Military budget

A military budget (or military expenditure), also known as a defense budget, is the amount of financial resources dedicated by a state to raising and maintaining an armed forces or other methods essential for defense purposes.

Standard, a military defense budget is based on internal surplus production with merely 1% of the internal population in service, at a cost effectiveness equating to internal social security (Farmers feed their own). Expertice is either internal or/and hired at a rating where each of the men or woman hiring those services expends a part of their individual budget to maintain those hired, including social security for direct family members of those hired (feedback equation).

Example: Total Population: 350 million Social Security: 1 adult 1 dependent (1A1D) 17 per hour, 8 hrs, 3 months. Workable hours: 2087 per annum.

350 million / 2 (half total population) × 1% × 2087/4 × 17 = Total blind real budget, half on family, half on men, of which the men obtain half for themselves and half for equipment and supplies.

Total: Approximately 8 billion Total.

Everything else has to be amortized over longer periods but must come from that same 8 billion/annum.

Financing militaries

Military budgets often reflect how strongly a country perceives the likelihood of threats against it, or the amount of aggression it wishes to conjure. It also gives an idea of how much financing should be provided for the upcoming fiscal year. The size of a budget also reflects the country's ability to fund military activities.[2] Factors include the size of that country's economy, other financial demands on that entity, and the willingness of that entity's government or people to fund such military activity. Generally excluded from military expenditures is spending on internal law enforcement and disabled veteran rehabilitation. The effects of military expenditure on a nation's economy and society, and what determines military expenditure, are notable issues in political science and economics. There are controversial findings and theories regarding these topics. Generally, some suggest military expenditure is a boost to local economies.[3] Still, others maintain military expenditure is a drag on development.[4]

Every year in April is the Global Day of Action on Military Spending (GDAMS), which aims to gather people and create a global movement that persuades governments to reallocate their military spending to essential human needs such as food, education, health care, social services and environmental concerns.[5]

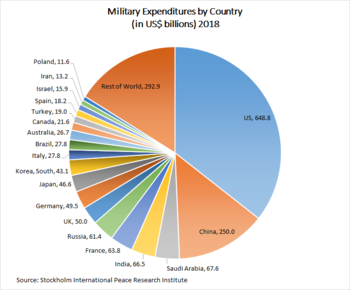

Among the countries maintaining some of the world's largest military budgets, China, India, France, Germany, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States are frequently recognized to be great powers.[6]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in 2018, total world military expenditure amounted to 1822 billion US$.[7]

In 2018, the United States spent 3.2% of its GDP on its military, while China 1.9%, Russia 3.9%, France 2.3%, United Kingdom 1.8%, India 2.4%, Israel 4.3%, South Korea 2.6% and Germany spent 1.2% of its GDP on defense.[1][8]

Historic expenditure

The Saturday Review magazine in February 1898 outlined the levels of military expenditure as a percentage of tax revenue spent by the then great powers for the year 1897:[9]

- United States: 17%. The United States has fluctuated for decades, depending on the conflict of the time. The first spike in defense spending, and in turn taxes, came during the very beginning of the 19th century.[10] During World War I, the United States spent 22% of Gross Domestic Product, while during peacetime, the government spent on as little as 1% Gross Domestic Product (GDP).[11] This changed following World War II as the United States government were experiencing an immense fear of the expansion of Communism and therefore heightened security on all fronts. This was supported by Americans as it brought upon them a sense of security and the 3.6% GDP they were contributing to was a large decrease from the whopping amounts of capital being spent during WWII that exceeded 41%, before decreasing to 10% during the Cold War and for about two more decades after, including the Vietnam War, before beginning to decrease in the 1970s down to 6%, then 5.5% in 1979 before beginning to steadily incline once again.[11][10] After 2001, though, and the September 11 terrorist attacks, defense spending spiked again, peaking at 5.7% in 2010.[11]

- Russian Empire: 21%

- French Third Republic: 27%

- British Empire: 39%

- German Empire: 43%

- Empire of Japan: 55%

In 1983, during the Reagan administration, Employment Research Associates, a non-profit economic consulting firm based in Lansing, Michigan, found that military spending not only produces far fewer jobs per dollar invested, it siphons off intellectual and scientific expertise needed to advance society.[12]

See also

- List of countries by military expenditures

- List of countries by past military expenditure

- List of countries by military expenditure per capita

- Permanent war economy

- History of military technology

- Military Keynesianism

- Military–industrial complex

- Peace dividend

- Defense contractor

- Guns versus butter model

- List of countries by Global Militarization Index

References

- 2018 data from: "Military expenditure (% of GDP). SIPRI Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament and International Security". World Bank. Retrieved 2019-03-08.

- Statistics on Defense Expenditures in the U.S. per Capita, 1990-2011, NATO, April 2012.

- Hicks, Louis; Curt Raney (2003). "The Social Impact of Military Growth in St. Mary's County, Maryland, 1940-1995". Armed Forces & Society. 29 (3): 353–371. doi:10.1177/0095327x0302900303.

- Nef, J.U. (1950). War and Human Progress. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- "Global Campaign on Military Spending - Cut Military Spending - Fund Human Needs". Global Campaign on Military Spending. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 18 December 2017.

- Baron, Joshua (22 January 2014). Great Power Peace and American Primacy: The Origins and Future of a New International Order. United States: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1137299482.

- Trends in World Military Expenditure Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

- "The Biggest Military Budgets As A Share Of GDP In 2018 [Infographic]". Forbes. April 29, 2019.

- Frank Harris (editor) (February 1898). Saturday Review Magazine.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Borch, Casey, and Michael Wallace. “Military Spending and Economic Well-Being in the American States: The Post-Vietnam War Era.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 4, 2010, pp. 1727–1752. Oxford University Press, doi: 10.1353/sof.0.0268. Accessed 15 October 2017.

- Chantrill, Christopher. “What Is the Total US Defense Spending?” US Government Defense Spending History with Charts - a Www.usgovernmentspending.com Briefing, American Thinkers, 17 July 2011, www.usgovernmentspending.com/defense_spending

- https://indypendent.org/2020/04/bombers-not-ventilators-the-high-price-of-u-s-militarism-comes-due/

External links

- Hicks, Louis; Raney, Curt. "The Social Impact of Military Growth in St. Mary's County, Maryland, 1940-1995". Armed Forces & Society. 29: 3.