Valley Forge National Historical Park

Valley Forge National Historical Park is the site of the third winter encampment of the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, taking place from December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778. The National Park Service preserves the site and interprets the history of the Valley Forge encampment. Originally Valley Forge State Park, it became a national historical park in 1976. The park contains historical buildings, recreated encampment structures, memorials, museums, and recreation facilities.

Valley Forge National Historical Park | |

U.S. National Historical Park | |

| |

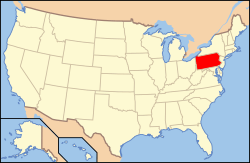

| Location | Montgomery County and Chester County, Pennsylvania, USA |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | King of Prussia, Pennsylvania |

| Coordinates | 40°05′49″N 75°26′20″W |

| Area | 3,466 acres (1,403 ha) |

| Visitation | 1,303,047 (2011)[1] |

| Website | Valley Forge National Historical Park |

| NRHP reference No. | 66000657 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

| Designated NHLD | January 20, 1961 |

| Designated NHP | State Park: 1893 National Historical Park: July 4, 1976 |

The park encompasses 3,500 acres (1,400 ha)[2] and is visited by over 1.2 million people each year. Visitors can see restored historic structures, reconstructed structures such as the iconic log huts, and monuments erected by the states from which the Continental soldiers came. Visitor facilities include a visitor center and museum featuring original artifacts, providing a concise introduction to the American Revolution and the Valley Forge encampment. Ranger programs, tours (walking and trolley), and activities are available seasonally. The park also provides 26 miles (42 km) of hiking and biking trails, which are connected to a robust regional trails system. Wildlife watching, fishing, and boating on the nearby Schuylkill River also are popular.

Historical encampment

From December 19, 1777 to June 19, 1778, the main body of the Continental Army (approximately 12,000 troops) was encamped at Valley Forge. The site was chosen because it was between the seat of the Second Continental Congress in York, supply depots in Reading, and British forces in Philadelphia 18 miles (29 km) away, which fell after the Battle of Brandywine. This was a time of great suffering for the army, but it was also a time of retraining and rejuvenation. The shared hardship of the officers and soldiers of the army, combined with Baron Friedrich von Steuben's professional military training program, are considered key to the subsequent success of the Continental Army and marks a turning point in the Revolutionary War.

Park history

Valley Forge was established as the first state park of Pennsylvania in 1893 by the Valley Forge Park Commission (VFPC) "to preserve, improve, and maintain as a public park the site on which General George Washington's army encamped at Valley Forge.".[3] The area around Washington's Headquarters was chosen as the park site. In 1923, the VFPC was brought under the Department of Forests and Waters and later incorporated into the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission in 1971.[3]

The park served as the location of the National Scout Jamboree in 1950, 1957, and 1964.

Valley Forge was designated a U.S. National Historic Landmark in 1961 and was listed in the initial National Register of Historic Places in 1966.[4][5] The area covered by these listings goes outside what was the Valley Forge State Park boundaries to include four historic houses where the Marquis de Lafayette and other officers were quartered.[5]:6

In 1976, Pennsylvania gave the park as a gift to the nation for the Bicentennial. The U.S. Congress passed a law signed by President Gerald Ford on July 4, 1976, authorizing the addition of Valley Forge National Historical Park as the 283rd Unit of the National Park System.[6] In addition to establishing Valley Forge National Park, the law also allocated an initial budget of $8,622,000 and an additional $500,000 for essential facilities.[7]

Park Superintendents

State Park Superintendents

- Frederick D. Stone (1893 – 1895)

- Holstein DeHaven (1895 – 1898)

- Charles C. Adams (1899 – 1903)

- A.H. Bowen (1903 – 1911)

- Col. S.S. Hartranft (1911 – 1921)

- John S. Kennedy (1921 – 1924)

- Jerome J. Sheas (1925 – 1935)

- Gilbert S. Jones (1935 – 1938)

- Joseph E. Stott (1938 – 1940)

- E.F. Brouse (1940 – 1941)

- L. Ralph Phillips (1941 – 1953)

- Paul E. Felton (1953 – 1955)

- George F. Kenworthy (1955 – 1957)

- Wilford P. Moll (1957 – 1958)

- E.C. Pyle (1958 – 1966)

- Wilford P. Moll (1966 – 1969)

- Charles C. Frost, Jr. (1969 – 1971)

- Horace Wilcox (1971 – 1976)[8]

Regional Affiliation

Upon its designation as a National Park in 1976, Valley Forge considered a part of the Mid-Atlantic Region of the National Park Service. The Mid-Atlantic Region included five states: Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia. This changed in 1995 when the North Atlantic Region merged with the Mid-Atlantic Region to create the Northeast Region. [14]

Features and facilities

Visitor center

The park features a visitor center, which acts as orientation for visitors to the site. The features of the center include a museum with artifacts found during excavations of the park, an interactive muster roll of Continental soldiers encamped at Valley Forge, ranger-led gallery programs and walks, a storytelling program, a photo gallery, a visitor information desk, and a store for books and souvenirs. 90-minute trolley tours of the park and bike rentals are available seasonally from this location. A short 18-minute film, "Valley Forge: A Winter Encampment" is shown in the park's theater next door. The visitor center, built in 1976, is currently undergoing renovation, and visitor center operations have moved to a temporary visitor center, located in the parking lot of the existing facility. The newly remodeled Visitor Center is expected to reopen in late spring 2020.

Headquarters buildings

A key attraction of the park is the restored colonial home used by General George Washington as his headquarters during the encampment. Rehabilitation of the headquarters area was completed in summer 2009, and included the restoration of the old Valley Forge train station into an information center, new guided tours, new exhibits throughout the landscape, and the elimination of several acres of modern paving and restoration of the historic landscape. Quarters of other Continental Army generals are also in the park, including those of Huntington, Varnum, Lord Stirling, Lafayette, and Knox. Varnum's quarters is open on weekends during the summer.

Reconstructed works and buildings

Throughout the park there are reconstructed log cabins of the type thought to be used during the encampment. Earthworks for the defense of the encampment are visible, including four redoubts, the ditch for the Inner Line Defenses, and a reconstructed abatis. The original redoubts and several redans on Route 23, Outer Line Drive, and Inner Line Drive were covered with sod to preserve them, but they are currently in need of further restoration. The original forges, located on Valley Creek, were burned by the British three months prior to Washington's occupation of the park area. However, neither the Upper Forge site nor the Lower Forge site has been reconstructed. There are also several historical buildings that have not been made open to the public because of reasons such as their current state of disrepair. These include: Lord Stirling's Quarters, Knox's Quarters, and the Von Steuben Memorial. Other historical buildings include the P.C. Knox Estate, Kennedy-Supplee Mansion and Potts' Barn.

Washington Memorial Chapel

The Washington Memorial Chapel and National Patriots Bell Tower carillon sit atop a hill at the center of the present park. The chapel is the legacy of Rev. Dr. W. Herbert Burk. Inspired by Burk's 1903 sermon on Washington's birthday, the chapel is a functioning Episcopal Church, built as a tribute to Washington. Burk was also instrumental in the development of the park, including obtaining Washington's campaign tent and banner, which used to be on display in the visitor center but is now in the Museum of the American Revolution in Philadelphia.[15] The chapel and attached bell tower are not technically part of the park but serve the spiritual needs of the park and the community that surround it. The bell tower houses the Daughters of the American Revolution Patriot Rolls, listing those that served in the Revolutionary War, and the chapel grounds hosted the World of Scouting Museum.[16]

Memorial markers

Sitting atop a hill at the intersection of the Outer Line of Defense with the Gulph Road, the National Memorial Arch dominates the southern portion of the park. It is dedicated "to the officers and private soldiers of the Continental Army December 19, 1777 – June 19, 1778." The arch was commissioned by an act of the 61st Congress in 1910 and completed in 1917. It is inscribed with George Washington's tribute to the perseverance and endurance of his army:

Naked and Starving as they are>

We cannot enough admire

the Incomparable Patience and Fidelity

of the Soldiery.

The drive is lined with large (~2 m high) memorial stones for each of the brigades, or "lines", that encamped there. Crossing Gulph Road at the arch, the drive proceeds through the Pennsylvania Columns and past the hilltop statue of Anthony Wayne on horse. More brigade stones line Port Kennedy Road.

Mount Joy Observation Tower

Atop Mount Joy, the highest elevation in the main park area, stood a steel observation tower. The tower was closed in the 1980s because of deterioration, liability concerns, and the surrounding trees outgrowing the platform. The tower was removed and shipped to a private area near Wellsboro, Pennsylvania, where people can still climb it. The area where it stood is now only accessible by foot trail, the roads have been removed and the area is being given back to the woods.

Trails

There are 26 miles (42 km) of hiking and biking trails within the park, such as the Valley Creek Trail and the River Trail. The main trail is the Joseph Plumb Martin Trail, which encircles 8.7 miles of the park. Portions of regional trails, including the Horse Shoe Trail and the Schuylkill River Trail, also run through the park.

Recreation

The many trails in Valley Forge allow for different activities such as jogging, walking and biking. Other activities include horseback riding and canoeing/kayaking. There are three picnic areas located on the site. In addition, Park Rangers dressed in period uniforms are stationed as the Muhlenburg Brigade Huts and Washington's Headquarters, ready to inform visitors about the historic events that happened on the site. The Valley Forge 5-Mile Revolutionary Run is also held in the park every April.

Train station

Near Washington's Headquarters is the Valley Forge Train Station, owned by the park. The station was completed in 1911 by the Reading Railroad and was the point of entry to the park for travelers who came by rail through the 1950s from Philadelphia, 23.7 miles (38.1 km) distant.[17] The station was restored in 2009 and is used as a museum and information center that offers visitors a better understanding of Washington's Headquarters and the village of Valley Forge.[18] Constructed of the same type of stone as Washington's Headquarters, the building was erected on a large man-made embankment overlooking the headquarters site.

Near the visitor center is another station at Port Kennedy, on the same line. Also owned by the park, the station, both platforms and the former parking area are in a state of disrepair.[19] Should the long-planned Schuylkill Valley Metro project come to fruition, this station could again connect the park to center city Philadelphia, Pottstown, and Reading with public transportation.

Modern problems

As a park in an increasingly urbanized area, Valley Forge faces problems including traffic, urban sprawl, and an overpopulation of white-tailed deer.

Valley Forge Park Road (PA Route 23), a heavily traveled two-lane commuter road, passes through the park and carries about six million vehicles per year of mostly commuter traffic. Efforts to divert the traffic have thus far been unsuccessful, owing to existing traffic volume on alternate routes. A consortium of local governments and state and federal agencies are working on approaches to traffic congestion throughout the area, particularly improvements to US 422.

In 2001, a privately held 62-acre (25 ha) tract of land within the authorized park boundaries was offered for sale. When the Park Service was unable to purchase it, it was sold to Toll Brothers, a real estate development company, for $2.5 million. It took a grass roots campaign to get the Federal Government to purchase the land from the developer two years later, for $7.5 million.[20]

In 2007, a non-profit organization – the American Revolution Center – purchased 78 acres (32 ha) of land within the park boundary with plans to construct a conference center, hotel, retail, campground and museum on the site.[21] The National Parks Conservation Association and local citizens sued Lower Providence Township over the zoning change that enabled this proposal.[22] The two parties agreed to allow NPS to keep the land, and in exchange, the American Revolution Center was given property in Philadelphia, where it built the Museum of the American Revolution.

An overpopulation of white-tailed deer has resulted in "changes in the species composition, abundance, and distribution of native plant communities and associated wildlife" in the park. In 2008, the National Park Service released a draft deer management plan and environmental impact statement for public review. The intent of the controversial plan was to "support long-term protection, preservation, and restoration of native vegetation and other natural resources within the park."[23] Hunting is expressly prohibited by the legislation that created the park, and action by Congress would be required before it could be sanctioned.[24] Since the plan was put into place, natural habitats have been restored and vegetation not seen in the park for decades has begun to return.

The park includes the site of the Ehret Magnesia Company, a former manufacturer of asbestos-insulated pipes. Pre-existing dolomite quarries were subsequently backfilled with asbestos-containing slurry waste materials. Those areas of the park are closed to visitors, and an effort is underway at permanent remediation.

See also

- Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Pennsylvania

References

- "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-10-06.

- "National Park Service". Retrieved 2019-12-28.

- "Records of the Valley Forge Park Commission (VFPC)". Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- "Valley Forge". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Retrieved 2010-01-13.

- Richard Greenwood (November 5, 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Valley Forge State Park / Valley Forge". National Park Service. and Accompanying six photos, from 1972 and undated

- Valley Forge National Historical Park - Washington Memorial Chapel (U.S. National Park Service)

- Schulze, Richard T. (1976-07-04). "All Info - H.R.5621 - 94th Congress (1975-1976): A bill to authorize the Secretary of the Interior to establish the Valley Forge National Historical Park in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and for other purposes". www.congress.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- http://npshistory.com/publications/vafo/adhi.pdf

- "National Park Service: Historic Listings of NPS Officials (Superintendents of National Park System Areas)". npshistory.com. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- Smith, Jason. "Valley Forge introduces new superintendent". The Phoenix, Reporter & Item. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "Kate Hammond named Superintendent of Valley Forge National Historical Park - Valley Forge National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "Steven Sims Chosen as Superintendent of Valley Forge National Historical Park, Hopewell Furnace National Historic Site - Valley Forge National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "Rose Fennell Named Superintendent - Valley Forge National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2020-07-14.

- Press, The Associated (1995-02-22). "National Park Service to Merge 2 Regions in East". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-04-28.

- "CHAPTER FIVE: The Churches at Valley Forge". Valley Forge National Historic Park. Archived from the original on 2007-03-23. Retrieved 2006-10-30.

- World of Scouting Museum

- Official Guide of the Railways. New York: National Railway Publication Co., February, 1956.

- Petersen, Nancy (January 3, 2007). "A new view of Valley Forge". The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- Train Station

- "Toll Bros: History, Land ... and Battles". Archived from the original on 2007-10-08. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

- http://www.philly.com/inquirer/opinion/pa/20080215_Keep_Valley_Forge_sacred.html

- "Park Advocates Sue Lower Providence Township in Federal Court to Deny Valley Forge Rezoning". National Parks Conservation Association. 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2010-06-14.

- "White-tailed Deer Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Valley Forge National Historical Park, King of Prussia, PA". Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- "Valley Forge park sets deer hearing". Archived from the original on 2006-10-22. Retrieved 2006-10-27.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Valley Forge. |

- Official website

- Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) No. PA-6186, "Valley Forge National Historical Park"

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. PA-114, "Valley Forge Observation Tower"

- Video showing various parts of the park from 2016