Schuylkill River

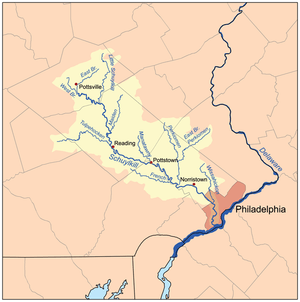

The Schuylkill River (/ˈskuːlkɪl/ SKOOL-kil,[1] locally /ˈskuːkəl/ SKOO-kəl)[2] is a river running northwest to southeast in eastern Pennsylvania, which was improved by navigations into the Schuylkill Canal. Several of its tributaries drain major parts of the center-southern and easternmost Coal Regions in the state.[lower-alpha 1] It flows for 135 miles (217 km)[3] from Pottsville to Philadelphia, where it joins the Delaware River as one of its largest tributaries.

| Schuylkill River | |

|---|---|

The Schuylkill River looking south toward the Philadelphia skyline (2007) | |

The river's watershed drains parts of the western side of Broad Mountain and the ridge-and-valley Appalachians of the southcentral Pennsylvania Coal Region. | |

| Etymology | "hidden/skulking creek" in Dutch |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Pennsylvania |

| Counties | Philadelphia, Montgomery, Chester, Berks, Schuylkill |

| Cities | Philadelphia, Norristown, Pottstown, Reading |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | East Branch Schuylkill River |

| • location | Tuscarora, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, United States |

| • coordinates | 40°46′24″N 76°01′20″W |

| • elevation | 1,540 ft (470 m) |

| 2nd source | West Branch Schuylkill River |

| • location | Minersville, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, United States |

| • coordinates | 40°42′51″N 76°18′46″W |

| • elevation | 1,140 ft (350 m) |

| Source confluence | |

| • location | Schuylkill Haven, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, United States |

| • coordinates | 40°38′01″N 76°10′49″W |

| • elevation | 520 ft (160 m) |

| Mouth | Delaware River |

• location | Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States |

• coordinates | 39°53′04″N 75°11′41″W |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 135 mi (217 km) |

| Basin size | 2,000 sq mi (5,200 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Philadelphia |

| • average | 4,650 cu ft/s (132 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 995 cu ft/s (28.2 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 40,300 cu ft/s (1,140 m3/s) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | Berne |

| • average | 1,120 cu ft/s (32 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Little Schuylkill River, Perkiomen Creek |

| • right | Tulpehocken Creek, French Creek |

Schuylkill River |

|---|

In 1682 William Penn chose the left bank of the confluence upon which he founded the planned city of Philadelphia on lands purchased from the native Delaware nation. It is a designated Pennsylvania Scenic River, and its whole length was once part of the Delaware people's southern territories.

The river's watershed of about 2,000 sq mi (5,180 km2) lies entirely within the state of Pennsylvania, the upper portions in the Ridge-and-valley Appalachian Mountains where the folding of the mountain ridges metamorphically modified bituminous into widespread anthracite deposits located north of the Blue Mountain barrier ridge.

Originating from waters in the Anthracite Coal Region, millions of tons of coal flowed into Philadelphia, once America's largest city, to feed the iron and steel industry.

The source of its eastern branch is in lands now heavily mined situated one ridgeline south of Tuscarora Lake along a drainage divide from the Little Schuylkill about a mile east of the village of Tuscarora and about a mile west of Tamaqua, at Tuscarora Springs in Schuylkill County. Tuscarora Lake is one source of the Little Schuylkill River tributary.

The West Branch starts near Minersville and joins the eastern branch at the town of Schuylkill Haven. It then combines with the Little Schuylkill River downstream in the town of Port Clinton. The Tulpehocken Creek joins it at the western edge of Reading. Wissahickon Creek joins it in northwest Philadelphia. Other major tributaries include: Maiden Creek, Manatawny Creek, French Creek, and Perkiomen Creek.

The Schuylkill joins the Delaware at the site of the former Philadelphia Navy Yard, now the Philadelphia Naval Business Center, just northeast of Philadelphia International Airport.

Major towns

- Pottsville

- Reading

- Pottstown

- Phoenixville

- Norristown

- Conshohocken

- Philadelphia

Name

The Leni Lenape (called Delaware Indians by European settlers) were the original inhabitants of the area around this river. It remains unclear whether these people had a single name for this river. There is evidence that the Lenape called the river Ganshowahanna (which means falling or roaring waters[4]). There is also some belief that the Lenape called the river Tool-pay Hanna (Turtle River) or Tool-pay Hok Ing (Turtle Place).[5] There is a tributary named Tulpehocken near Reading, PA.

The first European explorers of the river were from the Netherlands, Sweden, and then England. It was through historical documents called various names, including Manayunk, Manajungh, Manaiunk,[6] and Lenni Bikbi. The Swedish explorer called it Menejackse kill or alternately Skiar kill or the Linde River.[7][8] The (then believed) headwaters of the river, up near Reading, was later called "Tulpehocken" by the English.[9]

The river was called the Dutch name Schuylkill (pronounced [ˈsxœy̯lkɪl]). As kil means "creek" (e.g. Dordtsche Kil) and schuylen (now spelled schuilen) means "to hide, skulk" or "to take refuge, shelter",[10] one explanation given for this name is that it translates to "hidden river", "skulking river" or "sheltered creek"[11] and refers to the river's confluence with the Delaware River at League Island, which was nearly hidden by dense vegetation. This name has traditionally been credited to Arent Corsen (or Arendt Corssen), an agent of the Dutch West India Company who purchased land “on the Schuylkill River” in 1633.[12] Another explanation is that the name properly translates to "hideout creek" in one of the Algonquian languages spoken by a Leni Lenape in their confederation.[lower-alpha 2]

History

The mighty Susquehannock confederation claimed the area along the Schuylkill as a hunting ground, as they did to the lands down along the Chesapeake Bay to the left bank Potomac River, across from the Powhatan Confederacy when traders first stopped in the Delaware and settlers arrived in the first decade of the 1600s.[13] With ample tributary streams, the Schuylkill was ground zero during the early years of the Beaver Wars, during which the Delaware peoples became tributary to the victorious Susquehannocks, an Iroquoian people also often in contention with their relatives,[13] both the Erie people west and northwest through the gaps of the Allegheny in eastern Ohio and northwestern Pennsylvania (between the upper Allegheny River and Lake Erie), and the Five Nations of the Iroquois, another Amerindian confederation eastwards from the right bank of the Genesee River through the Finger Lakes region of upper New York then down the Saint Lawrence.

The Lenape had settlements on the river, including Nittabakonck ("place where heroes reside"), a village on the east bank just south of the confluence of Wissahickon Creek, and the Passyunk site, on the west bank where the Schuylkill meets the Delaware River.[7][14]

Patriot paper maker Frederick Bicking owned a fishery on the river prior to the Revolution, and Thomas Paine tried in vain to interest the citizens in funding an iron bridge over this river, before abandoning "pontifical works" on account of the French Revolution. In the next decades, pioneering industrialists Josiah White and protege & partner Erskine Hazard built iron industries at the Falls of the Schuylkill in Jefferson's administration, where White built a suspension bridge with cables made from their wire mill. During the war of 1812 the two took delivery of an ark of anthracite coal which was notoriously difficult to combust reliably and experimented with ways to use it industrially, providing the knowledge to successfully begin resolving the ongoing decades long energy crises around eastern cities.[15] The two then heavily backed the flagging effort to improve navigation on the Schuylkill, which efforts date back to legislation measures as early as 1762.

Needing energy resources, and by 1816 disenchanted with the lack of urgency found in other investors to accelerate the anemic (underfunded) construction rate of the Schuylkill Canal, the two jumped to option the mining rights of the Lehigh Coal Mine Company, which disenchanted stockholders were giving up on. They then waited until a charter to improve the Lehigh went delinquent, resulting in two groups of investors forming two complementary companies in 1818 that jump-started the industrial revolution: the Lehigh Coal Company and the Lehigh Navigation Company. Following White's bold plan, the latter company improved down river navigation on the Lehigh using his 'Bear Trap Locks' design to deliver over 365 tons of anthracite to Philadelphia docks by December 1820, four years ahead of promises to Stockholders. The success, along with the pending opening of the first operable sections of New York's Erie Canal spurred stockholders of the Schuylkill Canal to finally fund the works. A project which had languished for over a decade got capitalized and began operations in 1822—the same year the Lehigh companies combined into the Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, having had to raise additional funds for repairs due to badly ice-damaged improvements, a common problem with northern canals.

The success of these projects and the rosy promise of anthracite (a new wonder fuel in the day) to alleviate energy problems spurred canal construction for the next decade in the east, and commercial opportunities funded three decades of investment from Illinois to the Atlantic Ocean, including the ambitious 1824 Main Line of Public Works bill to connect Philadelphia with the newly emerging states of the Northwest Territory via the Allegheny & Ohio valleys at Pittsburgh and to Lake Erie— leveraging the wide-ranging branches of the Susquehanna River in the state's center. In the 1830s railway technology and new railroads grew in leaps and bounds, and the Schuylkill Valley was at the heart of these developments, as well as the new Anthracite iron and mining industries. From 1820 to the 1860s Iron works, foundries, manufacturing mills, blast furnaces, rolling mills, rail yards, rail roads, warehouses and train stations sprang up throughout the valley. Tiny farm villages grew into vibrant company towns then transitioned into small cities as a major industry and supporting businesses transformed local economics and populations swelled.

Pollution

Restoration of the river has been funded by money left for that purpose in Benjamin Franklin's will.[16]

The river is known to have been on fire more than once throughout history, for example in November 1892 when the surface film of oil that had leaked from nearby oil works at Point Breeze, Philadelphia, was ignited by a match tossed carelessly from a boat, with fatal results.[17]

Silt and coal dust from upstream industries, particularly coal mining and washing operations in the headwaters, led to extensive silting of the river through the early 20th century. The river was shallow and filled with extensive black silt bars. By the early 20th century, upstream coal operations contributed over 3 million tons of silt annually to the river.[18] In 1948, led by then governor James H. Duff, a massive cleanup effort began. Twenty three impounding basins were excavated along the river, to receive dredged silt. The 1945 Desilting Act helped begin this cleanup task.[19]

The quality of the river has improved much over the past decades. A fish ladder to support shad migration has been constructed at the Manayunk dam. Mayfly hatches (signifying good water quality) now occur yearly along the Montgomery sections of the river.

Transportation and recreation

Transportation

The Schuylkill River valley was an important thoroughfare in the eras of canals and railroads. The river itself, the Schuylkill Canal, the Reading Railroad, and the Pennsylvania Railroad were vital shipping conduits from the second decade of the 19th century through the mid-20th century. The rise of trucking capabilities and state & county development of road and highway networks progressively took increasing amounts of business away from both competing transport industries. By the mid-1930s the canals inflexibility and a geographically limited pool of customers steadily shifting energy usage away from anthracite doomed most eastern canals, so the Lehigh, Delaware and Schuylkill Canals all ceased operations during the Great Depression years. The zooming rise of automobile ownership post-World War II, the development of suburbs, and dispersal of industrial buildings into far flung parks serviced by the government supported highways and new Interstate Highways doomed intercity rail transport; even as Interstate Commerce Committee regulations required railway operating companies to maintain passenger rail services past its economic viability—which costs further imperiled the railroad's profits leading to a widespread collapse of the industry in the 1960s and 1970s.

Rail freight still uses many of the same valley rights-of-way that the 19th-century railroads used. Passenger and commuter rail service is more limited. Today, the old rail bed rights-of-way along the river between Philadelphia and Norristown contain SEPTA's Manayunk/Norristown Line (former Reading Railroad right-of-way) and the Schuylkill River Trail (former Pennsylvania Railroad right-of-way).

There are efforts to extend both rail and trail farther upriver than they currently reach. The Schuylkill River Trail continues upriver from Norristown to Mont Clare, and designers plan to connect it to sections above Pottstown. SEPTA Regional Rail service currently does not go farther upriver than Norristown. Visions of resuming commuter rail service farther up the Schuylkill valley ("Schuylkill Valley Metro") have yet to become reality.

The Schuylkill Expressway (I-76) and the Benjamin Franklin Highway (US 422) follow the course of the river from Philadelphia to Valley Forge to Reading. Above Reading, Pennsylvania Route 61 continues along the main river valley to Schuylkill Haven, then follows the east branch to Pottsville. U.S. Route 209 continues along the east branch of the river to its head in Tuscarora. In Philadelphia, Kelly Drive (formerly East River Drive), and Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive (formerly West River Drive) flank the river.

Recreation

The Schuylkill River is very popular with rowing, dragon boat, and outrigger paddling enthusiasts. The Schuylkill Navy was established on the riverside adjacent to the city of Philadelphia to promote amateur rowing in 1858. The Dad Vail Regatta, an annual rowing competition, is held on the river near Boathouse Row, as is the annual BAYADA Home Health Care Regatta, featuring disabled rowers from all over the continent, and in autumn the annual Head of the Schuylkill Regatta takes place in Philadelphia. Also, the Stotesbury Cup Regatta, the biggest high school regatta in the world, takes place there. The Chinese sport of dragon boat racing was introduced to the United States on the Schuylkill in 1983, and two major dragon boat regattas are held there in June and October of each year.

Water skiing, swimming and other aquatic sports are also common outside of Philadelphia city limits.[20]

The Schuylkill River Trail,[21] which generally follows the river bank, is a multi-use trail for walking, running, bicycling, rollerblading, and other outdoor activities. The trail presently runs from Philadelphia, through Manayunk to the village of Mont Clare, the latter of which are the locations of the last two remaining watered stretches of the Schuylkill Canal. There is also a section of trail starting at Pottstown and running upriver toward Reading. Plans are under way to complete the trail from the Delaware River to Reading.

In popular culture

Television

In the "Thunder Gun Express" episode of It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia, Frank Reynolds (played by Danny DeVito), steals a tourist ferry and travels down the Schuylkill River, noting that it's "the depository of all the unsolved crimes and murders in Philadelphia." Also, in the "Mac Day" episode, Mac (played by Rob McElhenney), declares that part of his "Mac Day" will include the gang filming scenes for his series "Project Badass" over the Schuylkill River with his cousin Country Mac (played by Seann William Scott).

In several episodes of Cold Case one or another of the Cold Case squad mentions finding "a floater in the Schuylkill."

Film

In the 2019 film The Irishman, the Mob hitman Frank Sheeran, played by Robert De Niro, disposes of a gun he just used in a hit by tossing it into the Schuylkill River, noting, "There's a spot in the Schuylkill River everybody uses. If they ever send divers down there, they'd be able to arm a small country."

Music

The Schuylkill River, and adjacent neighborhood of Manayunk, are featured as the setting for Audioslave's "Doesn't Remind Me" music video.

In the music video for "Pain" by The War on Drugs (band), the band can be seen floating down the Schuylkill River while performing on a barge.

Literature

The angler, artist, and author Ron P. Swegman has made the Schuylkill River a focal point of two essay collections, Philadelphia on the Fly and Small Fry: The Lure of the Little. Both books describe the experience of fly fishing along the Philadelphia County stretch of the river in the 21st century.

Beth Kephart published a series of poetic ruminations about the river in Flow: The Life and Times of Philadelphia's Schuylkill River in 2007.

The river plays an important part of Jerry Spinelli's young adult fiction novel Maniac Magee. The titular character's parents died before the main timeline of the story when their commuter train plunged into the Schuylkill, and much of the main story takes place in the fictional town of Two Mills, which is based on Spinelli's home town of Norristown, Pennsylvania, also located on the Schuylkill near Philadelphia.

Jules Verne's novel Robur the Conqueror starts out in Philadelphia on the banks of the Schuylkill River.

The river is also the setting of the fictional estate White Acre in Elizabeth Gilbert's 2013 novel The Signature of All Things. Gilbert chose an actual mansion, the Hamilton house, nestled on the west side of the Schuylkill River in the Woodlands Cemetery, near 40th Street and Woodland Avenue, on which to base White Acre.[22]

See also

- List of cities and towns along the Schuylkill River

- List of crossings of the Schuylkill River

- List of Pennsylvania rivers

- Geography of Pennsylvania

Notes

- The Panther Creek Valley and other tributaries of the Little Schuylkill River thread through the most heavily endowed coal valleys in the southern coal region.

- The bulk of the Unami Lenape tribal group actually lived along the Schuylkill River and the southerly located right bank Delaware lands of Greater Philadelphia. As the namesake of their greater peoples suggests, the Delaware River—which the Lenape called Len-api Hanna or "People-Like-Me River," there were other Delaware living throughout the Delaware basin including the stretch up beyond the Lehigh River into the northeastern Poconos and easterly from Port Jervis to western Long Island and a bit of the lower Hudson Valley, and south and west through all of New Jersey, but not into the state of Delaware — which was occupied by the Nanticoke people into the 1700s.

References

- Oxford Dictionary: definition of Schuylkill River (American English)

- "Definition of SCHUYLKILL". www.merriam-webster.com.

- U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map Archived 2012-04-05 at WebCite, accessed April 1, 2011

- Donnalley, Thomas K., Hand book of tribal names of Pennsylvania, together with signification of Indian words, Philadelphia:Donnalley, (1908), p. 37

- See The Schuylkill Center for Environmental Education

- See for example, Pennypacker, Samuel Whitaker, Annals of Phoenixville and Its Vicinity: From the Settlement to the Year 1871, Giving the Origin etc., Philadelphia:Bavis &Pennypacker, 1872, p.1

- Scharf, Thomas (1884). History of Philadelphia: 1609 - 1834. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts & Co. ISBN 9785883517104.

- Nickels, Thom (June 6, 2001). Manayunk. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9780738505114.

- Pennypacker, Samuel Whitaker (1872). Annals of Phoenixville and Its Vicinity: From the Settlement to the Year 1871. Phoenixville, PA: Bavis & Pennypacker, printers. pp. 5.

- Hexham, Henry; Manly, Daniel (1675). A copious English and Netherdutch Dictionary. Leers. p. 965.

- Oldschool, Oliver (1809). The Portfolio. p. 520.

- Hanna, C.A., The Wilderness Trail, Volume 1, New York:Putnam’s Sons (1911), p. 108

- Editor: Alvin M. Josephy, Jr., by The editors of American Heritage Magazine (1961). pages 180-211, 188-189 (ed.). The American Heritage Book of Indians. American Heritage Publishing Co., Inc. LCCN 61-14871.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Editor: Isaac C. Sutton, Esq. "Notes of Family History: The Anderson, Schofield, Pennypacker, Yocum, Crawford, Sutton, Lane, Richardson, Bevan, Aubrey, Bartholomew, DeHaven, Jermain and Walker Families".CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Bartholomew, Ann M.; Metz, Lance E.; Kneis, Michael (1989). DELAWARE and LEHIGH CANALS, 158 pages (First ed.). Oak Printing Company, Bethlehem, Pennsylvania: Center for Canal History and Technology, Hugh Moore Historical Park and Museum, Inc., Easton, Pennsylvania. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0930973097. LCCN 89-25150.

- "The Last Will and Testament of Benjamin Franklin". Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- "The River Set On Fire – One Life Lost, Two Men Badly Burned, & One Vessel Damaged" (PDF). The New York Times. 1892-11-02. Retrieved 2008-05-31.

- Carl Kelemen (17 Feb 2006). "Feature – Desilting Basin Finds New Life as Wildlife Habitat, Educational Sanctuary". paenvironmentdigest.com. Retrieved 8 Feb 2015.

- Bill Wolf (9 Jul 1949). "They're Cleaning up Pennsylvania's Foulest River" (PDF). The Saturday Evening Post. Retrieved 8 Feb 2015.

- "Water skiing on the Schuylkill for good cause". 6abc Philadelphia. January 2, 2017. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- "The Schuylkill River Trail". Schuylkill River Trail Association. 2009. Retrieved 1 October 2012.

- Crimmins, Peter (October 8, 2013). "Historic Philadelphia mansion leaves imprint on Elizabeth Gilbert's 'Signature of All Things'". NewsWorks. Archived from the original on June 5, 2014. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Schuylkill River. |