Economy of Colombia

The economy of Colombia is the fourth largest in Latin America as measured by gross domestic product.[19] Colombia has experienced a historic economic boom over the last decade. In 1990, Colombia was Latin America's 5th largest economy and had a GDP per capita of only US$1,500, by 2018 it became the 4th largest in Latin America, and the world's 37th largest. As of 2018 the GDP (PPP) per capita has increased to over US$14,000, and GDP (PPP) increased from US$120 billion in 1990 to nearly US$750 billion.[4] Poverty levels were as high as 65% in 1990, but decreased to under 30% by 2014.[8]

Downtown Bogotá | |

| Currency | Colombian peso (COP) |

|---|---|

| Calendar year | |

Trade organizations | WTO, OECD, Pacific Alliance, CAN, ALADI, Prosur, Mercosur (associate), Unasur (suspended) |

Country group |

|

| Statistics | |

| Population | |

| GDP | |

| GDP rank | |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | |

GDP per capita rank | |

GDP by sector |

|

| 3.5% (2020 est.)[5] | |

Population below poverty line | |

Labor force | |

Labor force by occupation |

|

| Unemployment | |

Main industries | textiles, food processing, oil, clothing and footwear, beverages, chemicals, cement; gold, coal, emeralds, shipbuilding, electronics industry, home appliance |

| External | |

| Exports | |

Export goods | petroleum, coal, coffee, gold, bananas, cut flowers, coke (fuel), ferroalloys, emeralds |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | |

Import goods | industrial equipment, transportation equipment, electric machinery and equipment, organic chemicals, pharmaceutical products, medical and optical equipment |

Main import partners | |

FDI stock | |

Gross external debt | |

| Public finances | |

| −2.7% (of GDP) (2017 est.)[7] | |

| Revenues | 83.35 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

| Expenses | 91.73 billion (2017 est.)[7] |

| Economic aid | $32 billion |

| |

Foreign reserves | |

Petroleum is Colombia's main export, making over 45% of Colombia's exports. Manufacturing makes up nearly 12% of Colombia's exports, and grows at a rate of over 10% a year. Colombia has the fastest growing information technology industry in the world and has the longest fibre optic network in Latin America.[20] Colombia also has one of the largest shipbuilding industries in the world outside Asia.

Modern industries like shipbuilding, electronics, automobile, tourism, construction, and mining, grew dramatically during the 2000s and 2010s, however, most of Colombia's exports are still commodity-based. Colombia is Latin America's 2nd-largest producer of domestically-made electronics and appliances only behind Mexico. Colombia had the fastest growing major economy in the western world in 2014, behind only China worldwide.[21][22]

Since the early 2010s, the Colombian government has shown interest in exporting modern Colombian pop culture to the world (which includes video games, music, movies, TV shows, fashion, cosmetics, and food) as a way of diversifying the economy and entirely changing the image of Colombia; a national campaign similar to the Korean Wave.[23] In the Hispanic world, Colombia is only behind Mexico in cultural exports and is already a regional leader in cosmetic and beauty exports.[24]

The number of tourists in Colombia grows by over 12% every year. Colombia is projected to have over 15 million tourists by 2023.[25][26]

History

16th–19th centuries

European explorers reached what is now Colombian territory as early as 1510 in Santa María Antigua del Darién (in present-day Chocó department). For the next couple of decades Colombia, and South America in general, remained largely unexplored. From 1533 to 1600, Europeans began expeditions into the interior of current Colombia. The intent of these expeditions was mainly to conquer new lands and exploit village resources. Legends of El Dorado that reached Spaniard explorers continued to fuel exploration and raiding of Indian villages.

In the 17th century, Spanish conquerors explored Colombia and made the first settlements, and this was the beginning of Colombia's modern economic history. Major conquistadors from this period were Pedro de Heredia, Gonzalo Jimenez de Quesada, Sebastián de Belalcazar, and Nikolaus Federmann.

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the colonial settlements in Colombia served purposes of extraction of precious metals and other natural resources, and later slavery trade. This economic arrangement left the Colony with little room for building solid institutionality for economic development. The main non-extractive institutions emerging in this centuries were the fortified port of Cartagena and the Viceroyalty of New Granada. Cartagena developed military defenses mainly out of necessity from frequently having to deal with pirate attacks. A primitive form of colonial administration was organized in Santa fé de Bogotá with the Viceroyalty of New Granada, especially under the tenure of José Solís y Folch de Cardona (1753–1761), who conducted a census and built roads, bridges and aqueducts.

Following the War of the Thousand Days (1899–1902), Colombia experienced a coffee boom that catapulted the country into the modern period, bringing the attendant benefits of transportation, particularly railroads, communications infrastructure, and the first major attempts at manufacturing.

20th century

Colombia's consistently sound economic policies and aggressive promotion of free trade agreements in recent years have bolstered its ability to weather external shocks. Real GDP has grown more than 4% per year for the past three years, continuing almost a decade of strong economic performance.[7]

In 1990, the administration of President César Gaviria Trujillo (1990–94) initiated economic liberalism policies or "apertura economica" and this has continued since then, with tariff reductions, financial deregulation, privatization of state-owned enterprises, and adoption of a more liberal foreign exchange rate. Almost all sectors became open to foreign investment although agricultural products remained protected.

The original idea of his then Minister of Finance, Rudolf Homes, was that the country should import agricultural products in which it was not competitive, like maize, wheat, cotton and soybeans and export the ones in which it had an advantage, like fruits and flowers. In ten years, the sector lost 7,000 km2 to imports, represented mostly in heavily subsidized agricultural products from the United States, as a result of this policy, with a critical impact on employment in rural areas.[27] Still, this policy makes food cheaper for the average Colombian than it would be if agricultural trade were more restricted.

Until 1997, Colombia had enjoyed a fairly stable economy. The first five years of liberalization were characterized by high economic growth rates of between 4% and 5%. The Ernesto Samper administration (1994–98) emphasized social welfare policies which targeted Colombia's lower income population. These reforms led to higher government spending which increased the fiscal deficit and public sector debt, the financing of which required higher interest rates. An over-valued peso inherited from the previous administration was maintained.

The economy slowed, and by 1998 GDP growth was only 0.6%. In 1999, the country fell into its first recession since the Great Depression. The economy shrank by 4.5% with unemployment at over 20%. While unemployment remained at 20% in 2000, GDP growth recovered to 3.1%.

The administration of President Andrés Pastrana Arango, when it took office on 7 August 1998, faced an economy in crisis, with the difficult internal security situation and global economic turbulence additionally inhibiting confidence. As evidence of a serious recession became clear in 1999, the government took a number of steps. It engaged in a series of controlled devaluations of the peso, followed by a decision to let it float. Colombia also entered into an agreement with the International Monetary Fund which provided a $2.7 billion guarantee (extended funds facility), while committing the government to budget discipline and structural reforms.

By early 2000 there had been the beginning of an economic recovery, with the export sector leading the way, as it enjoyed the benefit of the more competitive exchange rate, as well as strong prices for petroleum, Colombia's leading export product. Prices of coffee, the other principal export product, have been more variable.

Economic growth reached 3.1% during 2000 and inflation 9.0%. Colombia's international reserves have remained stable at around $8.35 billion, and Colombia has successfully remained in international capital markets. Colombia's total foreign debt at the end of 1999 was $34.5 billion with $14.7 billion in private sector and $19.8 billion in public sector debt. Major international credit rating organizations have dropped Colombian sovereign debt below investment grade, primarily as a result of large fiscal deficits, which current policies are seeking to close.

Former president Álvaro Uribe (elected 7 August 2002) introduced several neoliberal economic reforms, including measures designed to reduce the public-sector deficit below 2.5% of GDP in 2004. The government's economic policy and controversial democratic security strategy have engendered a growing sense of confidence in the economy, particularly within the business sector, and GDP growth in 2003 was among the highest in Latin America, at over 4%. This growth rate was maintained over the next decade, averaging 4.8% from 2004 to 2014.[28]

Overview

The longstanding internal armed conflict in Colombia has had economic impacts.

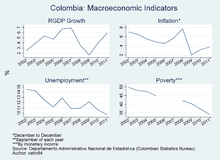

In the early 21st century, the Colombian economy grew in part because of austere government budgets, focused efforts to reduce public debt levels, an export-oriented growth strategy, an improved security situation in the country, and high commodity prices. Growth slowed to 1.4 percent in 2017, and then increased to 3.3 percent in 2019.[29]

President Uribe, who was in office from 2002–2010, examined opportunities including reforming the pension system, reducing high unemployment, achieving congressional passage of a fiscal transfers reform, and exploring for new oil or producing ethanol. Colombia's Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, was one of the highest in South America.[30] International and domestic financial analysts warned of the growing central government deficit, which hovered at 5% of GDP. Nonetheless, confidence in the economy grew.

Household income or consumption by percentage share: lowest 10%: 0.8% highest 10%: 45.9% (2006)

Investment (gross fixed): 24.3% of GDP (2008 est.)

Budget: revenues: $83.22 billion expenditures: $82.92 billion; including capital expenditures of $NA (2008 est.)

Central bank discount rate: 11.5% (31 December 2008)

Commercial bank prime lending rate: 15.6% (31 December 2008)

Stock of money: $21.58 billion (31 December 2008)

Stock of quasi money: $26.57 billion (31 December 2008)

Stock of domestic credit: $89.69 billion (31 December 2008)

Market value of publicly traded shares: $87.03 billion (31 December 2008)

Agriculture – products: coffee, cut flowers, bananas, rice, tobacco, corn, sugarcane, cocoa beans, oilseed, vegetables; forest products; shrimp

Industries: textiles, food processing, oil, clothing and footwear, beverages, chemicals, cement; gold, coal, emeralds, shipbuilding, electronics, home appliance, and furniture.

Industrial production growth rate: 2% (2013 est.)

Electricity – production: 53.6 billion kWh (2007)

Electricity – consumption: 52.8 billion kWh (2007)

Electricity – exports: 876.7 million kWh (2007)

Electricity – imports: 38.4 million kWh (2007)

Oil – production: 588,000 bbl/d (93,500 m3/d) (2008 est.)

Oil – consumption: 267,000 bbl/d (42,400 m3/d) (2007 est.)

Oil – exports: 294,000 bbl/d (46,700 m3/d) (2008 est.)

Oil – imports: 12,480 bbl/d (1,984 m3/d) (2005)

Oil – proved reserves: 1,323,000,000 bbl (210,300,000 m3) (1 January 2008 est.)

Natural gas – production: 7.22 billion cu m (2006 est.)

Natural gas – consumption: 7.22 billion cu m (2006 est.)

Natural gas – exports: 0 cu m (2007 est.)

Natural gas – imports: 0 cu m (2007 est.)

Natural gas – proved reserves: 122.9 billion cu m (1 January 2008 est.)

Current account balance: $−6.761 billion (2008 est.)

Exchange rates: Colombian pesos (COP) per US dollar – 2,243.6 (2008), 2,013.8 (2007), 2,358.6 (2006), 2,320.75 (2005), 2,628.61 (2004)

Source:[7]

Development of main indicators

The following table shows the main economic indicators in 1980–2017. Inflation under 5% is in green.[31]

| Year | GDP (in Bil. US$ PPP) |

GDP per capita (in US$ PPP) |

GDP growth (real) |

Inflation rate (in percent) |

Unemployment (in percent) |

Government debt (in % of GDP) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1980 | 78.9 | 2,772 | 5.4% | n/a | ||

| 1981 | n/a | |||||

| 1982 | n/a | |||||

| 1983 | n/a | |||||

| 1984 | n/a | |||||

| 1985 | n/a | |||||

| 1986 | n/a | |||||

| 1987 | n/a | |||||

| 1988 | n/a | |||||

| 1989 | n/a | |||||

| 1990 | n/a | |||||

| 1991 | n/a | |||||

| 1992 | n/a | |||||

| 1993 | n/a | |||||

| 1994 | n/a | |||||

| 1995 | n/a | |||||

| 1996 | 23.1% | |||||

| 1997 | ||||||

| 1998 | ||||||

| 1999 | ||||||

| 2000 | ||||||

| 2001 | ||||||

| 2002 | ||||||

| 2003 | ||||||

| 2004 | ||||||

| 2005 | ||||||

| 2006 | ||||||

| 2007 | ||||||

| 2008 | ||||||

| 2009 | ||||||

| 2010 | ||||||

| 2011 | ||||||

| 2012 | ||||||

| 2013 | ||||||

| 2014 | ||||||

| 2015 | ||||||

| 2016 | ||||||

| 2017 |

Graphics

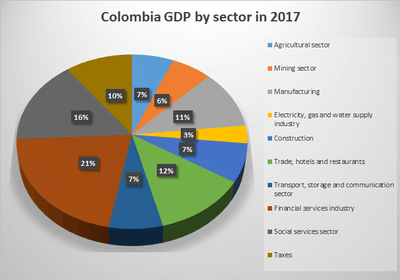

Colombia GDP by sector in 2017[32]

Labor rights

On 8 June 2020, the newly formed Employment Mission (Misión de Empleo) met for the first time to discuss labor reforms that it intended to propose to Congress. Some of these reforms had been desired for years, and others had come into starker view during the coronavirus pandemic.[34]

Industry and agriculture

Manufacturing

Domestic appliances

Although Colombia has been producing domestic appliances since the 1930s, it wasn't until the late 1990s that Colombian corporations began exporting to neighboring countries. One of Colombia's largest producers of domestic appliances, HACEB has been producing refrigeration since 1940. Some domestic corporations include: Challenger, Kalley, HACEB, Imusa, and Landers. In 2011, Groupe SEB acquired Imusa as a form to expand to the Latin American market.[35] Colombia also manufactures for foreign companies as well, such as Whirlpool and GE.[36] LG has also been interested in building a plant in Colombia. Colombia is also Latin America's 3rd largest producer of appliances behind Mexico and Brazil and is growing rapidly.

Electronics

Colombia is a major producer of electronics in Latin America, and is South America's 2nd largest high-tech market.[37] Colombia is also the 2nd largest producer and exporter of electronics made by domestic companies in Latin America. Since the early 2000s, major Colombian corporations began exporting aggressively to foreign markets. Some of these companies include: Challenger, PcSmart, Compumax, Colcircuirtos, and Kalley. Colombia is the first country in Latin America to manufacture a domestically made 4K television.[38] In 2014, the Colombian Government launched a national campaign to promote IT and Electronic sectors, as well as investing in Colombia's own companies.[37] Although innovation remains low on the global scale, the government sees heavy potential in the high tech industry and is investing heavily in education and innovation centers all across the nation. Because of this, Colombia could become a major global manufacturer of electronics and play an important role in the global high tech industry in the near future. In 2014, the Colombian government released another national campaign to help Colombian companies have a bigger share of the national market.[39]

Construction

Construction recently has played a vital role in the economy, and is growing rapidly at almost 20% annually. As a result, Colombia is seeing a historic building boom. The Colombian government is investing heavily in transport infrastructure through a plan called "Fourth Generation Network". The target of the Colombian government is to build 7,000 km of roads for the 2016–2020 period and reduce travel times by 30% and transport costs by 20%. A toll road concession program will comprise 40 projects, and is part of a larger strategic goal to invest nearly $50bn in transport infrastructure, including: railway systems; making the Magdalena river navigable again; improving port facilities; as well as an expansion of Bogotá's airport.[40] Long-term plans include building a national high-speed train network, to vastly improve competitiveness.

Agriculture

The share of agriculture in GDP has fallen consistently since 1945, as industry and services have expanded. However, Colombia's agricultural share of GDP decreased during the 1990s by less than in many of the world's countries at a similar level of development, even though the share of coffee in GDP diminished in a dramatic way. Agriculture has nevertheless remained an important source of employment, providing a fifth of Colombia's jobs in 2006.[41]

The most industrially diverse member of the five-nation Andean Community, Colombia has four major industrial centers—Bogota, Medellin, Cali, and Barranquilla, each located in a distinct geographical region. Colombia's industries include textiles and clothing, particularly lingerie, leather products, processed foods and beverages, paper and paper products, chemicals and petrochemicals, cement, construction, iron and steel products, and metalworking. Its diverse climate and topography permit the cultivation of a wide variety of crops. In addition, all regions yield forest products, ranging from tropical hardwoods in the hot country to pine and eucalyptus in the colder areas.

Cacao beans, sugarcane, coconuts, bananas, plantains, rice, cotton, tobacco, cassava, and most of the nation's beef cattle are produced in the hot regions from sea level to 1,000 meters elevation. The temperate regions—between 1,000 and 2,000 meters—are better suited for coffee; cut flowers; maize and other vegetables; and fruits such as citrus, pears, pineapples, and tomatoes. The cooler elevations—between 2,000 and 3,000 meters—produce wheat, barley, potatoes, cold-climate vegetables, flowers, dairy cattle, and poultry.

Mining and energy

Colombia is well-endowed with minerals and energy resources. It has the largest coal reserves in Latin America, and is second to Brazil in hydroelectric potential. Estimates of petroleum reserves in 1995 were 3.1 billion barrels (490,000,000 m3). It also possesses significant amounts of nickel, gold, silver, platinum, and emeralds.

The discovery of 2 billion barrels (320,000,000 m3) of high-quality oil at the Cusiana and Cupiagua fields, about 200 kilometres (120 mi) east of Bogotá, has enabled Colombia to become a net oil exporter since 1986. The Transandino pipeline transports oil from Orito in the Department of Putumayo to the Pacific port of Tumaco in the Department of Nariño.[42] Total crude oil production averages 620 thousand barrels per day (99,000 m3/d); about 184 thousand barrels per day (29,300 m3/d) is exported. The Pastrana government has significantly liberalized its petroleum investment policies, leading to an increase in exploration activity. Refining capacity cannot satisfy domestic demand, so some refined products, especially gasoline, must be imported. Plans for the construction of a new refinery are under development.

While Colombia has vast hydroelectric potential, a prolonged drought in 1992 forced severe electricity rationing throughout the country until mid-1993. The consequences of the drought on electricity-generating capacity caused the government to commission the construction or upgrading of 10 thermoelectric power plants. Half will be coal-fired, and half will be fired by natural gas. The government also has begun awarding bids for the construction of a natural gas pipeline system that will extend from the country's extensive gas fields to its major population centers. Plans call for this project to make natural gas available to millions of Colombian households by the middle of the next decade.

As of 2004, Colombia has become a net energy exporter, exporting electricity to Ecuador and developing connections to Peru, Venezuela and Panama to export to those markets as well. The Trans-Caribbean pipeline connecting western Venezuela to Panama through Colombia is also under construction, thanks to cooperation between presidents Álvaro Uribe of Colombia, Martín Torrijos of Panama and Hugo Chávez of Venezuela. Coal is exported to Turkey.

Human rights abuses in mining zones

The oil pipelines are a frequent target of extortion and bombing campaigns by the National Liberation Army (ELN) and, more recently, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC). The bombings, which have occurred on average once every 5 days, have caused substantial environmental damage, often in fragile rainforests and jungles, as well as causing significant loss of life. In April 1999 in Cartagena de Indias, Clinton's Secretary of Energy Bill Richardson spoke before investors from the United States, Canada and other countries. He expressed his government's willingness to use military aid to support the investment that they and their allies were going to make in Colombia, especially in strategically important sectors like mining and energy.

In 2002 there were 170 attacks on the 2nd largest pipeline, which travels 780 km from the Caño Limón to the Atlantic port of Coveñas. The pipeline was out of operation for 266 days of that year; the government estimates that these bombings reduced Colombia's GDP by 0.5%. The government of the United States increased military aid, in 2003, to Colombia to assist in the effort to defend the pipeline. Occidental Petroleum privately contracted mercenaries who flew Skymaster planes, from AirScan International Inc., to patrol the Cano Limon-Covenas pipeline. Many of these operations used helicopters, equipment and weapons provided by the U.S. military and anti-narcotics aid programs.

Mining and natural exploitation has had environmental consequences. The region of Guajira is undergoing an accelerated desertification with the disappearances of forests, land, and water sources, due to the increase in coal production.[43] Social consequences or lack of development in resource rich areas is common. 11 million Colombians survive on less than one dollar a day. Over 65% of these live in mining zones. There are 3.5 million children out of school, and the most critical situation is in the mining zone of Choco, Bolivar, and Sucre.

Economic consequences of privatization and liberal institutions have meant changes in taxation to attract foreign investment. Colombia will lose another $800 million over the next 90 years that Glencore International operates in El Cerrejon Zona Media, if the company continues to produce coal at a rate of 5 million tons/year, because of the reduction of the royalty tax from 10-15% to .04%. If the company, as is plausible, doubles or triples its production, the losses will be proportionally greater. The operational losses from the three large mining projects (El Cerrejon, La Loma, operated by Drummond, and Montelíbano, which produces ferronickel) for Colombia to more than 12 billion.

Coal production has grown rapidly, from 22.7 million tons in 1994 to 50.0 million tons in 2003.[44] Over 90% of this amount was exported, making Colombia the world's sixth largest coal exporter, behind Australia, China, Indonesia, South Africa and Russia.[45] From the mid-1980s the center of coal production was the Cerrejón mines in the Guajira department. However, the growth in output at La Loma in neighboring Cesar Department made this area the leader in Colombian coal production since 2004. Production in other departments, including Boyacá, Cundinamarca and Norte de Santander, forms about 13% of the total. The coal industry is largely controlled by international mining companies, including a consortium of BHP Billiton, Anglo American and Glencore International at Cerrejón, and Conundrum Company at La Loma, which is undergoing a lawsuit in the U.S. District Court in Alabama for union assassinations and alleged paramilitary links.

Foreign investment

In 1990, to attract foreign investors and promote trade, an experiment from the International Monetary Fund[46] known as "La Apertura" was adopted by the government as an open trade strategy. Although the analysis of the results are not clear, the fact is that the agricultural sector was severely impacted by this policy.

In 1991 and 1992, the government passed laws to stimulate foreign investment in nearly all sectors of the economy. The only activities closed to foreign direct investment are defense and national security, disposal of hazardous wastes, and real estate—the last of these restrictions is intended to hinder money laundering. Colombia established a special entity—Converter—to assist foreigners in making investments in the country. Foreign investment flows for 1999 were $4.4 billion, down from $4.8 billion in 1998.

Major foreign investment projects underway include the $6 billion development of the Cusiana and Cupiagua oil fields, development of coal fields in the north of the country, and the recently concluded licensing for establishment of cellular telephone service. The United States accounted for 26.5% of the total $19.4 billion stock of non-petroleum foreign direct investment in Colombia at the end of 1998.

On 21 October 1995, under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA), President Clinton signed an Executive Order barring U.S. entities from any commercial or financial transactions with four Colombian drug kingpins and with individuals and companies associated with the traffic in narcotics, as designated by the Secretary of the Treasury in consultation with the Secretary of State and the Attorney General. The list of designated individuals and companies is amended periodically and is maintained by the Office of Foreign Asset Control at the Department of the Treasury, tel. (202) 622-0077 (ask for Document #1900). The document also is available at the Department of Treasury web site.

Colombia is the United States' fifth-largest export market in Latin America—behind Mexico, Brazil, Venezuela, and Argentina—and the 26th-largest market for U.S. products worldwide. The United States is Colombia's principal trading partner, with two-way trade from November 1999 through November 2000 exceeding $9.5 billion--$3.5 billion U.S. exports and $6.0 billion U.S. imports. Colombia benefits from duty-free entry—for a 10-year period, through 2001—for certain of its exports to the United States under the Andean Trade Preferences Act. Colombia improved protection of intellectual property rights through the adoption of three Andean Pact decisions in 1993 and 1994, but the U.S. remains concerned over deficiencies in licensing, patent regulations, and copyright protection.

Colombia is also the largest export partner of the Dutch constituent country of Aruba (39.4%).[7]

The petroleum and natural gas coal mining, chemical, and manufacturing industries attract the greatest U.S. investment interest. U.S. investment accounted for 37.8% ($4.2 billion) of the total $11.2 billion in foreign direct investment at the end of 1997, excluding petroleum and portfolio investment. Worker rights and benefits in the U.S.-dominated sectors are more favorable than general working conditions. Examples include shorter-than-average working hours, higher wages, and compliance with health and safety standards above the national average.

Tertiary industries

The services sector dominates Colombia's GDP, contributing 58 percent of GDP in 2007, and, given worldwide trends, its dominance will probably continue. The sector is characterized by its heterogeneity, being the largest for employment (61 percent), in both the formal and informal sectors.[41]

Arts and music

Since the early 2010s, the Colombian government has shown interest in exporting modern Colombian pop culture to the world (which includes video games, music, movies, TV shows, fashion, cosmetics, and food) as a way of diversifying the economy and changing the image of Colombia. In the Hispanic world, Colombia is only behind Mexico in cultural exports at US$750 million annually, and is already a regional leader in cosmetic and beauty exports.[24]

Travel and tourism

Tourism in Colombia is an important sector in the country's economy. Colombia has major attractions as a tourist destination, such as Cartagena and its historic surroundings, which are on the UNESCO World Heritage List; the insular department of San Andrés, Providencia y Santa Catalina; Santa Marta, Cartagena and the surrounding area. Fairly recently, Bogotá, the nation's capital, has become Colombia's major tourist destination because of its improved museums and entertainment facilities and its major urban renovations, including the rehabilitation of public areas, the development of parks, and the creation of an extensive network of cycling routes. With its very rich and varied geography, which includes the Amazon and Andean regions, the llanos, the Caribbean and Pacific coasts, and the deserts of La Guajira, and its unique biodiversity, Colombia also has major potential for ecotourism.[47]

The direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP in 2013 was COP11,974.3mn (1.7% of GDP). This is forecast to rise by 7.4% to COP12,863.4mn in 2014. This primarily reflects the economic activity generated by industries such as hotels, travel agents, airlines and other passenger transportation services (excluding commuter services). But it also includes, for example, the activities of the restaurant and leisure industries directly supported by tourists.[48] The direct contribution of Travel & Tourism to GDP is expected to grow by 4.1% pa to COP19,208.4mn (1.8% of GDP) by 2024.

Eco-tourism

Eco-tourism is very promising in Colombia. Colombia has vast coastlines, mountainous areas, and tropical jungles. There are volcanoes and waterfalls as well. This makes Colombia a biodiverse country with many attractions for foreign visitors.

The Colombian coffee growing axis (Spanish: Eje Cafetero), also known as the Coffee Triangle (Spanish: Triángulo del Café), is a part of the Colombian Paisa region in the rural area of Colombia, which is famous for growing and production of a majority of Colombian coffee, considered by some as the best coffee in the world. There are three departments in the area: Caldas, Quindío and Risaralda. These departments are among the smallest departments in Colombia with a total combined area of 13873 km2 (5356 mi2), about 1.2% of the Colombian territory. The combined population is 2,291,195 (2005 census).[49]

Transportation and telecommunications

Colombia's geography, with three cordilleras of the Andes running up the country from south to north, and jungle in the Amazon and Darién regions, represents a major obstacle to the development of national road networks with international connections. Thus, the basic nature of the country's transportation infrastructure is not surprising. In the spirit of the 1991 constitution, in 1993 the Ministry of Public Works and Transportation was reorganized and renamed the Ministry of Transportation. In 2000 the new ministry strengthened its role as the planner and regulator within the sector.[50]

Air transportation

Colombia was a pioneer in promoting airlines in an effort to overcome its geographic barriers to transportation. The Colombian Company of Air Navigation, formed in 1919, was the second commercial airline in the world. It was not until the 1940s that Colombia's air transportation began growing significantly in the number of companies, passengers carried, and kilometers covered. In the early 2000s, an average of 72 percent of the passengers transported by air go to national destinations, while 28 percent travel internationally. One notable feature is that after the reforms of the beginning of the 1990s, the number of international passengers tripled by 2003. In 1993 the construction, administration, operation, and maintenance of the main airports transferred to departmental authorities and the private sector, including companies specializing in air transportation. Within this process, in 2006 the International Airport Operator (Opain), a Swiss-Colombian consortium, won the concession to manage and develop Bogotá's El Dorado International Airport. El Dorado is the largest airport in Latin America in terms of cargo traffic (33rd worldwide), with 622,145 metric tons in 2013, second in terms of traffic movements (45th worldwide) and third in terms of passengers (50th among the busiest airports in the world). In addition to El Dorado, Colombia's international airports are Palo Negro in Bucaramanga, Simón Bolívar in Santa Marta, Cortissoz in Barranquilla, Rafael Núñez in Cartagena, José María Córdova in Rionegro near Medellín, Alfonso Bonilla Aragón in Cali, Alfredo Vásquez Cobo in Leticia, Matecaña in Pereira, Gustavo Rojas Pinilla in San Andrés, and Camilo Daza in Cúcuta. In 2006 Colombia was generally reported to have a total of 984 airports, of which 103 had paved runways and 883 were unpaved. The Ministry of Transportation listed 581 airports in 2007, but it may have used a different methodology for counting them.[50]

Poverty and inequality

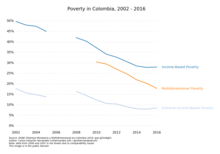

After a large crisis in 1999, poverty in Colombia has had a decreasing trend. The share of Colombians below the income-based poverty line fell from 50% in 2002 to 28% in 2016. The share of Colombians below the extreme income-based poverty line fell from 18% to 9% in the same period. Multidimensional poverty fell from 30% to 18% between 2010 and 2016.[33] [51]

Colombia has a Gini coefficient of 51.7.[52]

See also

- Taxation in Colombia

- WWB Colombia

- Economic history of Colombia

- List of companies of Colombia

- Colombia and the World Bank

- Economy of South America

- List of Colombian departments by GDP

- List of Latin American and Caribbean countries by GDP growth

- List of Latin American and Caribbean countries by GDP (nominal)

- List of Latin American and Caribbean countries by GDP (PPP)

References

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "World Bank Country and Lending Groups". datahelpdesk.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- "Population, total". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 17 August 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 21 October 2019.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2020". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Global Economic Prospects, June 2020". openknowledge.worldbank.org. World Bank. p. 86. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- "The World Factbook". CIA.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at national poverty lines (% of population)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Poverty headcount ratio at $5.50 a day (2011 PPP) (% of population) - Colombia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Poverty and inequality". Retrieved 15 December 2019.

- "Human Development Index (HDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Inequality-adjusted Human Development Index (IHDI)". hdr.undp.org. HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 11 December 2019.

- "Labor force, total - Colombia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (%) (national estimate) - Colombia". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- "Unemployment rate". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Youth unemployment rate". data.oecd.org. OECD. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Ease of Doing Business in Colombia". Doingbusiness.org. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- "Sovereigns rating list". Standard & Poor's. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- "World Economic Outlook Database, April 2019". IMF.org. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Azteca Installs 12,000 km of Fiber Optic Cable in Colombia". AZO Optica. 9 July 2013.

- "Colombian Economy Grows 6.4 Percent, Follows China As Fastest Growing Country". Curaçao Online. 22 July 2014.

- "Passing the baton". The Economist. 2 August 2014.

- "Inicio". www.procolombia.co (in Spanish). 28 March 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Colombia exporta US$748 millones en bienes culturales". El Tiempo. 17 April 2011.

- "Colombia received 12% more foreign visitors in 2014: Govt". Colombia Reports. 18 February 2015.

- "Colombia superó la meta de 4 millones de turistas extranjeros en 2014". Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism. 17 February 2015. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Plan Colombia: Colombia: Peace Agreements: Library and Links: U.S. Institute of Peace Archived 24 November 2004 at the Wayback Machine

- "GDP growth (annual %)". data.worldbank.org. World Bank. Retrieved 19 July 2019.

- "Overview". World Bank. Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- El Tiempo, Casa Editorial (28 March 2015). "¿Qué hay detrás de la rápida disminución de la pobreza en Colombia?". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Report for Selected Countries and Subjects". Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- "NACIONALES TRIMESTRALES -PIB- Composición del PIB Colombiano por demanda y Composición del PIB Colombiano Oferta" (in Spanish). dane.gov.co. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 29 September 2015.

- goo.gl/Vs8gki

- El Tiempo, Casa Editorial (8 June 2020). "Los pasos que dará la reforma laboral que iniciará el país". El Tiempo (in Spanish). Retrieved 10 June 2020.

- "Acquisition of Imusa : conclusive steps". Groupe SEB. December 2010.

- "Consumer Appliances in Colombia". Euromonitor International. January 2015.

- "Colombia Launches IT Push To Grow Country's Technology Sector Internationally". CRN. 24 July 2014.

- "Todo listo para masificación de televisores tecnología 4K en Colombia". El Tiempo. 27 January 2015.

- "Compre Colombiano". Ministry of Commerce, Industry, and Tourism.

- "Ambitious plans to transform Colombia". Financial Times. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- Roberto Steiner and Hernán Vallejo. "The Economy". In Colombia: A Country Study (Rex A. Hudson, ed.). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (2010).

- "BOST project". UNCO United Refineries. Retrieved 8 June 2008.

- "The Dirty Story Behind Local Energy", The Boston Phoenix, 1 October 2007.

- Unidad de Planeación Minero Energética – UPME (2004), Boletín Estadístico de Minas y Energía 1994–2004. PDF file in Spanish.

- World Coal Institute (2004), Coal Facts – 2004 Edition. PDF file Archived 16 January 2006 at the Wayback Machine.

- Posada-Carbo, Eduardo (1998). Colombia: The Politics of Reforming the State. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 194–195. ISBN 978-0-312-17618-1.

- Roberto Steiner and Hernán Vallejo. "Tourism". In Colombia: A Country Study (Rex A. Hudson, ed.). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (2010)

- World Travel and Tourism Council. Travel and Tourism Economic Impact 2014: Colombia

- Colombia Official Travel Guide

- Roberto Steiner and Hernán Vallejo (2010). Rex A. Hudson (ed.). "Colombia: A Country Study" (PDF). Library of Congress Federal Research Division. pp. 181–4.

- DANE (Pobreza Monetaria y Multidimensional en Colombia 2016: goo.gl/Vs8gki)

- "EMnet event "Colombia and the OECD: collaborating for competitiveness" - OECD". www.oecd.org. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- data cover general government debt, and includes debt instruments issued (or owned) by government entities other than the treasury; the data include treasury debt held by foreign entities; the data include debt issued by subnational entities