Vatteluttu

Vatteluttu (Tamil: வட்டெழுத்து, Vaṭṭeḻuttu; Malayalam: വട്ടെഴുത്ത്, Vaṭṭeḻuttŭ; Mozhi: Vattezhuthu) was an abugida of South India (Tamil Nadu and Kerala) and Sri Lanka used for writing the Tamil and Malayalam languages.[2][4]

| Vatteluttu | |

|---|---|

_(early_11th_century_AD).jpg) Vatteluttu from Kerala (11th century AD) (Malayalam) (Jewish copper plates of Cochin) | |

| Type | |

| Languages | |

Parent systems | Proto-Sinaitic alphabet[a] |

Sister systems | |

[a] The Semitic origin of the Brahmic scripts is not universally agreed upon. | |

The earliest forms of Vatteluttu have been traced to memorial stone inscriptions from the 4th century AD.[1] It probably developed from Tamil Brahmi around 4th-5th century AD.[1][5][6] Vatteluttu is distinctly attested in a number of inscriptions in Tamil Nadu from the 6th century AD.[2]

Vatteluttu characters are marked by a more cursive appearance than the modern Tamil script.[2] The script is written left to right, as is typical for Indian scripts.[2] Like the Tamil script from the 11th and later centuries, the script omits the virama V muting device.[2]

Vatteluttu was the common script for writing Tamil in the Tamil Nadu and Kerala till c. 9th century AD.[3] The modern Tamil script displaced Vatteluttu as the principle script for writing Tamil in c. 9th-10th century AD.[1][3] Vatteluttu use is also attested in north-eastern Sri Lankan rock inscriptions, such as those found near Trincomalee, dated c. 5th and 8th centuries AD.[7]

Etymology

Three possible hypotheses for the etymology of the term 'Vatteluttu' are commonly accepted. Eluttu/ezhuthu is lit. 'written form' in this context; and affixed here it means 'writing system' or 'script'. The three hypothesised meanings for the name are:

Vatteluttu in Kerala

In what is now Kerala, Vatteluttu continued for a much longer period than in Tamil Nadu (by incorporating characters from Grantha/Southern Pallava Grantha script to represent Indo-Aryan or Sanskrit words in early Malayalam).[8][3]

Early Malayalam inscriptions related to the Chera Perumals, kings of Kerala between c. 9th and 12th century AD, are composed mostly in Vatteluttu.[3][9] The script went on evolving during this period (in such a way that the date of a record may be fixed approximately by reference to the script alone) and in the post-Chera Perumal period (c. 12th century onwards).[3]

The political importance of the use of a uniform script (Vatteluttu) and language (early forms of Malayalam) has not been adequately recognized at least in the context of the history of Kēraḷa. Script, unless used for purposes of trade, can be one of those engines used by a political agency (the Chera Perumal king) to impose its authority over large areas in pre-modern time when the use of literacy for purposes of communication was limited.

— Veluthat Kesavan (historian), History and Historiography in Constituting a Region: The Case of Kerala (2018)

The modern Malayalam script, a modified form of the Grantha/Southern Pallava Grantha script, gradually replaced Vatteluttu for writing Malayalam in Kerala.[3] It gradually developed into a script known as "Koleluttu" in Kerala (and continued in use among certain Kerala communities, especially Muslims and Christians, even after the 16th century and up to the 19th century AD).[3]

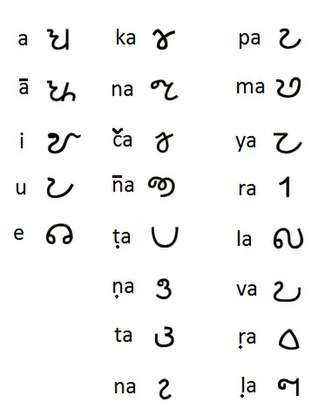

Characters

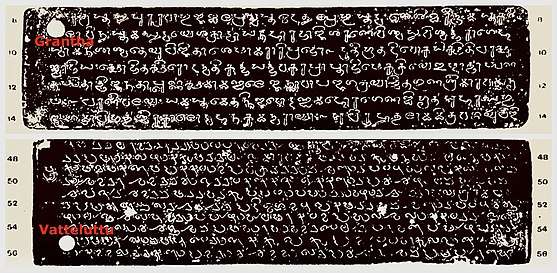

_plate_1.jpg)

Evolution of the Tamil and the Vatteluttu scripts

The image shows the divergent evolution of the Tamil and the Vatteluttu scripts. The Vatteluttu script is shown on the left column, Tamil Brahmi in the middle column, and the Tamil script is shown on the right column. The earlier is near the centre and that later is towards the sides.

See also

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vatteluttu alphabet. |

- K. Rajan (2001). "Territorial Division as Gleaned from Memorial Stones". East and West. 51 (3/4): 359–367. JSTOR 29757518.

- Coulmas, Florian (1999). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Writing Systems. p. 542. ISBN 9780631214816.

- Narayanan, M. G. S. Perumāḷs of Kerala. Thrissur (Kerala): CosmoBooks, 2013. 379-80 and 398.

- "Tamil language | Origin, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-03-04.

- Iravatham Mahadevan (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy. Cre-A. pp. 210–213. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- Richard Salomon (2004), Review: Early Tamil Epigraphy: From the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. By IRAVATHAM MAHADEVAN. Harvard Oriental Series Volume 62, The Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 124, Issue 3, pp. 565-569, doi:10.2307/4132283

- Manogaran. The Untold Story of Ancient Tamils in Sri Lanka. p. 31.

- Bhadriraju Krishnamurti (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-139-43533-8.

- Veluthat, Kesavan. “History and Historiography in Constituting a Region: The Case of Kerala.” Studies in People’s History, vol. 5, no. 1, June 2018, pp. 13–31.