance in 1980, which led to his imprisonment– he stressed the importance of civilian control of the military for economic development.:133[65] On various occasion, Khan called for normalisation of Indo-Pakistani relations and reportedly accused the Pakistan Army of inciting deliberate attempts to start the conflict with India.[66] Khan also renounced the nuclear test operations conducted by Pakistan, targeting Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif for making that decision[66] In 2011 Khan maintained that:

In the last over 60 years, India has never attacked Pakistan, as it cannot afford it. Indians know well, if Pakistan is destroyed, they will be the next target... It was made our problem that one day India would invade us. But we did so four times and the first attack was on Kashmir, where Maharaja was not prepared to accede to India for he wanted to join Pakistan and waited for this for 21 days. Indian forces came to East-Pakistan when people were being slaughtered there. Moreover, again at Kargil, Indian never mounted an assault...

— Asghar Khan, 2011, [66]

In 1972, Khan accused Zulfikar Ali Bhutto for the East Pakistan-West Pakistan War 1971 causing the break-up of the country, later blatantly blaming Bhutto for starting the Balochistan conflict in Western Pakistan in 1976, and the Bangladesh Liberation War in Eastern Pakistan in 1971, terming it "inflexible attitude" of Bhutto.[66][67]

Commenting on his political collapse, Khan accused Pakistani society for his failure, and marked that: "the majority in Pakistan voted for the (corrupt) politicians, as they also wanted their job done by "hook or by crook".[66]

In the 1990s, he briefly fought several legal battles against his country's elected politicians where he accused them of involved in monetary corrupt practices, and eventually filed a lawsuit against the Pakistan Peoples Party and Pakistan Muslim League (N) in the Supreme Court of Pakistan.[66] He held numerous televised press conferences where he attached the case file of his lawsuits and penned an article to the public: Is Hamam Main Sab Nangay… (lit. Everyone's naked in this bathroom...).[68]

Khan was a prolific political writer and historian where he penned criticism on the politics of Pakistans' Army and the role of the military establishment in a country's political system. Of 13 books, three of his popular bibliography included: We've Learnt Nothing from History, Pakistan at the Crossroads and Generals in Politics.[19]

Personal life, death and funeral

Asghar Khan was married to Amina Shamsie (Amina Asghar Khan) in 1946 and they had four children, Nasreen, Sheereen, Omar (deceased) and Ali Asghar Khan.:103[69] Asghar Khan died on 5 January 2018, two weeks shy of his 97th birthday.[70][3] The government of Pakistan buried him with full state honours and he was given a state funeral.[71]

Selected books

English

- Khan, Ashghar (1969). Pakistan at the Cross Roads. Karachi: Ferozsons. OCLC 116825.

- —— (1979). The First Round, Indo-Pakistan War 1965. Sahibabad: Vikas. ISBN 0-7069-0978-X.

- —— (1983). Generals in Politics. New Delhi: Vikas. ISBN 0-7069-2215-8.

- —— (1985). The Lighter side of the Power Game. Lahore: Jang Publishers. OCLC 15107608.

- —— (2005). We've Learnt Nothing from History. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-597883-8.

- —— (2008). My Political Struggle. Karachi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-547620-0.

- —— (2009). Milestones in a Political Journey. Islamabad: Dost Publications. ISBN 978-9694963556.

Urdu

- Khan, Ashghar (1985). Sada-i-Hosh (in Urdu). Lahore: Jang Publishers. OCLC 14214332.

- —— (1998). Chehray nahi Nizam ko Badlo (in Urdu). Islamabad: Dost Publications. ISBN 978-9694960401.

- —— (1999). Islam – Jamhooriat aur Pakistan (in Urdu). Islamabad: Dost Publications. ISBN 978-9694960852.

- —— (1999). Ye Batain Hakim Logon Ki (in Urdu). Islamabad: Dost Publications. ISBN 978-9694960876.

See also

- Aman ki Asha

- Anti-Pakistan sentiment

- Hindi in Pakistan

- Indo-Pakistani Confederation Proposals

References

- Khan, Mohammad Asghar (1969). Pakistan at the cross-roads. Ferozsons. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Naseeruddin., G. (1968). Trade and Industry.

- Naveed Siddiqui, Dawn.com (5 January 2018). "Air Marshal Asghar Khan passes away in Islamabad". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- Staff report. "Air Marshal Muhammad Asghar Khan". Pakistan Herald, 14 March 2012. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Abbas, Mazhar (15 May 2018). "A story behind Asghar Khan case?". Mazhar Abbas report on GEO TV. GEO News. GEO TV. Retrieved 19 May 2018.

- "Asghar Khan: India An Imagined Enemy". 28 November 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Air Marshal Asghar Khan Exposes Pakistan Army From 1947 to 1999". 5 September 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Imran greets Asghar as Tehrik-e-Istaqlal, PTI merge". Dunyanews.tv. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "State funeral prayer for Air Marshal Asghar Khan offered in Rawalpindi - BOL News". 5 January 2018.

- Khan, Mohammad Asghar (1969). Pakistan at the Cross Roads. Lahore, Pakistan: Ferozsons.

- Bhattacharya, Brigadier Samir (2013), Nothing But!: Book Three: What Price Freedom, Partridge Publishing, p. 260, ISBN 978-1-4828-1625-9

- Wasim Khalid, Kashmiri man who laid foundation of modern Pak air Force dies at 96, Kashmir Reader, 6 January 2018.

- Muqeet Malik, The Legend of Baltistan: Brigadier Muhammad Aslam Khan, The Nation, 21 August 2015.

- Singh, Bikram; Mishra, Sidharth (1997). "§Air Marshal Asghar Khan" (google books). Where Gallantry is Tradition: Saga of Rashtriya Indian Military College : Plantinum Jubilee Volume, 1997. New Delhi, India: Allied Publishers. p. 125. ISBN 9788170236498.

- Webdesk, staff (6 January 2018). "Air Marshal Asghar Khan laid to rest". thenews.com.pk. News International, 2018. News International. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Aero News. Kitab. 1965.

- London Calling. British Broadcasting Corporation. 1945.

- "Mohammad Asghar Khan". prideofpakistan.com. Pride of Pakistan. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Kazi (MMBS). "The Founder visiting PAF Base Risalpur with Wing Commander Asghar Khan, 1948". Flicker photo, 1948. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Aeroplane Directory of British Aviation. English Universities. 1953.

- Shuja., Nawaz (2008). Crossed swords : Pakistan, its army, and the wars within. Oxford University Press. p. 655. ISBN 9780195476606.

- Hussain, Syed Shabbir; Qureshi, M. Tariq (1982). History of the Pakistan Air Force, 1947-1982 (1st ed.). Islamabad: ISPR, Pakistan Air Force. p. 332.

- Taqi, Mohammad (10 January 2018). "Asghar Khan: From Air Marshal to Dogged Opponent of Military Rule in Pakistan - The Wire". The Wire. Islamabad: Taqi at The Wire. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

He firmly believed Pakistan does not face an offensive threat from India and has nothing to fear on its eastern front unless it keeps provoking its giant neighbour...

- Press release. "Air Marshal M Asghar Khan, HPk, HQA". PAF Falcons. PAF Falcons, Chiefs of Air Staff. Archived from the original on 14 March 2010. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Rizvi, H. (15 May 2000). Military, State and Society in Pakistan. Springer, Rizvi. ISBN 9780230599048.

- Singh, Ravi Shekhar Narain Singh (2008). The Military Factor in Pakistan. Lancer Publishers, Singh. ISBN 9780981537894.

- SoP (1 June 2003). "Ouster of President Iskander Mirza". Story of Pakistan, Mirza's ouster section. Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- Akhtar, Jamna Das (1969). Political conspiracies in Pakistan: Liaquat Ali's murder to Ayub Khan's exit (1st ed.). Lahore, Punjab,Pakistan: Punjabi Pustak Bhandar. p. 380.

- Chaudhry, Shehza (31 October 2012). "The military-military divide". The Express Tribune. Islamabad: Express Tribune. Express Tribune. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- "Nur Khan reminisces '65 war". DAWN.COM. Dawn Newspapers. 6 September 2005. Retrieved 17 May 2018.

- Ganguly, Sumit (2016). Deadly Impasse: Indo-Pakistani Relations at the Dawn of a New Century (1st ed.). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-316-69236-3.

- Sahni, Naresh Chander (1969). Political Struggle in Pakistan (1st ed.). Karachi, Pakistan: New Academic Publishing Company. p. 239.

- PIA History. "PIA's Finest Men and Women". PIA History. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- PIA History. "The Legengs". PIA History.

- Khan, M. Asghar (23 August 2010). "My political struggle". The News International. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- PIA. "Photo Gallery of PIA's Finest Men and Women". The PIA Historical Department. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Masood Hasan (23 October 2011). "The promise". The News International, Sunday, 23 October 2011. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- The Commonwealth Office Year Book. H.M. Stationery Office. 1968.

- Chari, P. R.; Cheema, Pervaiz Iqbal; Cohen, Stephen P. (2009). Four Crises and a Peace Process: American Engagement in South Asia. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 978-0815713869.

- Saeed Shafqat, PhD (1997). Civil-military relations in Pakistan. Peshawar, Pakistan: Boulder: West View Press. pp. 283 pages. ISBN 978-0813388090.

- "Indian and Foreign Review". Indian and Foreign Review. Publications Division of the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. 17 (8–24). 1980.

- Kapur, Ashok (2006). Pakistan in Crisis. Routledge. ISBN 9781134989775.

- Burki, Shahid Javed (2015). Historical Dictionary of Pakistan. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442241480.

- Khan, Mohammad Asghar (1969). Pakistan at the cross-roads. Ferozsons.

- Sengupta, Nitish (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin UK. ISBN 9788184755305.

- Lyon, Peter (2008). Conflict Between India and Pakistan: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077122.

- Pakistan), Sayad Hashmi Reference Library (Karachi (2008). The Balochistan chronicles: the archives of the Times, London and the New York Times on Balochistan, from 1842-2007. Sayad Hashmi Reference Library.

- Rizvi, H. (2000). Military, State and Society in Pakistan. Springer. ISBN 9780230599048.

- Singh, Ravi Shekhar Narain Singh (2008). The Military Factor in Pakistan. Lancer Publishers. ISBN 9780981537894.

- Kapur, Ashok (2006). Pakistan in Crisis. Routledge. ISBN 9781134989768.

- Talbot, Ian (1998). Pakistan A Modern History. United States.: St. Martin's Press. pp. 181–200. ISBN 0-312-21606-8.

- Hyman, Anthony; Ghayur, Muhammed; Kaushik, Naresh (1989). Pakistan, Zia and After--. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 52. ISBN 81-7017-253-5.

The Tehrik-i-Istiqlal of retired air marshal Asghar Khan had also joined the MRD by [1984] ... The so-called 'three Khans' – Nazrullah Khan of the Pakistan Democratic Party, Walid Khan of National Awami Party and Asghar Khan of the Tehrik – opposed [participation in the 1985 elections] and carried the rest with them.

- "Pakistan". Amnesty International. 1981. Retrieved 22 January 2012.

- Pakistan Review. S. Ahmad. 1985.

- Hyman, Anthony; Ghayur, Muhammed; Kaushik, Naresh (1989). Pakistan, Zia and After--. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. p. 134. ISBN 81-7017-253-5.

Once the [1988] National Assembly elections were over ... Air Marshal Asghar Khan, leader of the Tehrik-i-Istiklal party, has been swept aside, in both the constituencies where he contested the elections from.

- Electoral Politics in Pakistan: National Assembly Elections 1993 : Report of Saarc-Ngo Observers. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. 1995. ISBN 9780706987317.

- Tushnet, Mark; Khosla, Madhav (2015). Unstable Constitutionalism: Law and Politics in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. p. 400. ISBN 9781316419083.

- Banks, Arthur S.; Day, Alan J.; Muller, Thomas C. (2016). Political Handbook of the World 1998. Springer. ISBN 9781349149513.

- Zia Khan (13 December 2011). "Reinforcement: Asghar Khan is latest PTI recruit". The Express Tribune. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Banks, William C.; Muller, T.; Overstreet, W. (2005). Political Handbook of theWorld 2005-2006. CQ Press. ISBN 9781568029528.

- South Asia 2004. Taylor & Francis. 2003.

- Press Release (12 December 2011). "Asghar Khan backs Imran's PTI". Dawn Newspapers, 2011. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Press Release (12 December 2011). "Air Marshal (retd) Asghar Khan to join PTI". Pakistan Tribune. Retrieved 14 March 2012.

- Degenhardt, Henry W.; Day, Alan John (1983). Political dissent: an international guide to dissident, extra-parliamentary, guerrilla, and illegal political movements. Gale Research Company. ISBN 9780582902558. Retrieved 20 May 2018.

asghar khan national democratic party.

- Alvi, Mumtaz (21 October 2011). "Asghar Khan claims Pakistan attacked India four times since 1947". The News International, October 2011. Archived from the original on 31 March 2012. Retrieved 15 March 2012.

- Inam R Sehri (2015). The Living History of Pakistan Vol-I. GHP Surrey UK. pp. 1651–76.

- Inam R Sehri (2012). Judges & Generals in Pakistan Vol-I. GHP Surrey UK. pp. 168–73.

- Vikrant. 1973.

- "First Muslim air chief of PAF Asghar Khan dies". En.dailypakistan.com.pk. Retrieved 5 January 2018.

- "State funeral for former air chief Asghar Khan held at Nur Khan Airbase - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 6 January 2018. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

External links

- Bio of Air Marshal Asghar Khan

- Biography of Asghar Khan

- "State funeral prayer for Air Marshal Asghar Khan offered in Rawalpindi - BOL News". 5 January 2018.

- "Asghar Khan: India An Imagined Enemy". 28 November 2009. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

- "Air Marshal Asghar Khan Exposes Pakistan Army From 1947 to 1999". 5 September 2015. Retrieved 21 May 2018.

| Military offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Arthur McDonald |

Commander-in-Chief, Pakistan Air Force 1957–1965 |

Succeeded by Nur Khan |